Acute unilateral vision loss, redness, blurred vision, floaters, ocular pain, and photophobia. Affected patients are usually immunocompetent.

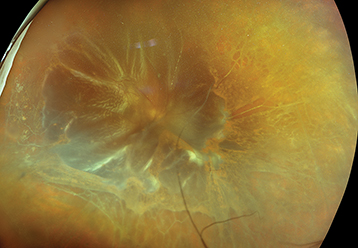

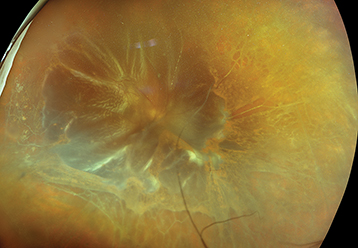

(See Figures 12.13.1 and 12.13.2.)

Figure 12.13.1: The triad of retinitis, vasculitis, and vitritis in a patient with acute retinal necrosis.

Figure 12.13.2: Retinal detachment in a patient with acute retinal necrosis.

Critical

The American Uveitis Society criteria include one or more foci of retinal necrosis with discrete borders in the peripheral retina, rapid progression of disease in the absence of antiviral therapy, circumferential spread, evidence of occlusive vasculopathy with involvement of arterioles, and prominent inflammatory reaction in the AC and/or vitreous. If untreated, the circumferential progression of necrosis may become confluent and spread posteriorly. The macula is typically spared early in the disease course.

Other

AC reaction; KP; conjunctival injection; episcleritis or scleritis; increased IOP; sheathed retinal arterioles and sometimes venules, especially in the periphery; retinal hemorrhages (minor finding); optic disc edema; delayed RRD occurs in approximately 70% of patients secondary to large irregular posterior breaks. Usually begins unilaterally but may involve the second eye in one-third of cases within weeks to months. An optic neuropathy with disc edema or pallor sometimes develops.

See 12.3, Posterior Uveitis.

CMV retinitis: See 12.12, Cytomegalovirus Retinitis.

PORN: Rapidly progressive retinitis characterized by clear vitreous and sheet-like opacification deep to normal-looking retinal vessels, and occasional spontaneous vitreous hemorrhage. PORN is usually found in immunocompromised individuals and frequently leads to rapid bilateral blindness due either to the infection itself or to secondary retinal detachment, making prompt diagnosis and treatment essential. Unlike ARN, pain and vitritis are minimal and macular involvement occurs early.

Syphilis: Pleomorphic uveitis. Can present as a focal necrotizing retinitis. See 12.10, Syphilis.

Toxoplasma retinochoroiditis: Primary toxoplasmosis can appear as a focal or fulminant retinitis (in an immunocompromised patient) without the classic adjacent pigmented chorioretinal scar. See 12.9, Toxoplasmosis.

Behçet disease: Most common posterior manifestation is a vasculitis which may be occlusive and can have an associated focal necrotizing retinitis. See 12.5, Retinal Vasculitis.

Sarcoidosis: Pleomorphic uveitis. Can present as a focal infiltrative retinitis.

Fungal or bacterial endophthalmitis: See 12.17, Endogenous Bacterial Endophthalmitis and 12.18, Endogenous Fungal Endophthalmitis.

Vitreoretinal lymphoma: Consider in patients >50 years of age with refractory unilateral vitritis, yellow-white subretinal infiltrates, absence of pain, or other signs of intraocular inflammation (quiet IVFA).

ARN is a clinical syndrome caused by the herpes virus family: most commonly VZV (older patients), less commonly HSV (younger patients), or rarely, CMV or Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).

See 12.3, Posterior Uveitis, for a nonspecific uveitis workup.

History: Risk factors for AIDS or other immunocompromised states (iatrogenic, autoimmune, malignancy, or genetic)? If yes, the differential diagnosis includes CMV retinitis and PORN. Ask about history of shingles (especially herpes zoster ophthalmicus) or herpes simplex infections. Head trauma (including neurosurgery) and ocular surgery may precipitate ARN. Rarely, ARN can follow localized immunosuppression with periocular or intravitreal corticosteroid injections. Most patients have no identifiable precipitating factors.

Complete ocular examination: Evaluate the AC and vitreous for cells, measure IOP, and perform a dilated fundus examination using indirect ophthalmoscopy; gentle scleral depression as necrotic retina has an increased risk of retinal detachment.

Focused serologic testing based on history and examination:

Treponemal test (syphilis EIA, FTA-ABS, TP-PA), followed by confirmatory nontreponemal test (RPR, VDRL). See 12.10, Syphilis.

Interferon gamma releasing assay (IGRA, QuantiFERON Gold) and/or PPD. Consider chest imaging (CXR or CT chest) to assess for signs of active or prior pulmonary disease.

In those at risk for TB (e.g., immigrants from high-risk areas such as India, HIV-positive patients), homeless patients, or prisoners.

If considering immunosuppressive therapy (especially biologics).

Serologic testing for antibodies against HSV, VZV, CMV, and toxoplasmosis can be useful in ruling out a disease as the causative etiology (IgG and/or IgM negative). The presence of positive IgG titer is not necessarily indicative of active disease, but rather prior exposure. Very elevated IgG titers may make you more suspicious for active disease, and a positive IgM indicates recent infection, but again are not fully diagnostic. Negative testing helps to rule out the disease.

ACE, lysozyme, and chest imaging (CXR or CT chest).

Consider HIV testing.

Consider an AC paracentesis to detect DNA for HSV, VZV, CMV, and toxoplasmosis-associated disease. See Appendix 13, Anterior Chamber Paracentesis.

Consider IVFA to identify retinal vasculitis and areas of ischemia.

Ultrawide field imaging may be useful in documenting and following up peripheral lesions.

Consider MRI of the brain and orbits with and without contrast and lumbar puncture if large cell lymphoma, tertiary syphilis, encephalitis, or optic nerve dysfunction is suspected.