Red eye, pain, foreign body sensation, photophobia, tearing, decreased vision, skin (e.g., eyelid) vesicular rash, history of previous episodes; usually unilateral.

Primary HSV infection is usually not apparent clinically. However, neonatal primary herpes infection is a rare, potentially devastating disease associated with localized skin, eye, or oral infection and severe central nervous system and multiorgan system infection (see 8.9, Ophthalmia Neonatorum [Newborn Conjunctivitis]). Compared to adults, children tend to exhibit more severe disease that may be bilateral, recurrent, and associated with extensive eyelid involvement, multiple corneal/conjunctival dendrites, as well as a greater degree of secondary corneal scarring/astigmatism. Possible triggers for recurrence include ocular surgery, certain topical medications, fever, stress, menstruation, and upper respiratory tract infection. Infection may be characterized by any or all of the following:

Eyelid/Skin Involvement

Clear vesicles on an erythematous base that progress to crusting, heal without scarring, and cross dermatomes, but are typically unilateral (only 10% of primary HSV dermatitis is bilateral).

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctival injection with acute unilateral follicular conjunctivitis, with or without conjunctival dendrites or geographic ulceration.

Epithelial Keratitis

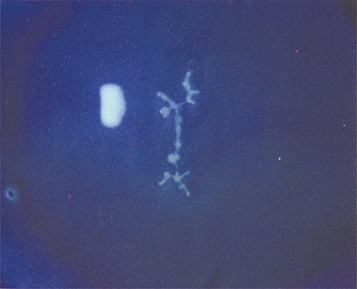

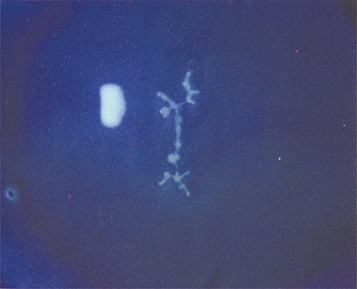

(See Figure 4.16.1.)

Figure 4.16.1: Herpes simplex dendritic keratitis.

May be seen as macropunctate keratitis, dendritic keratitis (a thin, linear, branching epithelial ulceration with club-shaped terminal bulbs at the end of each branch), or a geographic ulcer (a large, amoeba-shaped corneal ulcer with a dendritic edge). The edges of herpetic lesions are heaped up with swollen epithelial cells that stain well with rose bengal or lissamine green; the central ulceration stains well with fluorescein. Corneal sensitivity may be decreased. Subepithelial scars and haze (ghost dendrites) may develop as epithelial dendrites resolve. Epithelial keratitis is considered to be live, replicating viral disease, and treatment is directed accordingly.

Differential Diagnosis of Corneal Dendrites

A “true” dendrite (branching epithelial ulceration with terminal end-bulbs) is pathognomonic for HSV however there are many similar appearing lesions that should be distinguished:

VZV: Pseudodendrites in VZV are slightly elevated and are without central ulceration. They do not have true terminal bulbs and typically stain poorly with fluorescein. See 4.17, Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus/Varicella Zoster Virus.

Recurrent corneal erosion or any recent corneal abrasion: A healing epithelial defect often has a dendritiform appearance. Recurrent erosions in patients with lattice dystrophy can have a geographic shape. See 4.2, Recurrent Corneal Erosion.

Acanthamoeba keratitis pseudodendrites: History of soft contact lens wear, pain often out of proportion to inflammation, chronic course, not responding to antiviral therapy. These are raised epithelial lesions, not epithelial ulcerations. See 4.14, Acanthamoeba Keratitis.

Others: Cornea verticillata from medications or Fabry disease, and rarely tyrosinemia.

Stromal Keratitis

Stromal keratitis without ulceration (alternate terms: non-necrotizing keratitis, immune stromal keratitis, IK): Unifocal or multifocal stromal haze or whitening, often with stromal edema, in the absence of epithelial ulceration. Accompanying stromal vascularization indicates chronicity or prior episodes. The differential of stromal keratitis without ulceration includes any cause of IK (see 12.18, Interstitial Keratitis). HSV stromal keratitis is considered an immune reaction rather than active infectious process and therefore treatment is directed accordingly.

Stromal keratitis with ulceration (necrotizing keratitis): Suppurative stromal inflammation, thinning, with an adjacent or overlying epithelial defect. Appearance may be indistinguishable from infectious keratitis (fungal, bacterial, parasitic), and therefore infection should be ruled out. Stromal keratitis may lead to thinning or scarring and therefore must be treated diligently.

Endothelial Keratitis

Neurotrophic Ulcer

A chronic presentation in a relatively neurotrophic cornea due to fifth cranial nerve sensory damage following prior keratitis. A sterile ulcer with smooth epithelial margins over an area of interpalpebral stromal disease that persists or worsens despite antiviral therapy. May be associated with stromal melting and perforation. In patients without a known history or HSV keratitis, other causes of neurotrophic keratitis should be considered, including: VZV, diabetes, cranial surgery, or radiation.

Uveitis

Retinitis

Rare. See 12.13, Acute Retinal Necrosis.

Blepharoconjunctivitis: Skin/Eyelid/Conjunctivitis

Self-limited, however, treatment may shorten course and reduce corneal exposure to live virus. Systemic (acyclovir 400 mg five times daily or valacyclovir 500 mg twice daily or famciclovir 250 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days) or topical (ganciclovir 0.15% ophthalmic gel five times daily or trifluridine 1% nine times daily for 7 to 10 days) therapy may be helpful.

Epithelial Keratitis

Either systemic or topical antiviral therapy may be used. Many cornea specialists now prefer systemic treatment for greater intraocular concentration, ease of use, and reduction of corneal medication toxicity.

Dendritic: Oral treatment: acyclovir 400 mg five times daily or valacyclovir 500 mg two to three times daily or famciclovir 250 mg two to three times daily for 7 to 10 days. Topical treatment: ganciclovir 0.15% ophthalmic gel or 3% acyclovir ophthalmic ointment five times per day until healed, then three times per day for 7 days or trifluridine 1% drops nine times per day until healed then five times daily for 7 days (but not exceeding 21 days). Topical ganciclovir gel and acyclovir ointment have a much lower incidence of corneal toxicity than trifluridine drops.

Geographic: Oral treatment (acyclovir 400 to 800 mg five times daily or valacyclovir 500 to 1,000 mg two to three times daily or famciclovir 250 to 500 mg two to three times daily) for 14 to 21 days or topical therapy as described above.

Consider cycloplegic drop (e.g., cyclopentolate 1% b.i.d.) if an anterior chamber reaction or photophobia is present.

Topical antibiotic (drop or ointment) may be given at a prophylaxis dose to prevent bacterial superinfection until epithelium is healed.

Patients taking topical steroids should have them tapered rapidly.

Limited debridement of infected epithelium can be used as an adjunct to antiviral agents.

Technique: After topical anesthetic instillation, a sterile, moistened cotton-tipped applicator or semisharp instrument is used carefully to peel off the lesions at the slit lamp. After debridement, antiviral treatment should be instituted or continued as described earlier.

For epithelial defects that do not resolve after 1 to 2 weeks, bacterial coinfection or acanthamoeba keratitis should be suspected. Noncompliance and topical antiviral toxicity should also be considered. At that point, the topical antiviral agent should be discontinued, and a nonpreserved artificial tear ointment or an antibiotic ointment (e.g., erythromycin) should be used four to eight times per day for several days with careful follow-up. Smears for Acanthamoeba should be performed whenever the diagnosis is suspected.

Stromal Keratitis Without Epithelial Ulceration

Therapeutic dose topical steroid: Prednisolone acetate 1% six to eight times daily tapered slowly. Patients may require low-dose/potency maintenance therapy indefinitely.

Prophylactic oral antiviral: Acyclovir 400 mg twice daily or valacyclovir 500 mg once or twice daily or famciclovir 250 mg once or twice daily.

Microbial superinfections must be ruled out and treated.

Stromal Keratitis With Epithelial Ulceration

Limited dose of topical steroid: Prednisolone acetate 1% twice daily.

Therapeutic dose of oral antiviral for 7 to 10 days: Acyclovir 800 mg three to five times daily or valacyclovir 1 g two to three times daily or famciclovir 500 mg two to three times daily. The oral antiviral agent is reduced to prophylactic dose as long as topical steroids are continued.

Tissue adhesive or corneal transplantation may be required if the cornea perforates.

Endothelial Keratitis

Therapeutic dose of topical steroid and therapeutic dose of oral antiviral (see dosing above).

Neurotrophic Ulcer

See 4.6, Neurotrophic Keratopathy.

|

NOTE NOTEChronic use of prophylactic oral antivirals may help prevent subsequent episodes of HSV keratouveitis. |

|

NOTE NOTETopical steroids are contraindicated in those with infectious epithelial disease. Rarely, a systemic steroid (e.g., prednisone 40 to 60 mg p.o. daily tapered rapidly) is given to patients with severe necrotizing stromal disease accompanied by an epithelial defect and hypopyon. Cultures should be done to rule out a superinfection. Valacyclovir has greater bioavailability than acyclovir. Little has been published on famciclovir for HSV, but it may be better tolerated in patients who have side effects to acyclovir such as headache, fatigue, or gastrointestinal upset. Dosing of antivirals discussed above (e.g., acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir) needs to be adjusted in patients with renal insufficiency. Checking BUN and creatinine is recommended in patients at risk for renal disease before starting high doses of these medications. Valacyclovir should be used with caution in patients with human immunodeficiency virus due to reports of thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic uremic syndrome in this population. The persistence of an ulcer with stromal keratitis is commonly due to the underlying inflammation (requiring cautious steroid therapy); however, it may be due to antiviral toxicity, active HSV epithelial infection, or neurotrophic keratopathy. When an ulcer deepens, a new infiltrate develops, or the anterior chamber reaction increases, smears and cultures should be considered for bacteria and fungi. See Appendix 8, Corneal Culture Procedure.

|