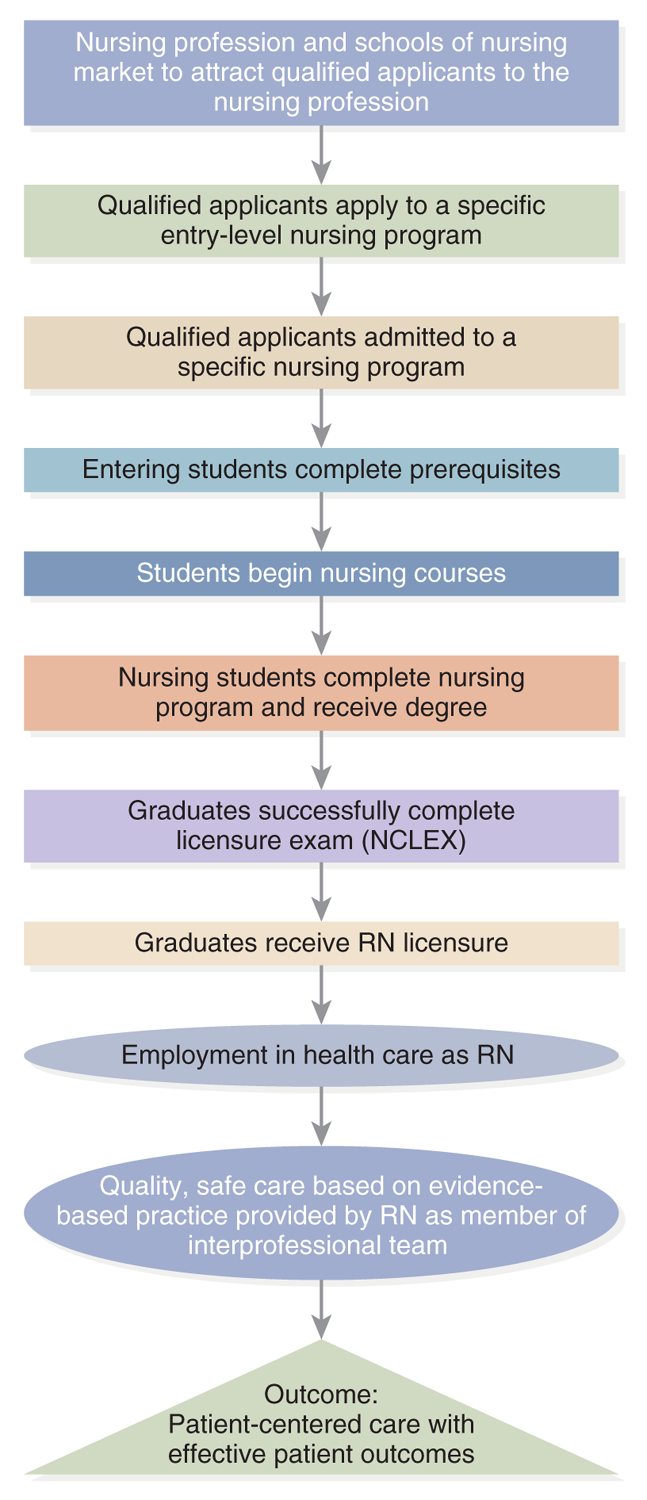

This chapter focuses on three critical concerns in the nursing profession: (1) nursing education, (2) quality of nursing education, and (3) regulatory issues, such as licensure. These concerns are interrelated and change, dependent on each other (for example, graduating from an accredited program is required for licensure), and require regular input from the nursing profession. Even after graduation, nurses should be aware of educational issues, such as appropriate and reasonable accreditation of nursing education programs and ensuring that regulatory issues support the critical needs of the public for quality health care and the needs of the profession. The Tri-Council for Nursing was established in 1977 and now is an alliance of five nursing organizations (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], American Nurses Association [ANA], American Organization for Nursing Leadership [AONL], National Council of State Boards of Nursing [NCSBN], and National League for Nursing [NLN]). In 2010, the Tri-Council issued a consensus policy statement following the U.S. Congress's passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This demonstrates the engagement of the nursing profession in health policy and its collaborative efforts with other healthcare professionals, nursing education, and regulation. This Tri-Council policy statement included the following: “Current healthcare reform initiatives call for a nursing workforce that integrates evidence-based clinical knowledge and research with effective communication and leadership skills. These competencies require increased education at all levels. At this tipping point for the nursing profession, action is needed now to put in place strategies to build a stronger nursing workforce. Without a more educated nursing workforce, the nation's health will be further at risk” (Tri-Council for Nursing, 2010, p. 1). This statement is in line with the Institute of Medicine's (IOM, 2003) recommendations for healthcare profession education. Figure 3-1 highlights the components of the education-to-practice process integrating education, regulation, and practice.

Figure 3-1 From education to practice.

A flowchart depicts the sequential steps from initial application to employment in the nursing profession.

The flowchart depicts the process from aspiring to practicing nurse. It starts with nursing profession and schools of nursing market to attract qualified applicants to the nursing profession, followed by, qualified applicants apply to a specific entry-level nursing program. The subsequent steps are as follows: Qualified applicants admitted to a specific nursing program. Entering students complete prerequisites. Students begin nursing courses. Nursing students complete nursing program and receive degree. Graduates successfully complete licensure exam, N C L E X. Graduates receive R N licensure. Employment in health care as R N. The final step emphasizes Quality, safe care based on evidence-based practice provided by R N as a member of interprofessional team, leading to the outcome of patient-centered care with effective patient outcomes.

Nursing Education

Nursing students may wonder why a nursing text has a chapter that includes content about nursing education. By the time students are reading this text, students have selected a nursing program and enrolled. This content is not included here to help someone decide whether to enter the profession or which nursing program to attend. Rather, it is essential content because education is a critical component of the nursing profession. Nurses need to understand the structure and process of their profession's education, quality issues, and current healthcare and professional issues and trends and should, throughout their careers, be concerned with the profession's education and advocate for improvement and support of students. The following content discusses important elements that impact nursing education.

The education level of entry into practice is an important element. Data from the 2022 National Nursing Workforce Survey, reported in 2023, indicated positive news about the number of registered nurses (RNs) with a baccalaureate degree in nursing (BSN) or higher degree. The percentage of BSN nurses was 71.7% (AACN, 2023a; Smiley, 2022). The Future of Nursing report recommended that the proportion of RNs with baccalaureate degrees should be 80% by 2011; although this goal has not been met, the survey data represent improvement (IOM, 2011). There also has been an increase in Registered Nurse-Bachelor of Science in Nursing (RN-BSN) program enrollment and graduates, which is very positive, supporting the goal. These nurses did not enter nursing with a BSN but pursued it later, even though they are RNs. A critical factor in increasing the number of BSN graduates is increasing enrollment in BSN programs. Data from 2022 indicate that “for the first time since 2000, enrollment in generic baccalaureate programs declined slightly compared to the previous year. When comparing the schools that reported in both 2021 and 2022, enrollment decreased by 3,518 students (1.4%), contrasted with the 2.8% increase between 2020 and 2021. From 2021 to 2022, enrollment decreased in public colleges and private/religious colleges. Private/secular schools and colleges did not see any decline in enrollment. Non-profit institutions had a decline of 7,255 students (3.3%) while for-profit schools had an increase of 3,737 students (10.4%). The North Atlantic, Midwest, and South all experienced a decline in generic baccalaureate enrollment. The greatest declines were seen in the Midwest and North Atlantic regions of the US” (AACN, 2022a; 2023a). Qualified applicants to baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs may be rejected due to numerous factors, such as lack of faculty, clinical sites, classroom space, clinical preceptors, and budget limitations. These factors act as barriers to increasing enrollment and then graduation. These barriers need to be resolved to meet the goals of higher levels of education and completing nursing programs to achieve licensure.

The percentage of minorities enrolling in nursing programs is also an important factor for the profession and health care, and this has increased. Data indicate that there has been improvement in the number of applicants to the various nursing degree programs and in enrollment rates related to student diversity, but much work remains to reach the desired levels to meet the needs of healthcare delivery. For example, an NLN survey reported in 2022 indicated the following: “In the academic year analyzed, nearly 59 percent of students enrolled in basic RN programs are white while 14.6 percent are African American. Hispanic students make up the next largest minority group, at 13 percent, followed by Asian or Pacific Islander at 9 percent and Native Americans at 0.5 percent. By contrast, full-time faculty are racially imbalanced, with more than 76 percent identified as white, while Black nurse educators make up only 4.2 percent of faculty, Hispanics at 11 percent, Asian or Pacific Islander at 4.2 percent, and Native Americans at 0.3 percent. Demographics of sex and gender are similarly skewed. Men make up only 8.1 percent of full-time nurse educators and male nursing students make up just 13.3 percent of RN candidates. Transgender, genderqueer, or gender nonbinary individuals are three-tenths of one percent of full-time faculty and 0.1 percent of enrolled RN students are genderqueer or gender nonbinary” (NLN, 2022a). These demographics impact role models for students, who need to view the profession as diverse. Faculty and student diversity is an ongoing issue in nursing. “Nursing's leaders recognize a strong connection between a culturally diverse nursing workforce and the ability to provide quality, culturally competent patient care. Though nursing has made great strides in recruiting and graduating nurses that mirror the patient population, more must be done before adequate representation becomes a reality. The need to attract students from underrepresented groups in nursing-specifically men and individuals from African American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian, and Alaskan native backgrounds-is a high priority for nursing profession” (AACN, 2023b). This improvement will impact access to care, health equity, and patient outcomes, but it means that nursing education must consider diversity within the school and include content about diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and consider these factors during clinical experiences so that the workforce will be better prepared and understand these critical issues.

It is important to recognize that when reviewing reported data, there is a lag between data collection and analysis, and thus, not to the current year. Though many organizations, such as the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), periodically provide updated data, as does the National League for Nursing (NLN), it is not yet clear the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic might have long-term on student enrollment, completion, and so on. For example, there was a decrease in nursing enrollment in 2020, and some potential applicants were reconsidering graduate-level nursing education due to financial issues and other concerns, such as fear of exposure to COVID-19 and the use of learning technologies and remote learning (Robinson, 2021). Other nursing education issues associated with the experience of COVID-19 noted by Robinson are: Need for the nursing education to keep up with practice, such as in the area of expanding technology use, including digital health; use of different educational methods, such as online courses due to the disruption of nursing education to meet demands of COVID-19, and now greater need for more collaborative and reflective learning environments; preceptor shortage for advanced practice nursing students; difficulties meeting clinical learning experiences for students; need for improved efforts to provide ethical and civil workplaces and assist students in understanding ethical professional practice; and addressing the nursing shortage, which is a global shortage. “Multiple conclusions can be drawn. First, while challenges in nursing education may seem recalcitrant, the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that rapid change is possible. The sustainability of such change is yet to be determined. Second, courageous and ingenious work is being done by leaders in nursing education to chart a bold new future that will include technological innovation, pedagogical reform, foresight thinking, and ethical reform. Finally, what remains constant is the commitment of the academic nursing community to the profession's future by focusing on students' success and well-being” (Robinson, 2021).

A Brief History of Nursing Education

It is impossible to discuss the history of nursing education without reflecting on the history of the profession and the history of health care, as discussed in other chapters-all three are interconnected.

A key historical nursing leader was Florence Nightingale. She changed not only the practice of nursing but also nurses' training, which eventually came to be called “education” rather than “training.” Training focuses on fixed habits and skills; uses repetition, authority, and coercion; and emphasizes dependency, while education focuses more on self-discipline, responsibility, accountability, and self-mastery (Donahue, 1983). Up until the time that Nightingale became involved in nursing, there was little, if any, training for the role. Apprenticeship was used to introduce new recruits to nursing, and often, it was not done effectively. As nursing changed, so did the need for more knowledge and skills, leading to increasingly structured educational experiences. This did not occur without debate and disagreement regarding the best approach. What happened as this was debated, and how does it impact nursing education today?

In 1860, Nightingale established the first school of nursing, St. Thomas, in London, England. She was able to do this because she had received a very good education in the areas of math and science, which was highly unusual for women of her era, and she acknowledged the value of formal education. With her experience in the Crimean War, Nightingale recognized that many soldiers were dying not just because of their wounds but also because of infection and a failure to place them in the best situation for healing. To improve care and apply what she learned during the war, she devoted her energies to upgrading nursing education, with less on-the-job training and more focus on a structured educational program of study, creating a nurse-training school. This training school and those that followed were associated with hospitals and became a source of cheap labor. Students were provided with some formal nursing education, but they also worked long hours in hospitals and were the largest staff source. Over time, this apprenticeship model became more structured and included a more formal educational component. This model was not ideal, although it expanded and improved. During the same era, similar programs opened in the United States. These programs eventually became known as “diploma or hospital schools of nursing.”

Hospitals across the United States began to open schools similar to those in Britain because they realized that students could be used as staff in the hospitals. The quality of these schools varied widely because there were no standards aside from what the individual hospital wanted to do. A few schools recognized early on the need for more content and improved teaching. Over time, some of these schools were creative and formed partnerships with universities so that students could receive some content through an academic institution. Despite these small efforts to improve, the schools continued to be very different from one another, and there were concerns about the lack of standardized quality nursing education.

Major Nursing Reports: Improving Nursing Education

In 1918, an important step was taken through an initiative supported by the Rockefeller Foundation to address the issue of diploma schools of nursing. This initiative culminated in the Goldmark Report (Nursing and Nursing Education in the United States), the first of several major reports about U.S. nursing education. The report included the following key points, which provide a view of some of the common concerns about nursing education in the early 1900s (Goldmark, 1923):

- Hospitals controlled the total educational hours, offering minimal content and, in some cases, no content even when that content was needed.

- Inexperienced instructors with few teaching resources often taught science, theory, and practice of nursing.

- Graduate nurses had limited experience and time to assist the students in their learning and supervise other students.

- Classroom experiences frequently occurred after the students had worked long hours, even during the night.

- Students typically were able to get only the experiences that their hospital provided, with all clinical practice experiences located in one hospital. Consequently, students might not get experiences in specialties, such as obstetrics, pediatrics, and psychiatric-mental health.

The Goldmark Report had an impact, particularly through its key recommendations to (1) separate university schools of nursing from hospitals (this represented only a minority of the schools of nursing); (2) change the control of hospital-based programs to schools of nursing; and (3) require a high school diploma for entry into any school of nursing. These recommendations represented suggestions for major improvements in nursing education. New schools opened based on the Goldmark recommendations, such as schools associated with Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut) and Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, Ohio). It is important to recognize that at this time there was no nursing licensure.

In 1948, the Brown Report was also critical of the quality of nursing education and noted limited improvement since the Goldmark report (Brown, 1948). This led to the implementation of an accreditation program for nursing schools to be conducted by the NLN. Accreditation is a process of reviewing a school's actions and outcomes and reviewing its curriculum based on established standards. The movement toward the university setting and away from hospital-based schools of nursing and the establishment of standards with an accreditation process were major changes for the nursing profession. The ANA and the NLN continue to establish standards for practice and education and support the implementation of nursing standards, for example, the ANA Nursing Scope and Standards of Practice (2021). In addition, the AACN also developed a nursing education accreditation process, which will be discussed later in this chapter. Changes were made, but slowly. The NLN started developing and implementing standards for schools, but it took more than 20 years to accomplish this mission.

A more current report on the assessment of nursing education was published in 2010, Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation (Benner et al., 2010). This report addressed the need to better prepare nurses to practice in a rapidly changing healthcare system to ensure quality care. The conclusions from this qualitative study on nursing education were that there was a need for more improvement and offered the following recommendations. Students should be engaged in the learning process. There needs to be more connection between classroom experience and clinical experience, with a greater emphasis on practice throughout the nursing curriculum. Students should be better prepared to use clinical reasoning and judgment and understand the trajectory of illness. To meet the recommendations of this landmark report, nursing education needed to make major changes and improvements. Exhibit 3-1 describes the report's recommendations, which laid the groundwork for improvement.

| Exhibit 3-1 Recommendations from Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation |

|---|

| Entry and Pathways |

|

| Student Population |

|

| The Student Experience |

|

| Teaching |

|

| Entry to Practice |

|

| National Oversight |

|

A more recent report on the nursing profession, published by the IOM (2011), The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health, delineated several key messages for nurses and also nursing education. Nurses should practice to the fullest extent possible based on their level of education. There should be mechanisms for nurses to easily advance their education, act as full partners in healthcare delivery, and be involved in policy-making, especially as it relates to the healthcare workforce. This report, along with the report by Benner and colleagues (2010), led to a transformation of nursing's role in health care and changes in nursing education to support this practice transformation. In late 2015, a progress report was published to assess the current status of The Future of Nursing recommendations (National Academy of Medicine [NAM], 2015). This report is discussed further in other chapters; however, it is important to note that in this discussion about nursing education, accreditation, and regulation, many of the recommendations require more work, and some have been achieved. The report, The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity (NAM, 2021) notes the following: “The decade ahead will test the nation's nearly 4 million nurses in new and complex ways. Nurses live and work at the intersection of health, education, and communities. Nurses work in a wide array of settings and practice at a range of professional levels. They are often the first and most frequent line of contact with people of all backgrounds and experiences seeking care, and they represent the largest of the health care professions.” This comment and the report have important implications for nursing education.

Entry Into Practice: A Long Debate

The challenges in making changes in the expected education level for entry into practice debate were great when one considers that a very large number of hospitals in communities across the country had diploma schools based on the old model, and these schools were part of and funded by their communities. It was not easy to change these schools or to close them without major nursing and community debate and conflict. These schools constituted the major type of nursing education in the United States through the 1960s. Some schools still exist today, but the number of diploma schools has decreased primarily because of the critical entry into practice debate. The drive to move nursing education into college and university settings was great, but there was also some support to continue with the diploma schools of nursing.

The NLN and the American Nurses Association (ANA, 1965) made strong statements endorsing college-based nursing education as the entry point into the profession. The ANA stated that “minimum preparation for beginning technical (bedside) nursing practice at the present time should be associate degree education in nursing” (p. 107). The situation was very tense. The two largest nursing organizations at the time-one focused primarily on education (NLN) and the other more on practice (ANA)-clearly took a stand. From the 1960s through the 1980s, these organizations tried to alter accreditation, advocated for the closing of diploma programs, and lobbied all levels of government (Leighow, 1996). It was an emotional issue, and even today it continues to be a tense topic because it has not been fully resolved, although stronger statements were made in 2010 to change to a baccalaureate entry level (Benner et al., 2010; IOM, 2011). In summary, since 1965, however, there have been many changes in the educational preparation of nurses:

- The number of diploma schools has gradually decreased, but they still exist.

- The number of associate degree in nursing (ADN) programs has increased. However, there was, and continues to be, concern over the potential development of a two-level nursing system-ADN and BSN-with one viewed as technical and the other as professional. In fact, this did not happen. ADN programs continue to increase, and there has been no change in licensure for any of the nursing programs-graduates of all RN prelicensure programs continue to take the same exam and receive the same license. Many ADN programs now have options to make it easier for students to continue their education and complete BSN requirements.

- BSN programs continue to increase.

- The BSN degree is an admission requirement for graduate nursing programs.

Differentiated Nursing Practice

Another issue related to entry into practice is differentiated nursing practice, which is not a new idea as it has been discussed in nursing literature since the 1990s. It is described as a “philosophy that structures the roles and functions of nurses according to their education, experience, and competence” or “matching the varying needs of clients [patients] with the varying abilities of nursing practitioners” (AONE, 1990, as cited in Hutchins, 1994, p. 52).

How does this work in practice? Does a clinical setting distinguish among RNs who have a diploma, associate degree, BSN degree, or graduate degree? Does this affect role function and responsibilities? Does the healthcare organization (HCO) even acknowledge degrees on name badges? Most HCOs note differences when it comes to RNs with graduate degrees, but many do not necessarily note other degrees, such as the BSN. This approach does not acknowledge that there are differences in the educational programs that award each degree or diploma. The ongoing debate remains difficult to resolve because all RNs, regardless of the type and length of their basic nursing education program, take the same licensing exam. Patients and other healthcare providers rarely understand the differences or even know that differences exist. A difference in salaries due to degrees is the highest level of recognition, and this is done in some healthcare organizations.

In 1995, a joint report was published by the AACN in collaboration with the American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE) (now known as the American Organization for Nursing Leadership [AONL]) and the National Organization for Associate Degree Nursing (NOADN) (now known as the Organization for Associate Degree Nursing [OADN]) (AACN, AONE, & AOADN, 1995). This document described the BSN and the ADN graduate roles (p. 28):

- The BSN graduate is a licensed RN who provides direct care that is based on the nursing process and focused on patients/clients with complex interactions of nursing diagnoses. Patients/clients include individuals, families, groups, populations, and communities in structured and unstructured healthcare settings. The unstructured setting is a geographical or situational environment that may not have established policies, procedures, and protocols and has the potential for variations requiring independent nursing decisions.

- The ADN graduate is a licensed RN who provides direct care that is based on the nursing process and focused on individual patients/clients who have common, well-defined nursing diagnoses. Consideration is given to the patient's/client's relationship within the family. The ADN functions in a structured healthcare setting, which is a geographical or situational environment where the policies, procedures, and protocols for the provision of health care are established. In the structured setting, there is recourse to assistance and support from the full scope of nursing expertise.

Despite increased support, such as from AONL supporting the BSN as the entry-level educational requirement, this question continues to be one of the most challenging issues in the profession and has not been clearly resolved, but it is improving (AACN, 2023l). The AACN believes that “clinicians with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) degree are well-prepared to meet the demands placed on today's nurses. BSN nurses are prized for their skills in critical thinking, leadership, case management, and health promotion and for their ability to practice across a variety of inpatient and outpatient settings. Nurse executives, federal agencies, the military, leading nursing organizations, healthcare foundations, Magnet hospitals, and minority nurse advocacy groups all recognize the unique value that baccalaureate-prepared nurses bring to health care” (AACN, 2023b).

An example of state government interest in this topic occurred in 2017 when the governor of New York signed into state law a requirement that nurses graduating from an associate degree or diploma nursing programs in New York complete a baccalaureate degree in nursing within 10 years of initial licensure. The support for this change was given as follows: “The increasing complexity of the American healthcare system and rapidly expanding technology, the educational preparation of the registered professional nurse must be expanded” (AACN, 2019). Several studies have been conducted addressing this issue. A study by Aiken and colleagues (2003) indicated that there was a “substantial survival advantage” for patients in hospitals with a higher percentage of BSN RNs. Other studies (Estabrooks et al., 2005) supported these patient outcomes. McHugh and Lake (2010) examined how nurses rate their level of expertise as a beginner, competent, proficient, advanced, and expert and how often BSN graduates were selected as preceptors or consulted by other nurses for their clinical judgment. The survey, which was done in 1999 and then the data reused in this 2010 study, included 8,611 nurses. More highly educated nurses rated themselves as having more expertise than less educated nurses, and this correlated with how frequently they were asked to be preceptors or consulted by other nurses. The long-term impact of these types of studies on resolving entry into practice is unknown, but there is more evidence now to support the decision made in 1965, along with recommendations from major reports on nursing (Benner et al., 2010; IOM, 2010).

Aiken and colleagues (2014) continued with more research on these issues and published a study addressing nurse staffing and hospital mortality in nine European countries. This study received major recognition from HCOs and the media. The sample included discharge data for 422,730 patients in nine countries aged 50 years or older who had common surgeries. The survey included 26,516 nurses in the study hospitals. The findings indicated that increasing a nurse's workload by one patient increased the likelihood of a patient dying within 30 days of admission by 7%; in contrast, every 10% increase in the number of nurses with baccalaureate degrees was associated with a 7% decrease in the likelihood of a patient dying within 30 days of admission. These associations imply that patients receiving care in hospitals in which 60% of nurses had baccalaureate degrees and nurses cared for an average of six patients would have almost a 30% lower mortality than patients in hospitals in which only 30% of nurses had baccalaureate degrees, and nurses cared for an average of eight patients. The results indicated there was value in using BSN-prepared nurses in these hospitals, whereas reducing nursing staff may have a negative impact on patient outcomes. We need more research on this critical topic to better understand education, quality care, and improvement of practice.

The AACN also supports baccalaureate-prepared nurses as essential to quality health. Its current data indicate the following patient outcomes and care provided by BSN nurses (2023):

- 24% greater odds of surviving cardiac arrest

- 25% lower odds of mortality

- 10% lower odds of death in patients with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias

- 32% decrease in surgical mortality cases

- 8% decrease in length of stay

With increasing interest in BSN-prepared nurses since early studies and more emphasis in the profession on completion of the BSN in the last few years, many more hospitals have implemented initiatives to hire only RNs with BSN degrees and to encourage staff members without BSN degrees to return to school. Studies such as the ones mentioned here have had an impact on increasing hospital support for RNs with BSN degrees. This decision by hospitals, however, is highly dependent on the availability of RNs with a BSN degree in the local area and has also been influenced by the Magnet Recognition Program®, which supports the BSN degree as a requirement for initial practice, though it does make this a requirement to receive Magnet recognition. In recognition of the importance of education, Magnet hospitals require that nurse managers and other nurse leaders hold a baccalaureate or higher degree at the time the HCO applies for Magnet status (ANCC, 2023).

| Stop and Consider 1 |

|---|

| Does the question of the best education entry point for nurses continue to be a challenge? What do you think about this issue? |

Types of Nursing Education Programs

Nursing is a profession with a complex educational pattern: It has many different entry-level pathways to the same license to practice and many different graduate programs. The following content provides descriptions of the major nursing education programs. Because several types of entry-level nursing programs exist, this complicates the issue and raises concerns about the best way to provide education for nursing students. Graduates of all three types of prelicensure programs (diploma, associate degree, baccalaureate) must successfully complete the same NCLEX-RN licensing examination to obtain licensure.

Diploma Schools of Nursing

Diploma schools of nursing still exist, but there are less than 100 programs. Many of these programs have transitioned to other types of degree programs-for example, by forming partnerships with colleges or universities where students might take some of their courses and partnering with ADN and BSN programs. Some have closed or converted into associate degree and baccalaureate programs. These programs still interest some employers when they are short of staff and degree programs are not meeting these needs. The Association of Diploma Schools of Professional Nursing represents these schools. Diploma schools are accredited by the NLN. Graduates take the same licensing exam as graduates from all the other types of nursing programs. The nursing curriculum is similar; the graduates need the same nursing content for the licensing exam. The students, however, typically have fewer prerequisites, particularly in liberal arts and sciences, though they do have some science content. Curricula requirements may vary in these schools because some schools allow students to take some of their required courses in local colleges.

Associate Degree in Nursing

Programs awarding an associate degree in nursing (AD/ADN) began when Mildred Montag, a nurse educator, published a book on the need for a different type of nursing program-a 2-year program that would be established in community colleges (Montag, 1959). The first programs opened in 1958. At the time Montag created her proposal, the United States was experiencing a shortage of nurses. For students, ADN programs are less expensive and shorter. The percentages of ADN and BSN programs vary from state to state. There is conflict about focusing only on BSN graduates. “The NLN advocates multiple entry points while the AACN supports BSN-entry. Greater than 50% of today's new nurses begin their careers by earning a two-year associate degree in nursing through which they achieve the requisite academic and clinical foundation to pass the licensing exam to start practice” (2018).

Montag envisioned the ADN as a terminal degree, but this perception has since changed, with the degree now typically viewed as part of a career mobility path. The RN-BSN or BSN completion programs are a way for ADN graduates to complete the requirements for a BSN. There are also LPN-ADN and LPN-BSN programs to assist licensed practical nurses in expanding their career path toward meeting requirements for registered nurse licensure. Typically, in these programs, nurses work for a time and then go back to school, often on a part-time basis, to complete a BSN in a university-level program. Some prerequisite courses must be taken before these students enter most BSN programs. Examples of additional nursing courses these students may take in the RN-BSN program are health assessment, public/community health with clinical practice, leadership and management, research/evidence-based practice, and health policy. Until recently, these students rarely took additional clinical courses, as this is not the major focus of the RN-BSN programs; however, all programs accredited by the AACN must now include some clinical practice experiences or a practicum. The Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (AACN, CCNE, 2023), an accrediting body for the AACN, defines clinical practice experiences as “planned learning activities in nursing practice that allow students to understand, perform, and refine professional competencies at the appropriate program level” (p. 1). The content typically included for the clinical experience is public/community health, focusing on what these students typically did not cover in their ADN program. Today, many of the RN-BSN programs offer courses online, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, nursing education moved many of its courses to e-learning to allow students to continue their education. There were also struggles to meet clinical practice experience requirements, which are required for some of the nursing courses and part of graduation requirements. The type of clinical experiences can vary greatly; however, not requiring clinical practice experiences in an RN-BSN program may be a problem for students who want to later complete a graduate nursing degree.

ADN and BSN programs have increased their efforts to partner with each other to provide a seamless transition from one program to the other. Establishing an articulation agreement describing partner responsibilities, benefits to the students, and how the students meet the expected BSN outcomes or competencies clarifies these partnerships (AACN, CCNE, 2019). “Articulation agreements are important mechanisms that enhance access to baccalaureate-level nursing education. These agreements support educational mobility and facilitate the seamless transfer of academic credit between associate degree (ADN) and baccalaureate (BSN) nursing programs” (AACN, 2019). Academic progression supports “lifelong learning through the attainment of academic credentials” and is an important element for all types of nursing education programs (OADN, ANA, 2015, p. 5; AACN, 2023c). Articulation agreements are used to provide options for educational mobility and facilitate the seamless transfer from one nursing degree program to another. State law may mandate these agreements, which may be partnerships between individual schools or may be part of a statewide articulation plan to facilitate a more efficient transfer of credits. Typically, in these partnerships, students spend their first 2 years in the ADN program and then complete the last 2 years of the BSN degree in the partner BSN program. In these types of programs, the participating ADN and BSN programs collaborate on the curriculum and determine how to best transition students. One benefit of this model is for the first 2 years students pay the community college fees, which are lower than university fees. Another advantage is that if there is no BSN program in a community, students have the option of staying within their own community while they pursue a nursing degree and then transitioning to a more distant BSN program or completing the BSN online.

Baccalaureate Degree in Nursing

The idea for the baccalaureate degree in nursing, an entry-level degree, was introduced in the Goldmark Report (Goldmark, 1923), although it took many years for this recommendation to have an impact on nursing education. Some of the original programs took 5 years to complete, with the first 2 years focused on liberal arts and science courses, followed by 3 years in nursing courses. Most BSN programs have changed to a 4-year model, with various configurations of liberal arts and sciences and then 2 years in nursing courses. Some schools introduce students to nursing content during the first 2 years, but typically, the amount of nursing content is limited during this period. In some colleges of nursing, students are not formally admitted to the school/college of nursing until they complete the first 2 years, although the students are in the same university. BSN programs may be accredited by the NLN or through the AACN, both of which have accrediting services. (More information about accreditation appears later in the chapter.) The licensure exam is taken after the successful completion of the BSN program. A BSN is required for admission to a nursing graduate program, and this has influenced more nurses without BSN degrees to return to school to get the degree.

The movement of many nursing schools into the university setting was not all positive. Nursing programs lost their strong connection with hospitals. Rather than establish different educational models with hospitals, the nursing education community sought to get away from the control of hospitals and move to an academic setting; however, now, nursing educators and students are often more like visitors in hospitals with little feeling of partnership and connection. This has an impact on clinical experiences, in some cases limiting effective clinical learning. During the COVID-19 pandemic, nursing education emphasized more academic-practice partnerships to cope with the many problems encountered in providing effective clinical practice for students. This experience may influence improvements in the academic-practice relationship postpandemic.

Master's Degree in Nursing

Graduate education and the evolution of the master's degree in nursing (MSN) have a long history. Early in the development of graduate-level nursing, it was called “postgraduate education,” and the typical focus areas were public health, teaching, supervision, and a few clinical specialties. The first formal graduate program was established in 1899 at Columbia University Teachers College (Donahue, 1983). The NLN supported the establishment of graduate nursing programs, and these programs developed in great numbers and, over time, developed new models. For example, some of the early programs, such as Yale School of Nursing, admitted students without a BSN who had a baccalaureate degree in another major. Today, this is very similar to the accelerated nursing programs or direct entry programs in which students with other degrees are admitted to a BSN program that is shorter, covering the same basic entry-level nursing content but with an accelerated approach. “The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that more than 275,000 additional nurses are needed from 2020 to 2030, and that employment opportunities for nurses will grow at 9 percent, faster than all other occupations from 2016 through 2026” (BLS, 2023). To reach this number, nursing education will need to develop methods to attract students and retain them to successful completion of the nursing degree. This requires quality education to prepare nurses to practice effectively. The accelerated degree program for nonnursing graduates has been used to attract more students, and schools of nursing should continue to offer this degree at both the baccalaureate and master's degree levels to increase the number of nursing graduates (AACN, 2023d). These students are typically categorized as graduate students because of their previous baccalaureate degree, even though the degree is not in nursing. Even so, they must complete prelicensure BSN requirements, including successful completion of the licensure exam, before they can enroll in nursing graduate clinical courses, and in some cases, they are not admitted to the nursing graduate program automatically until completion of a direct entry program. They must apply to the program in the same manner as any student who wants to attend a graduate program in nursing.

Master's degrees in nursing programs have evolved since the 1950s. The typical length for a master's program is 2 years, and students may attend full time or part time. The following are examples of master's degree programs:

- Advanced practice registered nurse(APRN): This is a job title that requires a minimum of a master's degree that can be offered in any clinical area, but typical areas are adult health, pediatrics, family health, women's health, neonatal health, and psychiatric-mental health. APRN graduates take certification exams in their specialty area and must then meet specific state requirements, such as for prescriptive authority, which gives them limited ability to prescribe medications. These nurses usually work in independent roles. The American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) provides national certification exams for advanced practice registered nurses in a variety of areas. APRNs treat and diagnose illnesses, advise the public on health issues, manage chronic disease, and engage in continuous education to remain ahead of technological, methodological, or other developments in the field. Historically, APRNs have completed at least a master's degree in addition to the initial nursing education and licensing required for all RNs, but this is changing. Examples of some other APRN roles include certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA), certified nurse-midwife (CNM), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), and certified nurse practitioner (CNP) (ANA, 2020). All these nursing positions are important in health care; for example, APRNs may serve as primary care providers and are at the forefront of providing preventive care services to the public (AACN, 2023e). See the section “Doctor of Nursing Practice” that follows regarding changes in requirements for APRNs.

- Clinical nurse specialist (CNS): This master's degree can be offered in any clinical area. Specialty exams may also be taken. These nurses usually work in hospital settings. The ANCC provides national certification for CNSs in a variety of areas, as discussed later in this chapter.

- Certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNA): This role requires a master's degree and is not offered at all colleges of nursing; however, over time, the requirements have changed. The Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Program, as part of the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists, focuses on the accreditation and certification of these programs. This educational program has been transitioning to Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) degree. Currently, nurse anesthetist programs must change to DNP by 2025. Because of this potential change, students entering advanced practice programs should consider the DNP. The other option is a Doctorate of Nursing Anesthesia Practice (DNAP). Both degrees are clinical practice doctorates, not “research-based doctorates.” “The most important difference between the two degrees will be for those who have a goal of obtaining a university faculty position after completion of the degree. For some state universities the DNAP will not be recognized as a terminal degree, and thus graduates who seek faculty positions will not be eligible for tenure. Aside from this, the differences between the 2 degrees are somewhat minimal” (TheCRNA, 2017).

- Certified nurse-midwife: This master's degree focuses on midwifery-pregnancy and delivery-as well as gynecologic care of women and family planning. These programs are accredited by the American College of Nurse-Midwives.

- Clinical nurse leader (CNL): This is one of the newer master's degrees, which prepares nurses for leadership positions that have a direct impact on patient care. The CNL is a provider and a manager of care at the point of care for individuals and cohorts. The CNL serves as a nurse leader and designs, implements, and evaluates patient care by focusing on care coordination, outcomes measurement, transitions of care, interprofessional communication and team leadership, risk assessment, implementation of best practices (evidence-based practice), and quality improvement. CNLs delegate and supervise care provided by the healthcare team, including licensed nurses, technicians, and other health professionals, and advocate for patients (AACN, 2023f). Certification is available for CNLs.

- Master's degree in a functional area: This type of master's degree focuses on the functional areas of administration or education. It was more popular in the past, but with the growing need for nursing faculty, there has been a resurgence of master's programs in nursing education (AACN, 2023g). In some cases, nursing colleges offer certificate programs in nursing education. In these programs, a nurse with a nursing master's degree may take a certain number of credits that focus on nursing education, and if the nurse successfully completes the NLN certification exam, the nurse is then a certified nurse educator. This provides the nurse with additional background and experience in nursing education.

Doctor of Nursing Practice

The DNP is the newest nursing degree and is a practice-focused doctoral nursing program that prepares leaders for nursing practice, including both clinical and nonclinical care (AACN, 2023h). The latter emphasis on nonclinical care was a factor in the development of many DNP programs (Mundinger & Carter, 2019). The DNP is not a traditional PhD program, although nurses with a DNP degree are also called “doctor.” However, this does not represent the same title as someone with a PhD or a medical degree. This position has been controversial within nursing and within health care, particularly among physicians (Cronenwett et al., 2011). Over time, it has become more accepted and, as noted in this content, now required more for certain specialty graduate roles.

Some of the reasons why the DNP degree was developed relate to the process for obtaining an APRN master's degree, which requires many academic credits and clinical hours. It was recognized that students should be getting more credit for their coursework and effort. Going on to a DNP program allows them to apply some of this credit toward a doctoral degree. Three-hundred and fifty-seven DNP programs are located across the United States in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, with planning being done for 106 new programs. Since the DNP was first offered 17 years ago, 60,500 nurses have graduated with this degree. The 407 DNP programs are currently enrolling students at schools of nursing nationwide, and an additional 106 new DNP programs are in planning stages (49 postbaccalaureate and 47 postmaster's programs). (AACN, 2023h). This will continue as more master's degree programs for APRNs change to DNP programs, and there is more need for nurse leaders with scientific knowledge and expertise in quality care at all levels in HCOs-all types of HCOs. It has been recognized that the DNP prepares advanced practice nurses for leadership across complex HCOs (Bowie et al., 2019). However, there is need to consider the clinical and nonclinical aspects of the DNP degree in order to ensure that APRNs can practice effectively and also that the public is not confused by nurses with a DNP degree and those who are more clinically directed-“The nursing profession must address the potential consequences of reducing the overall number of advanced practice nurse clinicians by eliminating the clinical master's degree programs without establishing a reasonable number of clinical doctoral programs” (Mundinger & Carter, 2019, p. 61).

Research-Based Doctoral Degree in Nursing

The doctoral degree (Doctor of Philosophy-PhD; research-based doctorate) in nursing has had a complicated development history. The Doctor of Nursing Science (DNSc) was first offered in 1960, but this degree program has since transitioned to other types of doctoral programs. There were PhD programs in nursing education as early as 1924, with New York University establishing the first PhD program in nursing practice in 1953. More students need to enter these programs, and this has an impact on nursing faculty because schools of nursing want faculty with doctoral degrees. Someone with a PhD is not always required to teach but is encouraged to do so. Nurses with PhDs usually are involved in research, although a nurse at any level can be involved in research and may or may not teach. PhD study typically takes place after receiving a master's degree in nursing and includes coursework and a research-focused dissertation. This process can take 4 to 5 years to complete, depending on the completion of the dissertation. Nurses with PhDs may be called “doctor”; this is not the same as the “medical doctor” title but rather a designation or title indicating completion of academic doctoral work in the same way that an English professor with a doctorate is called “doctor.” Supporting the need for more nurses with PhDs, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation initiated a program, the Future of Nursing Scholars, to provide funding and implement a 3-year PhD program that also provides opportunities for mentorship and networking to expedite the development of nursing scholars (Newhouse et al., 2023). Nurses who have participated in this program have found this helpful, but they also note that more information needs to be shared about the differences between the PhD and the DNP with greater clarification of the benefits of the nurse scientist role.

Some schools of nursing now offer BSN-PhD or BSN-DNP option. This means the student does not have to obtain a master's degree prior to entering the program, and the students typically enter the process as BSN students and complete with a PhD or DNP degree. The goal is to increase the number of nurses with doctoral degrees as terminal degrees by encouraging nursing students to make this career decision early.

| Stop and Consider 2 |

|---|

| We have confusion in the profession over roles, degrees, and how other healthcare providers view nursing due to these issues, both at the undergraduate and the graduate level. |

Nursing Education Associations

There are three major nursing education organizations, each with some variation in their focus. These organizations are the NLN, the AACN, and the OADN, described in the following sections.

National League for Nursing

The NLN is older than the AACN. It represents several types of registered nurse programs (diploma, ADN, BSN, master's) and vocational/practical nurse programs. Accreditation of nursing education programs is discussed in a later section of this chapter. The NLN offers educational opportunities for its members (individual membership and school of nursing membership) and addresses policies and standards related to nursing education. Its mission is to “promote excellence in nursing education to build a strong and diverse nursing workforce to advance the health of our nation and the global community” (NLN, 2022b).

American Association of Colleges of Nursing

The AACN is the national organization that represents baccalaureate and graduate programs in nursing, including doctoral programs. It began in 1969 with 121 member institutions and now has approximately 865 members (public and private schools/colleges of nursing), representing 530,000 students and 54,000 faculty (AACN, 2023i). Its activities include educational research, governmental advocacy, data collection, publishing, and initiatives to establish standards for baccalaureate and graduate degree nursing programs, including implementation of the standards. The AACN goals for 2023-2025 are as follows: The AACN is (1) the driving force for innovation and excellence in academic nursing; (2) the leading partner in advancing improvements in health, health care, and higher education; (3) a resolute leader for advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion within nursing; and (4) the authoritative source of knowledge to advance academic nursing through information curation and synthesis (AACN, 2023j; 2023k). The organization also offers accreditation for baccalaureate and master's degree nursing programs, as described in another section in this chapter.

Organization for Associate Degree Nursing

The OADN began in 1984 after Mildred Montag proposed the ADN degree in 1952. The OADN, formerly known as N-OADN, is the organization that advocates for associate degree nursing education and practice. Its major goals are to collaborate in supporting quality associate degree nursing education, recognize excellence in associate degree education, support effective faculty teaching and nursing education research, support funding for students and faculty education, provide leadership for associate degree education, and advocate for the associate degree in nursing (OADN, 2023, 2020). The organization supports the academic progression of its graduates so that they can reach their full potential. The organization does not offer accreditation services. The NLN accrediting organization, the Commission for Nursing Education Accreditation (CNEA), provides accreditation for OADN programs.

| Stop and Consider 3 |

|---|

| There are three nursing education organizations, which may be due to the confusion over the degree programs and how they relate to one another. |

Quality and Excellence in Nursing Education

There is greater emphasis today on quality health care, as discussed in this text, but also, for us to have quality care, we need to have healthcare providers who meet standards for quality performance. This requires consideration of the quality of nursing education programs.

Nursing Education Standards

Nursing education standards are developed by the major nursing professional organizations that focus on education: NLN, AACN, and OADN. The accrediting bodies of the NLN and the AACN also set nursing education standards as part of their accredited nursing education programs. State boards of nursing are involved as well. In addition, colleges and universities must meet certain standards for nonnursing accreditation at the overall college or university level. Standards guide decisions, organizational structure, process, policies and procedures, budgetary decisions, admission and student progression, evaluation/assessment (program, faculty, and student), curriculum, and other academic issues. Critical standard documents published by the AACN are The Essentials, covering baccalaureate, master's, and DNP degrees (AACN, 2021). The baccalaureate Essentials emphasize the three roles of the baccalaureate generalist nurse. These standards, which are competency-based, include student-learning outcomes expected for nursing prelicensure graduates. These standards have recently been revised, as discussed in the following content. In addition, the CNEA is also revising its standards, and updates can be found on the NLN CNEA website (NLN, 2023a).

The 2021 versions of AACN (CCNE) and NLN (CNEA) standards (baccalaureate degree, master's degree, and clinical doctorate) are the newest editions of accreditation standards (AACN, 2021; NLN, 2023a). The AACN notes: “The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education is a carefully crafted document that was developed following a lengthy, inclusive, and iterative process with input from hundreds of faculty and deans as well as from multiple organizational stakeholders. The Essentials Task Force spent many months engaged in listening, discerning dialogue, and compromise to ensure quality, future-thinking standards for professional nursing education. A driving context for the Essentials Task Force was differentiating between ‘change' and ‘transformation,' which are often used interchangeably. Change fixes the past; it modifies behaviors. Transformation creates the future; it modifies values, core beliefs, and desires. The re-envisioned Essentials using a competency-based education model represents transformation, a bridge to the future of academic nursing” (AACN, 2021). The new edition includes the following key information that is required for all nursing education programs accredited by the AACN through its accrediting body, the CCNE. The new standards emphasize four spheres of care: (1) disease prevention/promotion of health and well-being, (2) chronic disease care, (3) regenerative or restorative care, and (4) hospice/palliative/supportive care (AACN, 2021). The 10 domains or nursing focus areas identified in The Essentials are (pp. 11-12):

- Knowledge of nursing practice

- Person-centered care

- Population health

- Scholarship for nursing practice

- Quality and safety

- Interprofessional partnerships

- Systems-based practice

- Information and healthcare technologies

- Professionalism

- Personal, professional, and leadership development

Concepts that are interrelated with the competencies and domains are clinical judgment, communication, compassionate care, diversity/equity/inclusion, ethics, evidence-based practice, health policy, and social determinants of health (p. 12-13). The competencies are described in the AACN Essentials website, along with further information about the domains and concepts (AACN, 2021).

NLN Excellence in Nursing Education

The NLN Hallmarks of Excellence initiative identifies hallmarks or indicators of nursing education excellence focused on students, diverse and prepared faculty, continuous quality improvement, innovative and evidence-based curriculum, evidence-based learning approaches, resources supporting goals, pedagogical scholarship, and leadership supported by the NLN Center for Excellence (NLN, 2023b, c). These indicators are applied in two of the NLN's programs that recognize nursing education excellence and include the hallmarks.

The NLN Center for Innovation in Education Excellence identifies schools of nursing that demonstrate they have achieved “a level of excellence in a specific area. Through public recognition and distinction, the program acknowledges the outstanding innovations, commitment, and sustainability of excellence these organizations convey” (NLN, 2022c). These schools commit to pursuing excellence in (1) student learning and professional development, (2) development of faculty expertise in pedagogy, and/or (3) advancing the science of nursing education. The Center of Excellence (COE) award is given to a school or college of nursing-not a program within a school-and remains in effect for 4 years. Schools may apply for continuing COE designation but must continue to meet all requirements and complete the review process. After this period, the school must be reviewed again to retain the COE recognition. This NLN initiative is a good example of efforts to improve nursing education, and it provides “creative educational simulation and curriculum integration advisory services, teaching and learning resources, and professional development opportunities” (NLN, 2022b). Two focus areas that are important to education and to current public health practice are simulation and care of vulnerable populations. In providing resources in these two areas, the NLN supports effective care and health equity.

A third example of the focus on nursing education quality is the NLN Academy of Nursing Education, which emphasizes excellence in nursing education by “recognizing and capitalizing on the wisdom of outstanding individuals in and outside the profession who have contributed to nursing education in sustained and significant ways” (NLN, 2020a). It selects nurse educator fellows who demonstrate significant contributions to nursing education in one or more areas (teaching/learning innovations, faculty development, research in nursing education, leadership in nursing education, public policy related to nursing education, or collaborative education/practice/community partnerships) and continue to provide visionary leadership in nursing education. The academy inducted its first nurse education fellows in 2007 and continues to do so annually.

The AACN and NLN nursing education accreditation bodies (CCNE and CNEA) have been very involved in assisting academic nursing programs with adaptations needed to cope with offering nursing degree education during the pandemic (AACN, 2020a; NLN, 2020b). There was major concern about the impact of offering didactic content and clinical practice experiences on faculty and student safety with recognition of the need for academic/practice partnerships during a time of public health crisis and resources to assist nursing education in meeting its goals. The organizations assisted schools and programs to meet the needs in a stressful environment; for example, the CCNE provided guidance to its accredited nurse residency programs, which have had to cope with changes related to the pandemic, and AACN and NLN provided additional faculty resources.

Focus on Competencies

In 2003, the IOM published the Health Professions Education report to address the need for education in all major health professions by describing critical common competencies. The development of this report was motivated by grave concerns about the quality of care in the United States and the need for healthcare educational programs to prepare professionals who provide quality care. “Education for health professions needs a major overhaul. Clinical education [for all healthcare professions] simply has not kept pace with or been responsive enough to shifting patient demographics and desires, changing health system expectations, evolving practice requirements and staffing arrangements, new information, a focus on improving quality, or new technologies” (IOM, 2003, p. 1). The core competencies are also emphasized in the Essentials of Baccalaureate Education; however, schools of nursing need to make changes to include the competencies and, in some cases, add new content to meet these needs.

The nursing curriculum should identify the competencies expected of students throughout the nursing program. There is greater emphasis today on implementing healthcare professions competencies, particularly the core competencies for all healthcare professions identified by the Institute of Medicine as part of its reports on quality care: (1) provide patient-centered care, (2) work in interdisciplinary/interprofessional teams, (3) employ evidence-based practice, (4) apply quality improvement, and (5) utilize informatics (IOM, 2003). This does not mean that profession-specific competencies are not relevant, such as the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN, 2023) competencies, which should also be implemented, but the IOM competencies recognize the existence of basic competencies that all healthcare professions should demonstrate. See Table 3-1 comparing the core healthcare profession competencies and QSEN competencies.

Table 3-1 Comparing the Five Healthcare Professions Core Competencies and the QSEN Competencies for NursesHealthcare Professions Core Competencies* | QSEN Competencies for Nurses** |

|---|---|

Provide patient-centered care. | Patient-centered care: knowledge, skills, attitudes |

Work on interdisciplinary [interprofessional] teams. | Teamwork and collaboration: knowledge, skills, attitudes |

Employ evidence-based practice. | Evidence-based practice: knowledge, attitudes, skills |

Apply quality improvement. | Quality improvement: knowledge, skills, attitudes |

Utilize informatics. | Safety: knowledge, skills, attitudes |

Informatics: knowledge, skills, attitudes | |

| Data from Institute of Medicine (IOM; 2003). Health Professions Education. A Bridge to Quality. The National Academies Press; QSEN Institute (2022). Pre-licensure Competencies. https://www.qsen.org/competencies-pre-licensure-ksas |

*Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2003). Health Professions Education. A Bridge to Quality. The National Academies Press. **QSEN Institute (2022). Pre-licensure Competencies. https://www.qsen.org/competencies-pre-licensure-ksas Students need to understand the expected competencies so that they can be active participants in the learning process to reach these competencies, which are used in evaluation and to identify the level of learning or performance expected of the student. Nursing is a profession-a practice profession-so performance is a critical factor. The ANA (2018) defines competency as “an expected and measurable level of nursing performance that integrates knowledge, skills, abilities, and judgment, based on established scientific knowledge and expectations for nursing practice” (p. 86). Competencies should clearly state the expected parameters related to the behavior or performance. The curriculum should support the development of student competencies by providing prerequisite knowledge and learning opportunities to meet the competency. The goal is a competent RN who can provide quality care. Supporting this view, the reenvisioning of the AACN Essentials (2021) includes a greater focus on competency-based education (Bartels, 2019):

This approach makes the student the center of learning, and the student holds some responsibility for his or her own learning. The 2021 AACN Essentials emphasize the following: “Competency-based education is a process whereby students are held accountable to the mastery of competencies deemed critical for an area of study. Competency-based education is inherently anchored to the outputs of an educational experience versus the inputs of the educational environment and system. Students are the center of the learning experience, and performance expectations are clearly delineated along all pathways of education and practice” (AACN, 2021, p. 5; 2023l). With the revision of the identification of the health professions core competencies by the IOM and associated identification of the QSEN competencies (see Table 3-1), the revision of the AACN standards connects the emphasis on these competencies. They are reflected in the standards (QSEN Institute, 2023; Wang et al., 2022). The standard domains and concepts described in this chapter are interrelated with all these initiatives. Curriculum A nursing program's curriculum is the plan that describes the program's philosophy, levels, student terminal competencies (outcomes or what students are expected to accomplish by the end of the program), and course content and course outcomes/objectives (described in course syllabi). Also specified are the sequence of courses and a designation of course credits and learning experiences, such as didactic courses (typically offered in a lecture/classroom, seminar setting, or both venues; in some cases, in online format or hybrid, combined face-to-face and e-learning) and clinical/practicum experiences. In addition, simulation laboratory experiences are included either at the beginning of the curriculum or throughout the curriculum. The nursing curriculum informs potential students what they should expect in a nursing program and may influence a student's choice of programs, particularly at the graduate level. It helps orient new students. The curriculum is also reviewed during the accreditation process and by state boards of nursing that are charged with oversight of schools of nursing within a state. To keep current, faculty need to review the curriculum regularly in a manner that allows for easy and timely changes and includes student input. Nursing education accreditation standards also have an impact on the curriculum; for example, The Essentials (AACN, 2021) provides guidelines for nursing curricula, prelicensure, and graduate programs. Didactic or Theory Content Nursing curricula may vary as to titles of courses, course descriptions and objectives/learning outcomes, sequence, number of hours for didactic content, and clinical experiences, but there are some constants even within these differences. To ensure consistency in the practice of nursing and prepare for the licensure exam, nursing content needs to include the following broad topical areas:

Many schools offer courses focused on other topics, such as informatics and genetics, though some opt to integrate this content into several courses. Quality improvement content is often weak, even though it is now considered critical knowledge that every practicing nurse needs to have if care is to be improved and should be integrated throughout the curriculum. Nursing content may be provided in clearly defined courses that focus on one overall topical area, or it may be integrated with multiple topics. Clinical experience/practicum may be blended with related didactic content-for example, pediatric content and pediatric clinical experience-such that they are considered one course; alternatively, the clinical/practicum and didactic content may be offered as two separate courses, typically in the same semester. Faculty that teach didactic content may or may not teach in the clinical setting. Practicum or Clinical Practice Experience Practicum, or clinical practice experience, is a critical component of a nursing curriculum. These experiences must be planned, correlate with the curriculum, require intensive faculty supervision, time and effort to facilitate effective learning, and focus on active student engagement in the experiences. Extensive faculty effort and coordination with clinical sites are required for effective planning, implementing, and evaluating student clinical experiences. A critical issue today for many schools is access to clinical sites. This has led to using various methods to alleviate problems in accessing clinical experience options to ensure effective clinical experiences for students-some methods have been more successful than others. The hours for practicum or clinical experiences can be highly variable within one school and from school to school (for example, the number of hours per week and sequence of days, such as practicum on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m.). Some schools offer 12-hour clinical sessions. This type of student schedule conflicts with the acknowledgment that 12-hour work shifts may lead to staff fatigue and an increased number of errors. Some schools offer clinical experiences in the evenings, at night, and on weekends, but these schools must ensure that there is student access to faculty and that staff are prepared to assist students. It is important for students to understand the time commitment and scheduling related to clinical experience requirements, which have a great impact on students' personal lives, time with family, and social relationships. If a student is employed while going to school, scheduling and transportation may be challenging for the student, as students will be in a variety of clinical sites throughout their nursing program experiences. In addition, clinical experiences require preparation time. The types of clinical settings are highly variable and depend on the objectives and the available sites. Typical types of settings are acute care hospitals (all clinical areas); mental health/psychiatric hospitals; pediatric hospitals; women's health (may include obstetrics) clinics; public/community health clinics and other health agencies; home healthcare agencies; hospice centers, including freestanding sites, hospital-based centers, and patient homes; schools; camps; long-term care and rehabilitation facilities; health-oriented consumer organizations, such as the American Diabetes Association; health mobile clinics; homeless shelters; doctors' offices; clinics of all types; ambulatory surgical centers; emergency centers; businesses with occupational health services; and many more. In acute care, there is typically a group (8 to 10 students) assigned to a faculty member in one clinical area for hospital experiences, and faculty are present during the experience. In other settings, particularly public/community healthcare settings, faculty visit students at the site because, typically, only a few students are at each site, with the clinical group of as many as 10 students spread out at different sites. The ratio of students to faculty in clinical settings may vary depending on individual state board of nursing requirements. The number of hours per week in clinical experiences increases each year in the program, with more hours assigned at the end of the program. COVID-19 had a major impact on educational experiences for students. For example, faculty may have had problems ensuring clinical experiences due to clinical site availability, scheduling difficulties, faculty and preceptor coverage, and the need for personal protective equipment (PPE) while in the clinical site. The experience of the pandemic required schools and clinical sites to work together to ensure effective clinical learning experiences for students, sometimes using innovative methods for scheduling, access to clinical experiences, and supervision. The National Council for State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) examined the experience and published an extensive analysis in its journal, The Journal for Nursing Regulation. The summary comments note the following: “The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on prelicensure nursing education, leading to widespread disruptions that may have implications for nursing students' learning and engagement outcomes. Understanding how the rapid shift to online and simulation-based teaching methods has affected new graduates' clinical preparedness is critical to ensure patient safety moving forward” (Martin et al., 2023, p. S3). “RN programs around the country sought to address the nearly unparalleled challenges they confronted daily over the past 3 years. This study stands as the most comprehensive assessment of prelicensure nursing education in the United States since the onset of COVID-19. It extends knowledge by linking potential deficiencies in students' didactic and clinical education during the pandemic and their early career preparedness and clinical competence, and in doing so illuminates the possible implications for patient safety moving forward” (Martin et al., 2023, p. S46). Nursing programs may use preceptors in the clinical settings in both undergraduate and graduate programs. In entry-level programs, preceptor experiences are typically used toward the end of the program, but some schools use preceptors throughout the program for certain courses, such as in master's programs. Nursing faculty and management must collaborate to develop preceptor experiences with staff assisting. A preceptor is an experienced and competent staff member (for example, an RN staff nurse may be a preceptor for undergraduate students, APRN graduate or medical doctor for APRN students, CRNA or a certified nurse-midwife for graduate nursing students in these specialties). Preceptors should have formal training to function in this role. The preceptor serves as a role model and a resource for the nursing student and guides learning. The student is assigned to work alongside the preceptor. Faculty provide overall guidance to the preceptor regarding the nature of, and objectives for, the student's learning experiences, monitor the student's progress by meeting with the student and the preceptor, and are on call for communication with the student and preceptor as needed. The preceptor participates in evaluations of the student's progress, along with the student, but the faculty member is responsible for student evaluation. The state board of nursing may dictate how many hours may be assigned to preceptor experiences for undergraduate students. At the graduate level, the number of preceptor hours is much higher. Distance Education/E-Learning Distance education/e-learning, which is typically offered online, has become quite common in nursing education. Although not all schools offer courses in this manner, this changed due to COVID-19 as there was a greater need to continue courses, and yet in-person sessions were not possible. We do not yet know the long-term impact of this increase in alternative course methods-will schools of nursing continue to offer this option after the pandemic is resolved, or what might happen if COVID-19 resurges? Distance education occurs when the faculty and student are not in the same place, and the teaching-learning experiences may be synchronous or asynchronous, typically using technology, such as the internet (AACN, 2023m): “All nursing education programs delivered solely or in part through distance learning technologies must meet the same academic program and learning support standards and accreditation criteria as programs provided in face-to-face formats, including the following: