This is the concluding chapter in this text, but in another sense, it is the beginning of your professional journey. Leadership is key to the success of the profession, so we end with a discussion about leadership and connect content found in this text. Content related to leadership is found throughout this text, such as in discussions about the development of the profession, nursing education, healthcare policy, legal and ethical issues, standards, healthcare organizations (HCOs), coordination and collaboration, communication, interprofessional teams, delegation, conflict resolution, evidence-based practice (EBP) and research, and the healthcare professions and nursing competencies. This discussion does not end with this text or in a course that introduces the critical elements of the nursing profession. Instead, this chapter marks a beginning because it highlights key concerns introduced elsewhere in the text, and the content focuses on the future of nursing and the need for greater leadership-both for the profession and for individual nurses. This content also explores some of the emerging issues, trends, and initiatives important to the nursing profession and the need for greater nursing leadership. More changes are predicted for the future, but most are unknown. You are the future of nursing, and all this content is relevant to you.

Leadership and Management in Nursing

Leadership is important for every nurse, whether the nurse is in a formal administrative/management position or not, during routine practice and times of change and stress. For example, we saw the need for strong nursing leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic to guide staff in practice and in nursing education, particularly in adapting over time to meet practice needs and student requirements. All settings and practice areas require that nursing leaders demonstrate leadership characteristics and competencies and ensure that the nursing profession is an active participant in the healthcare delivery system and in the development and implementation of healthcare policy. The Future of Nursing reports support this perspective by emphasizing the need for nurses to assume more leadership in health care, and to accomplish this, nurses need greater leadership competency, as noted in revisions of nursing education standards (NAM, 2021; AACN, 2021; IOM, 2011).

Leadership Models and Theories

A good place to begin to better understand nursing leadership is with an overview of leadership models and theories, critical issues, and a comparison of leadership and management. Leadership and management are not the same, although effective managers need to demonstrate leadership. In general, earlier leadership models and theories emphasized control and getting the job done with little, if any, emphasis on creativity and innovation or staff participation in decision-making. The following is a summary of some of the key models and theories to illustrate how they have changed over time.

- Autocratic: The formal leader (manager/administrator) makes decisions for the staff; the model assumes staff members are not able and/or not interested in participating in decision-making.

- Bureaucratic: The focus is on structure, rules, and policies, with decision-making placed in the hands of the formal leader (manager/administrator). Staff members receive directions from managers. This approach is related to the autocratic approach.

- Laissez-faire: The formal leader (manager/administrator) turns over decision-making to the staff, steps back from participation, and lets things happen with little, if any, direction. This can lead to problems because it often means the organization or process may be leaderless; it is a difficult balance to provide some leadership but to do so in the background.

These models and theories have long been used in health care. Some HCOs still use them or some adaptation of them. Nevertheless, these approaches are not effective in today's rapidly changing environment, where staff members want to participate more and seek recognition for their performance and expertise. However, they still expect leaders to guide the overall process. Over time, new models and theories that built on one another developed. Often, these changes began in other industries and then were adopted by HCOs. Some of these newer theories are highlighted here:

- Deming's theory: Effective organizations are dependent on group or team interaction.

- Drucker's theory: This theory, which is referred to as modern management, builds on Deming's recognition of the importance of staff team participation in the organization and yet also maintains the importance of individual autonomy.

- Contingency theory: Multiple variables affect situations, which in turn affect leader-member relationships, tasks, and position power.

- Connective leadership theory: The focus is on caring and connecting to others-individuals, groups, and organizations.

- Emotional intelligence theory: The focus is on leader-follower relationships, feelings, and self-awareness.

- Chaos or quantum theory: This is a more current theory that emphasizes interdependency, sensitivity to change, avoidance of predicting too far into the future, and accountability in the hands of those who do the work (Albert et al., 2021).

- Knowledge management theory: This theory turns attention to knowledge-the knowledge worker, knowledge-intense organizations, interprofessional collaboration, and accountability. It recognizes the importance of technology and information today. Although this is a newer theory, it, too, has historical roots. For example, Drucker's theory used the term “knowledge worker” to describe a person who works with his or her hands and with theoretical knowledge. Knowledge workers are assets for HCOs-for example, nurses should focus on knowledge and application of knowledge rather than being overly concerned with staff titles and positions.

As changes were made in leadership models and theories in the last 20 years, there has been a movement toward greater staff participation, recognition of staff performance, staff and staff-manager relationships, teamwork, and collaboration. This is very different from autocratic, bureaucratic, or even laissez-faire leadership approaches.

As a result of these changes, a newer leadership theory stands out today-a theory that has connections to the theories previously described. In early Quality Chasm reports, experts recommended that the best leadership style today for healthcare delivery is transformational leadership. This approach emphasizes a positive work environment, recognition of the importance of change and using change effectively, rewarding staff for expertise and performance, and development of staff awareness of work processes so that they can engage in quality improvement (IOM, 2003a). Transformational leaders create vision and mission statements with staff to guide the work of the organization. They view change as an opportunity and are described as honest, energetic, loyal, confident, self-directed, flexible, and committed. Staff members can see these characteristics in a transformational leader and want to work for and with this leader. Some studies indicate that there is a connection between staff perceiving their nursing leaders as transformational leaders and staff perceptions of a positive work environment; there is less staff burnout and more staff engagement in this work environment and its processes (Lewis & Cunningham, 2016). This type of study further supports the need for transformational leadership and more nursing research to better understand this type of leadership.

Nursing Professional Governance: Empowering Nursing Staff

With the changing healthcare environment and changes in leadership and management models or theories, there is a greater need to focus more on team efforts as has been noted throughout this text. These changes led to the development and greater use of nursing professional governance (NPG) (shared decision-making), which “can be viewed as a management philosophy, a professional practice model, and an accountability model that focuses on staff involvement in decision-making, particularly in decisions that affect their practice” (Finkelman, 2024, p. 115). Through NPG, nurses in an organization can (Hess, 2004):

- Control their professional practice.

- Influence organizational resources that support practice.

- Gain formal authority, which is granted by the organization.

- Participate in decision-making through committee structure.

- Access information about the organization.

- Set goals and negotiate conflict.

The term “shared governance” has been replaced with “nursing professional governance” (Raso, 2019; Porter-O'Grady & Clavelle, 2021; O'Grady, 2017). As was true for shared governance, this is an approach that focuses on engaging staff at all levels in decision-making, and the same characteristics noted above apply. Nurse managers are not the only decision-makers in this practice model, and there is now greater emphasis on self-management and control over practice, which should develop nurses who are more efficient, accountable, and feel empowered. When HCOs establish NPG, they may begin by using the “Structural Professional Governance Self-Assessment Survey (SPGS - A) which addresses structural requisites needed to support and advance the behavioral attributes of professional governance: accountability, professional obligation, collateral relationships, and effective decision making” (Porter-O'Grady & Clavelle, 2021, p. 195). Information gathered from this survey then guides the development and implementation of the organization's NPG.

When NPG is used, as was also true for shared governance, nurses assume an active role in the management of patient care services and thus have more control over their practice (Murray et al., 2016). This is a management model that emphasizes the need for nurses to share accountability and responsibility and typically leads to increased staff commitment to the HCO. Nurses have the authority to make sure the right decisions are made about the work they do. Accountability means that the nurse accepts responsibility for outcomes or is answerable for what is done. Responsibility means to be “entrusted with a particular function” (Ritter-Teitel, 2002, p. 34). These aspects of management are connected to autonomy, or the right to make decisions and control actions. The most effective approach occurs when the nurse who provides care is also the staff member who works to resolve issues and ensure that patient outcomes are achieved at the point of care, limiting the number or layers of staff who must be involved in improving care. This is more effective than someone far above the direct-care situation telling staff what they must do to improve. It is important to recognize that NPG is dependent on effective collaboration, communication, and teamwork and spreads departmental and organizational decision-making over many staff, providing opportunities for more decentralized decision-making. This approach, however, does not mean that managers can ignore their managerial and leadership responsibilities or that all decisions are made by the staff. If the process blocks decision-making-for example, by taking too long to make a decision-then this model will not be effective. This approach means that with staff inclusion managers must do their jobs differently. NPG is not easy to develop, and sometimes, it can become a barrier to the delivery of efficient, high-quality care, but it is usually helpful. It takes time to develop an effective NPG structure and culture and then maintain it, which is something that both management and staff need to recognize.

HCOs may vary in how they structure NPG, but the principles are typically the same-as described here. For example, a hospital may have a nursing council with different nursing staff represented, and the council makes certain decisions about the operation of nursing services with committees and task forces working on various aspects to ensure effective nursing care and meeting staff work needs, such as staffing, scheduling, education, salaries and benefits, promotion structure, and so on. Typically, hospitals that use an NPG model have more satisfied staff members and lower staff turnover. Staff like working in this type of organization and describe it as a positive work environment. Not all hospitals use NPG, and its implementation and effectiveness can vary widely, but many are applying it and finding it improves the organization, performance, management, and patient outcomes.

Leadership Versus Management

It is easy to confuse leadership and management. A leader can be a leader and not a manager, just as a manager can be a manager and not a leader. A leader provides overall guidance and supports staff engagement at all levels of the organization. A manager holds a formal management or administrative position and, in that position, focuses on four major management functions: planning, organizing, leading, and controlling. Today, effective nurse managers need to be able to collaborate, communicate, coordinate, delegate, recognize the importance of data and outcomes; manage resources (budget, staff, equipment, supplies, space, and so on); improve staff performance and patient outcomes; develop and support teams; and evaluate effectiveness and efficiency. In management positions, nurses must actively support and apply evidence-based practice (EBP), evidence-based management (EBM), and QI. Nurse managers need to use critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and judgment, and be flexible and adjust to change using the planning process. The nurse manager role has changed over time, particularly due to the changing healthcare environment and changes in leadership and management models, and there is greater emphasis on QI as a critical requirement for managers.

When someone is described as a leader, this is often due to the person's ability to influence others; however, this does not necessarily mean that the person viewed as a leader is in a formal management position. In contrast, managers have power because they hold formal management positions, such as team leader, nurse manager, department director or supervisor, or chief nursing officer. Ideally, all managers should also be leaders and viewed as leaders by their staff, but this does not always happen. Bennis and Goldsmith described one viewpoint on the difference between leaders and managers, which continues to be important to recognize (1997, p. 4): “There is a profound difference-a chasm-between leaders and managers. A good manager does things right. A leader does the right thing.” This view continues to be important. A problem in HCOs and in nursing is the existence of the Peter Principle, which occurs when someone is promoted beyond the leadership and management competencies required for a new position. This is a particular problem in nursing as it is not uncommon to promote a very competent clinical nurse to a management position and assume that this will lead to management success. In many cases, it does not.

Major changes in healthcare delivery have led to the need for changes in leadership and management. The following aspects of leadership continue to be important and impact management (Porter-O'Grady, 1999, p. 40):

- Change focus from process to outcomes.

- Align role to the information infrastructure rather than to functional performance.

- Focus on team results rather than individual performance.

- Manage data complexes rather than individual events.

- Facilitate resources that then direct work.

- Transfer skill sets rather than make decisions for staff.

- Develop staff self-direction rather than giving direction.

- Focus on obtaining value rather than simply finding costs.

- Focus on consumer-driven structure rather than provider-based system.

- Construct horizontal relationships rather than maintain vertical control mechanisms.

- Facilitate equity-based partnerships rather than control individual behaviors.

Consideration of these factors provides greater opportunity to develop and implement transformational leadership, and an effective nurse manager should demonstrate transformational leadership.

There are many myths about leadership that are important to address, and three of them are key for nursing leaders to consider as they develop their own leadership or develop other nurses for leadership (Goffee & Jones, 2000).

- Everyone can be a leader. This is not true. While everyone may have the potential to be a leader, it is important to recognize that leadership competencies can and must be developed for a person to be a leader.

- People who get to the top are leaders. This is not true. Many people in high-level administrative positions may not be described as leaders; in some cases, their staff may not even describe them as effective managers.

- Leaders deliver business results. This is not true. Leaders do not always meet expected outcomes; sometimes, they are not effective managers.

HCOs need to support the development of nursing staff leadership, and nurses need to develop their own leadership. Leaders do not just happen; they need education, guidance and support, mentoring, and ongoing development.

Nursing Management Positions

Nurse managers today have much more responsibility than in the past. The main purpose of management is to get the job done effectively. There are three common levels of management. The first level includes managers who work with staff daily to complete required work. The typical title at this level is nurse manager, though HCO titles may vary. This person guides and supervises a unit's nursing staff, both professional and nonprofessional, to ensure that quality patient care is delivered at the clinical unit level. The second level in an organization consists of middle managers who supervise multiple first-level managers. Such managers might include a nursing supervisor or director who supervises all the unit nurse managers, for example, in a medical division or all the nurse managers in the ambulatory care clinics and the emergency department. Middle-level managers report to upper-level managers, such as the chief nursing officer or director. The upper level is the chief nursing officer (CNO) or nurse executive. This nurse manager is responsible for the overall work of the nursing service/department and, in some cases, may be responsible for services in addition to nursing and is considered a member of the HCO administration. Regardless of level, the manager must be able to perform management functions and demonstrate leadership.

This description is the most common structure for nursing management in HCOs, such as hospitals; however, there are variations from organization to organization. In addition, some staff may hold nonmanagerial positions, but they also need to be effective leaders and demonstrate some management functions, such as planning. These individuals do not have supervisory responsibilities because they do not always direct and evaluate staff, but they must influence staff. For example, a clinical nurse specialist (CNS), advanced practice registered nurse (APRN), clinical nurse leader (CNL), or nurse informaticist may hold this type of position.

| Stop and Consider 1 |

|---|

| Leadership and management are part of nursing professional governance. |

Factors That Influence Leadership

Many factors influence the development of leadership competencies and the practice of effective leadership. Some of the factors are organization based, such as administrative support of effective leadership development, clear communication and processes, recognition and empowerment, application of evidence-based management (EBM), and so on. Other factors are focused more on individuals who are leaders or aspire to improve and be leaders. Examples of factors are education (academic, staff education, continuing professional education), self-esteem, ability to communicate, ability to ask for guidance, effective use of problem-solving, ability to develop and communicate a vision, ability to engage others in the work process, and so on. The following sections include a discussion of some factors that should be considered in developing leadership at organizational and individual staff levels.

Generational Issues in Nursing: Impact on Image

Generational issues are important in describing the nursing profession and its image and have an impact on the nursing practice and management and, consequently, on leadership and teamwork (Moore et al., 2016). When a person thinks of a nurse, which generation or age groups are considered? Most people probably do not realize that there is not one age group but rather several represented in nursing. Today, nursing staff includes representation from multiple generations: baby boomers (born 1946-1964), Gen X/latch key (born 1965-1976), Gen Y/millennials (born 1977-1991), Gen Z/iGeneration (born 1992-present). The so-called “traditional generation” is no longer in practice, but this generation had a significant impact on the nursing profession and current practice (DiBlasi-Moorehead & Calawerts, 2020).

Nurses in these generations are different from one another. How does this affect the image of nursing? It means that nursing includes multiple age groups with different historical backgrounds and viewpoints. How nurses from each generation view nursing can be quite different. Their educational backgrounds vary a great deal, from nurses who entered nursing through diploma programs to nurses who entered through baccalaureate programs, and then may have completed graduate degrees. Some of these nurses have seen great changes in health care, and others see the current status as the way it has always been. Technology, for example, is frequently taken for granted by some nurses who have always been involved in technology, whereas others are overwhelmed with technological advances, which is something they did not have earlier in their personal lives. Some nurses have seen great changes in the roles of nurses, whereas other nurses now take the roles for granted-for example, the APRN role. If one asked a nurse in each generation for the nurse's view of nursing, the answers might be quite different in how nurses practice, settings in which nurses practice, management responsibilities, and so on. If these nurses then tried to explain their views to the public, the perception of nursing would most likely consist of multiple images.

The situation of multiple generations in one profession provides opportunities to enhance the profession through the diversity in their ages and their experiences, but it has also caused problems in the workplace when they may have different views of work and the profession. What are the characteristics of the various groups? How well do they mesh with the healthcare environment? How well do they work together? The following list summarizes some of the characteristics of each generation, including the traditional generation and its impact (Finkelman, 2024; DiBlasi-Moorehead & Calawerts, 2020; Moore et al., 2016):

- Traditional (silent or mature) generation: This generation is important because of its historical impact on nursing, but members of this group are no longer in practice. This group was hardworking, loyal, and family focused, and they felt that duty to work was important. Many served in the military in World War II and the Korean War. This period occurred prior to the women's liberation movement. The characteristics of the traditional generation had a major impact on how nursing services were organized and nurses' expectations of management. Some of this impact has been negative, such as the emphasis on bureaucratic structure, and it has been difficult to change this in some HCOs.

- Baby boomers: This generation, which is currently the largest in the workforce, is the group moving into the retirement process or recently retired. This trend is predicted to lead to greater nursing shortage problems in the future. The baby boomer generation grew up in a time of major changes, including the women's liberation movement, the civil rights movement, and the Vietnam War. They had fewer professional opportunities than are available to nurses today because the typical career choices for women were either teaching or nursing. This began to change as the women's liberation movement grew, for example, opening other opportunities in medicine, law, business, and so on. Within this generation, fewer men went into nursing, as was true of the previous generation. This group's characteristics include independence, acceptance of authority, loyalty to the employer, workaholic tendencies, and less experience with technology, although many in this group led the drive for adoption of more technology in nursing. This generation is often more materialistic and competitive and appreciates consensus leadership. It is a generation whose members chose a career and then stuck to it, even if they were not very happy with that choice.

- Generation X (Latch Key): The presence of Generation X, along with Generation Y, is increasing in nursing. Members of this group are assuming more nursing leadership roles as the baby boomers retire. Gen Xers are more accomplished in technology and very involved with computers and other advances in communication and information (social media), both in their personal lives and in healthcare delivery. In their lifetimes, they have experienced many changes in these areas. These nurses want to be led, not managed, and they may not have developed high levels of self-confidence and empowerment. What do they want in leaders? They look for leaders who are motivational, demonstrate positive communication, appreciate team players, and exhibit good people skills-leaders who are approachable and supportive. Baby boomers, in contrast, would not look for these characteristics in a leader. Gen Xers typically do not join organizations (which has implications for nursing organizations that need more members and active members), do not feel they must stay in the same job for a long time (which has implications for employers that experience staff turnover and related costs), and want a good balance between work and personal life (which means that they are less willing to bring work home). Compared with earlier generations of nurses, members of Generation X are more informal, pragmatic, technoliterate, independent, creative, intimidated by authority, and loyal to those they know; they also appreciate diversity. By contrast, the baby boomers with whom the Gen Xers work often see things very differently. Baby boomers are more loyal to their employer, stay in the job longer, are more willing to work overtime (although they are not happy about it), and have greater long-term commitment. These differences may cause problems between generations, with baby boomers often occupying supervisory positions or senior faculty positions and Gen Xers found in staff positions or beginning faculty positions but moving into more leadership positions. It is a critical time of leadership transition in the profession.

- Generation Y (millennials): The millennial generation is the newest generation in nursing, although second-career students and older students are also entering the profession who might be older and thus may represent an earlier generation. Key characteristics of this generation are optimism, civic duty, confidence, achievement, social ability, morality, and diversity. In work situations, they demonstrate collective action, optimism, tenacity, multitasking, and a high level of technology skill, and they are also more trusting of centralized authority than Generation X. Typically, they handle change better, take risks, and want to be challenged. This generation is connected to mobile phones and personal electronic devices and uses various social networking methods. They are tech-savvy and expect to multitask. Sometimes, however, this makes it difficult for them to focus on one task.

- Generation Z (iGeneration): This generation of nurses is just now entering the profession, so their impact and how they will adjust is still in process. They are highly digital, born at the time of the development of the public use of the internet. “These digital natives spend most of their day consuming and using technology. As a result, they're individualistic and can have underdeveloped social and relationship skills that may lead to anxiety, insecurity, and depression. Their use of the internet may lead to a short attention span and a desire for immediacy and convenience” (Chicca & Shellenbarker, 2019, p. 48). This generation of nurses is more diverse and more likely to be active in social issues. Personally, they are concerned about emotional, physical, and financial security, which impacts their view of employment, relationships with employer and supervisor, and the need for clear communication, feedback, and engagement. Given their experience with technology and level of use in daily job activities, these nurses may need help developing and maintaining interpersonal competencies related to staff-staff, staff-manager, and staff-patient experiences. Considering all of this has an impact on staff retention, teamwork, and staff satisfaction.

In a profession that includes representatives from multiple generations, it is necessary to recognize that age diversity means variations in positive and negative characteristics among staff. Some will pull the profession backward if allowed, and some will push the profession forward. “In the workplace, differing work ethics, communication preferences, manners, and attitudes toward authority are key areas of conflict” (Siela, 2006, p. 47). This also has an impact on the nursing profession's image. As discussed here, nursing is not a profession that encompasses just one type of person or one age group, and people in different age groups are now entering nursing. We are long past the time when mostly 18-year-olds enter nursing education programs. As one generation moves toward retirement, the next generation will undoubtedly have a greater impact on the image of nursing. It is critical to avoid gender role stereotyping, and there is need to increase the strength of nurses as one group of professionals, while still recognizing that these differences exist and appreciating how they might affect the profession.

Power and Empowerment

Power and empowerment are connected to the image of nursing and the ability to assume leadership. How one is viewed can affect whether the person is considered to have power-the ability to influence, say what the profession is or is not, and influence decision-making. It is important to view power from both positive and negative perspectives. We know it can act as a barrier to success as a healthcare profession and affects teamwork, as discussed in other chapters, but how do power, powerlessness, and empowerment relate to nursing? They are critical elements influencing leadership and practice.

To feel as if no one is listening to you or you are not viewed positively can make a person feel powerless; this remains a long-standing problem for nurses. Many nurses believe that they cannot make an impact in clinical settings; management does not listen to them or seek their opinions. This powerlessness can result in nurses feeling like victims. The result may be resentment that is expressed as incivility, as discussed in other chapters in this text. The feeling of powerlessness can act against nurses when they do not actively address issues such as a negative image of nurses and when they allow others to describe what a nurse is or make decisions for nurses. This failure to be proactive merely worsens their image and diminishes professional self-esteem; both reduce leadership.

What nurses want and need is power-to be able to influence decisions and have an impact on issues that matter. Power can be used constructively or destructively, but the concern here with the nursing profession is using power constructively. Power and influence are related. Power is about gaining control to reach a goal. There is more than one type of power: informational, referent, expert, coercive, reward, and persuasive. The type of power a person possesses has an impact on how power can be used to reach goals or outcomes.

Empowerment is also an important issue for nurses today and is connected to leadership. Leaders who empower staff enable staff to act-a critical need in the nursing profession. Nursing professional governance emphasizes empowerment. Basically, empowerment is more than just saying you can participate in decision-making; staff need more than words. Empowerment is needed in day-to-day practice as nurses meet the needs of patients in hospitals, the community, and home settings. Empowerment also implies that some individuals may lose their power while others gain power. This can lead to conflict, which needs to be resolved so that it does not negatively affect the work environment and patient care.

Staff members who experience empowerment feel that they are respected and trusted to be active participants. This also helps them demonstrate a positive image to other healthcare team members, patients and their families, and the public. Nurses who do not feel empowered will not be effective in conveying a positive image because they will not be able to communicate that nurses are professionals with much to offer. Empowerment that is not clear to staff or not supported by management is just as problematic as a lack of staff empowerment. Empowered teams feel a responsibility for the team's performance and activities, which in turn can improve care and reduce errors.

Control over the nursing profession is a critical issue that is also related to the profession's image. Who should control the nursing profession, and who does? This is related to independence and autonomy-key characteristics of any profession. But an important question persists: What should be the image of nursing? As a profession, nursing does not appear to have a consensus about its image. This topic is discussed in other chapters, and here it is mentioned again as one considers nursing leadership and what nurses need to do to become more effective leaders in a complex healthcare delivery system. Nursing needs to control the image and visibility of the profession, and in doing so, if nurses have a more realistic image of themselves, they may exert more control over the solutions for the following four issues:

- Support the types of services that nurses offer to the public.

- Support an entry-level baccalaureate degree to provide the type of education needed to practice in the current healthcare environment.

- Support the need for reimbursement for nursing services, which involves much more than patient handholding, though this is also important.

- Participate as professionals in the interprofessional healthcare dialogue on the local, state, national, and international levels to influence policy.

Assertiveness

Earlier content in this text discussed assertiveness from the point of view of teams, but here we focus on nursing assertiveness and leadership. Assertiveness is demonstrated in a person's communication, which should be direct and open with appropriate respect for others. When a person communicates in an assertive manner, verbal and nonverbal communications are congruent, making the message clearer. Assertive persons are better able to confront problems in a constructive manner and do not remain silent. Problems with the nursing profession's image have been influenced by nursing's silence caused by the inability to be assertive, but assertiveness is a critical leadership competency. Katz identified other examples of assertive behavior (2009, p. 267):

- Express feelings without being nasty or overbearing.

- Acknowledge emotions but remain open to discussion.

- Express oneself and give others the chance to express themselves equally.

- Use I statements to defuse arguments.

- Ask for and give reasons.

This information provides a guide to improve and maintain effective assertiveness.

Advocacy in Leadership

Advocacy is speaking on behalf of something important, and it is one of the major nursing roles. Other content discussed advocacy for patients, but now we turn to advocacy as applied to the nursing profession and the need for nursing leaders to advocate for staff. All nurses represent nursing-acting as advocates in their daily work and in their personal lives (ANA, 2023a). When someone asks a nurse, “What kind of work do you do?” the nurse's response is a form of advocacy for the profession. The goal is to provide a positive, informative, and accurate response.

| Stop and Consider 2 |

|---|

| Power and empowerment should be part of the image of nursing. |

Scope of Practice: A Profession of Multiple Settings, Positions, and Specialties

Healthcare delivery requires nurses with multiple competencies and specialties to fulfill different roles in a variety of healthcare settings. Healthcare delivery is never static. For example, there is greater interest today in public/community health and, thus, an increased need for nurses to enter this healthcare area and hold a variety of positions. The following discussion considers some of the issues related to the variety of healthcare delivery settings and roles, some of which have been introduced in other chapters, but here the focus is on nursing leadership implications.

Along with understanding the nursing profession and workforce issues, certain U.S. demographics are important. In 2030, the baby boomer generation will be over 65, and it is projected that older people will outnumber children for the first time in U.S. history (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022). We do not yet know the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to the deaths of many older adults. There, however, will be changes in this patient population-leading to more patients with serious and chronic illnesses. A recent report addressed the need to prepare the healthcare workforce for these changes and provides examples of recommended strategies (NAM, 2020):

- Increase number of healthcare providers prepared to provide palliative care, which may require use of continuing education, certification programs, and so on.

- Provide ongoing education on care of the seriously ill.

- Develop more interdisciplinary/interprofessional team efforts with training as needed.

- Recruit from specialties, such as oncology, to develop more palliative care and end-of-life staff.

- Expand geriatric training.

- Expand training in these areas to home health care and understanding of the importance of home health care so that referrals are made.

Multiple Settings and Positions

The practice of nursing takes place in multiple settings, thus offering multiple job possibilities over a nurse's career span. Many nurses change their settings, positions, and specialties based on their interests and the jobs that they want to pursue during their careers. Some examples of these nursing settings and positions are provided here, and some are discussed in other chapters.

- Hospital-based or acute care nursing: This is the area that most students think of first when considering nursing positions. It is what is most frequently illustrated in the media (films, television, and so on). Within this setting, there are multiple specialty opportunities and clinical/management/education/research positions.

- Ambulatory care: This is a growing area for nurses. These settings are community based, such as clinics, private practice offices, ambulatory surgical centers (both freestanding and associated with hospitals), and diagnostic centers (both freestanding and associated with hospitals). There is greater expansion in this area today with more focus on public/community-based care. Nurses hold clinical and management positions in ambulatory care facilities.

- Public/community health: This area, which is growing rapidly, is an important clinical site for nursing students, and within this broad area are multiple opportunities. Examples include clinical/management/education positions in public/community health departments, clinics, school health, tuberculosis control centers, immunization clinics, home health care, substance use disorder treatment, mental health, occupational health, and more. Nurses may also be involved in the development and implementation of public policy at the local, state, and federal levels to improve health and healthcare quality. The experience with the COVID-19 pandemic may lead many nurses to view public/community health as an important specialty area to pursue.

- Home health care: This setting is very broad, in that numerous home healthcare agencies exist across the United States. Some are owned and managed by government agencies, such as city health departments, and others are owned and managed by other HCOs, such as hospitals, or may be part of national healthcare corporations, for-profit HCOs, or not-for-profit HCOs. Nurses in this specialty practice in the patient's home. They may also hold management positions within a home healthcare agency, and some nurses may even own home healthcare agencies. We typically think only about nurses and home healthcare aides making home visits. Historically, physicians also made these visits, but this became less common. Today, these visits have increased in some areas, and there is even increased payment from Medicare (My Virtual Physician, 2022; Wasik, 2016). In addition, digital health, which expanded during the pandemic, has had an impact on increasing patient-provider encounters in the home. Another new perspective that influences health services for the older adult is referred to as “Aging in place.” This approach helps older adults stay in their homes as long as possible, but for this to be effective, there must be access to healthcare services when needed. With new technology, we can do much more in the home and communicate with patients to monitor their status, as discussed in the chapter on HIT and medical technology. APRNs may also practice in the home setting, providing more expanded nursing services.

- Hospice and palliative care: This type of setting may be partnered with home health care, or it may be a freestanding separate service. Hospice and palliative care can also be associated with an inpatient unit that is either part of a hospital system or a long-term care facility. Hospice care has a special mission to engage patients, families, and significant others in the care process during this critical time and make the patient as comfortable as possible while meeting the patient's wishes. Palliative care or comfort care is also used when a life-threatening condition is present that may or may not result in death. Many acute care hospitals now have palliative care teams that provide support to the patient, family, and the staff who care for these patients daily.

- Nurse-managed health clinics (NMHCs): The NMHC is a newer clinic model. These clinics are community-based, primary healthcare services that operate under the leadership of an APRN and focus on health education, health promotion, and disease prevention (Dols, DiLeo, & Beckmann-Mendez, 2021). NMHCs are not-for-profit organizations and typically use a sliding scale for payments. The population targeted by these clinics is usually the underserved. They may be classified as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) (FQHC, 2020; Kovner & Walni, 2010). Since 2010, the number of FQHCs has grown. In 2012, the National Nurse-led Care Consortium (NNCC, 2023) was formed. This is a nonprofit member association that now represents more than 250 NMHCs throughout the United States. These clinics focus on delivering care in neighborhoods, connecting social service delivery needs and resources, and partnering with the community to advance health equity. The HHS provides support and resources for health centers and is supportive of providing nursing care to diverse populations with varied needs (HHS, HRSA, 2023a).

- Retail clinics: A healthcare delivery growth area is retail clinics. These are clinics located in retail areas, such as in a pharmacy, a large grocery store, or a mall. The goal is to provide the consumer with easy access to ambulatory care. Most of these clinics use APRNs as their primary care provider. Sometimes a for-profit corporation owns them, and others may be owned by academic health centers. It was thought that these clinics would reduce emergency department visits for low-acuity conditions; however, a 2016 study indicated that this was not necessarily true-there was a slight decrease in emergency department visits for patients with private insurance (Martsolf et al., 2016). A 2019 study indicated that there was some reduction in emergency department visits for flu symptoms when a retail clinic was nearby (Heath, 2019). The researchers in the 2016 study attributed their results to the fact that most retail clinics are in higher-income, suburban areas, and residents have health insurance so consumers may choose to go to other types of providers. These clinics may also serve as a source of referrals to a medical center. We need more data over time to understand the outcomes of this type of ambulatory care setting. We do not yet have data indicating if these clinics had an impact on COVID-19 testing, vaccination, and care.

- School nursing: This setting is part of public/community health nursing. The focus is on the provision of healthcare services within schools. The role of the school nurse is changing. Some schools have very active clinics where nurses provide a broad range of healthcare services to students. Pediatric APRNs may be more involved in school clinics that provide more expanded services. School nursing services have been very important in coping with the issues of opening schools during the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuring students, faculty, and staff are safe and receive timely assessments if sick.

- Occupational health: This is a unique setting for nursing practice. Nurses who work in this area provide healthcare services in occupational or work settings. They provide emergency care and direct care, including assessment, screenings, preventive care, and health and safety education, and may work with employer management to develop and ensure a safer work environment. They also initiate referrals for additional care. Some schools of nursing offer graduate degrees in this area. This, too, has been an important care resource during the pandemic if businesses were open, ensuring employee safety and assessment when needed.

- Digital health/telehealth/telemedicine: Nurses work in digital health by monitoring patients, providing patient and family education, and providing care by guiding the patient. Home health care may also use this method. This is considered a care service area that will increase, and it increased during the COVID-19 pandemic with more physicians using this method. As discussed in this text, this is a rapidly expanding area and will offer many opportunities for nurses.

- Parish nursing: Parish nursing takes place in a faith-based setting, such as a church or other religiously affiliated institution. The nurse is often a member of the faith-based institution. Healthcare services might include screenings and prevention, health education, and referral services for the members of the institution (Registered Nurse.org, 2023).

- Office-based nursing: Nurses work in physician practices. Some of the nursing staff may be APRNs, though most will not be. Some APRNs may have their own practices. Depending on the nurses' level of education, the nurses provide assessment and direct services, assist the physician, monitor and follow up with patients, and teach patients and families. APRNs provide more advanced nursing care in this setting.

- Extended care and long-term care: Many nurses work in this area. With the aging population increasing, nursing staff needs will increase. Positions may be in residential or community-based centers. Nurses provide assessment, direct care, and support to patients and support and education to families. They also hold management positions in these HCOs, which in some cases are residential facilities with associated healthcare support services that provide care on a continuum.

- Management positions: Nurse managers are found in all HCOs. The key responsibilities of this functional position are staffing, recruitment, and retention of staff; planning, budgeting, and staffing; supervising; QI; supporting EBP; staff education; and ensuring the overall functioning of the nurse manager's assigned unit, division, or department.

- Nursing education (academic and staff education): This is a functional position. Nurses hold academic faculty positions in nursing education programs and may also serve in research and administrative positions in academic institutions. Nurses also hold positions in staff development or staff education within HCOs, focusing on staff orientation, ongoing staff education, and maintenance of continued competencies.

- Nursing research: Nurses are involved in research in HCOs, academic institutions, and in the public/community arena. They fill many research roles, including serving as the primary investigator designing and leading research studies, collecting data, and analyzing data. Some HCOs refer to this role as a nurse scientist. In addition to participating in nursing research, nurses also participate in interprofessional research. Because research provides important evidence for EBP, nurses contribute to the expansion and use of EBP.

- Informatics/health information technology: Nurses are active in HIT as a specialty and as a part of their other responsibilities. A nurse might serve on the HIT committee or participate in planning for the implementation of an EMR. If the nurse has advanced IT expertise, the nurse may lead or help with major organizational HIT planning, implementation, and evaluation. Additional content explaining this role and preparation is discussed in this text's content about HIT. It is an important new role for nurses and HCOs.

- Nurse entrepreneurship: Nurses may serve as consultants or own a healthcare-related business. Some may be involved in developing new healthcare products or in technology development, including computer products. Nurses also serve as consultants to HCOs and nursing education programs on a variety of issues. Most nursing students do not know much about this area because it is a less common role for nurses; however, it is likely that this area will expand in the future.

- Nurse navigator: This nurse helps a patient and family effectively access and utilize the healthcare system. HCOs may use different titles for a nurse who fulfills these functions (Devine, 2017). The nurse may coordinate care among several professions or provide a bridge between transitional care settings. For example, the patient who has cancer and has been discharged home may require care coordination between the acute care facility and oncology and radiology services. The patient may also need home visits. The nurse navigator helps arrange services and coordinates the care. Some HCOs use case managers for this purpose, as do insurers.

- Legal nurse consultant: This nurse usually has completed additional coursework related to healthcare legal issues, and the nurse may even be certified in this area. The legal nurse consultant works with attorneys and provides advice about health issues, reviews medical records and other documents, and assists with planning legal responses. Some nurse legal consultants are hired by HCOs to assist their attorneys and participate in risk management functions. Nurses may serve as expert witnesses providing expert testimony for cases. Some nurses are also attorneys and thus function in a dual role in healthcare legal issues.

It is unknown what the future holds for new healthcare settings or new roles, but nursing history demonstrates that the likelihood of new roles emerging is high. In an interview Porter-O'Grady, a nursing leader and expert in professional issues, commented that mobility and portability would become very important in techno therapeutic interventions, and this has now occurred (Saver, 2006). Technology is extending into patients' lives, and the settings in which care is received are less directly connected to hospitals. Others suggested that as patients demanded more control as consumers, more self-diagnostic tests would be developed (Saver, 2006). This has also occurred; for example, there are apps to monitor and identify medical problems or monitor diet or exercise, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been greater use of home testing for the virus. New roles for nurses, in turn, have emerged to support changes, such as more active roles in positions concerned with healthcare quality, in pharmaceutical companies, as nurse practitioners in clinics, managing research and development departments associated with equipment or biomedical companies, working in or leading medical homes, support and development of HIT, and in counseling. Change continues, with more expected in the future, and it will require greater nursing leadership competency.

Nursing Specialties

Nursing specialties are part of the profession and expand professionalism. There are numerous general nursing specialties, such as maternal-child (obstetrics)/women's health, nurse-midwifery, neonatal, pediatrics, emergency, critical care, ambulatory care, public/community health, home health care, hospice, surgical/perioperative, anesthesia, psychiatric/mental health/behavioral health, management, legal nurse consulting, and many more. There are also subspecialties, such as diabetic care, wound care, and renal dialysis. The most important reason specialties develop is to meet the need for focused practice experience and ensure that nurses receive the necessary education to provide specialized nursing. All specialty nursing is based on the core general nursing knowledge and competencies. The same specialty might be offered in multiple settings-for example, a certified nurse-midwife (CNM) might work in hospitals in labor and delivery, a private practice with obstetricians, clinics, freestanding delivery centers, patients' homes, or an APRN private practice providing nurse-midwifery services.

There are two ways to view a specialty. One view is based on a nurse who works in a specialty area and claims it as his or her specialty (for example, the nurse works in a mental health unit and is then considered a psychiatric/mental health nurse). A second view, combined with the first, is that the nurse has additional education and possibly certification in a specialty. For example, the psychiatric/mental health nurse may have a master's degree in psychiatric-mental health nursing and is also certified in this specialty. The key to effective functioning as a specialty nurse is making a commitment to gain additional education in the specialty. This also includes continuing professional education and may include certification.

As discussed in other content in this text, there are many titles in nursing, but they do not necessarily indicate a nurse's specialty. These titles are APRN, clinical nurse specialist (CNS), clinical nurse leader (CNL), and doctor of nursing practice (DNP) (titles and education discussed in other content in this text). The titles for CNM and certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNA) make their specialties clear in their titles (midwifery and anesthesia, respectively). An APRN may focus on one or more specialties, such as families, pediatric acute care, adult-gerontology primary care or acute care, pediatric primary care, neonatal care, and psychiatric-mental health. A CNL does not typically focus on a specific clinical group in the CNL degree program; instead, this is a functional role that may be used in any type of specialty area. For example, a CNL may hold a position in a medical unit, a pediatric unit, or a women's health unit. The CNS title is also a broader term, but the CNS master's degree focuses on a specific clinical area. However, it is not a common title today due to the increased use of APRNs and CNLs. Specialty education at the graduate level and certification support professionalism in nursing and help to ensure that nursing remains a profession. As discussed in education content, many of these positions are transitioning to requiring an entry-level DNP degree rather than a master's degree. In this chapter, which is focused on leadership and the future of the profession, all these roles are important.

Nurse leaders must continually support staff and the need for professionalism within the work setting. They do this by recognizing education and degrees through differentiated practice, encouraging ongoing staff education (continuing professional education and pursuit of additional academic degrees), ensuring that standards are maintained, working to increase staff participation in decision-making, helping staff who want to move into a management position accomplish this goal (for example, by directing staff to management-focused education to prepare for the role), and mentoring staff who want to pursue the management track. Nurse leaders also need to encourage staff to participate in professional organizations, publish in professional journals, attend professional conferences, submit abstracts for presentations, participate in EBP, QI, and research, and recognize staff accomplishments throughout the HCO.

Advanced Practice Registered Nurse: Changing Scope of Practice

The role of the APRN has expanded over time. For example, early in the development of this role, a review of research studies on APRNs indicated that “[n]urses' role in primary care has recently received substantial scrutiny, as demand for primary care has increased and nurse practitioners have gained traction with the public. Evidence from many studies indicates that primary care services, such as wellness and prevention services, diagnosis and management of many common uncomplicated acute illnesses, and management of chronic diseases, such as diabetes, can be provided by nurse practitioners at least as safely and effectively as by physicians” (Fairman et al., 2010, p. 280). The report The Future of Nursing also recommended increased expansion of nurses' scope of practice in primary care focused on advanced practice (IOM, 2011). Changes have occurred, but today one of the critical factors that limits nurse practitioners' scope of practice is state-based regulations (NCSBN, 2023a). Some approved legislation has had an impact on APRN scope of practice. One example is the movement to allow APRNs to sign home health plans of care and certify Medicare patients for home health benefits. These changes required legislation. President Trump signed the Home Health Care Planning Improvement Act of 2019 into law. This legislation, which is federal, impacts APRNs wherever they may practice with Medicare patients. This change improves the transition of care for patients by providing another option that supports timely and effective planning for patients (Donlan, 2020). Direct payment for nurse practitioners has been a long-term issue, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) now allows payment; however, there are other payers that may not provide this reimbursement.

As noted previously, there are several barriers that have prevented expansion of the role of nurse practitioners in primary care, particularly state laws that limit scope of practice and reimbursement policies. Some of these issues and actions taken to try and increase APRN scope of practice and reimbursement have increased professional tensions among nurse practitioners, physicians, and physician assistants. The CMS expansion of home healthcare actions by APRNs is an example of how policy solutions can address several issues that have long been barriers for APRNs by (1) removing unwarranted restrictions on scope of practice, (2) equalizing payment and recognizing nurse practitioners as eligible providers, (3) increasing nurses' accountability, (4) expanding nurse-managed centers, (5) addressing professional tensions and focus more on interprofessional teams, (6) funding education for the primary care workforce, and (7) funding research to examine outcomes (Naylor & Kurtzman, 2010, p. 898). It will take time to assess the outcomes of the CMS changes and determine if more changes are needed. All of this requires nursing leadership and advocacy to ensure that health policy considers what nurses may offer to patients and to healthcare delivery.

| Stop and Consider 3 |

|---|

| There are new nursing positions for APRNs but also for all nurses. |

Professional Practice

Today, professional practice models are viewed as having an impact both on the nursing profession and on quality care and provide a view of professional nursing for a group or an HCO-it may be a verbal description, visual, or both. “A professional practice model depicts nursing values and defines the structures and processes that support nurses to control their own practice and to deliver quality care.… A professional practice model provides the foundations for quality nursing practice” (Slatyer et al., 2016, p. 139). Some HCOs are developing, or have developed, their own professional practice models, but all should include a description of its “mission, vision, and values; how the organization manages and governs; how the organization cares for its patients; how various professions relate to one another; and how the organization develops and recognizes employees” (Robert & Finlayson, 2015, p. 26). Elements of a successful professional practice model should support expected nursing profession standards, differentiated practice, shared professional governance, collaboration, leadership, EBP and EBM, teams, and ongoing staff education. These elements are important topics and discussed in this text.

Differentiated Nursing Practice

Differentiated nursing practice is a factor in developing a professional practice model. The subject of the preferred degree for entry into nursing practice continues to be an issue in the nursing profession. As discussed in content on education, a decision was made in 1965 to establish the baccalaureate in nursing (BSN) as the nursing entry-level degree. Although this has yet to be fully implemented, it has increased. The emphasis on the BSN degree by some hospitals as part of the Magnet Recognition Program® has made a difference. Having an all-BSN staff is not required but rather encouraged that these hospitals support this level of education. Consequently, these HCOs usually have more registered nurses (RNs) with BSN degrees. Many studies and papers (Boston-Fleischhauer, 2019; Harrison et al., 2019; Kutney-Lee et al., 2016; Blegen et al., 2013; McHugh et al., 2013; Aiken et al., 2008; Friese et al., 2015) indicate that there is a positive impact on patient care when more RNs have a BSN degree, and this type of research result influenced this change. We are seeing more students in BSN programs and more nurses returning to complete a BSN degree.

Graduates from all types of nursing programs take the same licensure exam, and this complicates the differentiated practice issue. RN licensure is the same for all nursing graduates regardless of the type of degree earned. This is not a new topic-in 1990, Boston defined differentiated nursing practice as “a philosophy that focuses on the structuring of roles and functions of nurses according to education, experience, and competence” (p. 1). This does not mean that a graduate from one program is necessarily better than another because many individual factors determine effectiveness and competence; rather, it indicates that graduates from each program enter practice having completed a curriculum associated with a level of education and related competencies. Having a BSN degree may impact job opportunities. “A 2022 AACN survey of 646 schools of nursing found that 27.7% of hospitals and other healthcare settings require new hires to have a bachelor's degree in nursing (BSN). Additionally, 71.7% of employers are expressing a strong preference for BSN program graduates” (AACN, 2023a).

Differentiated practice continues to be an issue in the profession, and it needs to be addressed more in nursing policies and application to professional practice models, which may identify required levels of education and competency. With AACN research identifying a correlation between BSN-educated nurses and improved patient outcomes, this supports its efforts to encourage “employers to foster practice environments that embrace lifelong learning and offer incentives for registered nurses (RNs) seeking to advance their education to the baccalaureate and higher degree levels. We also encourage BSN graduates to seek out employers who value their level of education and distinct competencies” (AACN, 2022a). Many employers do not formally recognize a nurse's degree, for example, it is rarely noted on employee identification badges, and if noted, the degree designation is difficult to read on small name badges. Patients and many other staff do not know about nursing degrees and roles-they group all nurses together into the RN group. Another issue is that salaries are often not based on a nurse's education level unless it is a graduate degree, although they should be. Much needs to be done by the profession to address this area of concern, and this requires professional leadership.

Examples of Professional Practice Models

Why does an HCO need a professional practice model for nursing? When the Magnet Recognition Program® was developed, the description of the Magnet forces and the Magnet model provided the rationale for this program as: “Conceptual models provide an infrastructure that decreases variation among nurses, the interventions they will choose, and, ultimately, patient outcomes. Conceptual frameworks also differentiate forward thinking organizations from those where nursing has less of a voice” (Kerfoot et al., 2006, p. 20). These forward-thinking HCOs also tended to have a professional rather than technical view of nursing with nursing leadership recognizing this view. A model offers nurses “a consistent way of framing the care they deliver to patients and their families” (Kerfoot et al., 2006, p. 21). The Forces of Magnetism for Magnet hospitals now emphasize the need for HCOs to implement a professional practice model. The Magnet Recognition Program®, which is a nursing practice model, is discussed later in this chapter.

Examples of professional practice models are found in Figures 14-1, 14-2, 14-3, 14-4, 14-5, and 14-6. Some of these models are no longer used, but it is important to understand their evolution; sometimes, they are used again or revised. The functional model is used less today, although the total care model may be used in critical care. The primary care nursing model was very popular in the 1980s but less so now because it requires a greater number of RNs. Some HCOs, however, still use this model, but usually as an adaptation of the original model.

Figure 14-1 Nursing leadership.

A word cloud highlights terms related to nurse leadership. Prominent terms include nurse leadership, vision, goal, business, lead, team, management, success, strategy, career, teamwork, chief, and communication.

© Sharaf Maksumov/shutterstock

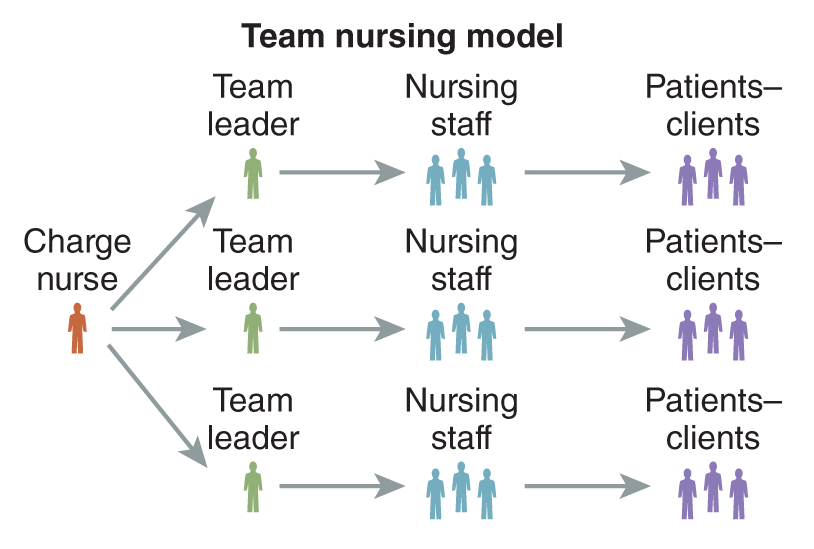

Figure 14-2 Team nursing model.

A hierarchical structure of the team nursing model outlines roles and relationships.

The Charge nurse directs three team leaders, each of whom manages a group of nursing staff. Arrows indicate the flow of responsibilities from the Charge nurse to team leaders, then from team leaders to nursing staff, and finally from nursing staff to patients endash clients. Each role is visually represented by an icon.

Hansten, R. I., & Jackson, M. (2011). Clinical delegation skills: A handbook for professional practice. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

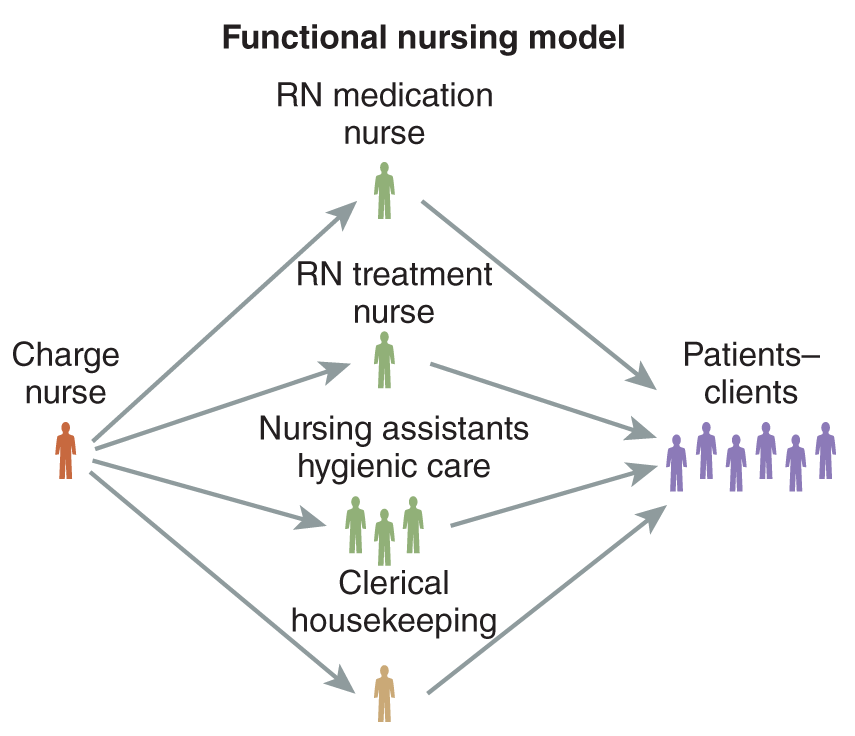

Figure 14-3 Functional nursing model.

A hierarchical structure of the functional nursing model outlines roles and responsibilities.

The Charge nurse directs tasks to the R N medication nurse, R N treatment nurse, nursing assistants for hygienic care, and clerical housekeeping. Arrows indicate the flow of responsibilities from the Charge nurse to these roles and then to patients endash clients. Each role is visually represented by an icon.

Hansten, R. I., & Jackson, M. (2011). Clinical delegation skills: A handbook for professional practice. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

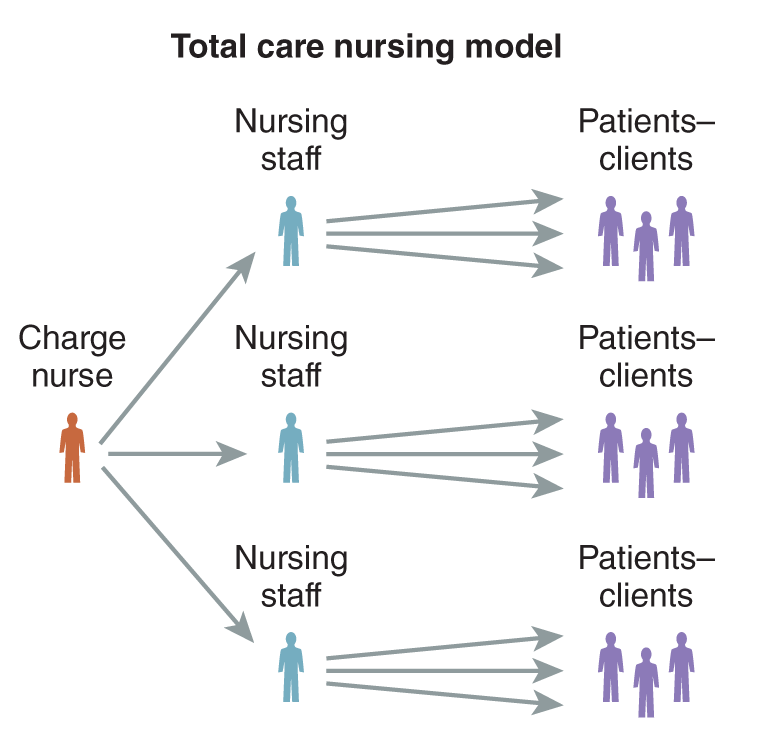

Figure 14-4 Total patient care model.

A hierarchical structure of the total care nursing model outlines roles and responsibilities.

The Charge nurse directs three groups of nursing staff, each group taking care of their assigned patients endash clients. Arrows indicate the flow of responsibilities from the Charge nurse to each group of nursing staff, and then from each group of nursing staff to their respective patients endash clients. Each role is visually represented by an icon.

Hansten, R. I., & Jackson, M. (2011). Clinical delegation skills: A handbook for professional practice. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

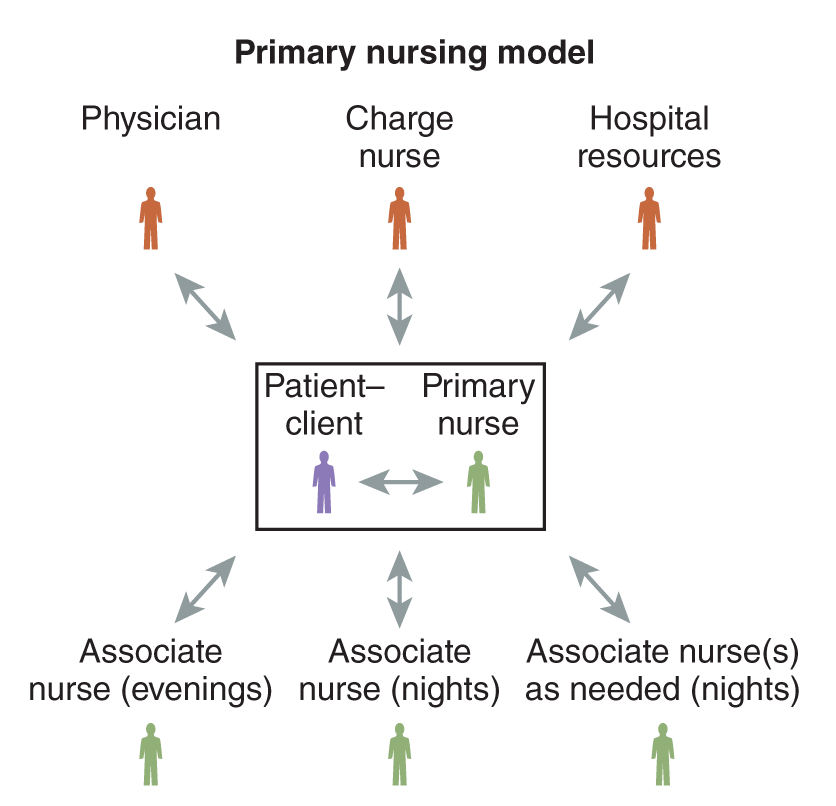

Figure 14-5 Primary care model.

A hierarchical structure of the primary nursing model outlines roles and responsibilities.

The primary nurse and patient endash client with bidirectional arrows are depicted at the center. Surrounding them are the physician, charge nurse, and hospital resources, all connected with bidirectional arrows to the primary nurse. Below are associate nurses for evenings, nights, and as needed at nights, all connected with arrows to the primary nurse. Each role is visually represented by an icon.

Hansten, R. I., & Jackson, M. (2011). Clinical delegation skills: A handbook for professional practice. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

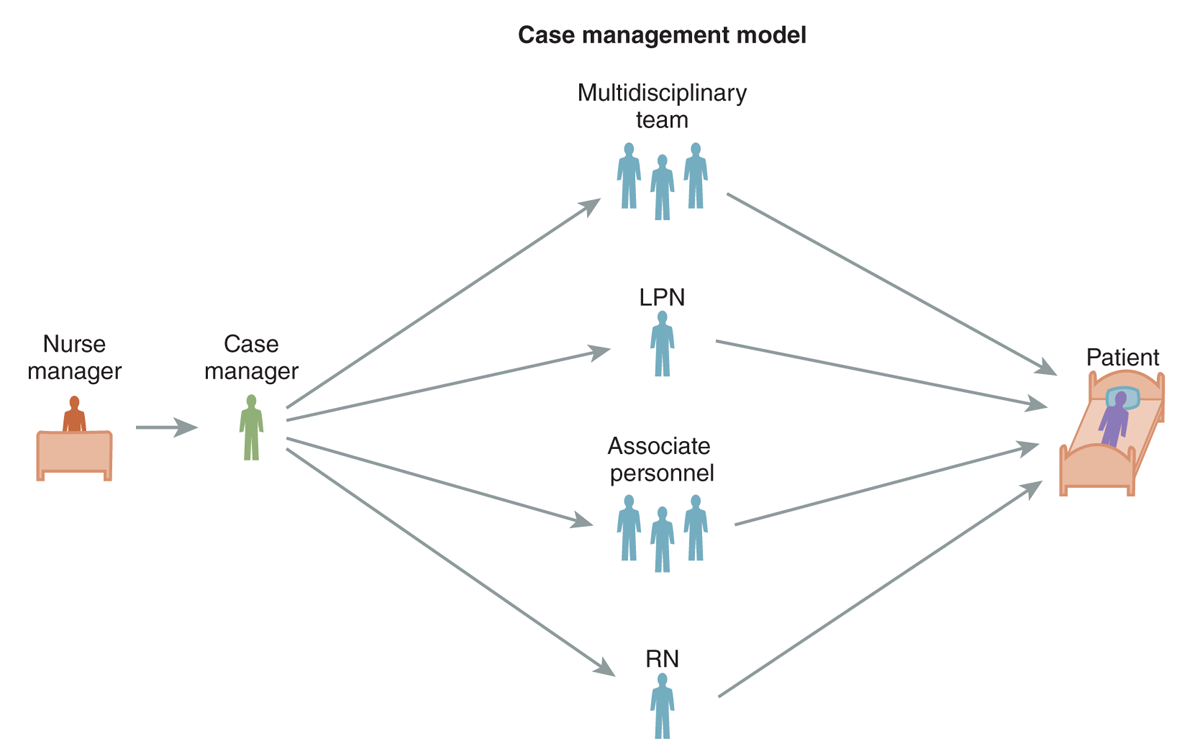

Figure 14-6 Case management model.

A hierarchical structure of the case management model outlines roles and responsibilities.

At the left is the nurse manager, who directs the case manager. The case manager oversees a multidisciplinary team, L P N, associate personnel, and R N. Arrows indicate the flow of responsibilities from the case manager to these roles, and then from these roles to the patient. Each role is visually represented by an icon.

Hansten, R. I., & Jackson, M. (2011). Clinical delegation skills: A handbook for professional practice. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses' Synergy Model for Patient Care is another example of a current nursing model. This model's core premise is closely related to the healthcare professions and nursing competencies, particularly PCC, as it focuses on patient and family needs as the drivers of the nurse's characteristics and competencies (American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 2023). The model identifies key patient characteristics as resiliency, vulnerability, stability, complexity, resource availability, participation in care, participation in decision, and predictability, and the key nurse competencies are clinical judgment, advocacy, caring practices, collaboration, systems thinking, response to diversity, clinical inquiry, facilitation of learning, and clinical inquiry (innovator/evaluator) (American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 2023; Harden & Kaplow, 2016). This model can be applied to all types of units, not just critical care.

Innovative and newer professional practice models have common elements (Kimball et al., 2007). Specifically, they include an elevated RN role; greater focus on the patient; efforts to improve patient transition and handoff to decrease errors and make the patient more comfortable; leveraging of technology to enable a care model design, such as EMRs, robots, barcoding, cell phone communication, and more; and greater emphasis on results or outcomes. The healthcare professions and nursing competencies also provide an effective start for a professional practice model (IOM, 2003b).

| Stop and Consider 4 |

|---|

| Differentiated practice has an impact on every nurse. |

Impact of Legislation/Regulation/Policy on Nursing Leadership and Practice

Effective healthcare legislation, regulations, and policies should include nurses who work collaboratively with stakeholders in shaping health policy through legislation and regulation. Nurses are involved and will continue to be involved at the local, state, national, and international levels as noted in previous content.

An example of the need for nursing profession involvement is policies that are related to nursing staffing. Over the last decade, many agencies, through the establishment of state workforce centers, have examined the impact of state legislation and regulation on nursing supply and demand. State workforce centers focus on maintaining an adequate supply of qualified nurses within a state to meet healthcare needs (demand), providing analysis and strategies to address unmet needs (National Forum of State Nursing Workforce Centers, 2023). This initiative has been more successful on the state level than the federal/national level, though we need both perspectives to better prepare to meet staffing needs for all healthcare professionals. The National Health Care Workforce Centers initiative is designed to focus on the future needs of the workforce, using data collection and analysis to better understand the problem and develop strategies to resolve problems, such as the impact on nursing education planning. Most states have a state-focused workforce initiative.

In addition, COVID-19 has made it very clear that staffing issues during a crisis of this magnitude have a major impact on the public's health and require a national perspective (HHS, CDC, 2021). It is not yet clear what the long-term impact of our experiences with COVID-19 will be on staffing (NCSBN, 2020). In a December 7, 2020, statement the National Council for State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) identified concerns about workforce issues and COVID-19 care and associated its views with those of multiple nursing organizations (2020) and with federal government concerns and initiatives:

- According to recent hospital data submitted to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, thousands of hospitals nationwide are experiencing a “critical staffing shortage” of healthcare workers, with that number expected to grow. The nursing workforce is particularly depleted and maldistributed according to media reports, creating shortages in areas that are now being hardest hit by COVID-19.

- These healthcare workforce staffing shortages are particularly acute in rural areas that are currently experiencing an influx of COVID-19 patients, resulting in a decrease in available nursing staff or, in some cases, filling rural hospitals to capacity. When rural hospitals lack the ability to provide care, patients seek care in more urban hospitals, putting a greater strain on services and an already depleted nursing workforce.

- Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projected RN employment would increase by 7% and APRN employment by 45% as of 2029. While research can review past nursing workforce numbers and project future participation, no mechanisms measure the current nursing workforce participation in the COVID-19 response.

There is no doubt that quality care is a major issue addressed by healthcare legislation. Nurses need to be involved in these initiatives because they directly affect patient care every day in multiple settings, and they have important expertise to share. Healthcare legislation at the state level is also important to nursing. For example, many states have tried to pass legislation related to mandatory overtime and staff-patient ratios-and some states have already enacted this type of law. The use of required mandatory overtime was also an issue during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Congressional Nurses' Caucus is responsible for educating the U.S. Congress about nursing (AONL, 2023). It is important that state and federal legislators understand the nursing profession and its importance to health and healthcare delivery in the United States. There are approximately 100 nurses who serve in the U.S. Congress and in state legislatures. More nurses are needed to run for office at the local, state, and national levels. Nurses who have an interest in politics and health policy need to plan for this activity, particularly if they want to run for office in the future. This requires a career plan with a time frame, mentoring, and experience in political activities.

Regulation is also an important issue today as change occurs both within the healthcare system and within nursing, impacting policies as discussed in earlier content. One example is an initiative to change regulations related to APRNs, focusing on changes to allow APRNs to practice independently of physicians, when appropriate. Many states are examining such changes, and some are enacting them.

| Stop and Consider 5 |

|---|

| To improve health care, we need more nursing leadership in health policy. |

Economic Value and the Nursing Profession

Salaries and benefits, which vary across the United States, have long been a concern of nurses. Some nurses have unionized to get better salaries and benefits and to have more say in the decision-making process in the work setting. The nursing profession has yet to develop effective methods to determine their value in the reimbursement process and implications for HCO budgets, and it is important to solve this problem. How do nurses describe the value of nursing services? How do nurses identify the costs of nursing services? Some efforts have been made to accomplish this, but there is much more to do. Within the fragmented healthcare system, nursing contributions are even more difficult to identify. Most HCO accounting systems have not been able to capture or differentiate the economic value provided by nurses (IOM, 2010).