Pain, blurred vision, colored halos around lights, frontal headache, nausea, and vomiting.

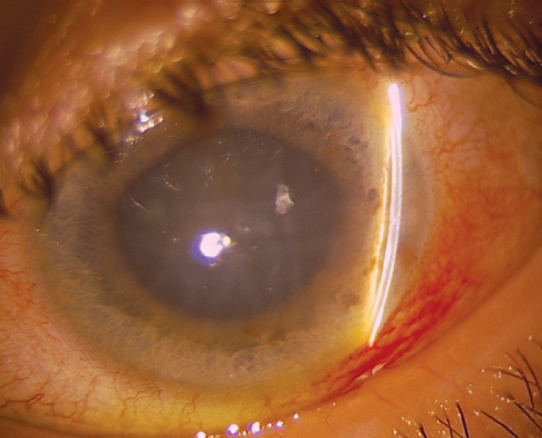

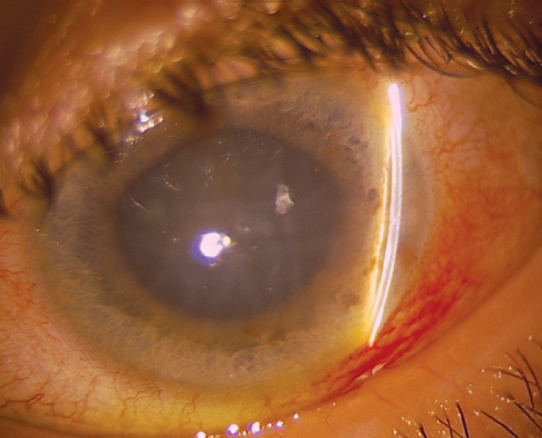

(See Figure 9.4.1.)

Figure 9.4.1: Acute angle closure glaucoma with mid-dilated pupil, shallow anterior chamber, and corneal edema.

Critical

Closed angle in the involved eye, acutely increased IOP, and microcystic corneal edema. Narrow or occludable angle in the fellow eye in cases of primary angle closure.

Other

Conjunctival injection; fixed, mid-dilated pupil.

Differential Diagnosis of Acute IOP Increase With an Open Angle

Inflammatory open-angle glaucoma: See 9.7, Uveitic Glaucoma.

Traumatic (hemolytic) glaucoma: Red blood cells in the anterior chamber. See 3.7, Hyphema and Microhyphema.

Pigmentary glaucoma: Characteristic angle changes (e.g., heavily pigmented TM, Sampaolesi line); vertical pigment deposition on endothelium (Krukenberg spindle); pigment cells floating in the anterior chamber; radial iris transillumination defects (TIDs); pigment line on the posterior lens capsule alongside posterior zonule attachment line (Zentmayer or Scheie line). See 9.9, Pigment Dispersion Syndrome/Pigmentary Glaucoma.

Pseudoexfoliation glaucoma: Grayish-white flaky proteinaceous material deposited throughout anterior segment structures and TM (usually irregular pigment most prominent inferiorly). Classically occurs in patients of European descent. Iris TIDs along pupillary margin often present. See 9.10, Pseudoexfoliation Syndrome/Exfoliative Glaucoma.

Lens-related glaucoma: Leakage of lens material through an intact capsule, usually in the setting of a mature cataract (phacolytic); lens material in the anterior chamber through a violation of the anterior lens capsule after trauma or retained following intraocular surgery (lens particle); or a chronic granulomatous uveitis in response to leaked lens material (phacoantigenic, formerly phacoanaphylaxis). See 9.11, Lens-Related Glaucoma.

Glaucomatocyclitic crisis (Posner–Schlossman syndrome): Recurrent IOP spikes in one eye, mild cell, and flare with or without fine keratic precipitates (KP). See 9.7, Uveitic Glaucoma.

Retrobulbar hemorrhage or inflammation. See 3.20, Traumatic Retrobulbar Hemorrhage (Orbital Hemorrhage).

Carotid–cavernous fistula: See 7.7, Miscellaneous Orbital Diseases.

Etiology of Primary Angle Closure

Pupillary block: Apposition of the lens and the posterior iris at the pupil leads to blockage of aqueous humor flow from the posterior chamber to the anterior chamber. This mechanism leads to increased posterior chamber pressure, forward movement of the peripheral iris, and subsequent obstruction of the TM. Predisposed eyes have a narrow anterior chamber angle recess, a short axial length, and thick lens. Risk factors include increased age, East Asian descent, female sex, hyperopia, and family history. May be precipitated by topical mydriatics or, rarely, miotics; systemic anticholinergics (e.g., antihistamines and antidepressants); accommodation (e.g., reading); or dim illumination. Fellow eye has similar anatomy.

Angle crowding as a result of an abnormal iris configuration including high peripheral iris roll or plateau iris syndrome angle closure. See 9.12, Plateau Iris.

Etiology of Secondary Angle Closure

PAS pulling the angle closed: Causes include uveitis, inflammation, and LT. See 9.5, Chronic Angle Closure Glaucoma.

Neovascular or fibrovascular membrane pulling the angle closed: See 9.13, Neovascular Glaucoma.

Membrane obstructing the angle: Causes include endothelial membrane in iridocorneal endothelial syndrome (ICE) and posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD), epithelial membrane in epithelial downgrowth, and fibrous ingrowth (may follow penetrating trauma). See 9.14, Iridocorneal Endothelial Syndrome.

Lens-induced narrow angles: Iris–TM contact as a result of a large lens (phacomorphic), small lens with anterior prolapse (e.g., microspherophakia), small eye (nanophthalmos), or zonular loss/weakness (e.g., trauma, advanced pseudoexfoliation, Marfan syndrome).

Aphakic or pseudophakic pupillary block: Iris bombé configuration secondary to occlusion of the pupil by the anterior vitreous or fibrous adhesions. May also occur with anterior chamber intraocular lenses.

Topiramate- and sulfonamide-induced angle closure: Usually after increase in dose or within first 2 weeks of starting medication. Usually bilateral angle closure due to supraciliary effusion and ciliary body swelling with subsequent anterior rotation of the lens–iris diaphragm. Myopia is induced secondary to anterior displacement of ciliary body and lens along with lenticular swelling.

Choroidal swelling: Following extensive retinal laser surgery, placement of a tight encircling scleral buckle, retinal vein occlusion, and others.

Posterior segment tumor: Malignant melanoma, retinoblastoma, ciliary body tumors, and others. See 11.36, Choroidal Nevus and Malignant Melanoma of the Choroid.

Hemorrhagic choroidal detachment: See 11.27, Choroidal Effusion/Detachment.

Aqueous misdirection syndrome. See 9.16, Aqueous Misdirection Syndrome/Malignant Glaucoma.

Developmental abnormalities: Axenfeld–Rieger spectrum, Peters anomaly, persistent fetal vasculature, and others. See 8.14, Developmental Anterior Segment and Lens Anomalies/Dysgenesis.

Depends on etiology of angle closure, severity, and duration of attack. Severe, permanent damage may occur within several hours. If visual acuity is hand motion or better, IOP reduction is usually urgent; therapeutic intervention should include all topical glaucoma medications, systemic (preferably intravenous) CAI, and in some cases intravenous osmotic agent (e.g., mannitol) as long as not contraindicated. Paracentesis with a 30-gauge needle on an open tuberculin syringe directed toward the 6 o’clock position will bring down the pressure immediately. See 9.13, Neovascular Glaucoma, 9.15, Postoperative Glaucoma, and 9.16, Aqueous Misdirection Syndrome/Malignant Glaucoma.

Compression gonioscopy is essential to determine whether the trabecular blockage is reversible and may break an acute attack.

Topical therapy with β-blocker ([e.g., timolol 0.5%] caution with asthma, COPD, and bradycardia), α2 agonist (e.g., brimonidine 0.1%), prostaglandin analog (e.g., latanoprost 0.005%), rho kinase inhibitor (e.g., netarsudil 0.02% q.d.), and CAI (e.g., dorzolamide 2%) should be initiated immediately. In urgent cases, three rounds of these medications may be given, with each round being separated by 15 minutes.

Topical steroid (e.g., prednisolone acetate 1%) may be useful in reducing corneal edema.

Systemic CAI (e.g., acetazolamide 250 to 500 mg i.v. or two 250-mg tablets p.o. in one dose if unable to give i.v.) if reduction in IOP is urgent or if IOP is refractory to topical therapy. Do not use in sulfonamide-induced angle closure or sickle cell disease.

Recheck the IOP in 1 hour. If IOP reduction is urgent or refractory to therapies listed above, repeat topical medications and give osmotic agent (e.g., mannitol 1 to 2 g/kg i.v. over 45 minutes [note: a 500-mL bag of mannitol 20% contains 100 g of mannitol]). Contraindicated in congestive heart failure, renal disease, and intracranial bleeding.

|

NOTE NOTEPrior to initiation of systemic CAIs or osmotic agents, consider testing renal function. |

When acute angle closure attack is the result of:

Phakic pupillary block or angle crowding: Historically, pilocarpine, 1% to 2%, every 15 minutes for two doses was recommended but has fallen out of favor by some physicians due to adverse effects such as headache, accommodative spasm, associated increased risk for uveitis and retinal detachment, and potential for miosis-induced angle closure.

Aphakic or pseudophakic pupillary block or secondary closure of the angle: Do not use pilocarpine. Consider a mydriatic and a cycloplegic agent (e.g., cyclopentolate 1% to 2%, and phenylephrine 2.5% every 15 minutes for four doses) when laser or surgery cannot be performed because of corneal edema, inflammation, or both.

Topiramate- or sulfonamide-induced secondary angle closure: Do not use CAIs in sulfonamide-induced angle closure. Immediately discontinue the inciting medication. Treat with cycloplegia to induce posterior rotation of the ciliary body (e.g., atropine 1% b.i.d. or t.i.d.) and topical steroids (e.g., prednisolone 1% q.i.d.). Consider hospitalization and treatment with intravenous hyperosmotic agents and intravenous steroids (e.g., methylprednisolone 250 mg i.v. every 6 hours) for cases of markedly elevated IOP unresponsive to other treatments. Cases involving large ciliochoroidal or choroidal effusions may benefit from intravenous corticosteroids, as inflammation may play a role in their formation. If unresponsive, drainage of the effusion may be required. Peripheral iridotomy (PI) or iridectomy and miotics are not indicated.

In phacomorphic glaucoma, the lens should be removed as soon as the eye is quiet and the IOP controlled, if possible. See 9.11.4, Phacomorphic Glaucoma.

Address systemic problems such as pain and vomiting.

For pupillary block (all forms) or primary angle crowding: If the IOP decreases significantly, definitive treatment with yttrium–aluminum–garnet (YAG) laser PI or surgical iridectomy is performed once the cornea is clear and the anterior chamber is quiet, typically 1 to 5 days after attack.

|

NOTE NOTEIf the affected eye is too inflamed initially for laser PI, perform laser PI of the fellow eye first. An untreated fellow eye has a 40% to 80% chance of acute angle closure in 5 to 10 years. Repeated angle closure attacks with a patent PI may indicate plateau iris syndrome. See 9.12, Plateau Iris. |

Patients are discharged on a regimen of maintenance dose IOP-lowering drops and oral medications (described above), as well as topical steroids if inflamed. Close monitoring with IOP measurement each day is necessary immediately after an angle closure attack. Once the IOP has been reasonably reduced, follow-up frequency is guided by overall clinical response and stability. On occasion, topical steroids in addition to IOP-lowering medications are necessary for 4 to 7 days to increase the chance of successful iridotomy.

|

NOTE NOTEIf IOP does not decrease after two courses of maximal medical therapy, a laser (YAG) PI should be considered if there is an adequate view of the iris. If IOP still does not decrease after more than one attempt at laser PI, then a laser iridoplasty, surgical PI, or cataract surgery is needed, depending on the etiology. A guarded filtration procedure should also be considered based on the severity of glaucoma and anticipated IOP control after definitive treatment. If IOP remains elevated and the angle remains closed despite a patent iridectomy, surgical treatment of chronic angle closure is indicated. |

For secondary angle closure: Treat the underlying problem. Consider argon laser iridoplasty to open the angle, particularly in plateau iris syndrome or nanophthalmos. Goniosynechiolysis combined with cataract surgery can be performed for chronic angle closure of <6 months’ duration. Systemic steroids may be required to treat serous choroidal detachments secondary to inflammation.

After definitive treatment, patients are reevaluated in weeks to months initially and then less frequently. Visual fields and disc imaging are obtained for baseline purposes.

|

NOTE NOTECardiovascular status and electrolyte balance must be considered when contemplating osmotic agents, CAIs, and β-blockers. The corneal appearance may worsen when the IOP decreases. Worsening vision or spontaneous arterial pulsations are signs of increasing urgency for pressure reduction. Since one-third to one-half of first-degree relatives may have occludable angles, patients should be counseled to alert relatives to the importance of screening. Angle-closure glaucoma may be seen without an increased IOP. The diagnosis should be suspected in a patient who had episodes of pain and reduced acuity and is noted to have: An edematous, thickened cornea. Normal or markedly asymmetric pressure in both eyes. Shallow anterior chambers in both eyes. Occludable anterior chamber angle in the fellow eye.

|