Assessment and Monitoring

Assessment consists of an inspection of the infusion system, from the solution container down to the catheter insertion site (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S119). Assessment parameters include the infusate (e.g., clarity), the integrity of the system (e.g., secure connections, infusate/administration set not expired), and accurate flow rate. The PIVC is assessed for patency and the site and surrounding area are assessed for evidence of erythema, swelling or drainage, and the integrity of the dressing and securement. The site should be gently palpated to identify any induration or tenderness and always ask the patient if there is any pain or discomfort at the site. The INS (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S119) provides guidance for the frequency of assessing the short PIVC catheter as follows:

- At least every 4 hours for alert and oriented adult patients who are receiving nonirritant/nonvesicant infusions for any signs of problems such as pain, swelling, or redness at the site tissue

- Every 1 to 2 hours for critically ill patients, for adult patients who have cognitive/sensory deficits or who are receiving sedative-type medications and are unable to notify the nurse of any symptoms

- Every hour for pediatric and neonatal patients

- More often when infusing vesicant infusions

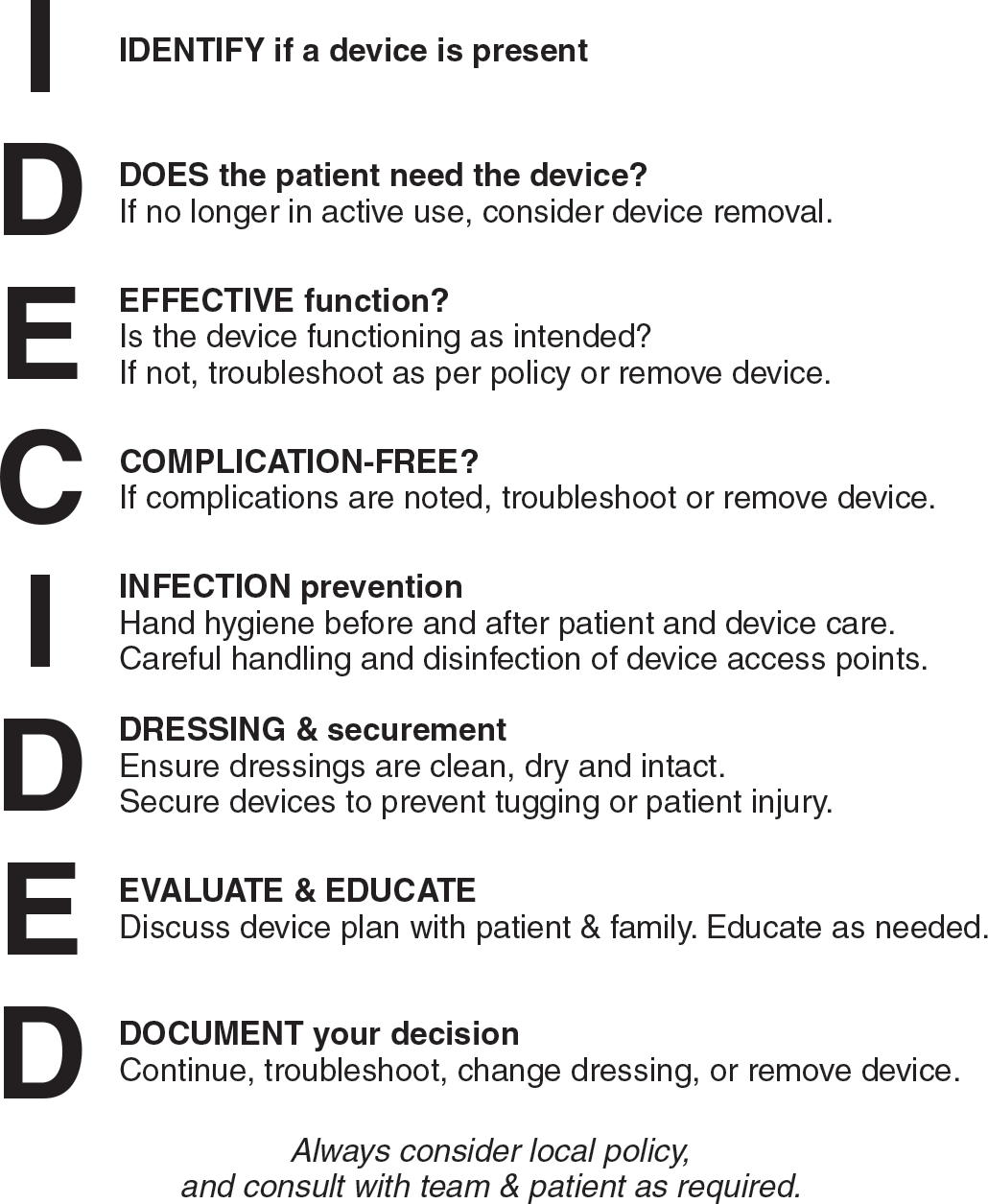

EBP. A checklist entitled I-DECIDED® is a relatively new valid and reliable PIVC assessment tool (Fig. 6-17) (Ray-Barruel et al., 2020). It is based on EBP guidelines and guides the nurse in assessment, use of infection prevention interventions, patient education, and documentation. It also guides appropriate and timely removal of the PIVC based upon PIVC need and/or presence of complications. This tool was tested in three Australian hospital medical-surgical units demonstrating both strong content validity and high interrater reliability. It can be downloaded and used in an institution and has been translated into numerous languages (Alliance for Vascular Access Teaching and Research [AVATAR, n.d.]).

Intermittent Infusions and Needleless Connectors

An NC is placed on the end of the short PIVC or midline catheter when a continuous infusion is converted to an intermittent access. This method of intermittent access is sometimes called a saline lock. The NC is designed to accommodate the tip of a syringe or IV tubing for catheter flushing or intermittent administration of solutions into the vascular system.

Advantages to Intermittent Infusions

- Provide access to the vascular system without the patient being attached to a continuous infusion, allowing greater patient mobility

- Allow for reduced volume of fluid administered, important for patients at risk (e.g., those with heart failure)

- Provide access for delivery of emergency medications

Disadvantages

- May increase risk for BSI due to more manipulation at the catheter hub and thus opportunity for intraluminal entry of microbes; attention to disinfection and ANTT is essential with every catheter access

Needleless Connectors

Important issues related to NCs include frequency of device change and adherence to ANTT when accessing the NC for infusion, flushing, and locking. The NC is changed on a regular basis as follows: no more often than every 96 hours; or when the IV tubing is changed, residual blood is present in the device; and whenever the integrity is compromised or contamination is suspected (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S106).

Because NCs are a known source of contamination, attention to disinfection when accessing the NC for VAD flushing and medication administration is critical in reducing the intraluminal introduction of microbes. Guidance and options for disinfection are addressed in Chapter 2.

Maintaining Catheter Patency: Flushing and Locking

The terms flushing and locking are commonly used yet sometimes misunderstood. Catheters are flushed after each intermittent infusion to clear any medication from the catheter and to prevent contact between incompatible medications or IV solutions. When a catheter is not properly flushed, a precipitate may form or blood may reflux into the catheter, resulting in occlusion. Catheters are flushed with preservative-free 0.9% sodium chloride. Catheter flushing is performed with medications administered via a port on the administration set into a continuous infusion and with intermittent infusions (i.e., saline lock). Catheter locking is used with intermittently accessed peripheral catheters and refers to the solution left instilled in the catheter to prevent occlusion in between intermittent infusions.

- Flush PIVCs and midline catheters with 0.9% preservative-free sodium chloride before and after administration of medication and lock with 0.9% preservative-free sodium chloride at least every 24 hours if the catheter is not in use. Caution: If the PIVC or midline catheter is not being used at least once every 24 hours, consider removal if no longer being actively used for infusion! The INS recommends a minimum volume for flushing equal to twice the internal volume of the catheter plus any add-on device and a locking volume equal to the internal catheter volume plus 20% (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S114). The internal volumes of peripheral and midline catheters are fractions of 1 mL. Organizations typically will use the smallest available prefilled flush syringe (e.g., 2 to 3 mL) for both flushing and locking.

NURSING FAST FACT!

NURSING FAST FACT!Some medications are incompatible with 0.9% sodium chloride. In this case, 5% dextrose in water is used for flushing, followed by normal saline and/or a heparin solution. Dextrose should not be left in the catheter lumen because it provides nutrients for growth of bacteria (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S113). |

NURSING FAST FACT!

NURSING FAST FACT!Pulsatile versus a consistent smooth flushing technique: Based on in vitro studies, the INS suggests consideration for use of a pulsatile (e.g., push-pause-push-pause) flushing technique to better clear the catheter of solid deposits (e.g., fibrin, drug precipitate) (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S114). Theoretically, this recreates a turbulence within the catheter lumen that causes a swirling effect to move any debris (residues of fibrin or medication) attached to the catheter lumen. However, it also has been suggested that pulsatile flushing of PIVCs could cause damage to the tunica intima (Zhu et al., 2020). More clinical studies are needed to provide a better understanding of pulsatile flushing. |

NOTE: Refer to Procedures Display 6-2 at the end of this chapter for “Flushing and Locking a Short PIVC or Midline Catheter After an Intermittent Infusion.”

All VADs, including PIVCs and midline catheters, should be removed when there is evidence of a complication (e.g., signs of phlebitis or infiltration), when therapy is discontinued, and when the device is no longer necessary. Short PIVCs and midline catheters should be removed if the catheter is no longer included in the plan of care or it has not been used for 24 hours or more (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S133).

INS Standard PIVCs placed under suboptimal aseptic conditions in any health care setting (i.e., emergent) should be removed and a new catheter inserted as soon as possible, within 24 to 48 hours (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S133).

ADULT PIVC INSERTION

Nursing Assessment

Key Nursing Interventions 1. Verify provider order for infusion therapy. 2. Gather all supplies and prepare the infusate/infusion method as indicated. 3. Provide patient education preparing patient for procedure. 4. Choose an appropriate vein and appropriate-size PIVC. 5. Evaluate and implement appropriate interventions for pain management. 6. Maintain standard precautions and adhere to ANTT during insertion and PIVC maintenance. 7. Apply securement device and dressing after PIVC placement. 8. Initiate infusion. 9. Document the procedure and observations of the site. |

PIVCs and Pediatric Patients

Physical Assessment

A physical assessment of pediatric patients should be performed before IV therapy is initiated. Table 6-8 lists the components of a pediatric assessment. Risk factors that must be considered during the assessment phase include prematurity, catabolic disease state, hypothermia, hyperthermia, metabolic or respiratory alkalosis or acidosis, and other metabolic abnormalities.

| Measurement of head circumference (up to 1 year) Height or length Weight Vital signs Skin turgor Presence of tears Moistness and color of mucous membranes Intake and urinary output Characteristics of fontanelles Level of child's activity related to growth and development |

Site Selection

When selecting the venipuncture site, keep in mind that the main goal of infusion therapy is to provide the treatment with safety and efficiency while meeting the child's emotional and developmental needs.

Consider the following factors before selecting a site for venipuncture:

- Child's age and size

- Condition of veins

- Objective/type of infusion therapy (hydration, administration of medication, etc.)

- General patient condition

- Mobility and level of activity of child

- Gross and fine motor skills (e.g., sucks fingers, plays with hands, holds bottle, draws)

- Sense of body image

- Developmental level of the child (i.e., can understand and follow directions)

Peripheral Sites

For pediatric patients in general, the hand and forearm may be used for PIVC insertion. The antecubital fossa should not be used routinely for peripheral IV access, as it is an area of flexion with an increased risk for infiltration. It should be reserved for blood drawing and may be used in emergency situations for vascular access.

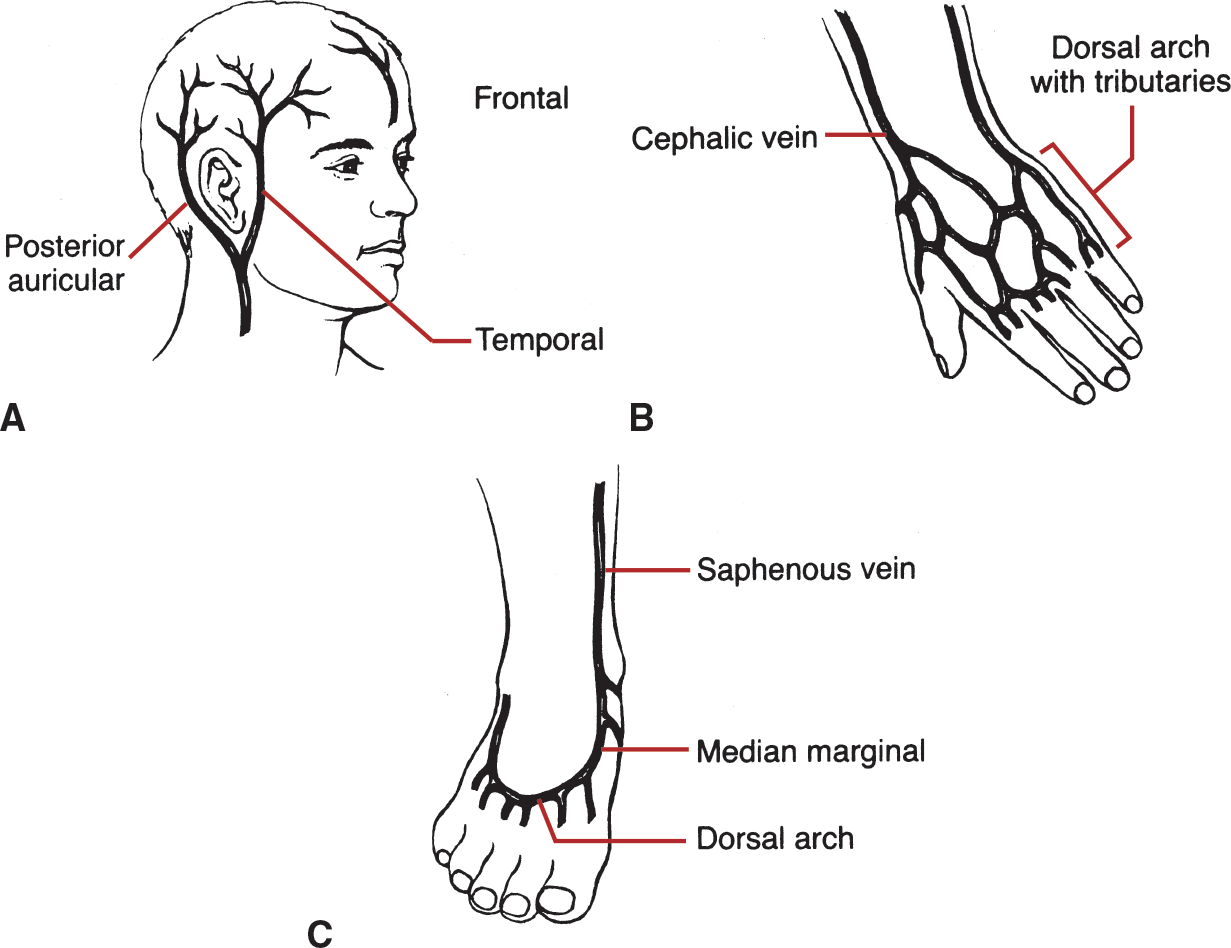

For neonates and infants, recommended PIVC sites include the forearm and the foot. Notably, use of the lower extremity is appropriate only until the child is not walking, and sites to avoid include the hands, fingers, and thumbs. Advantages and disadvantages of these sites are found in Table 6-9. Aside from the upper arm, midline catheters may be inserted in leg veins (e.g., saphenous, popliteal, femoral) with the catheter tip located below the inguinal crease (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S82).

| Veins and Site | Age Appropriate | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scalp | |||

| Superficial temporal (front of ear) Frontal (middle of forehead) Occipital Posterior auricular | Infant younger than 18 months of age | Highly visible Easily accessed and monitored Veins readily dilate Keeps feet and hands free No valves | Hair must be trimmed Infiltrates easily Difficult to stabilize device Increased familial anxiety May have cultural issues |

| Lower Extremities | |||

| Leg: Saphenous Foot: Metatarsal | Infant: Used before crawling and walking | Large vessels Readily dilate Hands kept free Easily restrained/splinted | Decreased mobility Located near arterial structures Difficult to observe/palpate in chubby infants Risk of phlebitis is increased |

| Hand | |||

| Metacarpal | All ages | Easily accessible/visible in older children Distal location May not require splinting | Uncomfortable Difficult to anchor/stabilize May impede child's activities (thumb-sucking, schoolwork) Difficult to observe/palpate in chubby infants/toddlers |

| Forearm | |||

| Cephalic Basilic Median antebrachial | All ages | Same as for hand Keeps hands free | Difficult to observe/palpate in chubby toddlers |

Scalp Veins

Scalp veins are used in neonates and infants only as a last resort and must be inserted by a competent clinician (Cho et al., 2021; Gorski et al., 2021, p. S82). The scalp veins are prominent and valveless. The three most commonly used scalp veins are the superficial temporal, frontal, and posterior auricular (Fig. 6-18). Venous distention is accomplished by gentle pressure at the site or use of an elastic constricting band placed below the site but above the eyes and ears; ultrasound guidance may be used (Cho et al., 2021). The choice of a scalp vein for placement of IV therapy may be traumatic for the parents because removal of hair sometimes has cultural and religious significance.

The IV catheter must be placed in the direction of blood flow to ensure that the IV fluid will flow in the same direction as the blood returning to the heart. In the scalp, venous blood generally flows from the top of the head down.

NOTE: Never shave hair; if hair removal is necessary, clip the hair.

NURSING FAST FACT!

NURSING FAST FACT!The foot should be secured on a padded board with a normal joint position. |

Catheter Gauge

The smallest gauge PIVC needed to accommodate the prescribed infusion therapy is used (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S75). A 22- to 26-gauge catheter is recommended for neonates and pediatric patients.

Venipuncture Tips

1.Have extra help whenever possible.

2.Infants should be covered with a blanket to minimize cold stress.

3.A flashlight or transilluminator device helps to illuminate tissue surrounding the vein; the veins are then outlined for better visualization. Only cold light sources should be used due to the risk of thermal burns (Gorski et al., 2021, p.S63).

4.Warm hands by washing them in warm water before gloving.

5.Minimizing pain during venipuncture is a goal of nursing care. Use anesthetics and behavioral interventions as addressed in Step 6.

NOTE: Use colored stickers or drawings on the IV site as a reward.

NURSING FAST FACT!

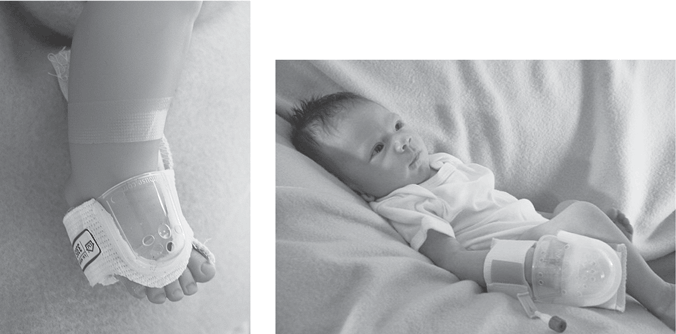

NURSING FAST FACT!Securing and maintaining the patency of a PIVC can be a challenge. Poorly secured IV access sites may result in dislodgements or infiltrations requiring IV restarts. Products are available to protect the pediatric IV while maintaining visualization, such as a clear, one-piece unit (Fig. 6-19). The use of infiltration technology is a consideration; in one study results included 80% sensitivity in detecting infiltrations and initiating a notification before the nurse identified infiltration through assessment (Doellman & Rineair, 2019). |

Children's understanding of, reaction to, and methods of coping with illness or hospitalization are influenced by the significance of individual stressors during each developmental phase. Major stressors include separation, loss of control, and bodily injury.

Site Care and Maintenance

Inspect and monitor the VAD, connections, infusate prescribed, and pump functions, including flow rate. Perform site checks minimally every hour (Gorski et al., 2021). Assess the range of motion of the cannulated extremity, taking into consideration the child's developmental age. Monitor the patient's overall response to therapy. Remove and replace short PIVCs based on clinical condition of the site.

PEDIATRIC PIVC INSERTION

Nursing Assessment

Key Nursing Interventions 1. Explain the procedure and equipment and the rationale for treatment to the parents and child, if appropriate. Verify assent (agreement) to the procedure for school-aged children (7 years) using language and learning methods appropriate to the child's age (Gorski et al., 2021, p. S39). 2. Address pain management for PIVC insertion: For infants, provide opportunities for non-nutritive sucking (i.e., sucrose); for older children, consider both pharmacological and nonpharmacological management, including cognitive and behavioral strategies such as distraction. 3. Encourage parents to provide daily care of the child. 4. Maintain the daily routine during hospitalization. 5. Provide a quiet, uninterrupted environment during naptime and nighttime as appropriate. 6. Use appropriate equipment for delivery of safe infusions (e.g., volume chamber, electronic infusion pump, syringe pump) (Chapters 5, 10). 7. Use an independent double check of dosage calculations with another health-care provider (e.g., nurse, pharmacist) before administration. |

Peripheral Infusion Therapy in the Older Adult

As with the pediatric patient, care of the older adult has become an area of specialty nursing that requires special approaches to infusion-related care. Consider the following statistics (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2020):

- In the United States, there were 52 million persons 65 years or older in 2018 (the latest year for which data are available), representing 16% of the U.S. population (about one in every seven Americans).

- The older population in 2030 is projected to be more than twice as large as in 2000, growing from 35 million to 73 million and representing 21 percent of the total U.S. population

Physiological Changes

The skin is one of the first systems to show signs of the aging process. The epidermis and dermis are visible markers of aging and impact the placement of peripheral catheters. The most striking change is an approximately 20% loss in thickness of the dermal layer, which results in the paper-thin appearance of aging skin (Baranoski et al., 2020). This results also in decreased pain perception, which potentially makes older patients less likely to feel and report pain with infiltration or phlebitis. Purpura and ecchymoses may appear as a result of the greater fragility of the dermal and subcutaneous vessels and the loss of support for the skin capillaries. Minor trauma can easily cause bruising.

A common symptom in older people is pruritus or “itchiness.” Dryer skin may result from atrophy of sweat glands in the dermal layer as well as from medications and should be considered when preparing the patient for parenteral therapy.

NURSING FAST FACT!

NURSING FAST FACT!Alcohol, when used in skin antisepsis, will add to the drying effect on the skin. |

The dermis becomes relatively dehydrated and loses strength and elasticity. This layer has underlying papillae that hold the epidermis and dermis together; thus, as a person ages, the older skin loosens. Older skin has decreased flexibility of collagen fibers, increased fragility of the capillaries, and fewer capillaries (Fig. 6-20).

Websites

Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing: https://consultgeri.org/

American Geriatrics Society: www.americangeriatrics.org

Venipuncture Techniques

Special venipuncture techniques are required to successfully place and maintain infusion therapy in older patients. The tunica intima and the tunica media become thicker, making vein entry more difficult, and the valves also become more rigid and sclerotic (Coulter, 2016). Veins are more fragile and may be more likely to rupture. The potential complications associated with trauma, surgery, and illness in the older adult, along with the physiological changes previously addressed, require that nurses understand aging and implications for nursing practice. Because the older adult patient may be at greater risk for potential complications related to infusion therapy, frequent monitoring is required. For example, even small infiltrations can lead to significant complications.

Vein Selection

The forearm is the recommended site. Areas for PIVC access should have adequate tissue and skeletal support. Avoid areas of flexion and areas with bruising. A low angle is best to avoid nicking or going through the underside of the vein wall (Coulter, 2016). Do not stab or thrust the catheter into the skin, which could cause the catheter to advance too deeply and accidentally damage the vein. Use the indirect method (two-step) for patients with small, delicate veins.

Apply a tourniquet lightly to help distend and locate appropriate veins and in some cases, a tourniquet may not be needed. During venous distention, palpate the vein to determine its condition. Veins that feel ribbed or rippled may distend readily when a tourniquet is applied, but these sites are often difficult to access. Table 6-10 summarizes tips for use with fragile veins.

NURSING FAST FACT!

NURSING FAST FACT!Place a tourniquet over a gown or sleeve to decrease the shearing force on fragile skin. |

Valves become stiff and less effective with age. Bumps along the vein path (i.e., valves) may cause problems during attempts at vein access. Venous circulation may be sluggish, resulting in slow venous return, distention, venous stasis, and dependent edema.

OLDER ADULT PERIPHERAL INFUSION

Nursing Assessment

Key Nursing Interventions 1. Use small-gauge catheters (22 to 24 gauge). 2. Avoid tight tourniquet use; avoid use or consider use of blood pressure cuff 3. Stabilize vein and insert the PIVC at a low angle (5 to 15 degrees) 4. Explain procedures, be alert to possible sensory or auditory deficits. |

The following tips are for patients with fragile veins (age or disease process related):

|

Home Care Issues

Home Care IssuesA PIVC is generally indicated for short-term (e.g., 7 days) or infrequent intermittent infusions (e.g., monthly infusion) of nonirritating drugs and fluids. The use of midline catheters is common in home care, especially for 1- to 2-week courses of IV antibiotic therapy. Home-care issues related to the initiation and maintenance of PIVC administration include technical procedures, such as infusion administration and site rotation, as well as monitoring for expected effects and potential adverse reactions. The degree to which the patient is expected to learn and perform technical procedures depends on his or her cognitive ability, willingness to learn, and the specific technique being taught. In some cases, the patient/caregiver may administer the infusions; in other cases, the nurse administers each dose. For a patient/caregiver who administers PIVC infusions, teaching will address administration sets, setting up and monitoring infusion pumps, and adhering to aseptic technique with all procedures. Challenges in the home setting include:

The home-care environment must be assessed to be sure that infusion therapy can be carried out safely. In the home, children are more mobile and active. The parents must be educated about the use and care of therapy and accept involvement in and responsibility for the treatment regimen. Depending on the age, the child may want to participate in infusion therapy.

Educating older adults on the administration of home infusion therapy can present challenges. Sensory changes (e.g., vision, hearing, manual dexterity) occur as part of the normal aging process and may have an impact on the teaching-learning process. Suggestions include:

|

NURSING FAST FACT!

NURSING FAST FACT!The home-care nursing staff is responsible for routine restarts of PIVC or blood draws. (In some areas, home laboratory services are also available for routine phlebotomy for needed laboratory studies.) |

Age-Related Considerations

Age-Related Considerations