HSV/VZV: Associated retinal vasculitis is most commonly seen in association with ARN syndrome (retinitis, vasculitis, and vitritis), but can occur in isolation. Most frequently is an occlusive vasculitis. See 12.13, Acute Retinal Necrosis.

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated:

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly Churg–Strauss disease): ANCA-associated vasculitis featuring obstructive airway disease (asthma), nasal polyps, elevated eosinophils, and mononeuritis multiplex (e.g., foot or wrist drops).

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly Wegener granulomatosis): ANCA-associated vasculitis featuring nephritis, orbital inflammation, sinusitis, and pulmonary inflammation.

Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN): Three major criteria (retinal vasculitis, aneurysmal dilations at arterial bifurcations, and neuroretinitis) and three minor criteria (peripheral capillary nonperfusion, retinal neovascularization, and macular exudation). The etiology is unknown. Typically seen in young or middle-aged patients.

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN): Multisystem medium vessel vasculitis that often presents with hypertension, renal failure, neuropathy, and rash. More common in males ages 40 to 60 years. Can be associated with hepatitis B.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): Typically presents with cotton-wools spots, retinal hemorrhage, and vascular occlusions. May be caused by either immune complex deposition in retinal vessels or by antiphospholipid syndrome. Multisystem disease with the most frequent manifestations including arthritis, myalgia, butterfly rash, and renal dysfunction.

CMV: Associated retinal vasculitis is most commonly seen in the setting of severe immunosuppression and CMV retinitis. See 12.12, Cytomegalovirus Retinitis.

HIV retinopathy: Presents with cotton-wool spots, retinal hemorrhages, and microaneurysms. See 12.11, HIV Retinopathy.

MS: Most commonly presents as intermediate uveitis, but can also have a segmental phlebitis.

Sarcoidosis: Pleomorphic uveitis. When affecting the retinal vessels it is classically a phlebitis with yellow exudates or “candlewax drippings.” Can be occlusive.

TB: Pleomorphic uveitis. When causing a retinal vasculitis it preferentially affects the venules. Can be occlusive.

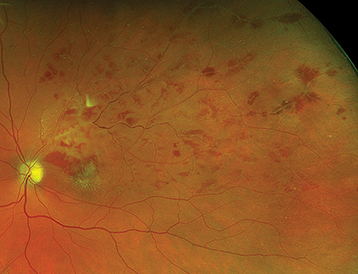

Behçet disease: Typical demographic is aged 20 to 40 years, especially in patients of Japanese, Turkish, or Middle Eastern descent. Other than vasculitis, ocular manifestations include bilateral “shifting” hypopyon (due to lack of fibrin in the AC reaction), vitritis, waxy optic nerve pallor, focal necrotizing retinitis, and scleritis. Systemic features necessary for diagnosis include painful oral aphthous ulcers (well-defined borders with a white-yellow necrotic center, often with surrounding erythema, found in 98% to 100% of patients) at least three times per year and two of the following: genital ulcers, skin lesions, positive Behçetine (pathergy) test (formation of a local pustule that appears 48 hours after skin puncture with a needle), and eye lesions. Other systemic features include arthritis, hemoptysis from pulmonary artery involvement, renal involvement, gastrointestinal disease with bowel ulceration, epididymitis, neuro-Behçet (e.g., vasculitis, encephalitis, cerebral venous thrombosis, neuropsychiatric symptoms), and skin findings (erythema nodosum, pseudofolliculitis, palpable purpura, superficial thrombophlebitis, or dermographism) (see Figure 12.5.1).

IBD-associated: More commonly associated with Crohn disease. Causes a mild–moderate intermediate uveitis with peripheral vasculitis.

Syphilis: Pleomorphic uveitis which can affect retinal arterioles and venules. See 12.10, Syphilis.

Giant cell arteritis (GCA): Occlusive vasculitis of medium and large blood vessels that can rapidly result in severe ischemic vision loss in both eyes. See 10.17, Arteritic Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (Giant Cell Arteritis).

Susac syndrome: Triad of retinal arteriolar occlusions (not at branch points), encephalopathy (lesions are classically located in the corpus callosum), and sensorineural hearing loss.