In the fall of 2016, the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) celebrated its 30th anniversary with activities based on the theme of “Advancing Science, Improving Lives. A Window to the Future” (NINR, 2015). In 2023, the NINR continued supporting nursing knowledge through its 2022-2026 strategic plan vision: “supporting science that advances our mission: to lead nursing research to solve pressing health challenges and inform practice and policy-optimizing health and advancing health equity into the future” (NINR, 2022). Nursing has developed into a profession that now has greater emphasis on research and the application of research. This chapter focuses on knowledge representing the science of nursing and the art and caring of nursing. We must always consider both aspects of the profession. A 2006 publication by Nelson and Gordon, The Complexities of Care: Nursing Reconsidered, expanded on this topic, laying the groundwork for greater appreciation of nursing practice. The authors stated, “Because we take caring seriously, we (the authors) are concerned that discussions of nursing care tend to sentimentalize and decomplexify the skill and knowledge involved in nurses' interpersonal or relational work with patients” (p. 3). Nelson and Gordon make a strong case that there is an ongoing problem of nurses devaluing the care they provide, particularly regarding the required knowledge component of nursing care and technical competencies needed to meet patient care needs, although caring is an important part of the process-both aspects relate to the goal of providing quality care. (Refer to the Connect to Information for EBP at the end of the chapter for an examination of caring as a nursing concept.) This chapter explores how knowledge and caring relate to nursing practice. Both must be present to ensure nursing care quality. Content includes the effort to define nursing, knowledge and caring, competency, nursing scholarship, major nursing roles, and leadership.

Nursing: How Do We Define It?

Defining nursing is relevant to this chapter and requires further exploration. A historical perspective is found in Chapter 1, “Professional Nursing: History and the Development of the Nursing Profession.” Can nursing be defined, and if so, why is it important to define it? Before this discussion begins, you should review your personal definition of nursing that you considered with the content found in the chapter on history. You may find it strange to spend time defining nursing, but the truth is, there is no universally accepted definition held by healthcare professionals and patients. A common approach to developing a definition is to describe what nurses do; however, this approach leaves out important aspects and essentially reduces nursing to tasks. Diers noted that even Florence Nightingale's and Virginia Henderson's definitions were not definitions of what nursing is but more of what nurses do. More consideration needs to be given to (1) what drives nurses to do what they do or why they do what they do (rationales, evidence-based practice [EBP]) and (2) what is achieved by what they do or the outcome (Diers, 2001). Henderson's definition focused more on a personal concept of nursing rather than a true definition. Henderson even said that what she wrote was not a complete definition of nursing (Henderson, 1991). Diers also commented that there really were no complete definitions for most disciplines. Yet nursing is still concerned with its definition. Having a definition serves several purposes that really drive what that definition will look like (Diers, 2001, p. 7):

- Provides an operational definition to guide research

- Acknowledges that changing laws requires a definition that will be politically accepted-for example, in relationship to a Nurse Practice Act

- Convinces legislators about the value of nursing-for example, to gain funds for nursing education

- Explains what nursing is to consumers/patients (although no definition is totally helpful because patients/consumers respond to a description of the work, not a definition)

- Explains to others, in general, what one does as a nurse, which often represents a personal description of nursing

A definition is helpful in guiding content for the nursing curriculum, but nursing has been taught for years without a universally accepted definition. As mentioned in other content in this text, the American Nurses Association (ANA) defines nursing as “the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and abilities, prevention of illness and injury, alleviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human response, and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, communities, and populations” (2021, p. 88). Some of the critical terms in this definition include health promotion, health, prevention of illness and injury, illness, injury, diagnosis, plan, treatment, and advocacy, which are discussed in the ANA standards. Essential features of professional nursing practice are identified from the definition of nursing's focus on caring and health, providing individualized nursing care using the nursing process, coordination of care supported by relationships, and ensuring a professional work environment combined with providing quality nursing care to meet best outcomes (ANA, 2021, pp. 7-9). Knowledge and caring are the critical dyad in any description or definition of nursing, and both relate to nursing scholarship and leadership and are integrated into the previously mentioned features.

As part of a project to define the work of nursing, the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA, 2023a) described nursing diagnoses and developed the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) (University of Iowa, 2023a) and the Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) (University of Iowa, 2023b). These descriptions serve as building blocks of nursing practice theory and emphasize that “rather than debating the issues of definition, nursing will be better served by focusing those energies on its science and the translation of the science of nursing practice” (Maas, 2006, p. 8). In summary, there are three conclusions about defining nursing that are important to consider: (1) No universally accepted definition of nursing exists, although several definitions have been developed by nursing leaders and nursing organizations; (2) individual nurses may develop their own personal description of nursing to use in practice; and (3) a more effective focus is the pursuit of nursing knowledge to build nursing scholarship. The first step is to gain a better understanding of knowledge and caring in relation to nursing practice. NANDA International states: “Implementation of nursing diagnosis enhances every aspect of nursing practice, from garnering professional respect to assuring consistent documentation representing nurses' professional clinical judgment, and accurate documentation to enable reimbursement. NANDA International exists to develop, refine, and promote terminology that accurately reflects nurses' clinical judgments” (NANDA, 2023b).

| Stop and Consider 1 |

|---|

| Your personal definition of nursing is as important as a formal professional definition of nursing. |

Knowledge and Caring

Understanding how knowledge and caring form the critical dyad for nursing is essential to providing effective quality care. Knowledge is specific information about something, and caring is behavior that demonstrates compassion and respect for another, which should support diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). These are very simple definitions, and the depth of nursing practice goes beyond basic knowledge and the ability to care. Nursing encompasses a distinct body of knowledge coupled with the art of caring. As stated by Butcher (2006), “A unique body of knowledge is a foundation for attaining the respect, recognition, and power granted by society to a fully developed profession and scientific discipline” (p. 116).

Knowledge

Knowledge can be defined and described in several ways. There are five ways of understanding how one knows something. A nurse might use all or some of these ways of knowing when providing care (Cipriano, 2007):

- Empirical knowing focuses on facts and is related to quantitative explanations-predicting and explaining.

- Ethical knowing focuses on a person's moral values-what should be done.

- Personal knowing focuses on understanding and actualizing a relationship between a nurse and a patient, including knowledge of self (nurse).

- Aesthetic knowing focuses on the nurse's perception of the patient and the patient's needs, emphasizing the uniqueness of each relationship and interaction.

- Synthesizing, or pulling together the knowledge gained from the other types of knowing, allows the nurse to understand the patient better and to provide higher quality care.

The ANA (2021) identifies 18 standards of practice focused on the following, and many are related to the knowledge base for nursing practice, including both theoretical and evidence-based knowledge:

- Assessment

- Diagnosis

- Outcomes identification

- Planning

- Implementation

- Evaluation

- Ethics

- Advocacy

- Communication

- Collaboration

- Leadership

- Education

- Scholarly inquiry

- Quality of practice

- Professional practice evaluation

- Resource stewardship

- Environmental health

The ANA standards require basic knowledge that every nurse should have to practice. Nurses use this knowledge in their practice and implement the standards, but they also must integrate this knowledge as they collaborate with patients and the healthcare team to assess, plan, implement, and evaluate care. The newest version of the standards also supports the need for DEI, health literacy, and other related information discussed throughout this text.

Knowledge Management

Knowledge work is a critical component of healthcare delivery today, and nurses are knowledge workers. A systematic review of 18 studies noted that knowledge management is facilitated by “an organization culture that supports learning, sharing of information and learning together. Leader commitment and competency were factors related to leadership facilitating knowledge management” (Lunden et al., 2017, p. 407). Knowledge management includes both routine work (such as taking vital signs, administering medications and procedures, ensuring dietary needs, and walking a patient) and nonroutine work, which involves exceptions, requires judgment and the use of knowledge, and may be confusing or not fully understood. In a knowledge-based environment, a person's title is not as important as the person's expertise, and the use of knowledge and learning are important. This sharing of information is related to evidence-based practice. Knowledge workers actively use the following skills:

- Communication

- Collaboration

- Teamwork

- Coordination

- Analysis

- Critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and judgment

- Evaluation

- Flexibility

Knowledge workers recognize that change is inevitable, and the best approach is to be ready for change and view it as an opportunity for learning and improvement. Nurses use knowledge daily in their work. They work in an environment that expects healthcare providers to use the best evidence in providing care. “Transitioning to an evidence-based practice requires a different perspective from the traditional role of nurse as ‘doer' of treatments and procedures based on institutional policy or personal preference. Rather, the nurse practices as a ‘knowledge worker' from an updated and ever-changing knowledge base” (Mooney, 2001, p. 17). The knowledge worker focuses on acquiring, analyzing, synthesizing, and applying evidence to guide practice decisions (Dickenson-Hazard, 2002). The knowledge worker also uses synthesis, competencies, multiple intelligences, a mobile skill set, outcome practice, and teamwork, as opposed to the old skills of functional analysis, manual dexterity, fixed skill set, process value, process practice, and unilateral performance (Albert et al., 2020). This nurse is a clinical scholar. Employers and patients should value a nurse for what the nurse knows and how this knowledge is applied to meet patient care outcomes-not just for technical expertise and caring, although these aspects of performance are also important (Kerfoot, 2002). The American Organization for Nursing Leadership (AONL) includes knowledge of the healthcare environment in its competencies for nurse leaders: Nurse executives, nurse managers, and clinical nurse leaders in all areas of healthcare need to emphasize greater application of knowledge in postacute care (public health/community systems) and population health (AONL, 2023). The experience of the COVID-19 pandemic made this need more evident.

This change in a nurse's work was also reflected in the Carnegie Foundation's report on nursing education, as reported by Patricia Benner and colleagues (2010). The report suggested that instead of focusing on content, nurse educators should focus on teaching nurses how to access information, use and manipulate data (such as data from patient information systems), and document effectively in the electronic interprofessional format-using knowledge to improve practice and care. These are critical competencies to better ensure that nurses maintain knowledge of new information, apply it to nursing practice, and support continuous quality improvement.

Critical Thinking and Clinical Thinking and Judgment: Impact on Knowledge Development and Application

Critical thinking, reflective thinking, and intuition are different approaches to thinking, but they can be used in combination. Nurses use them to explore, understand, develop new knowledge, and apply knowledge as evidence for best practice and caring in the nursing process. Experts, such as Dr. Benner, suggested that we often use the term critical thinking, but there is high variability and little consensus on what constitutes critical thinking (Benner et al., 2010). Clinical reasoning and judgment are also very important and include critical thinking, which is an element of effective nursing practice. The ANA standards state that the nursing process is a critical thinking tool but not the only one used in nursing (ANA, 2021). This skill emphasizes purposeful thinking rather than sudden decision-making that may not be based on thought and knowledge. Alfaro-LeFevre (2014) identified four key critical thinking components:

- Critical thinking characteristics (attitudes/behaviors)

- Theoretical and experiential knowledge (intellectual skills/competencies)

- Interpersonal skills/competencies

- Technical skills/competencies

In reviewing each of these components, one can easily identify the presence of knowledge, caring (interpersonal relationships, attitudes), and technical expertise. The nursing process (assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation) applies these components and is discussed in more detail later in this text.

Critical thinking requires nurses to generate and examine questions and problems, use intuition, examine feelings, and clarify and evaluate evidence. It means being aware of change and willing to take some risks. Critical thinking allows the nurse to avoid using dichotomous thinking-seeing situations as either good or bad or black or white. This type of thinking limits possibilities and clinical choices for patients (Finkelman, 2001).

Critical thinking skills that are important to develop include affective learning; applied moral reasoning and values (relates to ethics); comprehension; application, analysis, and synthesis; interpretation; knowledge, experience, judgment, and evaluation; learning from mistakes; and self-awareness (Finkelman, 2001). A person uses four key intellectual traits in critical thinking, which students should develop, and these are important throughout a nurse's practice experiences (Paul, 1995).

- Intellectual humility: Willingness to admit what one does not know. (This is difficult to do, but it can save lives. A nurse who cannot admit that he or she does not know something and yet proceeds with care activities is taking a great risk. It is important for students to be able to use intellectual humility as they learn about nursing.)

- Intellectual integrity: Continual evaluation of one's own thinking and willingness to admit when thinking is not adequate. (This type of honesty with self and others can make a critical difference in care.)

- Intellectual courage: Ability to face and fairly address ideas, beliefs, and viewpoints for which one may have negative feelings. (Students enter a new world when they begin their nursing education-the world of health care-and may experience confusing thoughts about ideas, beliefs, and viewpoints, and sometimes, their personal views may need to be put aside in the interest of the patient and quality care.)

- Intellectual empathy: Conscious effort to understand others by putting one's own feelings aside and imagining oneself in another person's place. (This is something that needs to be developed over time; some students come into nursing with this ability.)

Critical thinking also helps to reduce the tendency toward using dichotomous thinking and groupthink to avoid focusing on just two options. Dichotomous thinking is related to groupthink, which occurs when a group or team members think alike. While all team members might be working together smoothly, groupthink limits choices, discourages open discussion of possibilities, and diminishes the ability to consider alternatives and innovation. Problem-solving is not a critical thinking skill, but effective problem solvers use critical thinking. The following methods may be used to develop critical thinking skills (Finkelman, 2001, p. 196):

- Seek the best information and data possible to allow you to fully understand the issue, situation, or problem. Questioning is critical. Examples of some questions that might be asked are: What is the significance of ___? What is your first impression? What is the relationship between __ and __ ? What might be the impact on__ ? What can you infer from the information/data?

- Identify and describe any problems that require analysis and synthesis of information-thoroughly understand the information/data.

- Develop alternative solutions-more than two is better because this forces you to analyze multiple solutions even when you discard one of them. Be innovative and avoid proposing only typical or routine solutions.

- Evaluate alternative solutions and consider the consequences of each one. Can the solutions really be used? Do you have the resources you need? How much time will it take? How well will the solution be accepted? Identify the pros and cons.

- Decide, choosing the best solution, even though there is risk in any decision.

- Implement the solution but continue to question.

- Follow up and evaluate, integrate evaluation from the very beginning. Self-assessment of critical thinking skills is an important part of using critical thinking. How does one use critical thinking, and is it done effectively?

Reflective thinking needs to be a part of daily learning and practice. Critical reflective thinking requires that nursing students and nurses examine underlying assumptions and question or even doubt the arguments, assertions, or facts of a situation or case (Benner et al., 2008). This allows the nurse to better understand the patient's situation. Reflection is seen as a part of the art of nursing, which requires guidance to develop, for example, using it during simulation experiences to develop an understanding of the process and its impact: “All simulation-based learning experiences should include a planned debriefing session aimed toward promoting reflective thinking. Learning is dependent on the integration of experience and reflection. Reflection is the conscious consideration of the meaning and implication of an action, which includes the assimilation of knowledge, skills, and attitudes with pre-existing knowledge. Reflection can lead to new interpretations by the learner. Reflective thinking does not happen automatically, but it can be taught; it requires time, active involvement in a realistic experience, and guidance by an effective facilitator” (Decker et al., 2013, p. 526). Reflection helps nurses cope with unique situations.

The skills needed for reflective thinking are the same skills required for critical thinking-the ability to monitor, analyze, predict, and evaluate (Pesut & Herman, 1999) and to take risks, be open, and have imagination (Westberg & Jason, 2001). Faculty can assist students in using reflective thinking, as noted above, during simulated learning experiences and during other types of clinical experiences, enhancing student learning and encouraging students to use reflective learning skills independently. It is recommended that this process be done with faculty support so that students view the learning experience as an opportunity to improve and examine the experience from different perspectives (Decker et al., 2013). Some strategies that might be used to develop reflective thinking are keeping a journal (such as the Electronic Reflection Journal end-of-chapter activities), engaging in one-to-one dialogue with a faculty facilitator, joining in student team email or other electronic discussion, and participating in structured team forums in the classroom or online to help students understand how others examine an issue and learn more about constructive feedback. Ideally, the opportunity to develop these skills in an interprofessional student experience will support more effective interprofessional teamwork in practice. Reflective thinking strategies are not usually used for grading or evaluation but rather are intended to help students think about their own learning experiences in an open manner. This can then be used by the student in practice when it is important for individual nurses to examine their practice and outcomes.

Intuition is part of thinking. “Intuition is more than simply a ‘gut feeling,' and it is a process based on knowledge and care experience and has a place beside research-based evidence. Nurses integrate both analysis and synthesis of intuition alongside objective data when making decisions. They should rely on their intuition and use this knowledge in clinical practice as a support in decision-making, which increases the quality and safety of patient care” (Melin-Johansson et al., 2017, p. 3947). Nurses often experience intuition as they provide care-“I just have this feeling that Mr. Wallace is heading for problems.” It is hard to explain what this is, but it happens. The following are examples of thoughts that a person might have related to intuition (Rubenfeld & Scheffer, 2014):

- I felt it in my bones.

- I couldn't put my finger on why, but I thought instinctively I knew.

- My hunch was that …

- I had a premonition/inspiration/impression.

- My natural tendency was to …

- Subconsciously, I knew that …

- Without thought, I figured it out.

- Automatically, I thought that …

- While I couldn't say why, I thought immediately that …

- My sixth sense said I should consider …

Intuition is not science, but sometimes intuition can stimulate research and lead to greater knowledge and questions to explore. A student would not likely experience intuition about a patient-care situation, but over time, as nursing expertise is gained, the student may be better able to use intuition. Benner's (2001) work, From Novice to Expert, suggests that intuition for nurses is really focused on putting together the whole picture based on scientific knowledge and clinical expertise, not just a hunch. Intuition continues to be an important part of the nursing process (Benner et al., 2008).

Clinical reasoning and clinical judgment require more than recalling and understanding the content or selecting the correct answer; they also require the ability to apply, analyze, and synthesize knowledge (Del Bueno, 2005). It is now known to be of greater importance for the entry-level nurse “to organize complex information, think critically about numerous aspects of the patient situation, and then make correct decisions about how to proceed-they must demonstrate good clinical judgment skills” (Betts et al., 2019, p. 22). This process includes both deliberate, conscious decision-making and intuition, as mentioned earlier. “In the real world, patients do not present the nurse with a written description of their clinical symptoms and a choice of written potential solutions” (Del Bueno, 2005, p. 282). Beginning nursing students, however, are looking for a clear picture of the patient that matches what the student has read about in a text. This patient really does not exist, so critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and judgment become more important as the student learns to compare what might be expected with what is reality (Benner et al., 2010).

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) developed a clinical judgment measure model as described on its website (NCSBN, 2023). This model emphasizes needs and the clinical situation; recognizes cues and analyzes them to form hypotheses, with possible revision based on consideration of both environmental and individual patient factors; then the nurse takes actions and evaluates outcomes. The nursing process (assessment, analysis, planning, implementation, evaluation) underlies the process, though some nursing programs may use different terminology for the nursing process.

Sensemaking is a term that has been applied to “making sense of a problem.” It is part of using critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and judgment. You do this all the time in your daily life and then carry it forward into your nursing practice-solving a problem effectively requires understanding the situation. Individuals experience situations, confront gaps, understand and/or act, and then, after the experience, evaluate information that was used in the process. This is all done primarily unconsciously (Linderman et al., 2015). Data that are identified through observation, communication, and other methods are used to make sense of the experience or situation. From this, a nurse moves on to other experiences and may or may not reflect on past sensemaking or apply what was learned. Nurses also help others, such as their patients and their families or in the community populations that require health guidance, to understand what is happening to them. Sensemaking happens on the cognitive level as nurses use cognitive tools to understand and formulate a view, at the physical level as care is provided, and at the emotional level as nurses experience a situation and respond. Nursing leaders should make more use of sensemaking to build on their experiences and apply these to new experiences. Sensemaking is also associated with quality improvement and, thus, is important for nurses as they engage in quality improvement activities. “Safety interventions designed to be used by nurses should be developed with the dynamic, cognitive, sensemaking nature of nurses' routine safety work in mind. Being sensitive to the vulnerability of patients, respecting patient and family input, and understanding the consequences of dismissing patient and family safety concerns are critical to making sense of the situation and taking appropriate action to maintain safety” (Groves et al., 2020, p. 111).

Caring

There is no universally accepted definition for caring in nursing, but it can be described from four perspectives (Mustard, 2002). The first is the sense of caring, which is probably the most common perspective for students to appreciate. This perspective emphasizes compassion or being concerned about another person. In general, this type of caring may or may not require knowledge and expertise, but in nursing, effective caring requires both knowledge and expertise. The second perspective is doing for other people what they cannot do for themselves. Nurses frequently engage in this type of activity, and it requires knowledge and expertise to be effective. The third perspective is to provide care for health problems, and this requires knowledge of the problem, assessment, interventions, and so on, as well as expertise to provide the care. Providing wound care or administering medications is an example of this type of caring and is associated with the fourth perspective, “competence in carrying out all the required procedures,” to ensure the effective care is timely and provided with expertise (Mustard, 2002). For an action to be referred to as “caring,” all four types of caring are not usually applied at one time. Caring practices have been identified by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (2023) in the organization's synergy model for patient care, which focuses on reaching synergy when the needs and characteristics of patients and clinical unit or system are matched with the nurse's competencies. Caring is an important component of patient/person-centered care (PCC) and supports quality care through effective nursing competency.

Nursing theories often focus on caring. Theories are discussed later in this chapter, but it is important to note one theory that is known for its focus on caring-Watson's theory on caring. In 1979, Watson defined nursing “as the science of caring, in which caring is described as transpersonal attempts to protect, enhance, and preserve life by helping find meaning in illness and suffering, and subsequently gaining control, self-knowledge, and healing,” and this continues to be relevant today (Scotto, 2003, p. 289). Patients need caring. They feel isolated and are often confused by the complex medical system. Many patients have chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, arthritis, and cardiac problems, that require long-term treatment, and these patients need to learn how to manage their illnesses and be supported in the self-management process. Even many patients with cancer who have longer survival rates today are now described as having a chronic illness.

How do patients view caring? Patients may not see the knowledge and skills that nurses need, but they can appreciate when a nurse is there with them. The nurse-to-patient relationship can make a difference when the nurse uses caring consciously and focuses on PCC. As discussed in this text, PCC has developed into a critical focus in healthcare delivery and nursing. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated the importance of PCC as patients, families, and healthcare providers encountered many situations where it was difficult to meet patient needs in a manner that provided support and recognized PPC needs due to isolation, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), need to wear masks, and separation from families and significant others during times of illness, critical illness, and death. The care provided to patients with COVID-19 has been complex, and these patients, due to concern about exposing family members, were not able to have family visits-this added to the need for nurses to demonstrate caring, focusing on patients and assisting patients in making decisions about their health care with respect from healthcare professionals during the care process. Caring is also important in public and community health, which was critical during the pandemic as healthcare providers communicated with the public about actions that were needed to protect the public.

Caring is the offering of self. This means “offering the intellectual, psychological, spiritual, and physical aspects one possesses as a human being to attain a goal. In nursing, this goal is to facilitate and enhance patients' ability to do and decide for themselves” and recognizes that competent caring considers the following aspects (Scotto, 2003, pp. 290-291):

- The intellectual aspect consists of an acquired, specialized body of knowledge, analytical thought, and clinical judgment, which are used to meet human health needs.

- The psychological aspect includes the feelings, emotions, and memories that are part of the human experience.

- The spiritual aspect, as for all human beings, seeks to answer the question, why? What is the meaning of this?

- The physical aspect is the most obvious. Nurses go to patients' homes, the bedside, and a variety of clinical settings where they apply their strengths, abilities, and skills to attain a goal. For this task, nurses must consider care for themselves so that they are able to meet work requirements, and then they must be accomplished and skillful in nursing interventions.

As noted above, for nurses and nursing students to care for others, they need to also care for themselves, as discussed in Chapter 4, “Success in Your Nursing Education.” It takes energy to care for another person, and this effort is draining. Developing positive, healthy behaviors and attitudes can protect a nurse later when more energy is required in the practice of nursing and have an impact on performance and, thus, on quality care outcomes, as discussed in other chapters in this text.

As students continue through their nursing education program, the issue of the difference between medicine and nursing often arises. Some nurses say that caring is only done by nurses, but is this accurate? Nurses are not the only healthcare professionals-for example, physicians may say they have a caring attitude, and caring is part of their profession, and others, such as social workers, psychologists, pharmacists, and so on. However, what has happened with nursing (which may not have been so helpful) is that when caring and nursing are discussed, they may be described only in emotional terms (Moland, 2006). This view ignores the fact that caring involves competent assessment of the patient to determine what needs to be done and the ability to subsequently provide that care. For both endeavors to be effective, the healthcare provider must have knowledge. The typical description used for medicine is “curing”; for nursing, it is “caring.” This type of extreme dichotomy is not helpful for either the nursing or medical professions individually and has implications for the interrelationship between the two professions, adding conflict and creating difficulty in communication and coordination in the interprofessional team.

The use of technology in health care has increased steadily since 1960, particularly since the end of the 20th century. Nurses work with technology daily, and more and more care involves some type of technology. This has a positive impact on care; however, there have been questions about the possible negative impact of technology on caring. Does technology create a barrier between the patient and the nurse that interferes with the nurse-to-patient relationship? Because of this concern, there must be an effort to effectively combine technology and caring because both are critical to positive patient outcomes. In nursing, this synergistic relationship is referred to as “technological competency as caring” (Locsin, 2016). Nurses who use technology but ignore the patient as a person are just technologists; they are not nurses who use knowledge, caring, critical thinking, clinical reasoning and judgment, and technological skills to recognize the patient as a person. These all need to be recognized as integral parts of the caring process. For example, the nurse who focuses on the computer monitor in the room may get the data needed but does not engage the patient or demonstrate caring in an effective manner-and may miss some important observation data. Later content on technology, particularly digital health, explores this topic more.

Competency

The ANA (2021) standards define competency as “an expected and measurable level of nursing performance that integrates knowledge, skills, abilities, and judgment based on established scientific knowledge and expectations for nursing practice” (p. 86). The goal of competence is to promote quality care. Competency levels change over time as students gain more experience. The report The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health recommends that all nurses engage in lifelong learning as competency requires ongoing assessment and development throughout a nurse's career (IOM, 2011). Nurses in practice need to demonstrate certain competencies to continue to practice. Meeting staff development/educational requirements assists in improving staff practice at the level expected, but it does not ensure it. Students, however, must satisfy competency requirements to progress through the nursing program and graduate. Competencies incorporated in nursing education standards include elements of knowledge, caring, and technical skills and affect curricula, as discussed in other chapters in this text. The competencies also note in Domain 1 the importance of knowledge for nursing practice (AACN, 2023).

After a number of reports described serious problems with health care, including errors and poor-quality care, an initiative was developed to identify core competencies for all healthcare professions, including nursing, to build a bridge across the quality chasm to improve care (IOM, 2003). It was hoped that these competencies would have an impact on education for and practice in health professions. The core competencies are identified here and discussed throughout this text (p. 4).

- Provide patient-centered care: Identify, respect, and care about patients' differences, values, preferences, and expressed needs; relieve pain and suffering; coordinate continuous care; listen to, clearly inform, communicate with, and educate patients; share decision-making and management; and continuously advocate for disease prevention, wellness, and promotion of healthy lifestyles, including a focus on population health. The description of this core competency relates to content found in definitions of nursing, nursing standards, nursing social policy statements (Fowler, 2015), and nursing theories.

- Work in interdisciplinary [interprofessional] teams: Cooperate, collaborate, communicate, and integrate care in teams to ensure that care is continuous and reliable. There is much knowledge available about teams and how they impact care. Leadership is a critical component of working on teams-both as a team leader and as a follower or member. Many of the major nursing roles that are discussed in this chapter require working with teams.

- Employ evidence-based practice: Integrate the best research with clinical expertise and patient values for optimal care and participate in learning and research activities to the extent feasible. In this chapter, EBP has been mentioned about knowledge and caring as they relate to research.

- Apply quality improvement: Identify errors and hazards in care; understand and implement basic safety design principles, such as standardization and simplification; continually understand and measure the quality of care in terms of structure, process, and outcomes in relation to patient and community needs; and design and test interventions to change processes and systems of care, with the objective of improving quality. Understanding how care is provided and which problems in providing care arise often leads to the need for additional knowledge development through research.

- Utilize informatics: Communicate, manage knowledge, mitigate error, and support decision-making using information technology. This chapter focuses on knowledge and caring, both of which require the use of informatics to meet patient needs.

Following the identification of these core competencies, nursing adapted them so that there would be nursing-focused core competencies; however, this does not exclude the importance of the nursing profession applying the healthcare profession core competencies. The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) competencies are (2020):

- Patient/person-centered care

- Teamwork and collaboration

- Evidence-based practice

- Quality improvement

- Safety

- Informatics

In comparing the two sets of competencies, QSEN separates quality and safety and, thus, identifies six competencies instead of five. The content is similar.

| Stop and Consider 2 |

|---|

| Critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and judgment are related but not the same. |

Nursing Scholarship

There is a great need to search for better solutions and knowledge and then disseminate knowledge in health care. This discussion about scholarship in nursing explores the meaning of scholarship, the meaning and impact of theory and research, use of professional literature, and new scholarship modalities.

What Does Scholarship Mean?

The AACN defines scholarship in nursing as “the generation, synthesis, translation, application, and dissemination of knowledge that aims to improve health and transform health care” (2018, p. 3). When asked which activities might be considered scholarship, the common response is “research.” However, when Boyer, who was one of the early experts focused on scholarship, questioned this view of scholarship, he suggested that other activities may also be scholarly (1997):

- Discovery: New and unique knowledge is generated (research, theory development, philosophical inquiry).

- Teaching: The teacher creatively builds bridges between his or her own understanding and the students' learning.

- Application: The emphasis is on the use of new knowledge in solving society's problems (practice).

- Integration: Relationships among disciplines are discovered (publishing, presentations, grant awards, licenses, patents, or products for sale; must involve two or more disciplines, thus advancing knowledge over a broader range).

These four aspects of scholarship are critical components of academic nursing and support the values of a profession committed to both social relevance and scientific advancement.

Scholarship applies in both the educational, research, and practice arenas and emphasizes that nursing is a PCC practice profession (AACN, 2018). Nursing theory and research are described in this chapter and included in other chapters. All nurses should demonstrate scholarship and leadership, and it is important that nurses understand what this means and how it affects practice.

Nursing has a long history of scholarship, although some periods seem to have been more active than others in terms of major contributions to nursing scholarship. Exhibit 2-1 describes some of the milestones that are important in understanding nursing scholarship as the profession developed first in Britain and then in the United States.

| Exhibit 2-1 A Brief History of Selected Nursing Scholarship Milestones | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nursing Theory

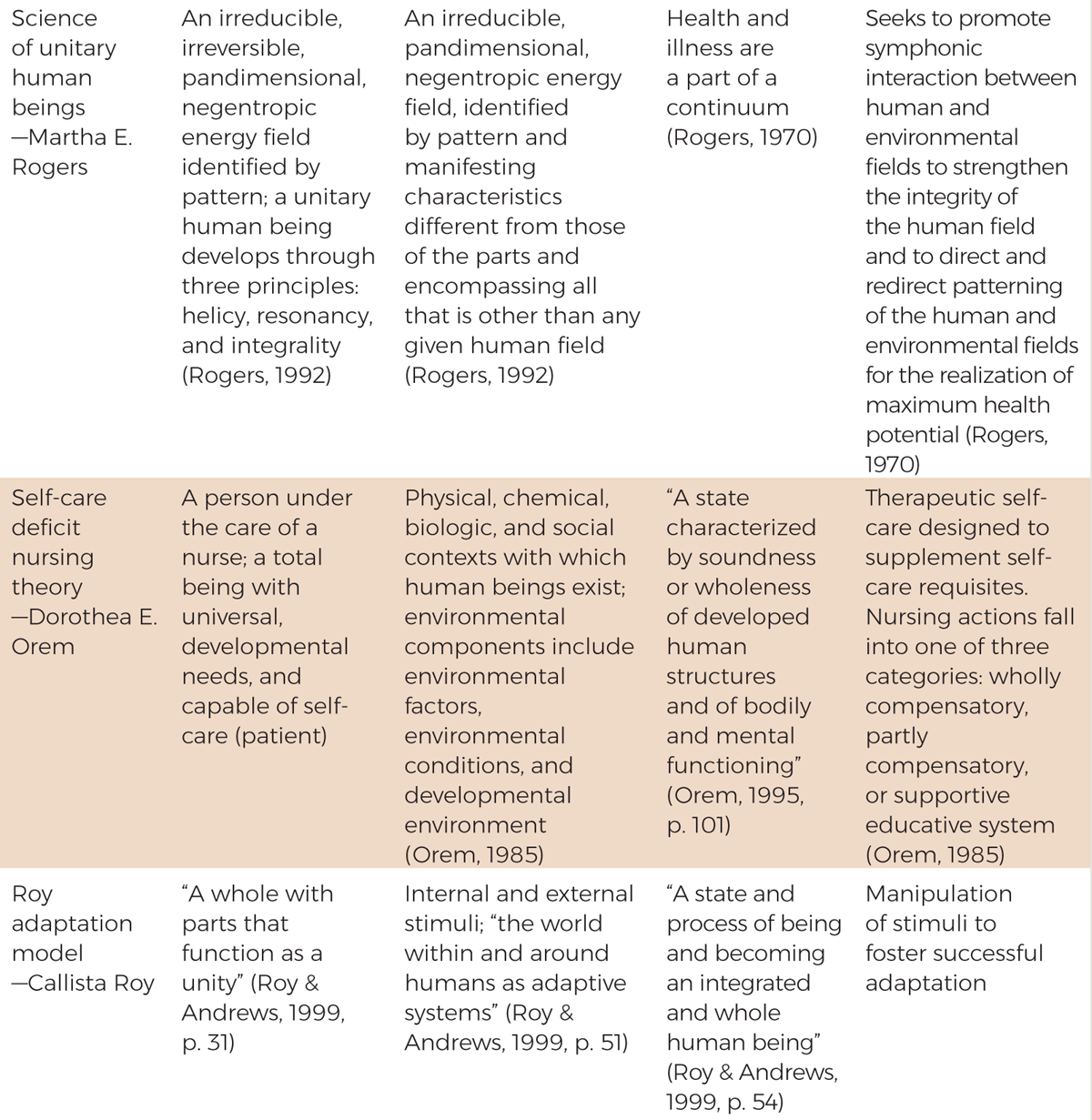

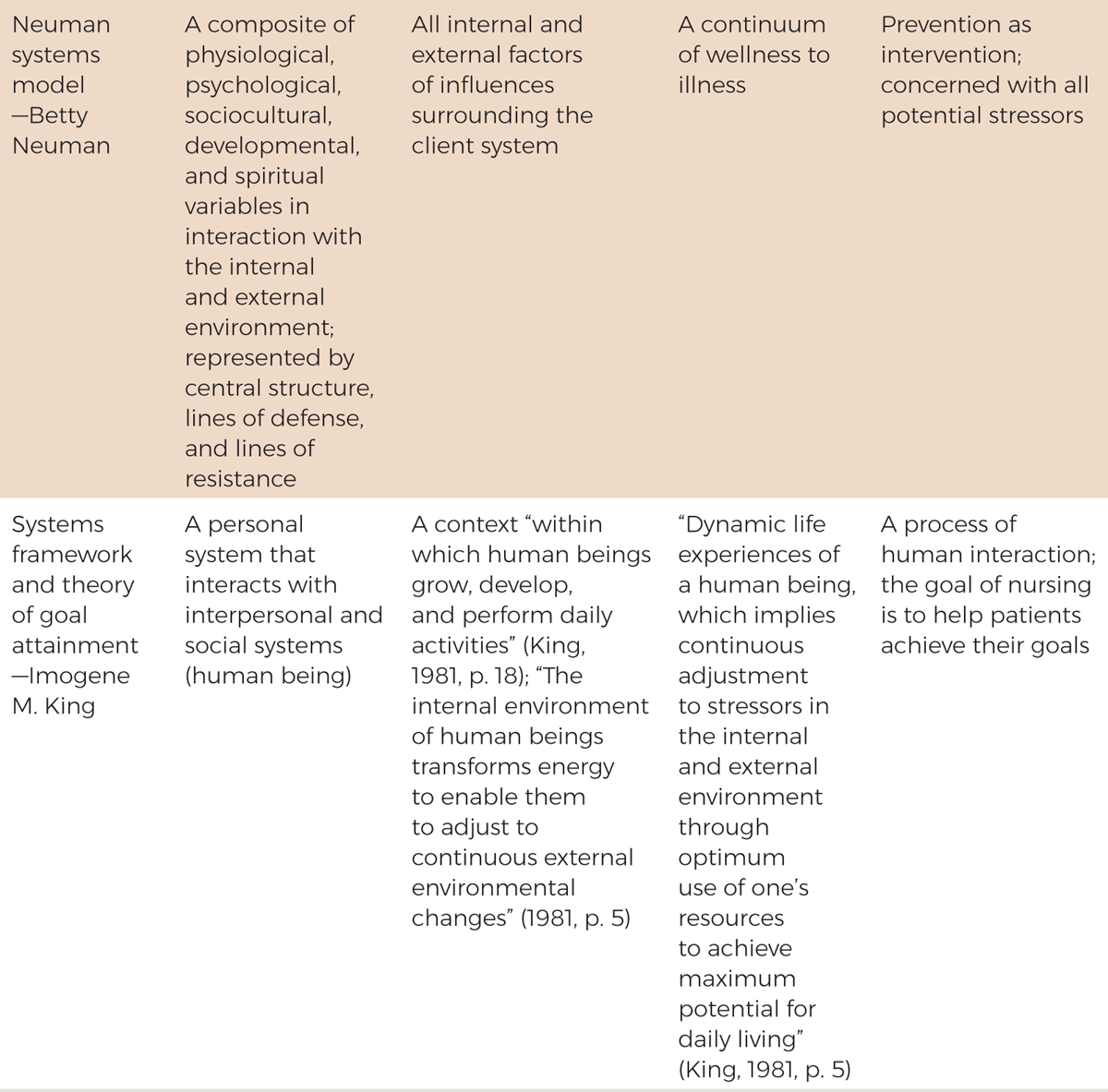

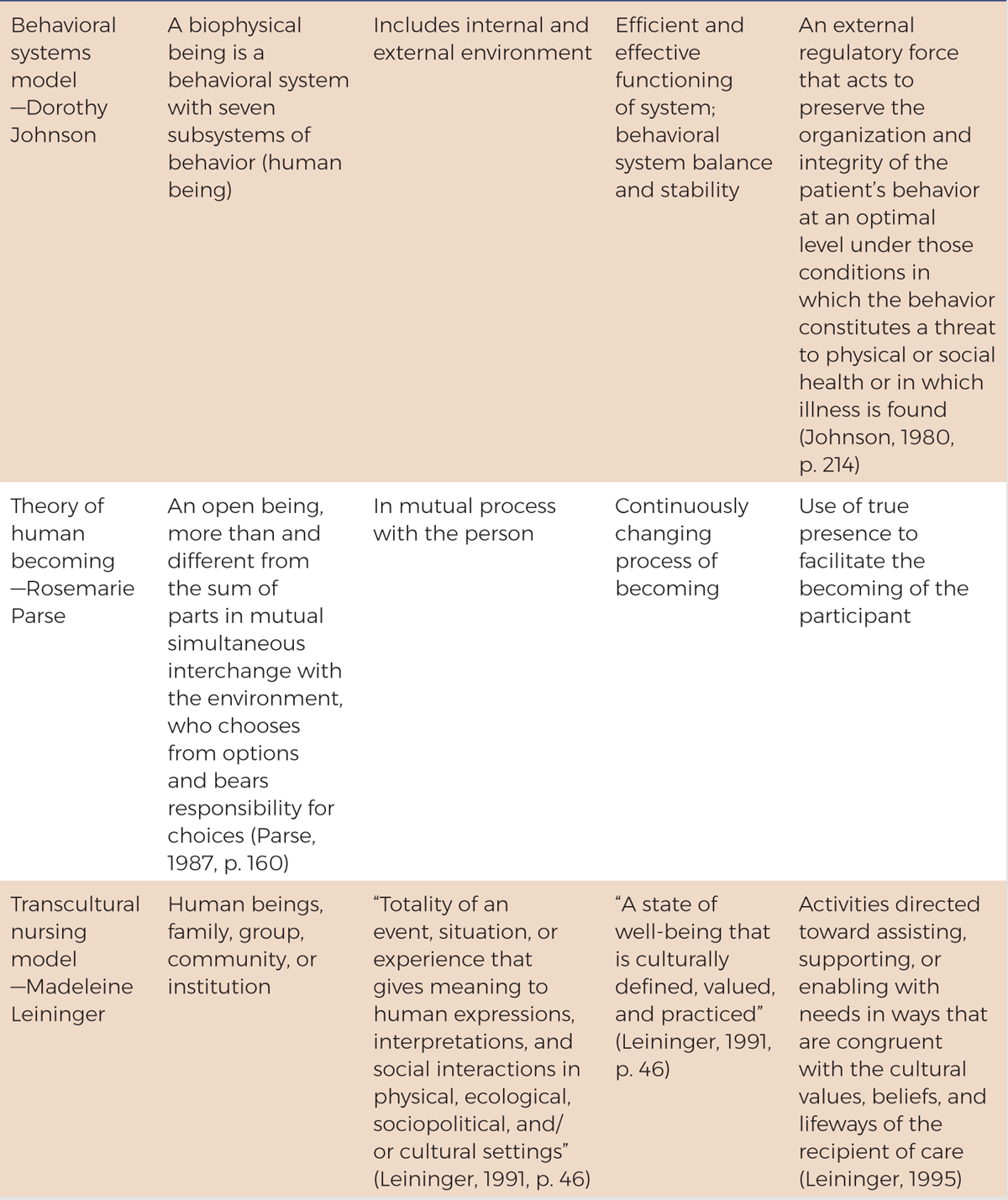

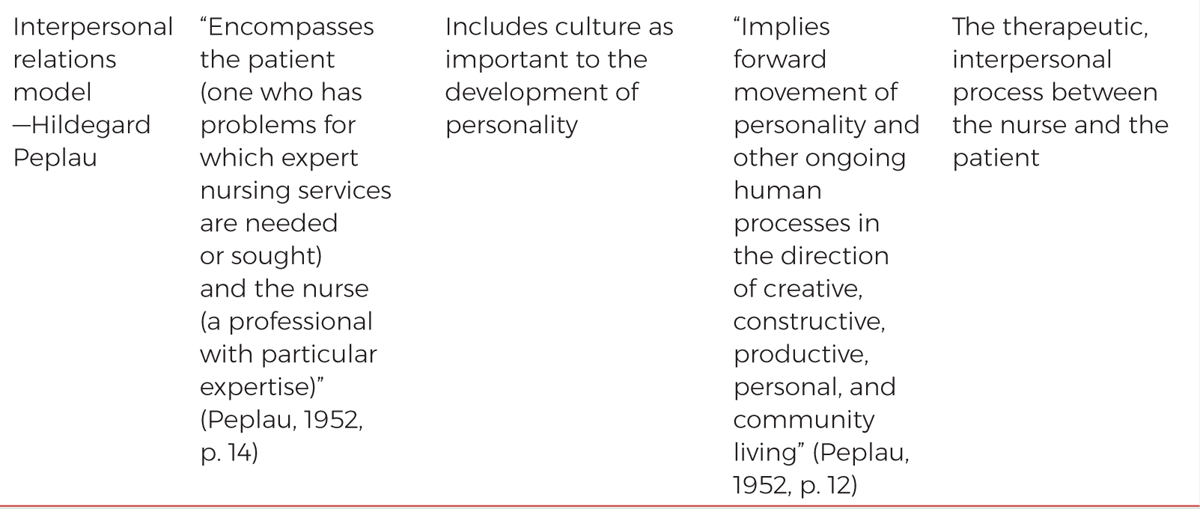

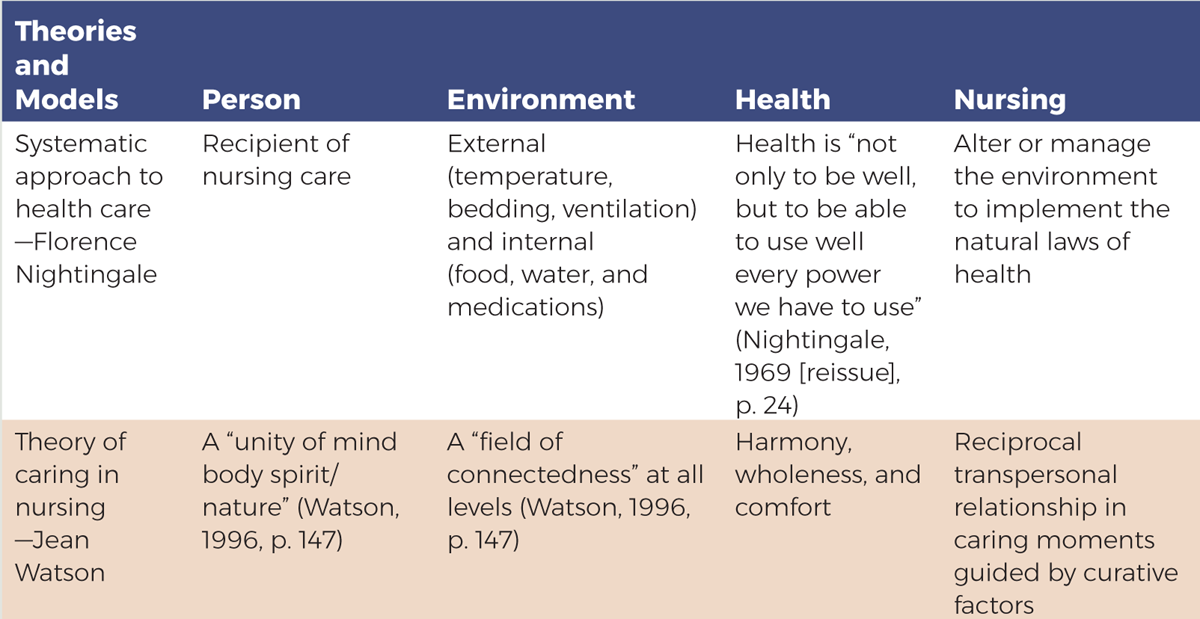

A simple description of a theory is “words or phrases (concepts) joined together in sentences, with an overall theme, to explain, describe, or predict something” (Sullivan, 2006, p. 160). Theories help nurses understand and find meaning in nursing. Many nursing theories have been developed since Nightingale's contributions to nursing, particularly during the 1960s through 1980s. These theories vary widely in their scope and approach. This surge in development of nursing theories was related to the need to “justify nursing as an academic discipline” and “the need to develop and describe nursing knowledge” (Maas, 2006, p. 7). Some of the major theories are described in Exhibit 2-2 from the perspective of how each description, beginning with Nightingale, considers the concepts of the person, the environment, health, and nursing.

| Exhibit 2-2 Overview of Major Nursing Theories and Models |

|---|

A box is titled Overview of Major Nursing Theories and Models.

A box is titled Overview of Major Nursing Theories and Models, continued.

A box is titled Overview of Major Nursing Theories and Models, continued.

A box is titled Overview of Major Nursing Theories and Models, continued.

A box is titled Overview of Major Nursing Theories and Models, continued. The box is in the form of a table. The table consists of five columns: Theories and Models, Person, Environment, Health, and Nursing. The row entries are as follows. Row 1. Theories and Models: Systematic approach to health care, Florence Nightingale. Person: Recipient of nursing care. Environment: External, temperature, bedding, ventilation, and internal, food, water, and medications. Health: Health is not only to be well, but to be able to use well every power we have to use, Nightingale, 1969, reissue, page 24. Nursing: Alter or manage the environment to implement the natural laws of health. Row 2. Theories and Models: Theory of caring in nursing, Jean Watson. Person: A unity of mind body spirit or nature, Watson, 1996, p. 147. Environment: A field of connectedness, at all levels, Watson, 1996, p. 147. Health: Harmony, wholeness, and comfort. Nursing: Reciprocal transpersonal relationship in caring moments guided by curative factors. The box is in the form of a table. The table consists of five columns: Theories and Models, Person, Environment, Health, and Nursing. The row entries are as follows. Row 3. Theories and Models: Science of unitary human beings, Martha E. Rogers. Person: An irreducible, irreversible, pandimensional, negentropic energy field identified by pattern; a unitary human being develops through three principles: helicy, resonancy, and integrality, Rogers, 1992. Environment: An irreducible, pandimensional, negentropic energy field, identified by pattern and manifesting characteristics different from those of the parts and encompassing all that is other than any given human field, Rogers, 1992. Health: Health and illness are a part of a continuum, Rogers, 1970. Nursing: Seeks to promote symphonic interaction between human and environmental fields to strengthen the integrity of the human field and to direct and redirect patterning of the human and environmental fields for the realization of maximum health potential, Rogers, 1970. Row 4. Theories and Models: Self-care deficit nursing theory, Dorothea E. Orem. Person: A person under the care of a nurse; a total being with universal, developmental needs, and capable of self-care, patient, Orem, 1985. Environment: Physical, chemical, biologic, and social contexts within which human beings exist; environmental components include environmental factors, environmental conditions, and developmental environment, Orem, 1985. Health: A state characterized by soundness or wholeness of developed human structures and of bodily and mental functioning, Orem, 1995, p.101. Nursing: Therapeutic self-care designed to supplement self-care requisites. Nursing actions fall into one of three categories: wholly compensatory, partly compensatory, or supportive educative system, Orem, 1985. Row 5. Theories and Models: Roy adaptation model, Callista Roy. Person: A whole with parts that function as a unity, Roy and Andrews, 1999, p. 31. Environment: Internal and external stimuli; 'the world within and around humans as adaptive systems, Roy and Andrews, 1999, p. 51. Health: 'A state and process of being and becoming an integrated and whole human being, Roy and Andrews, 1995. Nursing: Manipulation of stimuli to foster successful adaptation. A continuation of the previous page reads as follows. The table consists of five columns: Theories and Models, Person, Environment, Health, and Nursing. The row entries are as follows. Row 6. Theories and Models: Neuman systems model, Betty Neuman. Person: A composite of physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, and spiritual variables in interaction with the internal and external environment; represented by central structure, lines of defense, and lines of resistance. Environment: All internal and external factors of influences surrounding the client system. Health: A continuum of wellness to illness. Nursing: Prevention as intervention; concerned with all potential stressors. Row 7. Theories and Models: Systems framework and theory of goal attainment, Imogene M. King. Person: A personal system that interacts with interpersonal and social systems, human being. Environment: A context 'within which human beings grow, develop, and perform daily activities, King, 1981, p. 18; The internal environment of human beings transforms energy to enable them to adjust to continuous external environmental changes, 1981, p. 5. Health: Dynamic life experiences of a human being, which implies continuous adjustment to stressors in the internal and external environment through optimum use of one's resources to achieve maximum potential for daily living, King, 1981, p. 5. Nursing: A process of human interaction; the goal of nursing is to help patients achieve their goals. A continuation of the previous page reads as follows. The box is in the form of a table. The table consists of five columns: Theories and Models, Person, Environment, Health, and Nursing. The row entries are as follows. Row 8. Theories and Models: Behavioral systems model, Dorothy Johnson. Person: A biophysical being is a behavioral system with seven subsystems of behavior, human being. Environment: Includes internal and external environment. Health: Efficient and effective functioning of system; behavioral system balance and stability. Nursing: An external regulatory force that acts to preserve the organization and integrity of the patient's behavior at an optimal level under those conditions in which the behavior constitutes a threat to physical or social health or in which illness is found. Row 9. Theories and Models: Theory of human becoming, Rosemarie Parse. Person: An open being, more than and different from the sum of parts in mutual simultaneous interchange with the environment, who chooses from options and bears responsibility for choices. Environment: In mutual process with the person. Health: Continuously changing process of becoming. Nursing: Use of true presence to facilitate the becoming of the participant. Row 10. Theories and Models: Transcultural nursing model, Madeleine Leininger. Person: Human beings, family, group, community, or institution. Environment: Totality of an event, situation, or experience that gives meaning to human expressions, interpretations, and social interactions in physical, ecological, sociopolitical, and forward slash or cultural settings. Health: A state of well-being that is culturally defined, valued, and practiced. Nursing: Activities directed toward assisting, supporting, or enabling with needs in ways that are congruent with the cultural values, beliefs, and lifeways of the recipient of care. A continuation of the previous page reads as follows. The box is in the form of a table. The table consists of five columns: Theories and Models, Person, Environment, Health, and Nursing. The row entries are as follows. Row 11. Theories and Models: Interpersonal relations model, Hildegard Peplau. Person: Encompasses the patient, one who has problems for which expert nursing services are needed or sought, and the nurse, a professional with particular expertise. Environment: Includes culture as important to the development of personality. Health: Implies forward movement of personality and other ongoing human processes in the direction of creative, constructive, productive, personal, and community living. Nursing: The therapeutic, interpersonal process between the nurse and the patient. Source line reads, Data from Johnson, D. 1980. The behavioral systems model for nursing. In J. Riehl and C. Roy, Editors, Conceptual models for nursing practice, Second Edition, p p. 207 to 216. Appleton-Century-Crofts; King, I. M. 1981. A theory of nursing: Systems, concepts, process. Wiley; Leininger, M. M. 1991. Culture care diversity and universality: A theory of nursing. National League for Nursing; Leininger, M. M. 1995. Transcultural nursing perspectives: Basic concepts, principles, and culture care incidents. In M. M. Leininger, Editor, Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, research, and practices, Second Edition, p p. 57 to 92. McGraw-Hill; Nightingale, F, 1969, reissue. Notes on nursing: What it is and what it is not. Dover; Orem, D. 1985. Nursing: Concepts of practice, Third Edition. Mosby; Orem, D. 1995. Nursing: Concepts of practice, Fifth Edition. Mosby; Parse, R. R. 1987. Nursing science: Major paradigms, theories, and critiques. Saunders; Peplau, H. 1952. Interpersonal relations in nursing. G. P. Putnam's Sons; Rogers, M. E. 1970. An introduction to the theoretical basis of nursing. Davis; Rogers, M. E. 1992. Nursing science and the space age. Nursing Science Quarterly, 5, 27 to 34; Roy, C, and Andrews, H. A. 1999. The Roy adaptation model. Appleton and Lange; Watson, J. 1996. Watson's philosophy and theory of human caring in nursing. In J. P. Riehl-Sisca, Editors, Conceptual models for nursing practice, p p. 219 to 235. Appleton and Lange, as cited in Masters, K. 2023. Role development in professional nursing practice. Jones and Bartlett Learning. Data from Johnson, D. (1980). The behavioral systems model for nursing. In J. Riehl & C. Roy (Eds.), Conceptual models for nursing practice (2nd ed., pp. 207-216). Appleton-Century-Crofts; King, I. M. (1981). A theory of nursing: Systems, concepts, process. Wiley; Leininger, M. M. (1991). Culture care diversity and universality: A theory of nursing. National League for Nursing; Leininger, M. M. (1995). Transcultural nursing perspectives: Basic concepts, principles, and culture care incidents. In M. M. Leininger (Ed.), Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, research, and practices (2nd ed., pp. 57-92). McGraw-Hill; Nightingale, F. (1969 [reissue]). Notes on nursing: What it is and what it is not. Dover; Orem, D. (1985). Nursing: Concepts of practice (3rd ed.). Mosby; Orem, D. (1995). Nursing: Concepts of practice (5th ed.). Mosby; Parse, R. R. (1987). Nursing science: Major paradigms, theories, and critiques. Saunders; Peplau, H. (1952). Interpersonal relations in nursing. G. P. Putnam's Sons; Rogers, M. E. (1970). An introduction to the theoretical basis of nursing. Davis; Rogers, M. E. (1992). Nursing science and the space age. Nursing Science Quarterly, 5, 27-34; Roy, C., & Andrews, H. A. (1999). The Roy adaptation model. Appleton & Lange; Watson, J. (1996). Watson's philosophy and theory of human caring in nursing. In J. P. Riehl-Sisca (Ed.), Conceptual models for nursing practice (pp. 219-235). Appleton & Lange, as cited in Masters, K. (2023). Role development in professional nursing practice. Jones & Bartlett Learning. |

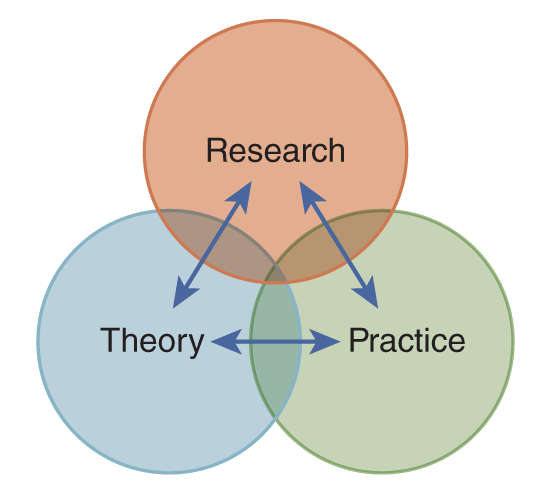

Since the late 1990s and the development of much of the content described in Exhibit 2-2, illustrating how theories developed, nursing education has placed less emphasis on nursing theory. This change has been controversial. Theories may be used to provide frameworks for research studies and to test theory applicability. In addition, practice may be guided by nursing theories. In hospitals and other healthcare organizations, the nursing department may identify a specific theory or a model on which the staff bases its mission and practice. In these organizations, it is usually easy to see how the designated theory is present in the official documents about the department, but it is not always so easy to see how the theory impacts the day-to-day practice of nurses in the organization. It is important to remember that theories do not tell nurses what they must do or how they must do something; rather, they are guides-abstract guides. Figure 2-1 describes the relationship among theory, research, and practice.

Figure 2-1 Relationship theory, research, practice.

A Venn diagram illustrates the relationships between Research, Theory, and Practice.

The Venn diagram consists of three overlapping circles, each labeled as follows: one for Research, another for Theory, and the third for Practice. Arrows flow between these labels, indicating ongoing interactions and influences among research, theory, and practice, forming a cyclical relationship.

Reproduced from Masters, K. (2023). Role development in professional nursing practice. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

As noted, most of the existing nursing theories were developed from the 1970s through the 1990s. Now, we might ask what issues future theories will address. In 1992, the following were predicted as possible focus areas for the development of future nursing theories (Meleis, 1992, pp. 112-114):

- Human science underlying the discipline that is predicated on understanding the meanings of daily-lived experiences as they are perceived by the members or the participants of the science

- Increased emphasis on practice orientation, or actual, rather than “ought-to-be” practice

- Mission of nursing to develop theories to empower nurses, the discipline, and clients (patients)

- Acceptance of the fact that women may have different strategies and approaches to knowledge development than men

- Nursing's attempt to understand consumers' experiences for the purpose of empowering them to receive optimum care and maintain optimum health

- Efforts to broaden nursing's perspective, which includes efforts to understand the practice of nursing in third-world countries

These potential focus areas for theories are somewhat different from those evidenced in past theories and are important today in providing a framework for practice. Consumerism is highlighted through a better understanding of consumers/patients and empowering them. Empowering nurses is also emphasized. The suggestion that female nurses and male nurses might approach care issues differently has not really been addressed in the past. The effort to broaden nursing's perspective is highly relevant today, given the increase in globalization and the emphasis on culturally appropriate care. Developed and developing countries can share information via the internet in a matter of seconds. There are fewer boundaries than ever before, such that better communication and information exchange have become possible. This has been experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing a global need to support healthcare delivery and share information. A need for nursing to expand its geographic scope certainly exists because, globally, nursing issues and care problems are often the same or very similar. Efforts to solve these problems on a worldwide scale are necessary. Take, for example, issues such as infectious diseases: Because of the ease of travel, they can quickly spread from one part of the world to another in which the disease is relatively unknown. How we understand nursing and the knowledge required to improve performance are critical aspects that may be assisted by greater sharing of experiences globally. In conclusion, theory development is not as active today as it was in the past-it is not clear what role nursing theories might have and how theories might change in the future, but they have had an impact on the profession and on practice.

Nursing Research

Nursing research is “systematic inquiry that uses disciplined methods to answer questions and solve problems” (Polit & Beck, 2021, p. 4). The major purpose of research is to expand nursing knowledge to improve patient care and outcomes. Research helps to explain and predict the care that nurses provide. Two major types of research exist: basic and applied. Basic research is conducted to gain knowledge for knowledge's sake, and basic research results may then be used in applied or clinical research.

Connecting research with practice has improved both in nursing education and practice. There is a need for better collaboration between nurses in practice and the research process. Nursing care-all health care-needs to be patient/person-centered and evidence-based (IOM, 2003), and research should also consider PCC. This does not mean that there is no need for research in administration/management and in education because there are critical needs in these areas; rather, it means that nursing needs to gain more knowledge about the nursing process with patients at the center. Because of these issues, EBP has become more central in nursing practice, as discussed in the chapter “Employ Evidence-Based Practice.” The research process is similar to the nursing process: identify a problem using data, determine goals, describe what will be done, and then assess results.

Professional Literature

Professional literature is an important part of nursing scholarship, but it is important to remember that health care, including nursing, undergoes frequent changes as new information becomes available and more research offers new perspectives (Zerwekh & Garneau, 2020). Professional literature is found in textbooks and in professional journals, and now there is even more access through the internet. This literature represents a repository of nursing knowledge that is accessible to nursing students and nurses. It is important that nurses keep up with professional literature, including research in their specialty areas, given the increased emphasis on EBP. Increased access to journals is a positive change because it makes knowledge more accessible when it is needed along with many other information resources now accessible through the internet, for example, government resources from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It is also important for nurses to view publishing as a professional responsibility as they progress in their careers.

Textbooks typically are a few years behind current information because of the length of the publication schedule. Although this gap is improving, it still takes significantly longer to write and publish a textbook than a journal and its articles. It is also more expensive to publish a textbook, so new editions do not come out annually or, as in the case of many journals, monthly. The content found in textbooks provides background information and details on particular topics. A textbook is peer reviewed when content is shared with experts on the topic for feedback to the author(s). Today, many textbook publishers offer companion websites to provide additional material and, in some cases, more updated content or references. More publishers are publishing textbooks in e-book format; some offer both hard copy and e-books, and others offer only e-books. This change may reduce the delay in getting textbooks published and provide a method for updating content quickly.

Content in journals is typically more current than in textbooks and usually focuses on a very specific topic in less depth than a textbook. Higher quality journals are peer reviewed. This means that several nurses who have expertise in the manuscript's topic review submitted manuscripts. A consensus is then reached with the editor regarding whether to publish the manuscript. Online access to journal articles has made this literature more accessible to nurses. A newer option for publishing in journals today is open-access journals, which offer unrestricted access and unrestricted reuse (for example, no copyright fee or permission is required if one uses content from some open-access journals). These journals are usually available free online to anyone who wants access. Publishing in these journals can vary; for example, some use peer review, and some do not. Authors must pay fees to publish in the journal, and, sometimes, these fees are high. Authors may choose nonopen-access journals with more prestige if they can get their manuscripts accepted. This is still a relatively new area and, thus, it is unknown how this will develop in the future-but the internet encourages free use of information. This has had an impact on how we get professional information and on the many barriers set up in the past that may limit publishing and sharing information.

Nursing professional organizations often publish journals. The focus of articles on research studies published in scientific nursing journals has changed; for example, there is less emphasis on theory-based studies and more on clinical problems. Any nurse with expertise in an area can submit an article for publication; however, this does not mean all manuscripts are published. The profession needs more nurses publishing, particularly in journals. Publications are listed on nurses' résumés or curricula vitae as scholarly endeavors and have an impact on career goals and promotion. Exhibit 2-3 identifies examples of nursing journals.

| Exhibit 2-3 Examples of Nursing Journals |

|---|

|

New Modalities of Scholarship

Scholarship includes publications, copyrights, licenses, patents, or products for sale. Nursing is expanding into several new modalities that can be considered scholarship. Many of these modalities relate to web-based learning-including course development and learning activities and products, such as case software for simulation experiences-and involve other technology and devices, such as tablets and smartphones. Most of these new modalities relate to teaching and learning in academic programs, although many have expanded into staff education and continuing education. In developing these modalities, nurses are creating innovative methods, developing programs and learning outcomes, improving professional development, applying technical skills, and sharing scholarship in a timelier manner with the goal of improving nursing practice. Interprofessional approaches are also used more today, and this improves integrative scholarship-something nurses need to be aware of and engage in as improvements are made.

| Stop and Consider 3 |

|---|

| Because scholarship is a critical aspect of professionalism, professional nurses need to demonstrate scholarship. |

Multiple Nursing Roles and Leadership

Nurses use knowledge and caring as they provide care to patients; however, there are other important aspects of nursing. As nurses apply knowledge and caring, they function in multiple roles.

Key Nursing Roles

Before discussing nursing roles, it is important to discuss some terminology related to roles. A role can vary depending on the context. Role means the expected and actual behaviors that one would associate with a position, such as a nurse, physician, teacher, pharmacist, and so on. Connected to role is status, which is a position in a social structure, with rights and obligations-for example, a nurse manager would have more status in an HCO compared with a staff nurse. As a person assumes a new role, the person experiences role transition. Nursing students are in role transition as they gradually learn about nursing roles. All nursing roles are important in patient care, and typically, these roles are interconnected in practice. Students learn about the roles and what is necessary to be competent to meet role expectations. Professional identity is important as students progress through their nursing education program and during their early years of practice. It is defined as “a sense of oneself, and in relationship with others, that is influenced by characteristics, norms, and values of the nursing discipline, resulting in an individual thinking, acting, and feeling like a nurse” (Godfrey & Young, 2021, p. 264). “Fostering professional identity in nursing education, practice, and regulation is an example of an evidence-based intervention that may transform workplaces into environments that support nurse well-being; prevent burnout, fatigue, mental and physical stress, moral distress, and moral injury; and promote work satisfaction and retention” (Owens & Godfrey, 2022). The four areas of concern in professional identity are values and ethics, knowledge, nursing leadership, and professional behavior, as viewed through words, actions, and presence. As students and then licensed registered nurses develop professional identity, these four concerns are important for success. The ANA Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice notes that a professional identity in nursing “goes a step beyond acting professionally. It focuses on the transformational nature of being a professional rather than on the transactional aspects of professional life, such as clocking-in on time and completing tasks” (ANA, 2021).

Nursing is a complex profession and involves multiple types of consumers of nursing care (for example, individuals, families, specific populations, and communities), multiple types of problems (for example, physical, emotional, sociological, economic, and educational), and multiple settings (for example, hospitals, clinics, communities, schools, the patient's home), and specialties within each of these dimensions. Some roles, such as teaching, administration, and research, do not focus as much on providing direct patient care. Different levels of knowledge, caring, and education may be required for different roles. All of the roles require leadership. The key roles found in nursing are discussed in the following sections. Within a position title, such as a staff nurse, the nurse may have multiple roles, such as provider of care, patient educator, and so on.

Provider of Care: Individual and Teams

The provider of care role is probably what students think nursing is all about-this is the role typically seen in the hospital setting, and the role that most people think of when they think of a nurse. Today, there is a greater emphasis on also understanding and providing care by teams (interprofessional) and on the impact of care delivery. Caring is attached mostly to the provider role, but knowledge is critical to providing quality care. When the nurse is described, it is often caring that is emphasized, with less emphasis on the knowledge and expertise required to provide quality care. This perspective is not indicative of what really happens because nurses need to use knowledge and be competent, as discussed earlier in this chapter. Providing care has moved far beyond the hospital, with nurses providing care in clinics, schools, the community, homes, long-term care, industry, and at many more sites, increasing the need for collaboration, coordination, communication, and teamwork. EBP is interconnected with effective care delivery.

Educator

Nurses spend a lot of time teaching patients, families, communities, and populations. In the educator role, nurses focus on health promotion and prevention and helping the patient (individuals, families, communities, and populations) cope with illness and injury and maintain health. Teaching needs to be planned and based on needs, and nurses must understand and apply teaching principles and methods. Some nurses teach other nurses and healthcare providers in healthcare settings, an activity called “staff education” or “teach” in nursing schools. Nursing education is considered a type of nursing specialty/advanced practice.

Counselor

A nurse may act as a counselor, providing advice and counseling to patients, families, communities, and populations. This is often done in conjunction with other roles.

Manager

In daily practice, nurses act as managers, even if they do not have a formal management position. Management is the process of getting something done efficiently and effectively through and with other people and should be based on evidence-based management (EBM). Nurses might do this by ensuring that a patient's needs are addressed-for example, the nurse might arrange and check that the patient receives needed laboratory work or a rehabilitation session. The nurse who provides patient care needs to plan the care (interventions, timeline, and who will provide specific care), implement the plan, evaluate outcomes, and make changes as needed. Managing care involves critical thinking, clinical reasoning and judgment, planning, decision-making, delegating, collaborating, coordinating, communicating, working with interprofessional teams, and leadership. There are also nurses in formal management positions, such as a manager of a unit, director of nursing or vice president of nursing, dean of a school of nursing, and so on-all are formal managers.

Researcher

Only a small percentage of nurses are actual nurse researchers who design and lead research studies; however, nurses may participate in research in other ways. The most critical means is by using EBP or EBM, which is one of the core healthcare professions and QSEN competencies (QSEN, 2020). Some nurses now hold positions in research studies that may not be nursing research studies. These nurses assist in obtaining informed consent and data collection and may manage research projects.

Collaborator

Every nurse is a collaborator. “Collaboration is a cooperative effort that focuses on a win-win strategy. Each individual needs to recognize the perspective of others who are involved and eventually reach a consensus of common goal(s)” (Finkelman, 2024, p. 318). Nurses collaborate with other healthcare providers, members of the community, government agencies, and many other individuals and organizations. Teamwork is a critical component of daily nursing practice and is discussed in this text.

Change Agent (Intrapreneur)

It is difficult to perform any of the nursing roles without engaging in change. Change is related to patient needs, how care is provided, where care is provided and when, to whom care is provided, and why care is provided. Change is normal in our personal lives today, and the healthcare delivery system is no different as it experiences frequent change. Nurses deal with change wherever they work, but they may also initiate change for care improvement. When a nurse acts as a change agent within the organization where the nurse works, the nurse is an intrapreneur. This requires risk and the ability to see change in a positive light. An example of a nurse acting as a change agent would be a nurse who sees the value in extending visiting hours in the intensive care unit. The nurse reviews the literature on this topic to support EBP interventions; gets feedback from other staff, patients, and families; and then approaches management with a proposal to change visiting hours. The nurse then works with the interprofessional team to plan, implement, and evaluate this change to assess the outcomes.

Entrepreneur

This role is not as common as other roles, though it is found more often today. The entrepreneur works to make changes in a broader sense. Examples include nurses who are healthcare and legal nurse consultants and nurses who establish businesses related to health care, such as a staffing agency, a business to develop a healthcare product, a healthcare media business, or a collaboration with a healthcare technology venture.

Patient Advocate

Nurses serve as advocates on behalf of the patient (individual, groups, populations, communities) and the family. In this role, the nurse acts as a change agent and a risk taker. The nurse speaks for the patient but does not take away the patient's independence. A nurse caring for a patient in the hospital, for example, might advocate with the physician to alter care to allow a dying patient to spend more time with his or her family. A nurse might also advocate for better health coverage by writing to the local congressional representative or by attending a meeting about care in the community-influencing health policy.

Leader

All nursing roles have leadership elements. A leader is a role that nurses assume, either formally by taking an administrative position or informally with others recognizing that someone has leadership characteristics. Leadership is discussed throughout this text.

Summary Points: Roles and What Is Required

To meet the demands of these multiple roles, nurses need to be prepared and competent. Prerequisite courses and the nursing curriculum, through its content, simulation laboratory experiences, and clinical experiences, help students transition to these roles. The prerequisites provide content and experiences related to biological sciences, English and writing (oral and written communication), sociology, government, languages, psychology, mathematics, and statistics. In nursing, course content relates to the care of diverse patients in hospitals, homes, and communities; planning, implementing, and evaluating care; communication and interpersonal relationships; culture; legal and ethical issues; teaching; public/community health; epidemiology; quality improvement; research, EBP, and EBM; health policy; and leadership and management. As discussed earlier in this chapter, this content relates to the required nursing knowledge base.

When students transition to the work setting as registered nurses, they should be competent as beginning nurses; even so, the transition is often difficult. Reality shock may occur. This reaction may occur when a new nurse is confronted with the realities of the healthcare setting and nursing, which are typically very different from what the nurse experienced in school (Kramer, 1985). Knowledge and competency are important, but new nurses also need to develop self-confidence, and they need time to adjust to the differences between the academic world and real-life practice. Some schools of nursing, in collaboration with hospitals, now offer internship/externship and residency programs for new graduates to decrease reality shock, which is discussed in more detail in other chapters. The major nursing roles that you will learn about in your nursing programs are important in practice, but it is also important for you to learn about being an employee, working with and in teams, communicating in real situations, coping with stress at work, and functioning in complex organizations.

More nurses-particularly new graduates-work in hospitals than in other healthcare settings, although the number of nurses working in hospitals is decreasing. Hospital care has changed, with sicker patients staying in the hospital for shorter periods and with greater use of complex technology. These changes have an impact on what is expected of nurses-namely, in terms of competencies.