Cells and flare in the AC (see Tables 12.1.1 and 12.1.2) and ciliary flush.

Stellate KP—small KP with multiple fine projections from their core, appearing “star-shaped.”

Granulomatous KP—large KP with a greasy or “mutton fat” appearance.

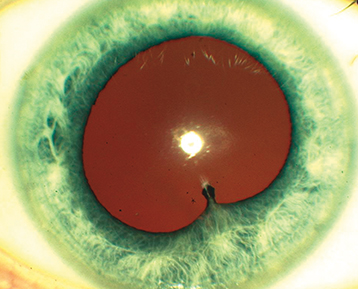

Layering of white blood cells in the AC.

Differential for hypopyon uveitis includes HLA-B27, sarcoidosis, phacogenic anaphylaxis, endophthalmitis, syphilis, TB, Behçet disease, herpetic, rifabutin, and the pseudohypopyon of lymphoma, leukemia, retinoblastoma, or triamcinolone.

A shifting hypopyon (moves with head position) suggests Behçet disease, lymphoma, or pseudohypopyon from prior triamcinolone injection.

Low intraocular pressure (IOP) (more common, secondary to ciliary body hyposecretion), elevated IOP (e.g., herpetic, lens induced, FHIC, Posner–Schlossman syndrome), fibrin (e.g., HLA-B27, endophthalmitis), iris nodules (e.g., sarcoidosis, syphilis, TB), iris atrophy (e.g., herpetic, fourth-generation fluoroquinolones), iris heterochromia (e.g., FHIC), iris synechiae (especially HLA-B27, sarcoidosis), band keratopathy (especially JIA in younger patients, any chronic uveitis in older patients), uveitis in a “quiet eye” (consider JIA, FHIC, and masquerade syndromes), and CME (see Figure 12.1.1).

Diagnostic Categories

Tight (contact) lens syndrome. See 4.21, Contact Lens-Related Problems.

Neoplasms: Pseudohypopyon of retinoblastoma (in children), leukemia, and lymphoma; recurrent hyphema of juvenile xanthogranuloma (in children), metastatic disease.

Ocular ischemic syndrome (OIS). See 11.11, Ocular Ischemic Syndrome/Carotid Occlusive Disease.

Pigmentary dispersion syndrome. See 9.9, Pigment Dispersion Syndrome/Pigmentary Glaucoma.

Schwartz–Matsuo syndrome–pigmentary cells released from a chronic retinal detachment move into AC and trabecular meshwork causing elevated IOP.