A. Systemic Complaints

Fever, night sweats, and weight loss are common symptoms in people with HIV and may occur without a complicating opportunistic infection. Patients with persistent fever and no localizing symptoms should nonetheless be carefully examined and evaluated with a CXR (Pneumocystis pneumonia can present with subtle respiratory symptoms), bacterial blood cultures if the fever is greater than 38.0°C, as well as serum cryptococcal antigen and mycobacterial cultures of the blood in those with low CD4 cell counts. Abdominal CT scans can be considered to evaluate occult intrabdominal infections or cancers. If these studies return unremarkable results, patients should be observed closely. Antipyretics are useful to prevent dehydration.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2018 quick reference guide: recommended laboratory HIV testing algorithm for serum or plasma specimens. http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/50872 ErlandsonKMet al. HIV and aging: reconsidering the approach to management of comorbidities. Infect Dis Clin North Am.2019;33:769. [PMID: 31395144] PahwaSet al. NIH Workshop on HIV-associated comorbidities, coinfections, and complications: summary and recommendation for future research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86:11. [PMID: 33306561] |

1. Weight Changes

Weight loss is a particularly distressing complication of long-standing HIV infection. Patients typically have disproportionate loss of muscle mass, with maintenance or less substantial loss of fat stores. The mechanism of HIV-related weight loss is not completely understood but appears to be multifactorial, with some of the older thymidine analog medications implicated. In the setting of the newer medications, weight gain has been seen with some ART regimens, with integrase strand transfer inhibitors associated with greater weight gain than protease inhibitors or nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Among nucleoside/tide reverse transcriptase inhibitors, tenofovir alafenamide is associated with greater weight gain than tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or abacavir.

Exacerbating the decrease in caloric intake, many patients with uncontrolled HIV have an increased metabolic rate. This increased rate has been shown to exist even among asymptomatic people with HIV, but it accelerates with disease progression and secondary infection. People with HIV with secondary infections also have decreased protein synthesis, which makes maintaining muscle mass difficult.

Two pharmacologic approaches for increasing appetite and weight gain are the progestational agent megestrol acetate liquid suspension (400-800 mg orally daily in divided doses) and the antiemetic agent dronabinol (2.5-5 mg orally three times a day), but neither of these agents increases lean body mass. Side effects from megestrol acetate are rare, but thromboembolic phenomena, edema, nausea, vomiting, and rash have been reported. In 3-10% of patients using dronabinol, euphoria, dizziness, paranoia, and somnolence and even nausea and vomiting have been reported. Dronabinol contains only one of the active ingredients in marijuana, and some patients experience better relief of nausea and improvement of appetite with medical cannabis (THC is thought to be more effective than CBD; administered via smoking, vaporization, essential oils, or cooked in food). In the United States, 38 states and the District of Columbia have legalized medical marijuana, and 23 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational (nonmedical) use. However, the use and sale of marijuana are still illegal under federal law.

BadowskiMEet al. Dronabinol oral solution in the management of anorexia and weight loss in AIDS and cancer. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:643. [PMID: 29670357] SaeteawMet al. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological cachexia interventions: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021;11:75. [PMID: 33246937] |

2. Nausea

Nausea leading to weight loss is sometimes due to esophageal candidiasis. Patients with oral candidiasis and nausea should be empirically treated with an oral antifungal agent. Patients with weight loss due to nausea of unclear origin may benefit from use of antiemetics or promotility agents prior to meals (ondansetron, 8 mg three times daily; prochlorperazine, 10 mg three times daily; or metoclopramide, 10 mg three times daily). Dronabinol (5 mg three times daily) or medical cannabis can also be used to treat nausea, although in some individuals it can worsen nausea and vomiting. Depression and adrenal insufficiency are two potentially treatable causes of weight loss.

HallVP.Common gastrointestinal complications associated with human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS: an overview. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am.2018;30:101. [PMID: 29413205] UnalEet al. Cannabinoids: a guide for use in the world of gastrointestinal disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54:769. [PMID: 31789770] |

B. Pulmonary Disease

1. Pneumocystis Pneumonia

(See also Part 38.) P jirovecii pneumonia is the most common opportunistic infection associated with AIDS. Pneumocystis pneumonia may be difficult to diagnose because the symptoms-fever, cough, and shortness of breath-are nonspecific and typically subacute. Furthermore, the severity of symptoms ranges from fever and no respiratory symptoms through mild cough or dyspnea to frank respiratory distress.

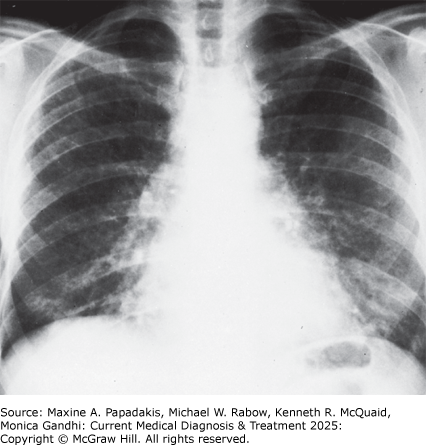

Hypoxemia may be severe, with a PO2 less than 60 mm Hg. The cornerstone of diagnosis is the CXR or CT scan (Figure 33-2). Diffuse or perihilar infiltrates are most characteristic, but only two-thirds of patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia have this finding. Normal CXRs are seen in 5-10% of patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia, although sensitivity is increased with CT scanning, while the remainder have diffuse ground glass opacities. Severe cases can lead to pneumothoraces. Large pleural effusions are uncommon with Pneumocystis pneumonia; their presence suggests bacterial pneumonia, other infections such as tuberculosis, or pleural Kaposi sarcoma.

Figure 33-2. Pneumocystis Pneumonia in a Haitian Woman (She/Her) in Whom Underlying HIV/AIDS is Suspected

Pneumocystis pneumonia in a Haitian woman (she/her) in whom underlying HIV/AIDS is suspected. Typical CXR showing bilateral diffuse interstitial infiltrates extending out from the hilar areas. (Reproduced, with permission, from Grippi MA, Elias JA, Fishman JA et al (editors). Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders, 5th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2015.)

Definitive diagnosis can be obtained in 70-90% of cases by Wright-Giemsa stain or direct fluorescence antibody (DFA) test of induced sputum. Increasingly, PCR testing is available and has high sensitivity and specificity. Sputum induction is performed by having patients inhale an aerosolized solution of 3% saline produced by an ultrasonic nebulizer. Patients should not eat for at least 8 hours and should not use toothpaste or mouthwash prior to the procedure since they can interfere with test interpretation. The next step for patients with negative sputum examinations in whom Pneumocystis pneumonia is still suspected should be bronchoalveolar lavage. This technique establishes the diagnosis in over 95% of cases.

In patients with symptoms suggestive of Pneumocystis pneumonia but with negative or atypical CXRs and negative sputum examinations, other diagnostic tests may provide additional information in deciding whether to proceed to bronchoalveolar lavage. Elevation of serum LD occurs in 95% of cases of Pneumocystis pneumonia, but the specificity of this finding is at best 75%. A normal serum beta-glucan test makes Pneumocystis pneumonia unlikely, although a variety of factors can cause a false-positive serum beta-glucan test. Either a normal diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO) or a high-resolution CT scan of the chest that demonstrates no interstitial lung disease makes the diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia very unlikely. In addition, a CD4 count greater than 250 cells/mcL within 2 months prior to evaluation of respiratory symptoms makes a diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia unlikely; only 1-5% of cases occur above this CD4 count level (see Figure 33-1). This is true even if the patient previously had a CD4 count lower than 200 cells/mcL but has had an increase with ART. Pneumothoraces can be seen in people with HIV with a history of Pneumocystis pneumonia.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is the preferred treatment of Pneumocystis pneumonia (Table 33-3. Treatment of AIDS-Related Opportunistic Infections and Malignancies (Listed in Alphabetical Order)). In addition to specific anti-Pneumocystis treatment, corticosteroid therapy has been shown to improve the course of patients with moderate to severe P jirovecii pneumonia (PaO2 less than 70 mm Hg on room air or alveolar-arterial O2 gradient greater or equal to 35 mm Hg) when administered within 72 hours of the start of anti-Pneumocystis treatment. Steroids should be started as early as possible after initiation of treatment, using prednisone 40 mg orally twice daily for days 1-5, 40 mg daily for days 6-10, and 20 mg daily for days 11-21 (for patients who cannot take oral medication, intravenous methylprednisolone can be substituted at 75% of the oral dose). The mechanism of action for the steroids to improve outcomes is presumed to be a decrease in alveolar inflammation.

Table 33-3. Treatment of AIDS-related opportunistic infections and malignancies1 (listed in alphabetical order).| Infection or Malignancy | Treatment | Complications2 |

|---|---|---|

| Cryptococcal meningitis | Preferred regimen: Induction: Liposomal amphotericin B, 3-4 mg/kg/day intravenously, with flucytosine, 25 mg/kg/dose orally four times daily for minimum of 2 weeks (adjust flucytosine dose for kidney function), then fluconazole, 400 mg orally daily for a minimum of 8 weeks (consolidation), then 200 mg orally daily to complete a minimum of 1 year of therapy (maintenance) | Liposomal amphotericin: fever, chills, hypokalemia, kidney disease Flucytosine: bone marrow suppression, kidney disease, hepatitis Fluconazole: hepatitis |

| Induction: Amphotericin B, 0.7-1.0 mg/kg/day intravenously, with flucytosine, 25 mg/kg/dose orally four times daily for a minimum of 2 weeks (adjust flucytosine dose for kidney function), then fluconazole, 400 mg orally daily for a minimum of 8 weeks (consolidation), then 200 mg orally daily to complete a minimum of 1 year of therapy (maintenance) | Amphotericin: fever, chills, hypokalemia, kidney disease Flucytosine: bone marrow suppression, kidney disease, hepatitis Fluconazole: hepatitis | |

| Fluconazole, used alone, is inferior to amphotericin B as induction therapy; it is recommended only for patients who cannot tolerate or do not respond to the preferred regimen above. If used for primary induction therapy, give fluconazole, 1200 mg orally daily, with flucytosine, 25 mg/kg/dose orally four times daily for a minimum of 2 weeks (adjust flucytosine dose for kidney function), then 400 mg orally daily for a minimum of 8 weeks (consolidation), then 200 mg orally daily to complete a minimum of 1 year of therapy. | Hepatitis | |

| Cytomegalovirus retinitis (immediate sight-threatening) | Preferred regimen: First-line therapy is oral valganciclovir, 900 mg orally twice a day with food for 21 days followed by 900 mg daily (maintenance). For sight-threatening infections involving the macula or optic nerve, add intravitreal ganciclovir (2 mg/injection) or foscarnet (2.4 mg/injection) for 1-4 doses/day for 7-10 days | For valganciclovir: neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia (avoid in patients with hemoglobin < 8 g/dL, neutrophil count below 500 cells/mcL [0.5 × 109 /L] or platelet count below 25,000/mcL [25 × 109 /L]). Potentially embryotoxic. |

| Ganciclovir, 10 mg/kg/day intravenously in two divided doses for 14-21 days, followed by 5 mg/kg daily (maintenance) | Neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia Adjust ganciclovir dose for kidney function. Potentially embryotoxic. | |

| Foscarnet, 90 mg/kg intravenously every 12 hours for 14 days, followed by 90-120 mg/kg once daily | Nausea, hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, azotemia Adjust foscarnet dose for kidney function. | |

| Cidofovir, 5 mg/kg/week intravenously for 2 weeks, then 5 mg/kg every other week with probenecid, 2 g orally 3 hours before dose, 1 g orally 2 hours after dose, and 1 g orally 8 hours after dose | Nephrotoxicity (to reduce likelihood, pre- and post-saline hydration, along with probenecid), ocular hypotony, anterior uveitis, neutropenia Avoid in patients with sulfa allergy because of cross hypersensitivity with probenecid. | |

| Esophageal candidiasis or recurrent vaginal candidiasis | Fluconazole, 100-200 mg orally daily for 14-21 days for esophageal disease and >7 days for recurrent vaginal disease | Hepatitis, development of azole resistance. Fluconazole should not be given to women who are or may be pregnant because of risk of spontaneous abortion. |

| Herpes simplex infection | Acyclovir, 400 mg orally three times daily for 5-10 days; or acyclovir, 5 mg/kg intravenously every 8 hours for severe cases | Resistant herpes simplex with long-term therapy |

| Valacyclovir, 1 g orally twice daily for 5-10 days | Nausea | |

| Famciclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily for 5-10 days | Nausea | |

| Foscarnet, 40 mg/kg intravenously every 8 hours, for acyclovir-resistant cases | Nausea, hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, azotemia Adjust foscarnet dose for kidney function. | |

| Herpes zoster | Preferred regimen: Valacyclovir, 1000 mg orally three times daily for 7-10 days | Nausea |

| Preferred regimen: Famciclovir, 500 mg orally three times daily for 7-10 days | Nausea | |

| Acyclovir, 800 mg orally five times daily for 7-10 days. Intravenous therapy at 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for extensive cutaneous or visceral disease until clinical improvement, then switch to oral therapy to complete a 10- to 14-day course. For ocular involvement, consult an ophthalmologist immediately. | Nausea | |

| Kaposi sarcoma | ||

| Mild to moderate | Initiation or optimization of antiretroviral treatment | Side effects of antiretroviral treatment |

| Advanced disease | Chemotherapy (eg, liposomal doxorubicin or daunorubicin) | Bone marrow suppression, cardiac toxicity |

| Pomalidomide, 5 mg/day orally on days 1-21 of every 28-day cycle; alternative to chemotherapy | Fatigue, asthenia, dyspnea, anemia, neutropenia; contraindicated in pregnancy | |

| Mycobacterium avium complex infection | Clarithromycin, 500 mg orally twice daily, or azithromycin, 600 mg once daily with ethambutol, 15 mg/kg/day orally (maximum, 1 g). May also add: | Clarithromycin: hepatitis, nausea, diarrhea Ethambutol: hepatitis, optic neuritis |

| Rifabutin, 300 mg orally daily | Rash, hepatitis, uveitis | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Combination chemotherapy (eg, R-CHOP and G-CSF). CNS disease: Radiation treatment with dexamethasone for edema | Nausea, vomiting, anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, cardiac toxicity (with doxorubicin) |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii infection3 | Preferred regimen: Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 15 mg/kg/day (based on trimethoprim component) intravenously or one double-strength tablet orally three times a day for 21 days. Add prednisone when PaO2< 70 mm Hg on room air or alveolar-arterial O2 gradient >35 mm Hg: 40 mg orally twice a day on days 1-5, 40 mg orally daily on days 6-10, 20 mg orally daily on days 11-21 | Nausea, neutropenia, anemia, hepatitis, rash, Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| Pentamidine, 3-4 mg/kg/day intravenously for 21 days plus prednisone when indicated as above | Hypotension, hypoglycemia, anemia, neutropenia, pancreatitis, hepatitis | |

| Primaquine, 30 mg/day orally, and clindamycin, 600 mg every 8 hours orally, for 21 days plus prednisone when indicated as above | Primaquine: hemolytic anemia in patients with G6PD deficiency,3 methemoglobinemia, neutropenia, colitis Clindamycin: rash, nausea, abdominal pain, colitis | |

| Not recommended for severe disease: Trimethoprim, 15 mg/kg/day orally in three divided doses, with dapsone, 100 mg/day orally, for 21 days,3 plus prednisone when indicated as above | Nausea, rash, hemolytic anemia in patients with G6PD deficiency3 ; methemoglobinemia (weekly levels should be < 10% of total hemoglobin) | |

| Not recommended for severe disease: Atovaquone, 750 mg orally twice daily with food for 21 days, plus prednisone when indicated as above | Rash, elevated aminotransferases, anemia, neutropenia | |

| Toxoplasmosis | Preferred regimen: Pyrimethamine, 200 mg orally as loading dose, followed by 50 mg daily (weight ≤ 60 kg) or 75 mg daily (weight >60 kg), combined with sulfadiazine, 1000 mg orally four times daily (weight ≤ 60 kg) or 1500 mg orally four times daily (weight >60 kg), and leucovorin, 10-25 mg orally daily, for at least 6 weeks. Longer courses are necessary for extensive disease or incomplete clinical or radiographic resolution. Maintenance therapy with pyrimethamine, 25-50 mg orally, plus sulfadiazine, 2000-4000 mg in two to four divided doses, plus leucovorin, 10-25 mg orally daily. Long-term treatment should be maintained until immune reconstitution with antiretroviral treatment occurs. | Pyrimethamine: leukopenia, anorexia, vomiting Sulfadiazine: nausea, vomiting, Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| For patients who are intolerant of sulfa who cannot be desensitized: Substitute clindamycin, 600 mg intravenously or orally every 6 hours, for the sulfadiazine in the above regimen | Clindamycin: rash, nausea, abdominal pain, colitis | |

| If pyrimethamine not available: Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 10 mg/kg/day (based on trimethoprim component) | Nausea, neutropenia, anemia, hepatitis, rash, Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

1 Recommendations drawn from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. February 11, 2020. Downloaded from http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines on February 14, 2020.

2 List of complications is not exhaustive.

3 Prior to use of primaquine or dapsone, check glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) level in Black patients and those of Mediterranean origin.

G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim); R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone.

FishmanJA.Pneumocystis jirovecii. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:141. [PMID: 32000290] ShibataSet al. Pneumocystis pneumonia in HIV-1-infected patients. Respir Investig.2019;57:213. [PMID: 30824356] TasakaS.Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2020;83:132. [PMID: 32185915] US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV. 2020. http://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infection/whats-new-guidelines |

2. Other Infectious Pulmonary Diseases

Other infectious causes of pulmonary disease in patients with AIDS include bacterial, mycobacterial, and viral etiologies.

Figure 33-3. A 36-Year-Old Man (He/Him) with Pulmonary Tuberculosis

A 36-year-old man (he/him) with pulmonary tuberculosis. There is an opacification of a portion of the left upper lung in association with a cavity, findings consistent with pulmonary tuberculosis. Also, there is an infiltrate in the right lung. The extent of his disease raises the specter that he has underlying HIV/AIDS. (Reproduced with permission from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2019.)

In cases of active tuberculosis, treatment of people with HIV is similar to that of people without HIV. However, rifampin should not be given to patients receiving a boosted protease inhibitor (PI) regimen. In these cases, rifabutin may be substituted, but it may require dosing modifications depending on the antiretroviral regimen. Tenofovir alafenamide should not be used with rifampin and should be substituted for tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). Dolutegravir may be given with rifampin but should be dose adjusted to twice daily. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis has been a major problem in several metropolitan areas of the developed world, and cases of "extremely resistant" tuberculosis in patients with HIV are an important global concern. Nonadherence with prescribed antituberculous medications is a major risk factor. Several of the reported outbreaks appear to implicate nosocomial spread. The emergence of medication resistance makes it essential that antibiotic sensitivities be performed on all positive cultures. Medication therapy should be individualized. Patients with multidrug-resistant (MDR) M tuberculosis infection should receive at least three medications to which their organism is sensitive. The rise of MDR TB and extensively resistant TB in Eastern Europe and Russia has prompted increasing use of bedaquiline/pretomanid/linezolid-based regimens.

Atypical mycobacteria can cause pulmonary disease in patients with AIDS with or without preexisting lung disease and responds variably to treatment. Distinguishing between M tuberculosis and atypical mycobacteria is typically accomplished using M tuberculosis nucleic acid amplification (NAA) if available, which can also identify rifampin resistance rapidly, or via culture. DNA probes allow for presumptive identification usually within days of a positive culture. Definitive species identification for nontuberculous mycobacteria typically requires culture of sputum specimens. While awaiting definitive diagnosis, if clinical suspicion is high, clinicians should err on the side of treating patients as if they have M tuberculosis infection. Clinicians may wait for definitive diagnosis if the person is smear-negative for acid-fast bacilli, M tuberculosis NAA negative, clinically stable, and not living in a communal setting. It is important to note that isolated M avium complex pneumonia is relatively uncommon in AIDS, so diagnostic work-up for unexplained pneumonia should continue if preexisting structural lung disease is not present.

BlancFXet al; STATIS ANRS 12290 Trial Team. Systematic or test-guided treatment for tuberculosis in HIV-infected adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2397. [PMID: 32558469] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Provisional CDC guidance for the use of pretomanid as part of a regimen [bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid (BPaL)] to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis disease. 2022 Feb. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/drtb/bpal/default.htm KerkhoffADet al. VirtualCROI 2020: tuberculosis and coinfections in HIV infection. Top Antivir Med. 2020;28:455. [PMID: 32886465] LapinelNCet al. Prevalence of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in HIV-infected patients admitted to hospital with pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis.2019;23:491. [PMID: 31064629] |

People with HIV prior to COVID-19 vaccines have a greater propensity for severe COVID-19 disease, in part related to higher rates of medical comorbidities (eg, CVD, lung disease, long-term smoking), although low CD4 counts and virologic nonsuppression also portend higher risk. People with HIV should be considered a priority group for preventive strategies, including boosting the initial vaccination series, and early treatment approaches with antivirals.

People with HIV should not alter their ART regimens or add medications for the purpose of possibly preventing or treating SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, tenofovir-based regimens for HIV may be protective against SARS-CoV-2, as seen in large observational studies. With ongoing vaccination and natural infection, population immunity has risen in all groups, including people living with HIV. When COVID-19 is diagnosed in a person with HIV, ART should be continued, even if Paxlovid is initiated, since the course of the latter is only 5 days, despite the potential for drug-drug interactions.

Isolation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid occurs commonly in patients with AIDS but does not establish a definitive diagnosis, with CMV pneumonitis remaining a very rare opportunistic infection among people with AIDS. Diagnosis of CMV pneumonitis typically requires biopsy; response to treatment is poor. Histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcal disease as well as more common respiratory viral infections should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of unexplained pulmonary infiltrates.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV and COVID-19 Basics. Updated 2023 Sept 12. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/covid-19.html. LiGet al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes in men with HIV. AIDS. 2022;36:1689. [PMID: 35848570] TesorieroJMet al. COVID-19 outcomes among persons living with or without diagnosed HIV infection in New York State. JAMA Netw Open.2021;4:e2037069. [PMID: 33533933] US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for COVID-19 and persons with HIV. Updated 2022 Feb 22. http://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/guidance-covid-19-and-people-hiv/guidance-covid-19-and-people-hiv Western Cape Department of Health in collaboration with the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, South Africa. Risk factors for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) death in a population cohort study from the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis.2021;73:e2005. [PMID: 32860699] |

3. Noninfectious Pulmonary Diseases

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis may mimic Pneumocystis pneumonia. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis seen in lung biopsies has a variable clinical course. Typically, these patients present with several months of mild cough and dyspnea; CXRs show interstitial infiltrates. Performed rarely, transbronchial biopsies demonstrate interstitial inflammation ranging from an intense lymphocytic infiltration (consistent with lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis) to a mild mononuclear inflammation.

MarcusJLet al. Comparison of overall and comorbidity-free life expectancy between insured adults with and without HIV infection, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e207954. [PMID: 32539152] |

4. Sinusitis

Chronic sinusitis can be a frustrating problem for people with HIV. Symptoms include sinus congestion and discharge, headache, and fever. Some patients may have radiographic evidence of sinus disease on sinus CT scan in the absence of significant symptoms.

BaoSet al. Otorhinolaryngological profile and surgical intervention in patients with HIV/AIDS. Sci Rep.2018;8:12045. [PMID: 30104657] NabetCet al. Histoplasma capsulatum causing sinusitis: a case report in French Guiana and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:595. [PMID: 30477434] |

C. Central Nervous System Disease

CNS disease in people with HIV can be divided into intracerebral space-occupying lesions, encephalopathy, meningitis, and spinal cord processes. Many of these complications have declined markedly in prevalence in the era of effective ART. Cognitive declines, however, may be more common in persons with HIV, especially as they age (older than 50 years), even among those who remain virologically suppressed.

StephensRJet al. Central nervous system infections in the immunocompromised adult presenting to the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2021;39:101. [PMID: 33218652] |

1. Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis used to be one of the most common CNS space-occupying lesion in people with HIV. Headache, focal neurologic deficits, seizures, or altered mental status may be presenting symptoms. The diagnosis is usually made presumptively based on the characteristic appearance of cerebral imaging studies in an individual known to be seropositive for Toxoplasma. Typically, toxoplasmosis appears as multiple contrast-enhancing lesions on CT scan that do not reduce on diffusion on MRI scan. Lesions tend to be peripheral, with a predilection for the basal ganglia.

Single lesions are atypical of toxoplasmosis. When a single lesion has been detected by CT scanning, MRI scanning may reveal multiple lesions because of its greater sensitivity. If a patient has a single lesion on MRI and is neurologically stable, clinicians may pursue a 2-week empiric trial of toxoplasmosis therapy. A repeat scan should be performed at 2 weeks. If the lesion has not diminished in size, biopsy of the lesion should be performed. A positive Toxoplasma serologic test does not confirm the diagnosis because many people with HIV have detectable titers without having active disease. Conversely, less than 3% of patients with toxoplasmosis have negative titers. Therefore, negative Toxoplasma titers in a patient with HIV infection and a space-occupying lesion should be a cause for aggressively pursuing an alternative diagnosis. The preferred treatment of toxoplasmosis is with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine (Table 33-3. Treatment of AIDS-Related Opportunistic Infections and Malignancies (Listed in Alphabetical Order)). If pyrimethamine is not available, patients can be treated with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

VidalJE.HIV-related cerebral toxoplasmosis revisited: current concepts and controversies of an old disease. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2019;18:2325958219867315. [PMID: 31429353] |

2. Cns Lymphoma

Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the second most common CNS space-occupying lesion in people with HIV. Symptoms are similar to those with toxoplasmosis. While imaging techniques cannot distinguish these two diseases with certainty, lymphoma more often is solitary. Other less common lesions should be suspected if there is preceding bacteremia, tuberculosis risk factors, fungemia, or injection drug use. These include bacterial abscesses, cryptococcomas, tuberculomas, and Nocardia lesions.

Stereotactic brain biopsy should be strongly considered if lesions are solitary or do not respond to toxoplasmosis treatment, especially if they are easily accessible. Diagnosis of lymphoma is important because many patients benefit from treatment (radiation therapy). A positive PCR assay of CSF for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA is consistent with a diagnosis of lymphoma; a PCR for EBV DNA in CSF is 100% sensitive and 98.5% specific for AIDS-associated primary CNS lymphoma, making it useful as a diagnostic tumor marker.

KimaniSMet al. Epidemiology of haematological malignancies in people living with HIV. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e641. [PMID: 32791045] MarcusCet al. Imaging in differentiating cerebral toxoplasmosis and primary CNS lymphoma with special focus on FDG PET/CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:157. [PMID: 33112669] |

3. HIV-Associated Dementia and Neurocognitive Disorders

Patients with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders, including dementia typically have difficulty with cognitive tasks (eg, memory, attention), exhibit diminished motor function, and have emotional or behavioral problems. Patients may first notice a deterioration in their handwriting. The manifestations of cognitive impairment or dementia may wax and wane, with persons exhibiting periods of lucidity and confusion over the course of a day. The diagnosis of HIV-associated dementia most commonly occurs in untreated patients with advanced HIV infection, and is one of exclusion based on a brain imaging study and on spinal fluid analysis that excludes other pathogens. Neuropsychiatric testing is helpful in distinguishing patients with dementia from those with depression. Many patients improve with ART. However, slowly progressive neurocognitive deficits may still develop in patients taking ART as they age.

Metabolic abnormalities may also cause changes in mental status: hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, hypoxia, and drug overdose are important considerations in this population. Other less common infectious causes of encephalopathy include progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (discussed below), CMV, syphilis, and herpes simplex encephalitis.

AvedissianSNet al. Pharmacologic approaches to HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2020;54:102. [PMID: 33049585] RoscaECet al. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neuropsychol Rev.2019;29:313. [PMID: 31440882] |

4. Cryptococcal Meningitis

Cryptococcal meningitis typically presents with fever and headache. Less than 20% of patients have meningismus. Diagnosis is based on a positive latex agglutination test of serum or CSF that detects cryptococcal antigen (or "CrAg") or positive culture of spinal fluid for Cryptococcus. Approximately 99% of patients with cryptococcal meningitis have a positive serum CrAg. Thus, a negative serum CrAg test makes a diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis unlikely and can be useful in the initial evaluation of a patient with headache, fever, and normal mental status. Treatment has three phases: induction, consolidation, and maintenance. Induction treatment is given for a minimum of 2 weeks plus evidence of clinical improvement and a negative CSF culture on repeat lumbar puncture. The preferred induction treatment is liposomal amphotericin with flucytosine (Table 33-3. Treatment of AIDS-Related Opportunistic Infections and Malignancies (Listed in Alphabetical Order)), followed by an oral fluconazole treatment, and then secondary prophylaxis. Prophylaxis can be stopped if the patient is asymptomatic, has a CD4 cell count of greater than 100/mcL for at least 3 months, and has suppressed viral load on ART. Of note, a 2022 study showed that an alternative induction regimen of just a single dose of liposomal amphotericin B with 14 days of flucytosine and concomitant fluconazole was noninferior to the longer course of amphotericin B; this can be considered an alternative approach in resource-limited settings or if liposomal amphotericin B is not tolerated.

Boyer-ChammardTet al. Recent advances in managing HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. F1000Res. 2019;8:743. [PMID: 31275560] JarvisJNet al; Ambition Study Group. Single-dose liposomal amphotericin B treatment for cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med.2022;386:1109. [PMID: 35320642] LawrenceDS.Emerging concepts in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2019;32:16. [PMID: 30507673] MoengLRet al. HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: A review of novel short-course and oral therapies. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2020;12:422-437. SkipperCet al. Diagnosis and management of central nervous system cryptococcal infections in HIV-infected adults. J Fungi (Basel). 2019;5:E65. [PMID: 31330959] TenfordeMWet al. Treatment for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7:CD005647. [PMID: 30045416] |

5. Meningococcal Meningitis

People with HIV infection are at increased risk for bacterial meningococcal disease. Treatment is the same as in people without infection. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends the meningococcal conjugate vaccine routinely (serogroups A, C, W, and Y) for all persons aged 2 months or older with HIV infection. In settings of meningococcal outbreaks, the meningococcal B vaccine may be administered to adolescents and young adults with HIV, not necessarily all patients with HIV, for short-term protection against most strains of serogroup B meningococcal disease. Routine administration of meningococcal B vaccine to patients with HIV, however, is not indicated.

BozioCHet al. Meningococcal disease surveillance in men who have sex with men-United States, 2015-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2018;67:1060. [PMID: 30260947] National Institutes of Health (NIH). HIVinfo. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. 2023 Jan 11. http://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/immunizations |

6. HIV Meningitis and HIV Myelopathy

HIV meningitis, characterized by lymphocytic pleocytosis of the spinal fluid with negative culture, is common early in HIV infection. Spinal cord function may also be impaired in individuals with HIV infection. HIV myelopathy presents with leg weakness and incontinence. Spastic paraparesis and sensory ataxia are seen on neurologic examination. Myelopathy is usually a late manifestation of HIV disease, and most patients will have concomitant HIV encephalopathy. Pathologic evaluation of the spinal cord reveals vacuolation of white matter. Because HIV myelopathy is a diagnosis of exclusion, symptoms suggestive of myelopathy should be evaluated by lumbar puncture to rule out CMV polyradiculopathy (described below) and an MRI or CT scan to exclude epidural lymphoma.

LeffertJet al. HIV-vacuolar myelopathy: an unusual early presentation in HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2021;32:205. [PMID: 33323068] LevinSNet al. HIV and spinal cord disease. Handb Clin Neurol.2018;152:213. [PMID: 29604979] |

7. Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML)

PML is a viral infection (with the JC polyomavirus) of the white matter of the brain seen in patients with very advanced HIV infection. It typically results in focal neurologic deficits such as aphasia, hemiparesis, and cortical blindness. Imaging studies are strongly suggestive of the diagnosis if they show non-enhancing white matter lesions without mass effect; the diagnosis is verified by JC virus positivity via PCR in the CSF. Patients can stabilize or improve after ART initiation; there is no other treatment. In the setting of wide-scale ART and because PML occurs at very low CD4 counts, the prevalence of this condition is rare.

AbrãoCOet al. AIDS-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;54:e02522020. [PMID: 33338109] CorteseIet al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and the spectrum of JC virus-related disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17:37. [PMID: 33219338] |

D. Peripheral Nervous System

An inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy similar to Guillain-Barre syndrome can occur in people with HIV, usually prior to frank immunodeficiency. The syndrome in many cases improves with plasmapheresis, supporting an autoimmune basis of the disease. CMV can cause an ascending polyradiculopathy characterized by lower extremity weakness and a neutrophilic pleocytosis on spinal fluid analysis with a negative bacterial culture. Transverse myelitis can be seen with herpes zoster or CMV.

Peripheral neuropathy is common among people with HIV. Patients typically complain of numbness, tingling, and pain in the lower extremities. Symptoms are disproportionate to findings on gross sensory and motor evaluation. Beyond HIV infection itself, the most common cause is prior ART with a thymidine analog, such as stavudine or didanosine (although both are no longer available in the United States). Unfortunately, medication-induced neuropathy was not always reversed when the offending agent was discontinued. Patients with advanced disease may also develop peripheral neuropathy; in some cases, it occurs among those with suppressed viral loads. In many patients, the neuropathy improves after persistent virologic suppression is achieved. Evaluation should rule out other causes of sensory neuropathy such as alcohol use disorder, thyroid disease, diabetes, vitamin B12 deficiency, and syphilis.

JulianTet al. Human immunodeficiency virus-related peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:1420. [PMID: 33226721] |

E. Rheumatologic and Bone Manifestations

Arthritis, involving single or multiple joints, with or without effusion, has been commonly noted in people with HIV. Involvement of large joints is most common. Although the cause of HIV-related arthritis is unknown, most patients will respond to NSAIDs. Patients with a sizable effusion, especially if the joint is warm or erythematous, should have the joint aspirated, followed by culture of the fluid to rule out suppurative arthritis as well as fungal and mycobacterial disease.

Several rheumatologic syndromes, including reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, sicca syndrome, and SLE, are reported in people with HIV (see Part 22). However, it is unclear if the prevalence is greater than in the general population. Cases of avascular necrosis of the femoral heads have been reported sporadically, generally in the setting of advanced disease with long-standing infection and in patients receiving long-term ART. The etiology is not clear but is probably multifactorial in nature.

Osteoporosis and osteopenia appear to be more common in people with HIV with chronic infection and is associated with long-term use of TDF and PI-based ART. Vitamin D deficiency appears to be quite common among people with HIV and monitoring vitamin D levels and instituting replacement therapy for detected deficiency are recommended. Bone mineral density scans for postmenopausal women with HIV and men 50 years old or older are also recommended.

ThomsenMTet al. Prevalence of and risk factors for low bone mineral density assessed by quantitative computed tomography in people living with HIV and uninfected controls. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;83:165. [PMID: 31929404] VegaLEet al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV)-associated rheumatic manifestations in the pre- and post-HAART eras. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:2515. [PMID: 32297034] |

F. Myopathy

Myopathies are infrequent in the era of effective ART but can be related to either HIV infection or ART, particularly with use of the older agent zidovudine (azidothymidine [AZT]). Proximal muscle weakness is typical, and patients may have varying degrees of muscle tenderness. Given its long-term toxicities, zidovudine is no longer recommended when alternative treatments are available. Integrase strand transferase inhibitors rarely have been associated with creatine phosphokinase elevations and myopathy.

KakuMet al. Neuromuscular complications of HIV infection. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;152:201. [PMID: 29604977] PriorDEet al. Neuromuscular diseases associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Neurol Sci. 2018;387:27. [PMID: 29571868] |

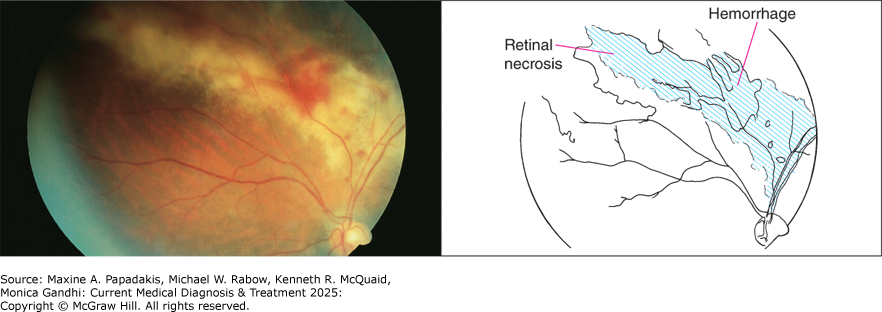

G. Retinitis

In people with HIV, complaints of visual changes must be evaluated immediately by an ophthalmologist familiar with the manifestations of HIV disease. CMV retinitis, characterized by perivascular hemorrhages and white fluffy exudates, is the most common retinal infection in patients with AIDS, usually with CD4 counts less than 50 cells/mcL, and can be rapidly progressive (Figure 33-4). In contrast, cotton wool spots, which also are common in people with HIV, are benign, remit spontaneously, and appear as small indistinct white spots without exudation or hemorrhage. Ocular syphilis also should be considered, with the incidence of syphilis rising over time among people with HIV. Other rare retinal processes include other herpesvirus infections or toxoplasmosis. Choice of treatment for CMV retinitis (Table 33-3. Treatment of AIDS-Related Opportunistic Infections and Malignancies (Listed in Alphabetical Order)) depends on severity and location of lesions, as well as the patient's overall condition and circumstances.

Figure 33-4. CMV Retinitis

CMV retinitis. Retina has classic "pizza pie" or "cheese and ketchup" appearance, with hemorrhages and dirty white, granular appearing retinal necrosis adjacent to major vessels (see diagrammatic map). (Photo contributed by Richard E. Wyszynski, MD. Used, with permission, from Richard E. Wyszynski, MD, in Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, Thurman RJ. The Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 5th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2021.)

BallardBet al. CMV retinitis. EyeWiki. 2020 Oct 22. http://eyewiki.org/CMV_Retinitis#General_treatment HeidenDet al. Active cytomegalovirus retinitis after the start of antiretroviral therapy. Br J Ophthalmol.2019;103:157. [PMID: 30196272] TangYet al. Clinical features of cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV infected patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:136. [PMID: 32318357] WonsJet al. HIV-induced retinitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28:1259. [PMID: 32966142] |

H. Oral Lesions

eFigure 33-1A. Pseudomembranous Form of Oral Candidiasis is the Most Common; the White Plaques over the Hard Palate Raise the Suspicion of Underlying HIV/AIDS

Pseudomembranous form of oral candidiasis is the most common; the white plaques over the hard palate raise the suspicion of underlying HIV/AIDS. They can be scraped off with a tongue blade, placed on a slide, and mixed with potassium hydroxide solution to make the diagnosis of Candida albicans (see eFigure 33-1C). (Reproduced with permission from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr., Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

eFigure 33-1B. This Man with HIV-AIDS Has the (Less Common) Erythematous Form of Oral Candidiasis

This man with HIV-AIDS has the (less common) erythematous form of oral candidiasis. The patient also has perlèche or angular cheilitis (Candida infection at the corners of the mouth). (Reproduced with permission from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr., Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

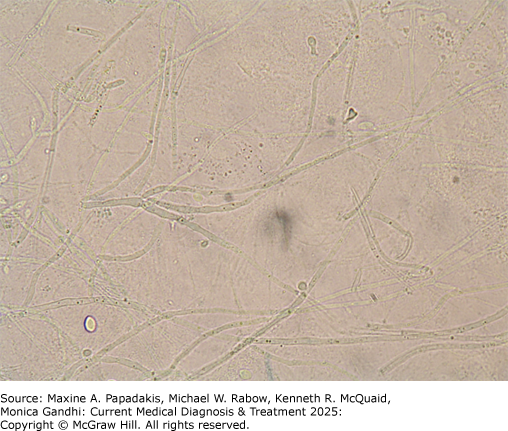

eFigure 33-1C. Photomicrograph of Candida Albicans on Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) Preparation

Photomicrograph of Candida albicans on potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. When an oral candidiasis lesion is scraped, added to a slide with KOH under a cover slip, and examined under low power microscopy, the pseudohyphae and/or budding yeast forms of C albicans are seen. (Reproduced with permission from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr., Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

Oral hairy leukoplakia is caused by the Epstein-Barr virus. The lesion is not usually troubling to patients and sometimes regresses spontaneously. Hairy leukoplakia is commonly seen as a white lesion on the lateral aspect of the tongue. It may be flat or slightly raised, is usually corrugated, and has vertical parallel lines with fine or thick ("hairy") projections (see Figure 8-6). Unlike oral candidiasis, this lesion cannot be scraped off, a distinguishing feature in the physical examination.

The presence of oral candidiasis or hairy leukoplakia is significant for several reasons. First, these lesions are highly suggestive of HIV infection in patients who have no other obvious cause of immunodeficiency. Second, several studies have indicated that patients with candidiasis have a high rate of progression to AIDS even with statistical adjustment for CD4 count.

Gingival disease is common in people with HIV and is thought to be due to an overgrowth of microorganisms. Aphthous ulcers are painful and may interfere with eating.

Other lesions seen in the mouths of people with HIV include Kaposi sarcoma (usually on the hard palate) and oral warts.

Gingival disease usually responds to professional dental cleaning and chlorhexidine rinses. A particularly aggressive gingivitis or periodontitis will develop in some people with HIV; these patients should be given antibiotics that cover anaerobic oral flora (eg, metronidazole, 250 mg four times a day for 4 or 5 days) and referred to oral surgeons with experience with these entities.

Aphthous ulcers (eFigure 33-2A; eFigure 33-2B; eFigure 33-2C) can be treated with fluocinonide (0.05% ointment mixed 1:1 with plain Orabase and applied six times a day to the ulcer). For lesions that are difficult to reach, patients should use dexamethasone swishes (0.5 mg in 5 mL elixir three times a day). The pain of the ulcers can be relieved with an anesthetic spray (10% lidocaine).

eFigure 33-2A. Recurrent Oral Aphthous Stomatitis

Recurrent oral aphthous stomatitis. A 58-year-old man presented with a 1-year history of recurrent painful sores in his mouth. He had lost 20 pounds over the year because it hurt so much to eat. The ulcers, which had a red base and were covered with a central white membrane, occurred in different locations-on his tongue, gums, inner lips, and buccal mucosa (shown here). HIV-AIDS is an underlying systemic disease that can be documented on work-up of such patients. (Used, with permission, from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

eFigure 33-2B. Two Aphthous Ulcers on the Tongue

Two aphthous ulcers on the tongue. (Reproduced with permission from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr., Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

eFigure 33-2C. Minor Aphthous Ulcer Occurring on the Buccal Mucosa

Minor aphthous ulcer occurring on the buccal mucosa. (Reproduced with permission from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr., Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

IndrastitiRKet al. Oral manifestations of HIV: can they be an indicator of disease severity? (A systematic review). Oral Dis. 2020;26:133. [PMID: 32862546] TappuniAR.The global changing pattern of the oral manifestations of HIV. Oral Dis. 2020;26:22. [PMID: 32862536] |

I. Gastrointestinal Manifestations

1. Candidal and other Esophagitis

(See also Part 17.) Esophageal candidiasis is a common AIDS complication. In a patient with characteristic symptoms, empiric antifungal treatment is begun with fluconazole (200-400 mg orally daily for 14-21 days). Improvement in symptoms should be apparent within 1-2 days of antifungal treatment. If there is no improvement, fungal culture to exclude fluconazole resistance, and further evaluation to identify other causes of esophagitis (herpes simplex, CMV) is recommended.

HoverstenPet al. Risk factors, endoscopic features, and clinical outcomes of cytomegalovirus esophagitis based on a 10-year analysis at a single center. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:736. [PMID: 31077832] MohamedAAet al. Diagnosis and treatment of esophageal candidiasis: current updates. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol.2019;2019:3585136. [PMID: 31772927] |

2. Hepatic Disease

Hepatitis C is more virulent in patients with HIV and should be treated using HCV direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) (see Table 18-6). Prior to treatment, the patient's HCV viral load and HCV genotype should be determined. Pan-genotypic regimens such as glecaprevir/pibrentasvir are increasingly used. Because new DAAs are available and because HCV treatment is a rapidly changing field, clinicians should check the guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (ASLD)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (http://www.hcvguidelines.org/) to see the latest recommended regimens (see also Tables 18-6 and 18-7).

Although the recommended regimens are the same for people with HIV, potential drug interactions with ART may complicate treatment. Clinicians should check the guidelines of the AASLD/IDSA and US Department of Health and Human Services or the guidelines of the University of Liverpool to determine interactions between proposed hepatitis C regimen and HIV regimen. Ritonavir-containing protease inhibitor regimens for HIV are the most likely to cause drug-drug interactions.

Liver transplants have been performed successfully in people with HIV. This strategy is most likely to be successful in persons who have CD4 counts greater than 100 cells/mcL and nondetectable viral loads.

ButiM.Hepatitis D virus: more attention needed. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:556. [PMID: 35883011] LakeJEet al. Expert panel review on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in persons with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:256. [PMID: 33069882] PatelSVet al. Real-world efficacy of direct acting antiviral therapies in patients with HIV/HCV. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0228847. [PMID: 32053682] University of Liverpool. HEP drug interactions. http://www.hep-druginteractions.org US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents, August 28, 2020. http://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infection/whats-new-guidelines WylesDL.Antiretroviral effects on HBV/HIV co-infection and the natural history of liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2019;23:473. [PMID: 31266621] |

3. Biliary Disease

Cholecystitis presents with manifestations similar to those seen in immunocompetent hosts but is more likely to be acalculous. Sclerosing cholangitis and papillary stenosis have also been reported in people with HIV. Typically, the syndrome presents with severe nausea, vomiting, and right upper quadrant pain. Liver enzymes generally show alkaline phosphatase elevations disproportionate to elevation of the aminotransferases. Although dilated ducts can be seen on ultrasound, the diagnosis is made by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, which reveals intraluminal irregularities of the proximal intrahepatic ducts with "pruning" of the terminal ductal branches. Stenosis of the distal common bile duct at the papilla is commonly seen. CMV, Cryptosporidium, and microsporidia are thought to play inciting roles in this syndrome, but these conditions are rarely seen unless the patient is experiencing very advanced HIV-related immunodeficiency.

NaseerMet al. Epidemiology, determinants, and management of AIDS cholangiopathy: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:767. [PMID: 29467548] VelásquezJNet al. Multimethodological approach to gastrointestinal microsporidiosis in HIV-infected patients. Acta Parasitol. 2019;64:658. [PMID: 31286356] |

4. Enterocolitis

Because of the wide range of agents known to cause enterocolitis, a stool culture and multiple stool examinations for ova and parasites (including modified acid-fast staining for Cryptosporidium and Giardia antigen testing) should be performed. Patients who have Cryptosporidium in one stool with improvement in symptoms in less than 1 month should not be considered to have AIDS, as Cryptosporidium is a cause of self-limited diarrhea in HIV-negative persons. More commonly, people with HIV with subsequent immunodeficiency with Cryptosporidium infection have persistent enterocolitis with profuse watery diarrhea.

Patients with a negative stool examination and persistent symptoms should be evaluated with colonoscopy and biopsy. Patients whose symptoms last longer than 1 month with no identified cause of diarrhea are considered to have a presumptive diagnosis of HIV enteropathy. Patients may respond to ART initiation, antimotility agents, or crofelemer (an antidiarrheal agent).

SparksBSet al. Treatment of Cryptosporidium: what we know, gaps, and the way forward. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2015;2:181. [PMID: 26568906] WangRJet al. Widespread occurrence of Cryptosporidium infections in patients with HIV/AIDS: epidemiology, clinical feature, diagnosis, and therapy. Acta Trop. 2018;187:257. [PMID: 30118699] WangZDet al. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium, microsporidia and Isospora infection in HIV-infected people: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:28. [PMID: 29316950] |

5. Other Disorders

Two other important GI abnormalities in people with advanced AIDS are gastropathy and malabsorption. It has been documented that some people with HIV do not produce normal levels of stomach acid and therefore are unable to absorb medications that require an acid medium. This decreased acid production may explain, in part, the susceptibility of people with HIV to Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella, all of which are sensitive to acid concentration. There is no evidence that Helicobacter pylori is more common in people with HIV.

A malabsorption syndrome occurs commonly in patients with AIDS. It can be due to infection of the small bowel with M avium complex, Cryptosporidium, or microsporidia.

HallVP.Common gastrointestinal complications associated with human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS: an overview. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2018;30:101. [PMID: 29413205] |

J. Endocrinologic Manifestations

Hypogonadism is probably the most common endocrinologic abnormality in men with HIV. The adrenal gland is also a commonly afflicted endocrine gland in patients with AIDS, either from HIV, TB, CMV, histoplasmosis or other mycobacterial organisms. Abnormalities demonstrated on autopsy include infection, especially with CMV and M avium complex (ie, those with severe immunocompromise), infiltration with Kaposi sarcoma, and injury from hemorrhage and presumed autoimmunity. The prevalence of clinically significant adrenal insufficiency is low. Patients with suggestive symptoms should undergo a cosyntropin stimulation test.

Although frank deficiency of cortisol is rare, an isolated defect in mineralocorticoid metabolism may lead to salt-wasting and hyperkalemia. Such patients should be treated with fludrocortisone (0.1-0.2 mg orally daily). Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole also may cause hyperkalemia through its effects on the distal nephron, so it should be used with caution.

Patients with AIDS appear to have abnormalities of thyroid function tests different from those of patients with other chronic diseases. Patients with AIDS have been shown to have high levels of triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4), and thyroid-binding globulin and low levels of reverse triiodothyronine (rT3). The causes and clinical significance of these abnormalities are unknown and generally improve with ART initiation.

MaffezzoniFet al. Hypogonadism and bone health in men with HIV. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e782. [PMID: 33128905] PezzaioliLCet al. The importance of SHBG and calculated free testosterone for the diagnosis of symptomatic hypogonadism in HIV-infected men: a single-centre real-life experience. Infection. 2021;49:295. [PMID: 33289905] SantiDet al. The prevalence of hypogonadism and the effectiveness of androgen administration on body composition in HIV-infected men: a meta-analysis. Cells. 2021;10:2067. [PMID: 34440836] ZaidDet al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and the endocrine system. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2019;34:95. [PMID: 31257738] |

K. Skin Manifestations

The skin manifestations that commonly develop in people with HIV can be grouped into viral, bacterial, fungal, neoplastic, and nonspecific dermatitides.

CoatesSJet al. What's new in HIV dermatology?F1000Res. 2019;8:980. [PMID: 31297183] |

1. Viral Dermatitides

Figure 33-5. Herpes Simplex Viral Skin Infection, Frequently Found in Men (He/Him) with HIV

Herpes simplex viral skin infection, frequently found in men (he/him) with HIV. Shown are grouped vesicles typical of herpes simplex on the penis, with both intact vesicles of initial eruption and visible crusts of resolving lesions. (Reproduced, with permission, from Eric Kraus, MD, in: Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H. The Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2019.)

eFigure 33-3. Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster. A painful vesicular eruption developed over the right forehead in this 44-year-old with HIV infection. Herpes zoster was diagnosed clinically and confirmed by a positive direct fluorescent antibody test on fluid from one of the vesicles. (Reproduced with permission from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr., Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

HarbeckeRet al. Herpes zoster vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2021;224:S429. [PMID: 34590136] |

eFigure 33-4. Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum. Close-up of a molluscum contagiosum lesion showing a dome-shaped pearly papule with a characteristic umbilicated center. (Reproduced with permission from Richard P. Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr., Chumley H. The Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2019.)

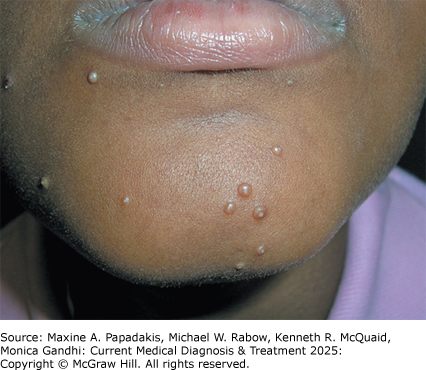

Figure 33-6. Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum. Extensive molluscum contagiosum lesions on the face of a young person, suggestive of HIV. (Reproduced with permission from Richard P. Usatine, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2019.)

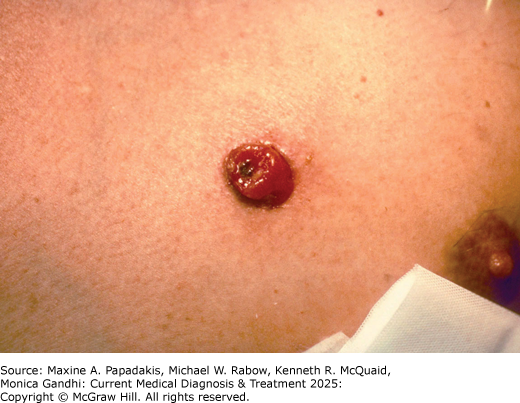

In the 2022 outbreak, a higher rate of mpox cases occurred among people with HIV (~40% of all cases), although it is unclear if this due to greater susceptibility to the virus, the disproportionate outbreak among MSM, proclivity toward orthopoxviruses with HIV infection, or other factors. Risk factors for greater severity of mpox disease in HIV include having a CD4+ T-cell count less than 200 cells/mcL, although some studies suggest greater rash burden among people with HIV regardless of T-cell count. Patients may first develop fevers, chills, and myalgias, which are then followed by the characteristic rash, which begins as small macules that then evolve into papules, vesicles, and pseudo-pustules filled with cell debris rather than pus. The lesions eventually crust over and fall off approximately 7-14 days after the beginning of the rash. The rash is often painful and, in the most recent outbreak, frequently occurs in the anogenital or perioral areas. Proctitis occurring with the disease may or may not be associated with anorectal lesions. Ocular lesions may occur, and coalescence of lesions may lead to bacterial superinfection. Cases of encephalitis, sepsis, myocarditis, and bowel obstruction have been described, but are rare. Diagnosis is made by orthopoxvirus DNA PCR performed on swab of the lesions. Most patients will recover with supportive care, although tecovirimat therapy can be considered for individuals with or at risk for severe disease, including uncontrolled HIV, those with lesions in the eyes, confluent lesions, severe oral lesions limiting oral intake, or systemic life-threatening disease. Evidence from RCTs on tecovirimat for mpox is not yet available, although data from retrospective series suggest the treatment is well tolerated. A modified vaccinia vaccine (called Modified Vaccinia Ankara [MVA] or Jynneos vaccine) was the mainstay of prevention during the mpox global outbreak and is safe for people with HIV. Anyone with risk factors for mpox or who have had a recent exposure should be vaccinated. See also Part 34.

Allan-BlitzLT, GandhiMet al. A position statement on Mpox as a sexually transmitted disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76:1508. [PMID: 36546646] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim clinical guidance for treatment of monkey pox. Updated 2022 Oct 31. http://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/treatment.html Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Severe manifestations of monkeypox among people who are immunocompromised due to HIV or other conditions. September 29, 2022. http://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2022/han00475.asp MurphyMet al. Non-HPV perianal and anorectal sexually transmitted viral infections. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32:340. [PMID: 31507343] World Health Organization (WHO). Mpox Outbreak 2022. http://www.who.int/emergencies/situations/monkeypox-oubreak-2022 World Health Organization (WHO). 2022 Mpox (monkeypox) outbreak: global trends. 2023 Feb 21. http://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/ |

2. Bacterial Dermatitides

HatlenTJet al. Staphylococcal skin and soft tissue infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2021;35:81. [PMID: 33303329] SabbaghPet al. The global and regional prevalence, burden, and risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in HIV-infected people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:323. [PMID: 30170767] |

eFigure 33-5. Bacillary Angiomatosis

Bacillary angiomatosis. Bacillary angiomatosis is a systemic infection caused by Bartonella species. Its cutaneous lesions appear as scattered papules and nodules (like the one shown here) or as abscesses. In people with HIV, bacillary angiomatosis most often occurs when the CD4 count is below 200/mcL. It can be treated with antibiotics. (Reproduced, with permission, from Usatine RP, Moy RL, Tobinick EL, Siegel DM. Skin Surgery: A Practical Guide. Mosby, 1998. Copyright © Elsevier.)

MantisJet al. Cat-scratch disease in an AIDS patient presenting with generalized lymphadenopathy: an unusual presentation with delayed diagnosis. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:906. [PMID: 30068900] DingFet al. Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of Bartonella infective endocarditis: an 8-year single-centre experience in the United States. Heart Lung Circ. 2022;31:350. [PMID: 34456130] |

3. Fungal Rashes

Moreno-CoutiñoGet al. Isolation of Malassezia spp. in HIV-positive patients with and without seborrheic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:527. [PMID: 31777352] WikramanayakeTCet al. Seborrheic dermatitis-looking beyond Malassezia. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28:991. [PMID: 31310695] |

L. HIV-Related Malignancies

Four cancers are included in the CDC classification of AIDS: Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, primary lymphoma of the brain, and invasive cervical carcinoma. Epidemiologic studies have shown that between 1973 and 1987, among single men in San Francisco, the risk of Kaposi sarcoma increased more than 5000-fold and the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma more than 10-fold. In the current treatment era, cancers not classified as AIDS-related, such as lung cancer, are being increasingly diagnosed in aging people with HIV despite optimal ART. Cohort studies suggest that adults with HIV are at increased risk for a variety of cancers compared with age-matched adults who do not have HIV. Mortality secondary to malignancies represents an increasing cause of death in people with HIV.

ChiaoEYet al. The effect of non-AIDS-defining cancers on people living with HIV. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:e240. [PMID: 34087151] HessolNAet al. Incidence of first and second primary cancers diagnosed among people with HIV, 1985-2013: a population-based, registry linkage study. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e647. [PMID: 30245004] PumpalovaYSet al. The impact of HIV on non-AIDS defining gastrointestinal malignancies: a review. Semin Oncol. 2021;48:226. [PMID: 34593219] VangipuramRet al. AIDS-associated malignancies. Cancer Treat Res. 2019;177:1. [PMID: 30523619] WangLet al. Lung cancer surgery in people living with HIV: an analysis of postoperative complications and long-term survival. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11:2146. [PMID: 32627360] |

1. Kaposi Sarcoma

eFigure 33-6. Kaposi Sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma. A 35-year-old man presented with several reddish-purple papular lesions on his elbow. When these were diagnosed on shave biopsy as Kaposi sarcoma (KS), he was tested and found to be positive for HIV. Systemic treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy and topical treatment with alitretinoin gel was started, and the KS lesions eventually resolved. (Used, with permission, from Heather Wickless, MD, in Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ Jr, Chumley H. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill, 2013.)

AlvesCGBet al. Clinical and laboratory profile of people living with HIV/AIDS with oral Kaposi sarcoma. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2021;37:870. [PMID: 34538064] Dalla PriaAet al. Recent advances in HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma. F1000Res. 2019;8:970. [PMID: 31297181] Gouveia-MoraesFet al. Conjunctival Kaposi's sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:e36. [PMID: 34525288] NgalamikaOet al. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV-associated cutaneous Kaposi's sarcoma: clinical, HIV-related, and sociodemographic predictors of outcome. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2021;37:368. [PMID: 33386064] |

2. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

KimaniSMet al. Epidemiology of haematological malignancies in people living with HIV. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e641. [PMID: 32791045] LillyAJet al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12:771. [PMID: 31352987] LurainKet al. Treatment of HIV-associated primary CNS lymphoma with antiretroviral therapy, rituximab, and high-dose methotrexate. Blood. 2020;136:2229. [PMID: 32609814] |

3. Hodgkin Disease

Although Hodgkin disease is not included as part of the CDC definition of AIDS, studies have found that HIV infection is associated with a fivefold increase in the incidence of Hodgkin disease. HIV-infected persons with Hodgkin disease are more likely to have mixed cellularity and lymphocyte depletion subtypes of Hodgkin disease and to seek medical attention at an advanced stage of disease.

PerriconeAJet al. Cytodiagnostic sensitivity of fine needle aspiration biopsy for Hodgkin's lymphoma is decreased in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Acta Cytol. 2019;63:352. [PMID: 31234174] ReAet al. HIV and lymphoma: from epidemiology to clinical management. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2019;11:e2019004. [PMID: 30671210] |

4. Anal Dysplasia and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

These lesions are generally a result of HPV infection and noted in people of all genders with HIV. Although many report a history of anal warts or have visible warts, a significant percentage have silent papillomavirus infection. Cytologic (using Papanicolaou smears) and papillomavirus DNA studies can be performed on specimens obtained by anal swab. Because of the risk of progression from dysplasia to cancer in patients with HIV, regular anal cytologic examinations or high-resolution anoscopy should be performed. An anal Papanicolaou smear is performed by rotating a moistened Dacron swab about 2 cm into the anal canal. The swab is immediately inserted into a cytology bottle. Some experts also recommend high-risk HPV PCR testing be included. In the large ANCHOR study, which involved nearly 4500 individuals with anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL), nine patients who were assigned to aggressive therapy (mostly office-based electrocautery) developed anal cancer compared with 21 of those in an active monitoring group (no treatment), representing a 57% decrease in relative risk of anal cancer over the median 25.8-month follow-up period. This pivotal study has changed care toward more aggressive screening for HGSIL and treatment to prevent progression to anal cancer among people with HIV.

HPV also plays a causative role in cervical dysplasia and carcinoma in women with HIV (discussed below).

ArensYet al. Risk of invasive anal cancer in HIV-infected patients with high-grade anal dysplasia: a population-based cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:934. [PMID: 30888979] CimicAet al. Importance of anal cytology and screening for anal dysplasia in individuals living with HIV with an emphasis on women. Cancer Cytopathol. 2019;127:407. [PMID: 31145557] GoddardSLet al; Study for the Prevention of Anal Cancer (SPANC) Research Team. Prevalence and association of perianal and intra-anal warts with composite high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions among gay and bisexual men: baseline data from the Study of the Prevention of Anal Cancer. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34:436. [PMID: 32955927] GonçalvesJCNet al. Accuracy of anal cytology for diagnosis of precursor lesions of anal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:112. [PMID: 30451747] PalefskyJMet al; ANCHOR Investigators Group. Treatment of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions to prevent anal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2273. [PMID: 35704479]. WangCJet al. HPV-associated anal cancer in the HIV/AIDS patient. Cancer Treat Res. 2019;177:183. [PMID: 30523625] |

M. Gynecologic Manifestations

Vaginal candidiasis, cervical dysplasia and neoplasia, and pelvic inflammatory disease are more common in women with HIV than in women without HIV. These manifestations also tend to be more severe when they occur in association with HIV infection. Therefore, women with HIV need frequent gynecologic care. Vaginal candidiasis may be treated with topical agents or a single dose of oral fluconazole (150 mg) (see Part 38). Recurrent vaginal candidiasis should be treated with fluconazole (100-200 mg) for at least 7 days. A single dose of fluconazole 150 mg to treat vaginal candidiasis is considered category C, although other uses are considered category D given the risk of rare birth defects.

Women with HIV have a six-fold increased risk of cervical cancer compared with women without HIV. Because of this finding, recommended screening for women with HIV is more extensive than for women without HIV (see Part 20). For women younger than age 30 years, a Papanicolaou smear should be performed within a year of the onset of sexual activity, but no later than age 21 years. If normal, Papanicolaou smears should be performed yearly. After three negative examinations, screening should be done every 3 years. HPV DNA testing of the cervical specimen is not recommended for women younger than age 30 years.

For women aged 30 years or older, screening should continue beyond age 65 years (unlike the general population). There are two accepted screening protocols: cytology alone and cytology with HPV DNA co-testing. A Papanicolaou smear is done when HIV is diagnosed and every 12 months thereafter, and after three negative smears, ongoing screening can be performed every 3 years. Alternatively, a Papanicolaou smear with co-testing for HPV DNA can be performed when HIV is diagnosed or starting when patients are 30 years old. If Papanicolaou smear is normal and HPV test is negative, then the next screening can be in 3 years.

The American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology recommends colposcopy for all results of HPV-positive ASC-US or higher, or LSIL or higher regardless of HPV status, among women with HIV. If HPV testing is not performed and the result is ASC-US, then cytology should be repeated in 6-12 months, with referral for colposcopy pursued if the repeat result is ASC-US or higher or if HPV positive. Treatment should follow the consensus guidelines in the references below.

While pelvic inflammatory disease appears to be more common in women with HIV, the bacteriology of this condition appears to be the same as among women without HIV. Women with HIV who have pelvic inflammatory disease should be treated with the same regimens as women without HIV (see Part 20).

CastlePEet al. Cervical cancer prevention and control in women living with human immunodeficiency virus. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:505. [PMID: 34499351] Perkinset al. ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines for Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors. 2020. http://www.asccp.org/management-guidelines StricklerHDet al. Primary HPV and molecular cervical cancer screening in US women living with HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:1529. [PMID: 32881999] |

N. Coronary Artery Disease

People with HIV are at higher risk for CAD than age- and sex-matched controls. Part of this increase in CAD may be due to residual inflammation that can occur despite ART. Results from the practice-changing 2023 REPRIEVE study indicate that statin treatment can benefit patients with HIV at lower ASCVD risk scores (2.5-5%). Some data suggest abacavir may be associated with MI, possibly related to increased platelet aggregation, although this association has not been found in all studies. Some of the risk appears to be due to HIV infection, independent of its therapy. It is important that clinicians pay close attention to this issue because MIs tend to present at a younger age in individuals with HIV than in individuals without HIV. People with HIV with symptoms of CAD such as chest pain or dyspnea should be rapidly evaluated. Clinicians should aggressively treat conditions that result in increased risk of heart disease, especially smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and sedentary lifestyle.

GrinspoonSKet al; REPRIEVE Investigators. Pitavastatin to prevent cardiovascular disease in HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:687. [PMID: 37486775] HsuePYet al. HIV infection and coronary heart disease: mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16:745. [PMID: 31182833] PatelAAet al. Coronary artery disease in patients with HIV infection: an update. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2021;21:411. [PMID: 33184766] |

O. Inflammatory Reactions (Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndromes)

With initiation of ART, some patients experience inflammatory reactions that appear to be associated with immune reconstitution as indicated by a rapid increase in CD4 count. These inflammatory reactions may present with generalized signs of fevers, sweats, and malaise with or without more localized manifestations that usually represent unusual presentations of opportunistic infections. For example, vitreitis has developed in patients with CMV retinitis after they have been treated with ART.

M avium can present as focal even suppurative lymphadenitis or granulomatous masses in patients receiving ART. Tuberculosis may paradoxically worsen with new or evolving pulmonary infiltrates and lymphadenopathy. PML and cryptococcal meningitis may also behave atypically. Clinicians should be alert to these syndromes, which are most often seen in patients who have initiated ART in the setting of advanced disease and who show rapid decreases in HIV viral load and increases in CD4 counts with treatment. The diagnosis of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is one of exclusion and can be made only after recurrence or new opportunistic infection has been ruled out as the cause of the clinical deterioration. Management of IRIS is conservative and supportive with use of corticosteroids only for severe reactions, with ART continued.

SeretiI.Immune reconstruction inflammatory syndrome in HIV infection: beyond what meets the eye. Top Antivir Med. 2020;27:106. [PMID: 32224502] SeretiIet al. Prospective international study of incidence and predictors of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and death in people living with human immunodeficiency virus and severe lymphopenia. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:652. [PMID: 31504347] |