Definition

Pigment dispersion refers to the release of pigment granules into the anterior chamber. It results from backward bowing of the peripheral iris (reverse pupillary block) with friction between the iris pigment epithelium and the zonular fibers. Pigment is released into the aqueous and deposits in TM, leading to increased IOP and secondary open-angle glaucoma.

Mostly asymptomatic but may have blurred vision, eye pain, and colored halos around lights after exercise or pupillary dilation. More common in young adult, myopic men (age 20 to 45 years). Usually bilateral, but asymmetric. May have lattice degeneration and increased risk of a retinal detachment.

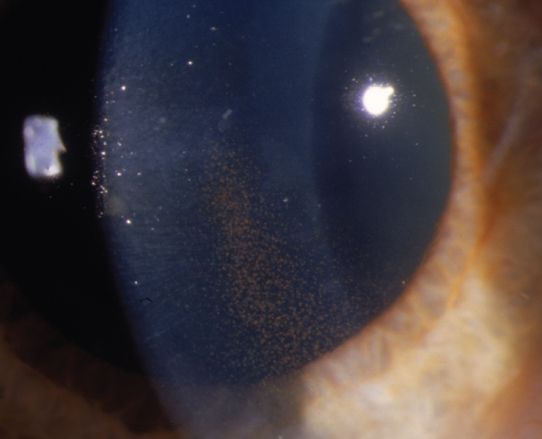

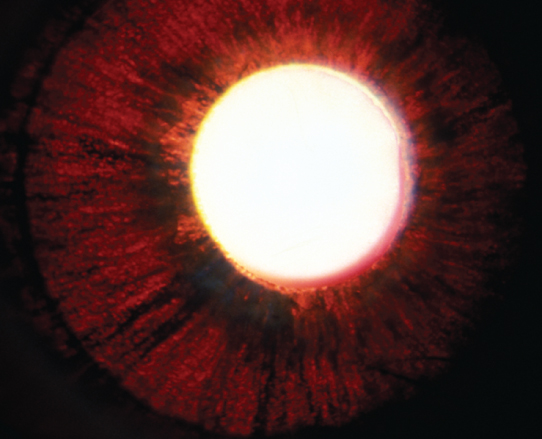

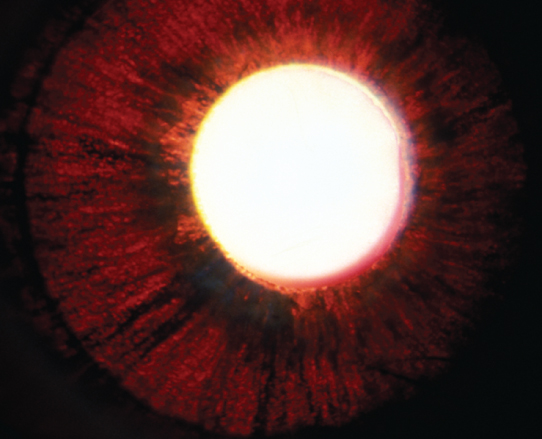

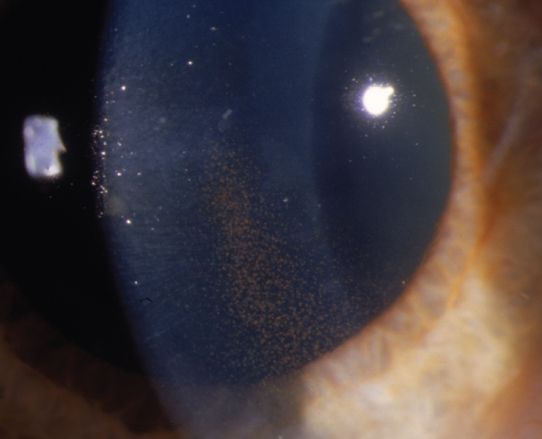

(See Figures 9.9.1 and 9.9.2.)

Figure 9.9.1: Pigment dispersion syndrome with spoke-like iris transillumination defects.

Figure 9.9.2: Pigment dispersion syndrome with a vertical band of endothelial pigment (Krukenberg spindle).

Critical

Midperipheral, spoke-like iris TIDs corresponding to iridozonular contact; open angle with dense pigmentation of the TM for 360 degrees (seen on gonioscopy) in the absence of signs of trauma or inflammation.

Other

A vertical pigment band on the corneal endothelium typically just inferior to the visual axis (Krukenberg spindle); pigment deposition on the posterior zonular-lens attachment line (Zentmayer line or Scheie line), on the anterior hyaloid face, slightly anterior to Schwalbe line (Sampaolesi line), and sometimes on the anterior surface of the iris (which can produce iris heterochromia). The angle often shows a wide ciliary body band with 3+ to 4+ pigmentation of the posterior TM, homogenous for 360 degrees. Pigmentary glaucoma is characterized by pigment dispersion syndrome plus glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Typically, large fluctuations in IOP can occur, during which pigment cells may be seen floating in the anterior chamber.

Similar to POAG. Depends on IOP, optic nerve damage, and symptom extent. Usually, patients with pigment dispersion without ocular hypertension, glaucoma, or symptoms are monitored carefully. A stepwise approach to control IOP is usually taken when glaucomatous optic nerve changes are present. Patients with advanced glaucoma may require multiple medications or filtering surgery for IOP control, similar to POAG. See 9.1, Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma.

Decrease mechanical iridozonular contact. Two methods have been proposed:

Miotic agents: A theoretical first-line therapy because they minimize iridozonular contact. However, because most patients are young and myopic, the resulting fluctuation in myopia may not be tolerated. In addition, approximately 14% of patients have lattice retinal degeneration and are thus predisposed to retinal detachment from the use of miotics. In some cases, pilocarpine 4% gel q.h.s. may be tolerated.

Peripheral laser iridotomy: Laser PI has been recommended to reduce pigment dispersion by decreasing iridozonular contact, but remains controversial. It may be best suited in early-stage disease among symptomatic patients and ill-advised in more advanced stages.

Other antiglaucoma medications. See 9.1, Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma.

SLT or ALT. Due to greater risk of post-laser IOP spikes, lower energy should be used and/or limitation of treatment to 180 degrees per session. Careful post-laser monitoring is needed to detect early IOP rise.

Consider MIGS surgery, guarded filtration procedure, or tube shunt when medical and laser therapies fail. Young myopic patients may be at greater risk for hypotony maculopathy and surgical technique should aim to avoid overfiltration.

Same as POAG. See 9.1, Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma.