Definition

Glaucoma caused by a fibrovascular membrane overgrowing the anterior chamber angle structures. Initially, despite an open appearance on gonioscopy, the angle may be blocked by the membrane. The fibrovascular membrane eventually contracts, causing PAS formation and secondary angle-closure glaucoma. Rarely, it may have NV of the angle without NV of the iris (NVI) at the pupillary margin. Ischemia-driven vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) released from a variety of causes results in the formation of the fibrovascular membrane.

May be asymptomatic or include pain, redness, photophobia, and decreased vision.

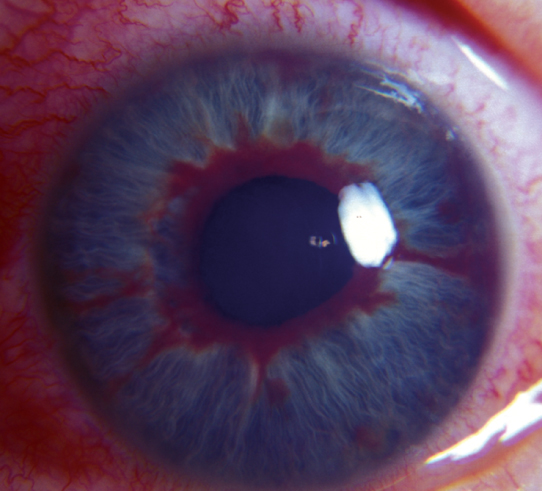

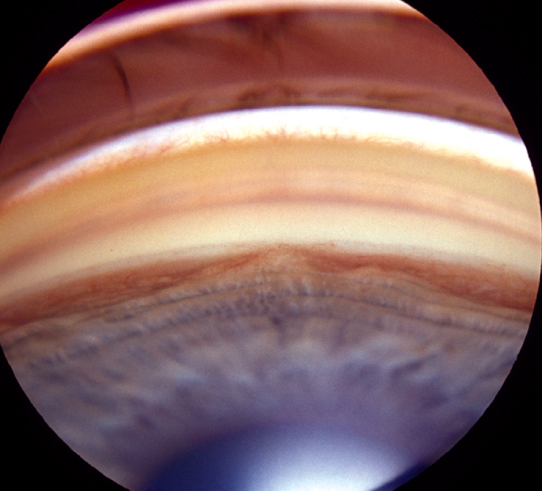

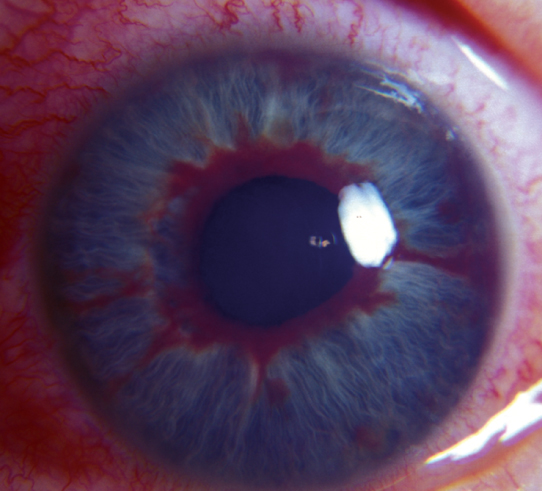

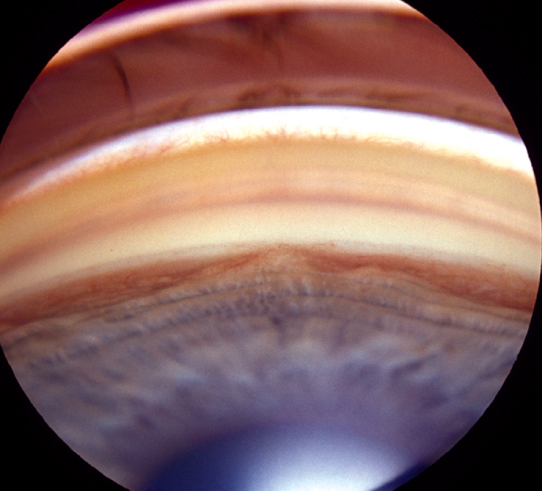

(See Figures 9.13.1 and 9.13.2.)

Figure 9.13.1: Iris neovascularization.

Figure 9.13.2: Neovascularization of the angle.

Critical

Stage 1: Nonradial, misdirected blood vessels along the pupillary margin, the TM, or both. No signs of glaucoma. Normal iris blood vessels run radially and are typically symmetric.

Stage 2: Stage 1 plus increased IOP (open-angle neovascular glaucoma).

Stage 3: Partial or complete angle-closure glaucoma caused by a fibrovascular membrane pulling the iris well anterior to the TM (usually at the level of Schwalbe line). NVI is common.

Other

Mild anterior chamber cell and flare, conjunctival injection, corneal edema with acute IOP increase, hyphema, eversion of pupillary margin allowing visualization of iris pigment epithelium (ectropion uveae), optic nerve cupping, and visual field loss.

The presence of NVI, especially with high IOP, requires urgent therapeutic intervention, usually within 1 to 2 days. Angle closure can proceed rapidly (days to weeks).

|

NOTE NOTENVI without glaucoma is managed similarly, but there is no need for pressure-reducing agents unless IOP increases. |