Healthcare delivery is a complex process and system, which includes many types of healthcare provider organizations, such as acute care organizations (hospitals), ambulatory care centers (clinics), private provider offices, public/community health facilities and services, home healthcare agencies, hospice agencies, extended care facilities, and so on. This chapter focuses on the most common type of healthcare organization (HCO): the acute care hospital. This does not mean that other types of HCOs, such as in public/community health, are not important; however, nursing students typically spend more of their clinical time in hospitals. Many of the organizational elements of a hospital are similar to those of other HCOs but may vary depending on the organization and purpose. The content in this chapter explores current issues related to hospitals and hospital organization and function and the hospital provider team, and introduces content about healthcare financial issues and the nursing organization and functions within the hospital.

Many factors affect hospitals, leading them to change their services, collaborate with others in their communities, realign their organization with other organizations, hospital closures due to financial issues, meet quality improvement requirements, and so forth. Examples of factors that influence hospitals today include the following:

- Increase in healthcare costs

- Shortage of healthcare providers (may be geographic or HCO specific)

- Uninsured and underinsured patients who are unable to pay for their care

- Recognition of the importance of diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA)

- Growing diversity in patients and the healthcare workforce-for example, increasing the need for interpreter services, the importance of cultural competency, and greater representation of ethnic groups in the healthcare workforce

- Compromised access to care for some individuals, leading to healthcare disparities and poor health outcomes

- Advances in medical technology that can improve care but may be costly, require special staff training, and may not be accessible to patients who cannot pay for them

- Impact of quality improvement data and requirements that may lead to changes

- Greater use of informatics in documentation and for other healthcare informational purposes

- Increasing use of digital health

- Increasing consumerism-more knowledgeable patients who demand more information and participation with greater emphasis on patient/person-centered care (PCC)

- Hospital mergers and closings, altering access to services

- Changes in the number of available beds; changing specialty services (for example, increasing the number of intensive care beds, eliminating obstetric services, offering home healthcare services)

- Changes in patient demographics that require reassessment of types of services offered and how the services are provided (for example, increasing services for older adults, immigrants, and single parents; expanding clinic hours to facilitate access; and so on)

- Need to integrate more public and community health

- Legislation related to healthcare delivery

- Impact of emergency/disaster needs, such as the COVID-19 pandemic increasing the need for intensive care, staff stress, and so on; emphasizing public health emergency preparedness

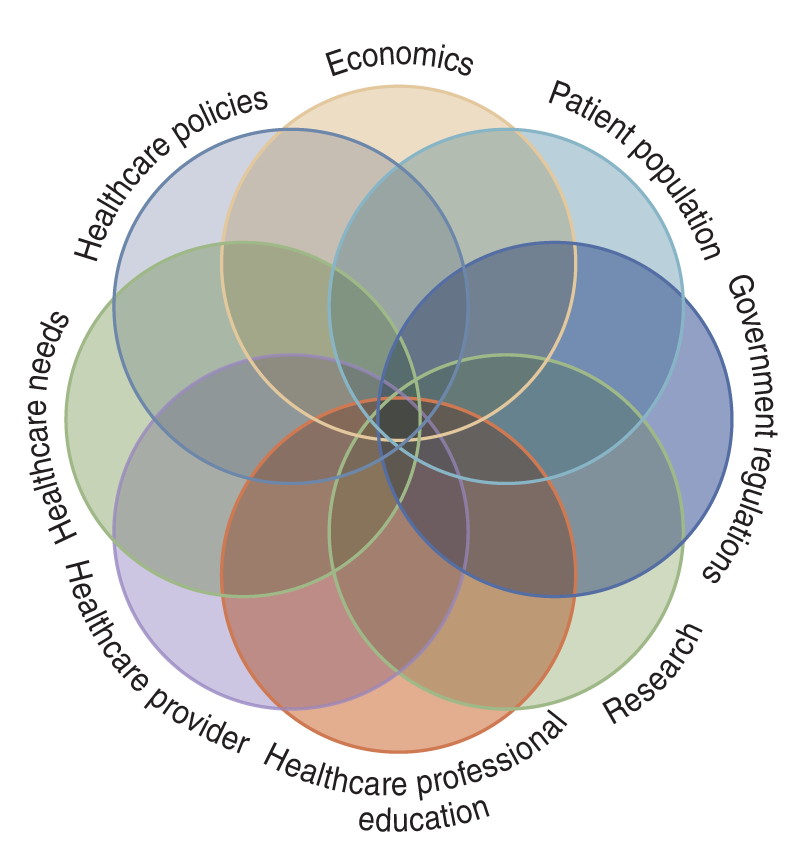

Examples of key influences on health care are highlighted in Figure 8-1. Exhibit 8-1 identifies examples of organizations that influence healthcare delivery.

Figure 8-1 Influences on healthcare delivery.

A complex Venn diagram with overlapping circles depicts Economics, Patient population, Government regulations, Research, Healthcare professional education, Healthcare provider, Healthcare needs, and Healthcare policies. The overlapping regions highlight the interconnectedness of these factors.

| Exhibit 8-1 Examples of Organizations Important to the Healthcare Delivery System |

|---|

|

Corporatization of Health Care: How Did We Get Here?

Using the term corporatization or “business” when referring to a hospital may seem strange; however, health care is a business-a very large, complex business. It provides services to most of the population at some time during a person's life, from birth to death. Hospitals have a very large employee pool, with nurses representing the largest percentage. Within a community, hospitals provide jobs for many people-both professionals and nonprofessionals; thus, they often represent one of the largest employment sectors. Within a community, HCOs may own or lease a large amount of property, purchase a large number of supplies and equipment, and pay taxes-all activities that bring income into a community. Typically, healthcare leaders hold significant positions in the business sector and the community. Healthcare consumes the largest amount of federal and state dollars through healthcare reimbursement programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid.

It is not uncommon to refer to hospitals as for-profit or not-for-profit. These terms can be confusing. The first critical point is that every hospital needs to make a profit, which means HCOs need to have money left over after expenses are paid. The distinguishing characteristic between for-profit and not-for-profit organizations is what the organization does with its profit. The assumption made by most people is all hospitals are not-for-profit organizations, but this is not correct. Many HCOs are for-profit corporations. Some of their profit must go to their stockholders/shareholders or to their owners. However, even not-for-profit organizations must also cover their operation costs and reinvest money in the hospital for maintenance, expand space and renovate, develop new services, purchase equipment and supplies, hire new staff, and so on. Not-for-profit organizations do not have stockholders/shareholders, but they still need to make a profit for the same reason that for-profit organizations need a profit: to cover expenses.

Knowing whether the hospital you work for is a for-profit or not-for-profit organization can help you understand why and how decisions are made. For example, if a hospital is burdened with a high number of nonpaying patients, the hospital may eventually spend more than it is making and thus be “in the red” when its debt increases. When this happens, the hospital may cut staff, limit new equipment purchases, control the use of supplies, fail to maintain equipment effectively, neglect facility maintenance needs and renovation, attempt to reconfigure services to attract paying patients, decrease staff education, and make other changes to improve the hospital's financial condition but this may have a negative impact on patients and on the staff. All HCOs need to be concerned with cost containment, but when the financial situation is weak, the organization needs to expand cost containment to manage its finances. A for-profit HCO must always have funds to pay stockholders or owners, and this consideration may have an impact on the availability of money for other purposes that affect nurses and nursing staffing, such as the issues mentioned here. Both for-profit and not-for-profit HCOs can experience financial difficulties.

| Stop and Consider 1 |

|---|

| Healthcare delivery is a business. |

The Healthcare Organization

Hospitals represent the largest type of HCO. Other types of HCOs are identified in Exhibit 8-2. Descriptions of an HCO should include information about the organization's structure, processes, staff, and organizational culture. Although most of the work done by registered nurses (RNs) is done in hospitals, many also work in other types of HCOs, with the percentage of RNs working in hospitals decreasing over recent years. Nurses work in all of the healthcare settings identified in Exhibit 8-2. Data from 2022 indicated that 30.85% of RNs worked in general medical and surgical hospitals, 14.87% in outpatient care settings, 11.31% in home healthcare services, 9.28% in nursing care facilities, and 7.50% in physician offices, representing small changes compared to 2019 (DOL, BLS, 2022).

| Exhibit 8-2 Types of Healthcare Organizations |

|---|

|

Hospitals can vary in their organizational structure, but there are some standard types of organizations. In the past, it was more common for hospitals to operate as single organizations. Now, more hospitals have formed complex organizations consisting of multiple hospitals, which may be spread across a state or even a national system with hospitals in multiple states. In some cases, these systems also include other healthcare entities, such as home healthcare agencies, rehabilitation centers, long-term care facilities, and freestanding ambulatory care centers to support a continuum of care between acute care and public and community health services. Most of the reasons for this change in hospital organization structure to include different services are related to financial issues and the survival of the organization-to keep patients in the system and increase services. Some communities have experienced multiple changes in their local hospitals, with hospitals merging with other hospitals or others trying to go it alone. The critical message is that hospitals are changing their overall organization, and it is not clear what the future holds for healthcare access in some communities.

Small hospitals with 100 or fewer beds and hospitals in rural areas are particularly vulnerable. They often have difficulty getting enough admissions and, therefore, often lose money. In addition, even though they may be small, they must keep costly equipment current by purchasing new equipment and maintaining their equipment, physical facilities, and an acceptable staffing level.

There are also community crises, public health emergencies, and disasters that require more services that may be costly, such as the services required for COVID-19 patients increasing the need for ventilators and other complex and protective equipment. If the community is struggling economically, this has an impact on patients paying for services with or without health insurance. The American Hospital Association (AHA) noted that there was a critical problem with hospital finances with more hospitals operating in the red due to COVID care due to the increased need for complex, staff intensive care and also the need to reduce services for non-COVID patients in order to provide these critical services for COVID (AHA, 2020; Stuart, 2020). Hospitals also need to maintain a certain level of staff, including staff with certain expertise and specialists (physicians, nurses, and others). This is not a business that can easily flex staff numbers and use a lot of temporary staff, and it takes time to orient new and temporary staff. These vulnerable hospitals, such as rural hospitals, may have problems recruiting RNs for their workforces because many RNs prefer to work in urban centers and in large, up-to-date hospitals, and similar problems occur with physicians. Schools of nursing in states with large rural areas partner with rural hospitals to improve student enrollment from these areas and, they hope, increase the RN pool in the workforce for these geographic regions. Such partnerships provide courses and clinical experiences in rural healthcare settings and may use virtual methods to facilitate access to nursing programs, making it easier for students and reducing student travel time to campus.

Healthcare spending is high, and it is important that the healthcare delivery system considers expenses and how money is used in the system. For example, in 2022, clinical waste represented 5.4-15.7% of national health spending. “Clinical waste is caused by failures of care delivery, failures of care coordination, and overtreatment” (Health Affairs, 2022). The issue of waste was identified as a major concern in the 2013 IOM report on U.S. health care and is now monitored, as seen in the 2022 data. The report indicated that there was a need to focus on the best care at a lower cost, not a higher cost (IOM, 2013). The report Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America described the system in this way: “Health care in America presents a fundamental paradox. The past 50 years have seen an explosion in biomedical knowledge, dramatic innovation in therapies and surgical procedures, and management of conditions that previously were fatal, with ever more exciting clinical capabilities on the horizon. Yet, American health care is falling short on basic dimensions of quality, outcomes, costs, and equity” (IOM, 2013, p. 1). Organizations involved in healthcare quality, such as the Institute for Health Improvement (IHI), also noted that there is a need to reduce waste and cost in the U.S. healthcare system. “Waste is more than just ordering too many supplies. It can include over-diagnosis, unnecessary diagnostics, and unnecessary surgery. For example, to avoid waste there's been a big shift away from doing invasive diagnostic tests for things like radiology studies for mild lower back pain or pap smears every year for healthy younger women. These are tests that turn up a lot of false positives and expose patients to unnecessary risks. They also cost a lot of money and cause worry for patients without leading to improved outcomes resources” (IHI, 2019). Waste also relates to errors when time and supplies may be wasted. HCOs need to “identify and address clinical waste, including through state-level data collection and education efforts. Research on medical error also highlights a range of interventions with the potential to reduce waste and improve quality, including physician resident handoff programs, the use of surgical checklists, and other interventions to build “safety cultures” in hospitals. Identification and reduction of medical waste must be a key component of any broad strategy to moderate health care spending growth and improve patient outcomes” (Health Affairs, 2022). There are many strategies that can be used to decrease waste and improve care, as illustrated by some of these methods. Reducing waste also means that monies that might have been lost in waste may be needed for other purposes in healthcare delivery, supporting effective and efficient services (Bogan, 2019).

In summary, compared to other countries, the United States is paying more for less, resulting in poorer healthcare outcomes than are found in other industrialized nations. The complex U.S. healthcare delivery system must better manage costs while simultaneously ensuring quality, evidence-based care. Trying to achieve this balance leads to more changes in the healthcare delivery system and impacts nursing. Nurses need to be involved in improving and balancing the need for financial support and quality care.

Structure and Process

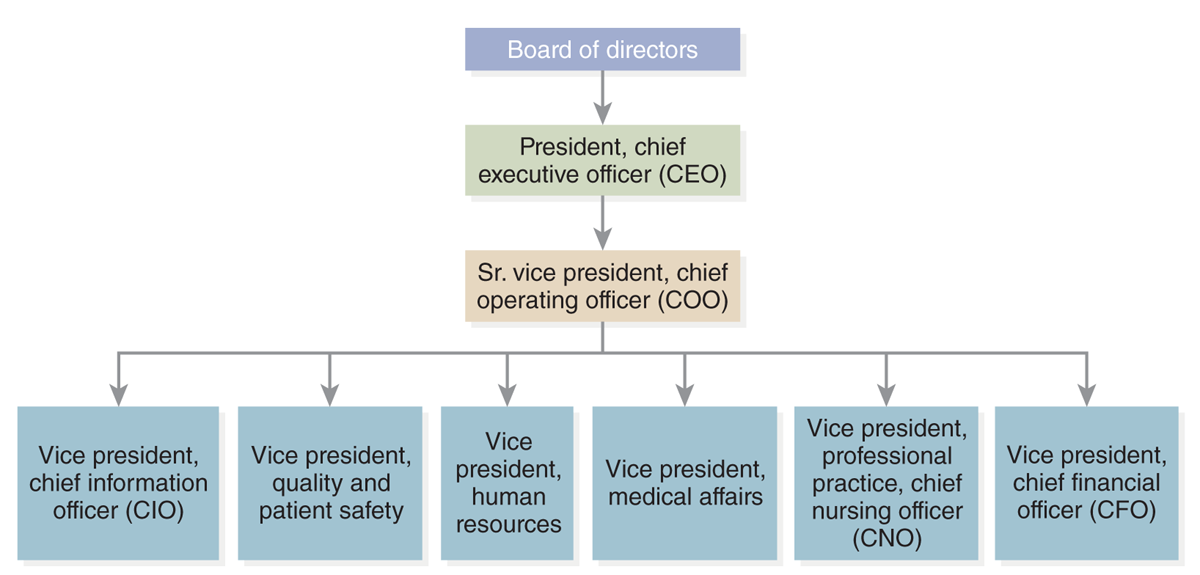

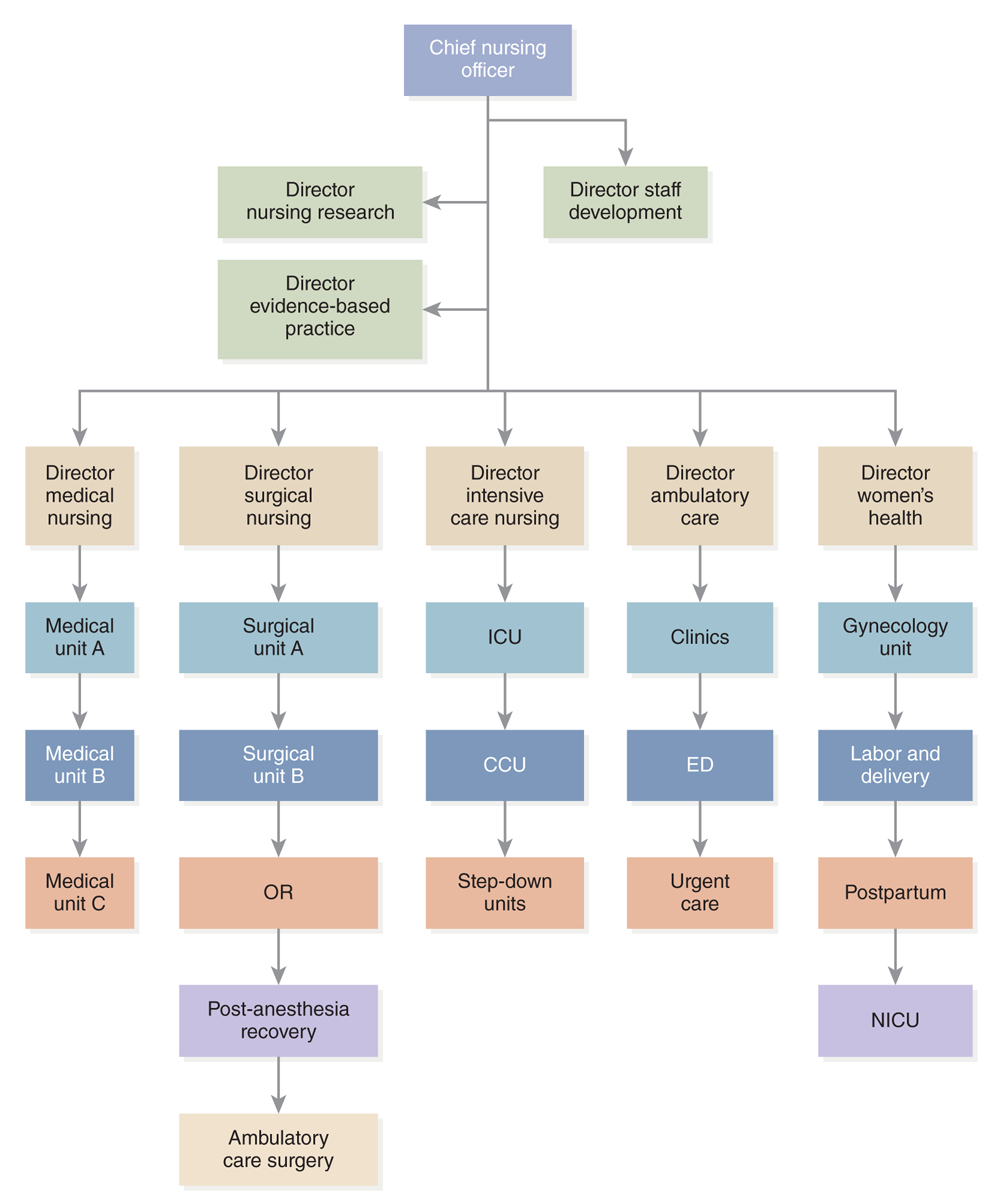

One way to describe a hospital is to consider its structure and process. A hospital's structure is based on an organization's configuration, and the best source for a view of a hospital's structure is its organizational chart. Figure 8-2 provides an example of a hospital organizational chart, which displays a vertical view of hospital components. The chart identifies the staff reporting path, or rather, who is a staff member's manager or supervisor, not by name but by position title. Organizations that focus on this type of structure tend to be more bureaucratic and highly centralized, with key persons in the organization making decisions. Bureaucratic organizations typically have the following characteristics:

Figure 8-2 Example of a hospital organizational chart.

A hierarchical organizational chart depicts the structure of a hospital.

At the top is the Board of Directors, followed by the President and Chief Executive Officer, C E O. Below the C E O is the Senior Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, C O O. Reporting to the C O O are several Vice Presidents: Chief Information Officer, C I O, Quality and Patient Safety, Human Resources, Medical Affairs, Professional Practice and Chief Nursing Officer, C N O, and Chief Financial Officer, C F O.

- Division of labor: descriptions of jobs that include clearly defined tasks

- Defined hierarchy: clear description of reporting relationships

- Detailed rules and regulations: greater emphasis on policies and procedures; expectation that these will be followed and guide decision-making

- Impersonal relationships: expectation that staff will do their jobs, and supervisors will ensure that jobs are done as required

Hospitals typically have hierarchical management levels. The top level consists of the board of trustees or board of directors. The board often includes members of the community and community leaders who are not directly involved in health care. The goal is to have a broad range of input from different stakeholders to assist in developing the overall direction of the hospital and ensure that the goals of the organization and the community are met. The board hires the hospital's chief executive officer (CEO-sometimes called the organization's president), and this person reports to the board. The CEO then hires the other major leaders for the hospital, such as the chief financial officer (CFO) and the nursing leader, who may be called the chief nursing executive (CNE), the chief nursing officer (CNO), or in some cases, the vice president for nursing or patient services. The last title reflects the person's oversight of nursing but may also include other disciplines or ancillary services, such as occupational therapy, physical therapy, or nutrition. Often, the board approves management/leadership hires recommended by the CEO. Because the board has ultimate responsibility for the budget, it has significant influence over matters that impact nurses, such as staffing and other resources important to nursing.

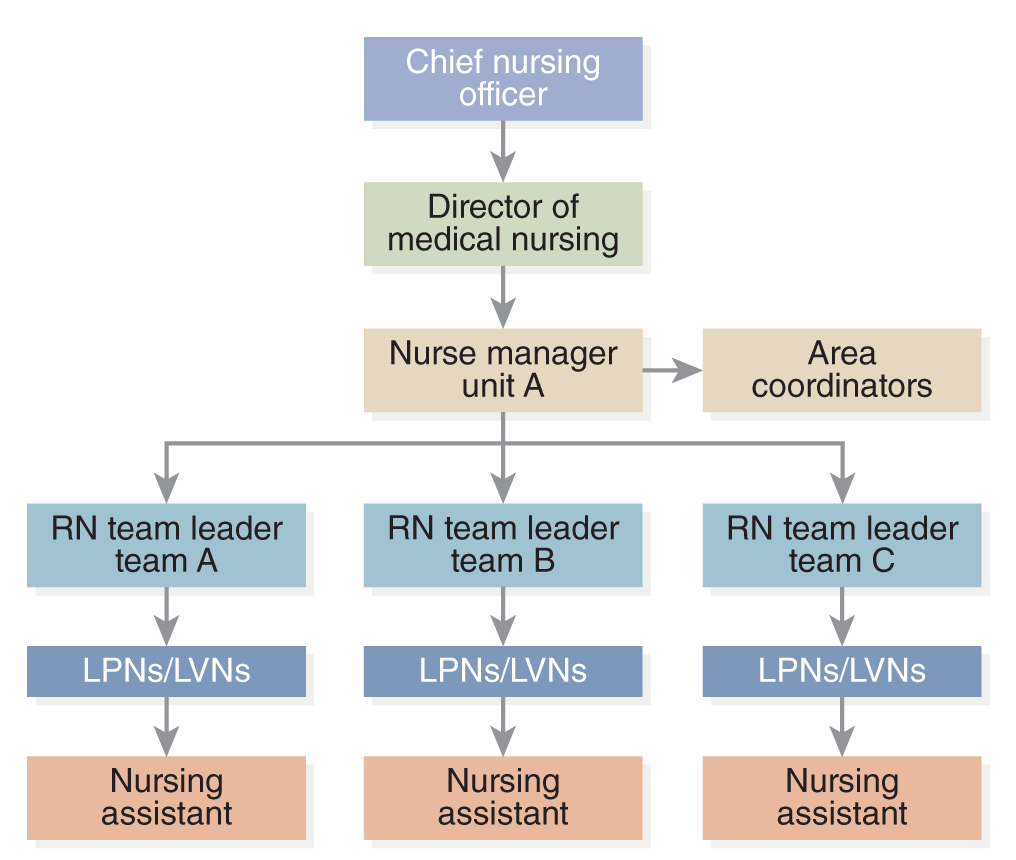

Although bureaucratic organizations are less common today, many hospitals still use this approach, emphasizing a vertical structure that includes these elements, but it is less rigid than the structure of past formal bureaucratic organizations. Line authority, or chain of command, is very important in that each staff member needs to know to whom to report, and it is expected that this order will be followed. A bureaucratic organization may not expect or want much staff input regarding decisions, but today, this model is less common. HCO administrations are now encouraging more staff commitment and, thus, engagement in the organization-greater emphasis on teams and interprofessional collaboration. Another element of organizational structure is the span of control, or the number of staff managed by each supervisor or manager. The more staff a manager supervises, the more complex that supervision becomes.

A horizontal structure is decentralized, with emphasis placed on departments or divisions and decision-making occurring closer to where work is done. Departments or divisions focus on special functions, such as those related to nursing, laboratory, pharmacy, dietary/patient, and medical services. This is referred to as departmentalization. Later in this chapter, examples of common hospital departments or services are discussed.

The matrix organization structure is newer and less clear than the traditional bureaucratic organization that is centered on departments. In a matrix organization, staff might be part of a functional department, such as nursing services, but if the nurse works in surgery, the nurse may also be considered a staff member in the surgical services/department. This type of organization is considered flatter because decisions do not flow clearly from the top down but focus more on the service or department, though there still must be consideration of the overall organization structure and functions.

Process, the other dimension of organizations, focuses on how the organization functions. How would a staff member gain an understanding of a hospital's process? The hospital's vision, mission statement, and goals are a good place to begin to find out what is important to the organization and how the hospital describes itself and its functions. Other sources of information relevant to the process include policies and procedures, communication systems and expectations, decision-making processes, delegation processes, implementation of coordination (teams), informatics, and evaluation methods (quality improvement [QI]). The key question is: How does the work get done?

Classification of Hospitals

Hospitals can be classified using a variety of descriptors. The following are some of these descriptors:

- Ownership: Is the hospital for-profit (investor owned), not-for-profit, part of a corporate system, faith based, or governmental (county, state, federal)? Government hospitals include Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals, military hospitals, state mental health hospitals, the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and Indian Health Service hospitals.

- Number of beds: Bed size or the number of beds can vary widely from hospital to hospital.

- Licensure: State health departments are responsible for hospital licensure, which ensures hospitals in the state meet state standards. Licensure and accreditation are not the same, though they are both concerned with quality. Licensure is based on government policies and government agencies that implement licensure requirements. Accreditation is a process to determine whether a hospital meets certain minimal standards; this process is voluntary and provided by a nongovernmental organization. For hospitals to receive Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement, an important source of income for hospitals, they must be certified or given authority by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to provide services to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries and request CMS reimbursement. Meeting all these requirements and participating in the evaluation surveys take staff time, which is costly, but it is very important for the overall financial status of an HCO. In addition, hospitals that do not meet these requirements cannot be used as sites for healthcare professional student clinical practice experiences (nursing, medicine, and others). Professional provider licensure and related regulations are discussed in other chapters.

- Teaching: A hospital is classified as a teaching hospital if it offers residency programs for physicians. The expansion of nurse residency programs may also become a method for classifying hospitals in the future, although this is not done at this time, and few hospitals have such programs. Some hospitals are referred to as academic health centers (AHCs). These hospitals are associated with academic institutions that offer healthcare profession education, primarily medicine, but typically, if the university has a nursing program or other programs, such as pharmacy, they will also be associated with the AHC. In these hospitals, there may be cross-administration-for example, the dean of medicine and dean of nursing may have positions in the hospital as well as some of the faculty. This is a more formal arrangement than referring to a hospital as a teaching hospital where students have clinical experience based on curriculum needs.

- Multihospital system: Since 1991, hospital systems that include multiple hospitals have increased in number of systems and in bed size. These systems often provide more than just acute care services; for example, they may offer ambulatory care (clinics, surgery), hospice care, home health care, long-term care, and other services. The newest service that is expanding is digital health (telehealth, telemedicine). This partnering provides the hospitals with a continuum of services, from acute care to long-term care, to meet the needs of their patients. In a sense, the system does not lose the patient when the patient is transferred to a different part of the system for additional care needs, and if needs change, the patient may return to different parts of the system for other services. For example, a patient has been in a hospital intensive care unit for complications related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder. The patient returns home after discharge and receives home health care from the hospital's home healthcare agency and may use digital health services. One week after discharge, the home healthcare nurse assesses the patient and decides the patient may need to be rehospitalized because of pneumonia and refers the patient to the physician. The patient is then admitted to the same hospital where earlier care was received.

- Length of stay: Length of stay refers to how long patients typically stay in a hospital, a measure given as a range or average length of stay. Fewer than 25 days is referred to as short-term acute care, and more than 25 days is long term, such as for rehabilitation. Length of stay has decreased because of decreasing reimbursement for hospital care and a greater push to provide more healthcare services outside the hospital. The average length of stay (ALOS) is important data for acute care hospitals that describes the average number of days a patient stays in the hospital. Delays in discharge, however, have increased from 2019 to 2022 by about one-fifth (19%), and when due to inadequate access to appropriate posthospital care by 24% (Lagasse, 2022). This not only has a negative impact on hospitals that might not receive appropriate reimbursement for these extra days while patients wait for additional posthospital care but also on patient outcomes and lengthens recovery periods. Indicating the complexity of responding to LOS, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) notes the following: “Few studies have evaluated system-level interventions focused on medically complex, high-risk, or vulnerable patient populations, including frail elderly patients and those with complex chronic illness. Strategies assessed in multiple systematic reviews include geriatric consultation services and early specialized discharge planning” (HHS, AHRQ, 2022). Patient populations with issues related to the social determinants of health (SDOH) and complex medical problems are at higher risk for unnecessary discharge delays and may experience adverse events during and after hospitalization. This requires a hospital-based plan to apply interventions to reduce LOS. Examples of effective organizational interventions within hospitals or health systems to address LOS are discharge planning, geriatric assessment or consultation, medication management, clinical pathways, inter- or multidisciplinary care, case management, hospitalist services, and telehealth.

Typical Departments in a Hospital

As was discussed in relation to the structure of organizations, hospitals have departments, divisions, and/or services. This structure has existed for a long time. Students need to be familiar with these departments because nurses interact with most of them at some point in their practice, and they need to know how to coordinate care by using services from a variety of departments and collaborating with interprofessional staff. What are some of the departments found in an acute care hospital? Titles may vary from hospital to hospital, but the functions described here are typical and part of daily hospital operations.

- Administration: This is the leadership for the hospital, the central decision-making source-for example, the CEO or administrator; assistant administrators; financial services and budget staff; the CNO, CNE, or vice president for nursing or patient services; department heads; and others.

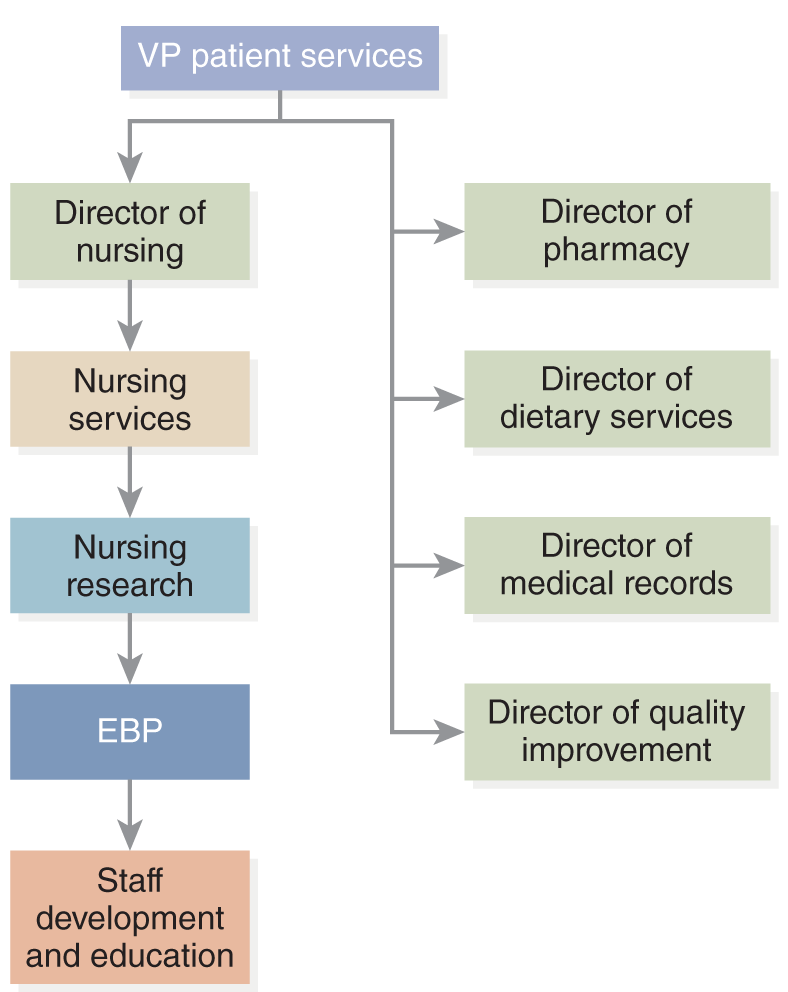

- Nursing: This is the largest department in terms of employee numbers. Often, it is called “patient services,” which is the title used by many hospitals since the early 1990s. This does not mean that patients receive only nursing care; many other departments are directly involved in patient care, such as laboratory, dietetic services, respiratory services, pharmacy, physical therapy, social services, and others. However, nursing service is the 24/7 coordinator of patient care and provides the largest percentage of direct care to patients.

- Medical staff: Physicians who practice in a hospital, if not part of a training program, such as a residency or fellowship, must be members of the medical staff. Their credentials are reviewed, and they are given admitting privileges. This is done to ensure that medical profession standards are met. A director or chief of medical staff leads the medical staff. Some medical staff may or may not be employees of the hospital; for example, medical school faculty may be given privileges to practice in the hospital but not paid by the hospital as employees but paid by the medical school. If a college of medicine is partnered with the hospital, the organization may be more complex, as noted earlier with AHCs.

- Admission and discharge: This department manages all aspects of patient admission and discharge, including paperwork, reimbursement, patient room assignments, and, in some cases, physician assignments. Case management may be part of this department or part of patient services.

- Social services: Professional staff that assist patients and families with social services based on patient needs in the hospital or postdischarge.

- Medical records: Documentation is critical to all aspects of care. The medical records department provides oversight of documentation, whether paper or information in a computerized system, ensuring that policies and procedures are followed. This complex function requires nursing input to ensure that nursing documentation is recognized and nursing care information is included. These records are also used for quality improvement efforts and are needed to support requests for reimbursement for services.

- Information management: This department ensures that required information is collected, analyzed, monitored, and summarized-typically administrative and clinical data. Its function is directly related to medical records and documentation. Another area in which information management is important today is for quality improvement efforts. Staff also need ongoing training to ensure the effective use of digital information systems (e.g., electronic medical/health records). Health information technology (HIT) is a rapidly expanding area in healthcare organizations.

- Quality improvement: This department is charged with ensuring that the hospital has a QI program, implements active continuous QI efforts, evaluates its outcomes, and makes changes to improve care. Nurses are often part of the staff in this department because their experience and knowledge can be helpful in providing and assessing quality care. In general, all nurses should be actively involved in these activities throughout the hospital and in their daily practice. Additional discussion on QI is found in other chapters.

- Infection control: This function has become increasingly important, influenced by a greater need to provide services that decrease infection risk for patients and staff. Nurses are typically active staff members in this department, developing and implementing policies and procedures, monitoring infection rates, and training staff.

- Research and evidence-based practice (EBP): Many hospitals, particularly AHCs, have research departments. The department's purpose is to conduct research studies and review and approve studies prior to their implementation through the HCO's institutional review board (IRB). Typically, professionals in medicine lead this department, although nurses often participate in research and may direct their own nursing studies. The nursing department may have its own designated nurse researchers. In some HCOs, research and EBP are combined, or there may be a separate EBP service or department. The EBP department is one of the newest in hospitals, and not all hospitals have this department. Some hospitals incorporate EBP management-both medicine and nursing EBP-into other departments; for example, the EBP functions may be part of nursing or patient services, QI, or evidence-based medicine associated with the medical staff organization. Additional information on research and EBP is found in other chapters.

- Staff/professional development/education: This is the department that provides staff orientation and ongoing staff education.

- Environmental services (housekeeping): Staff from this department interact with nurses in the patient care areas to ensure that areas are clean and safe for patients.

- Dietary/nutrition: This department is responsible for ensuring patient nutritional needs are met through meals that conform to individual patient dietary requirements and offer other dietary interventions.

Other departments focus on specific health needs, such as pharmacy, respiratory therapy, clinical laboratory, infusion therapy, occupational therapy, radiology, and Physical therapy. Nurses are involved in all these services. Hospitals are typically organized around clinical areas (units, services, and, in some cases, departments), such as medicine, surgery, intensive care (medical intensive care unit [MICU], surgical intensive care unit [SICU], cardiac care unit [CCU], and neonatal intensive care unit [NICU]), postanesthesia unit (PACU), labor and delivery (L&D), postpartum, nursery, gynecology, pediatrics, emergency department (ED), urgent care, psychiatric or behavioral/mental health, ambulatory care, ambulatory care surgery, and dialysis. Clinical areas may also focus on a specialty, such as medical units for the postcardiac care unit, which may be referred to as step-down units, oncology units, or other internal medicine subspecialties; surgical units might focus on orthopedics, urology, and so on.

Patient Flow

The right care in the right place and at the right time can sometimes be a challenge both for patients and for healthcare providers and HCOs (Rutherford, 2020). Healthcare systems are complex and difficult to manage. Over the years, there has been increased concern about patient flow-patients not moving from one area of care to another when they need to be moved or may not be in the best healthcare service area for their care needs. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this long-term problem, increasing the number of patients waiting for services in emergency departments and even in ambulances or having no contact with needed services (Rutherford, 2020). Mental health services have had patient flow problems with barriers to providing effective and efficient ambulatory care, inpatient care, long-term care, and care in the home. Hospital-wide patient flow needs to be addressed, as it impacts nurses and their practice. Services are interdependent but are not always aware of each other and what needs to be done to increase effective patient flow. This impacts the system's communication, coordination, staffing, staff stress, patient transportation, supplies and pharmaceutical needs, workload, patient reimbursement, admissions and discharges, and budget. Understanding the problem is the first step-what interferes with patient flow? Staff need to develop methods to resolve the problems, and this requires staff communication and collaboration. Patients and families should be asked about these issues-they may have suggestions that would improve patient flow.

| Stop and Consider 2 |

|---|

| Organizational structure and process affect healthcare organizations. |

Healthcare Providers: Who Is on the Team?

The hospital healthcare team providing care is composed of a variety of healthcare providers, both professional and nonprofessional. All are important in the care process. In addition, many other staff are critical to the overall operation of a hospital, such as staff associated with office support, dietary, housekeeping, facilities management and maintenance, patient transportation, medical records, communications (HIT), equipment maintenance and repair, security, and many others. For our purposes in this text, the focus is on staff that provide care, either direct or indirect patient care. A staff member who provides direct care, such as a nurse, is in contact with the patient, referred to as a direct care provider. An indirect care provider might be someone who works in the lab to complete a lab test but may never actually see the patient; however, the work done in the lab is very important to patient care.

The group of staff who provide care to a patient is referred to as a team. They have a common purpose: providing patient care. Interprofessional teamwork is one of the recommended competencies for all healthcare professionals and is discussed in other chapters. Nurses work together with other nursing staff (licensed vocational nurses [LVNs] or licensed practical nurses [LPNs] and nursing/patient care assistants) to provide care. Today, there is also greater emphasis on the need for interprofessional teams in which nurses collaborate and coordinate with members of multiple disciplines, such as physicians, pharmacists, physical therapists, social workers, and many other members.

The following are examples of some of the major team members and their functions. Not all patients require services from all these healthcare professionals; PCC services are based on individual patient needs.

- Registered nurse (RN): Nurses are the backbone of any acute care hospital. They work in a variety of positions and departments, not just the nursing department; for example, they work in medical records, QI, infusion therapy, case management, staff/professional development, radiology, ambulatory care, and other departments. Some nurses are in management positions and do not provide direct care.

- Licensed practical/vocational nurse (LPN/LVN): An LPN/LVN is a nursing staff member who has completed a minimum one-year nursing program, successfully passed the LPN/LVN licensing exam, and is licensed by the State Board of Nursing in which they practice. They are supervised by RNs and are important team members. The State Board of Nursing determines what care they may provide, although not all states use the LPN/LVN designations. It is important for RNs to know what LPNs/LVNs are allowed to do, requiring familiarity with their position descriptions and providing supervision for this care. RNs can delegate to LPNs/LVNs based on state guidelines, but the reverse is not true.

- Patient care assistant or nursing assistant: Patient care assistants or certified nursing assistants may have a variety of titles. They are nonprofessional nursing staff who have a short training period (typically a few months) that prepares them to provide direct care, such as assisting with activities of daily living (bathing, taking vital signs, helping with meals, mobility, and so on). They are supervised by RNs or, in some cases, by LPNs/LVNs and are important members of the team.

- Advanced practice registered nurse (APRN): A nurse practitioner is an RN with a master's degree in a specialty, although this requirement is changing to a doctor of nursing practice (DNP) (see content on nursing education in Chapter 4). In some states, APRNs may provide some services independent of physician orders, such as prescribing certain medications and treatment procedures. APRNs may work in ambulatory care settings, clinics, schools, and so on and, typically, do not work in acute care hospital units, although this varies. In some states, APRNs may have admitting privileges along with their prescriptive authority (the right to prescribe medication).

- Clinical nurse specialist (CNS): A CNS is an RN with a master's degree. This nurse is prepared to provide care in acute care settings and guides the care provided by other RNs. Examples of CNS specialties are cardiac care and behavioral health (psychiatry/mental health), where they work with staff to improve care, assist in educating staff, and focus more on EBP.

- Clinical nurse leader (CNL): This nurse has a master's degree and is a provider and a manager of care at the point of care to individuals and cohorts (groups of patients). This is not in an administrative or manager position. The CNL may be involved in team leadership by improving information management to ensure quality care; determining patient risk and addressing it with interventions; collecting outcome data for quality improvement; applying EBP; advocating for patients, the community, and the care team; and providing other related activities (AACN, 2023). Overall, the CNL is involved in care planning, coordination, and working with the nursing and interprofessional teams to better ensure quality care and outcomes.

- Certified nurse-midwife (CNM): A nurse-midwife has a master's degree and is prepared to provide women's health services and services to obstetric patients (labor and delivery, postpartum, and obstetric clinics). In some states, CNMs have admitting privileges. Their scope of practice may be regulated under either the medical or nursing practice act, depending on the state. Some CNMs are completing DNP requirements.

- Certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA): The nurse anesthetist has, until recently, completed a master's degree, but as discussed in other chapters, the degree requirement for CRNAs is transitioning to a DNP degree rather than a master's degree (as of 2025). The CRNA is prepared to provide services to patients requiring surgical anesthesia in hospitals, ambulatory care surgery, and procedures that require anesthesia.

- Doctor of nursing practice (DNP): An RN with a DNP has a terminal doctor of practice degree and is prepared to carry out roles similar to the traditional APRN in addition to focusing on EBP at the system level of care, quality improvement, leadership, and healthcare financial issues. These nurses may hold a variety of positions in a hospital. The impact of the DNP is still being examined, but the degree holds promise for “innovation around new care delivery models, interdisciplinary projects, and community involvement for a healthier society” (Tussing et al., 2018, p. 602).

- Physician: A physician has a medical degree and is typically in a specialty, such as surgery, medicine, pediatrics, or obstetrics and gynecology. Some physicians may even have a subspecialty; for example, a physician with a specialty in internal medicine may subspecialize in rheumatology, dermatology, oncology, or neurology. A surgeon may subspecialize in orthopedics, oncology (and even more specifically in breast surgery), and so on. In a teaching hospital, which has medical students and residents, and in AHCs, the typical team includes faculty/attending physicians, the chief resident, residents, and medical students. They are responsible for the medical aspects of patient care and have oversight of overall care requirements.

- Physician's assistant (PA): A PA is prepared to practice some aspects of medicine under the supervision of a physician. The PA conducts physical examinations, performs diagnostic workups, makes diagnoses, prevents and treats diseases, assists with procedures, and may have some prescription privileges.

- Pharmacist: The pharmacist has completed professional specialty education and ensures that pharmaceutical care is appropriate for patient needs. Given the growing concern about medication errors, pharmacists are important members of the team, and nurses should work closely with them. Some hospitals have a centralized pharmacy department, and all pharmaceutical services come from the central unit. Others have moved to include pharmacists as direct team members on several units, providing an invaluable service and staff education from the pharmaceutical staff at the point of care. In some communities, pharmacists provided important services during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as patient information, testing for the virus, vaccines, and treatment prescriptions. They routinely provide important public/community health services.

- Occupational therapist (OT): OTs are not present in every hospital, but they provide important services for patients with rehabilitation needs because of impaired functioning, such as patients who have had a stroke or experienced a serious automobile accident. Another type of therapist that might be used for patients who have had a stroke is a speech-language pathologist. These types of therapists are commonly found in rehabilitation services, but their services can also be provided in all types of settings, such as in hospitals, long-term care facilities, home health care, and clinics.

- Physical therapist (PT): PTs provide musculoskeletal care to patients, such as teaching patients how to walk (e.g., stroke or post-hip replacement patients) or use crutches or other assistive devices. They also help design exercises to ensure or increase patient mobility and may train nurses to assist in providing physical therapy for patients as they provide daily patient care. These services can also be provided in all types of settings, such as in hospitals, long-term care facilities, home health care, and clinics.

- Registered dietitian: Dietitians work with patients to help resolve dietary and nutritional needs. Nurses work with dietitians as patients' dietary needs are identified and implemented.

- Respiratory therapist: Respiratory therapists provide care to patients who have a variety of respiratory problems. They are trained to provide specific types of treatments, such as oxygen therapy, inhalation therapy, intermittent positive-pressure ventilators, and artificial mechanical ventilators. Respiratory therapists go to the patient's bedside to provide these treatments. Some respiratory therapists may be assigned to work solely in intensive care units, where there is a great need for these treatments. Respiratory therapists are also part of the team that responds to codes when patients experience critical cardiac or respiratory changes.

- Social worker: Social workers have professional degrees and assist patients and their families with issues such as reimbursement, discharge concerns, housing, transportation, discharge plans, and other social services. They are concerned with SDOH. Nurses work with social workers to identify patient issues that need to be resolved to decrease stress on patients and families. Social workers (and nurses) may serve as case managers, and they may be important resources in providing effective discharge plans and follow-up care.

Medical care in acute care has been examined over the last few years, identifying several problem areas that have led to changes in some hospitals. Two of the newest members of the healthcare team are the hospitalist and the intensivist. The hospitalist position is usually filled by a doctor of medicine (MD), although APRNs may hold this position in some hospitals (Carlson, 2020). The hospitalist is a generalist who coordinates the patient's care, serving as the primary provider while the patient is in the hospital. In this case, the patient's primary care provider outside the hospital is not involved in the patient's inpatient care, and the patient returns to that provider in the community after discharge. This reduces the time that the primary care provider (internist, family practitioner, pediatrician) needs to devote to inpatient care. Thus, the primary care provider (PCP) has more time to focus on the patient's outpatient needs. In addition, the hospitalist is more current with acute care and the treatment required. The intensivist is similar to the hospitalist, but because this MD focuses on patient care in intensive care, this is more specialized patient care and requires physicians who are up to date on critical information and intensive care procedures. The hospitalist and intensivist positions were developed to increase coordination and continuity of care in the hospital. Both providers are paid hospital employees. A major disadvantage of this medical care model is that the patient has no relationship with the hospitalist or the intensivist prior to hospitalization and will not have any contact after hospitalization, which may not be acceptable to some patients. If APRNs are in this role, this, too, may not be acceptable to some patients. Patient choice is always an important factor to consider as this has a direct impact on patient satisfaction and patient engagement in the care process and on outcomes.

| Stop and Consider 3 |

|---|

| Nurses need to understand the roles of multiple healthcare providers. |

Healthcare Financial Issues

Healthcare financial issues can be viewed from three perspectives. The first perspective is the macro view, or the status of healthcare finances viewed from a national or a state perspective. The second is the micro view, which focuses on a specific HCO and its budget. A third perspective is reimbursement for individual healthcare organization services.

The Nation's Health Care: Financial Status (Macro View)

The macro view is important because it encompasses the major financial support for the U.S. healthcare system. The United States spends a lot of money on health care, yet not everyone is covered by healthcare insurance. As is true for the reporting of most government data, national health expenditures (NHE) data are behind the current year. The data for 2018 indicated the following (HHS, CMS, 2021):

- NHE grew 2.7% to $4.3 trillion in 2021, or $12,914 per person, and accounted for 18.3% of gross domestic product (GDP).

- Medicare spending grew 8.4% to $900.8 billion in 2021, or 21% of total NHE.

- Medicaid spending grew 9.2% to $734.0 billion in 2021, or 17% of total NHE.

- Private health insurance spending grew 5.8% to $1,211.4 billion in 2021, or 28% of total NHE.

- Out-of-pocket spending grew 2.8% to $375.6 billion in 2018, or 10% of total NHE.

- Other third-party payers and programs and public health activity spending declined 20.7% in 2021 to $596.6 billion, or 14% of total NHE.

- Hospital expenditures grew 10.4% to $433.2 billion in 2021, 10% of the total NHE.

- Physician and clinical services expenditures grew 5.6% to $864.6 billion in 2021, a slower growth than the 6.6% in 2020.

- Prescription drug spending increased by 7.8% to $378.0 billion in 2021, faster than the 3.8% growth in 2020.

- The federal government (34%) and households (27%) sponsored the largest shares of total health spending. The private business share of health spending accounted for 19.9% of total healthcare spending, state and local governments accounted for 17%, and other private revenues accounted for 7%.

To plan for future healthcare needs, the government also projects NHE, as noted in the following for 2019-2028:

- National health spending is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 5.4% for 2019-2028 and to reach $6.2 trillion by 2028.

- Because national health expenditures are projected to grow 1.1 percentage points faster than GDP per year on average over 2019-2028, the health share of the economy is projected to rise from 17.7% in 2018 to 19.7% in 2028.

- Price growth for medical goods and services (as measured by the personal healthcare deflator) is projected to accelerate, averaging 2.4% per year for 2019-2028, partly reflecting faster-than-expected growth in health sector wages.

- Among major payers, Medicare is expected to experience the fastest spending growth (7.6% per year over 2019-2028), largely because of having the highest projected enrollment growth.

- The insured share of the population is expected to fall from 90.6% in 2018 to 89.4% by 2028.

It is important to note that this projection does not fully consider the financial impact of COVID-19 on healthcare expenditures. It is recognized that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a major impact on individuals and their ability to cover healthcare costs, healthcare providers (individuals and healthcare organizations, health insurance), and government budgets (local, state, federal)-short-term and long-term impact.

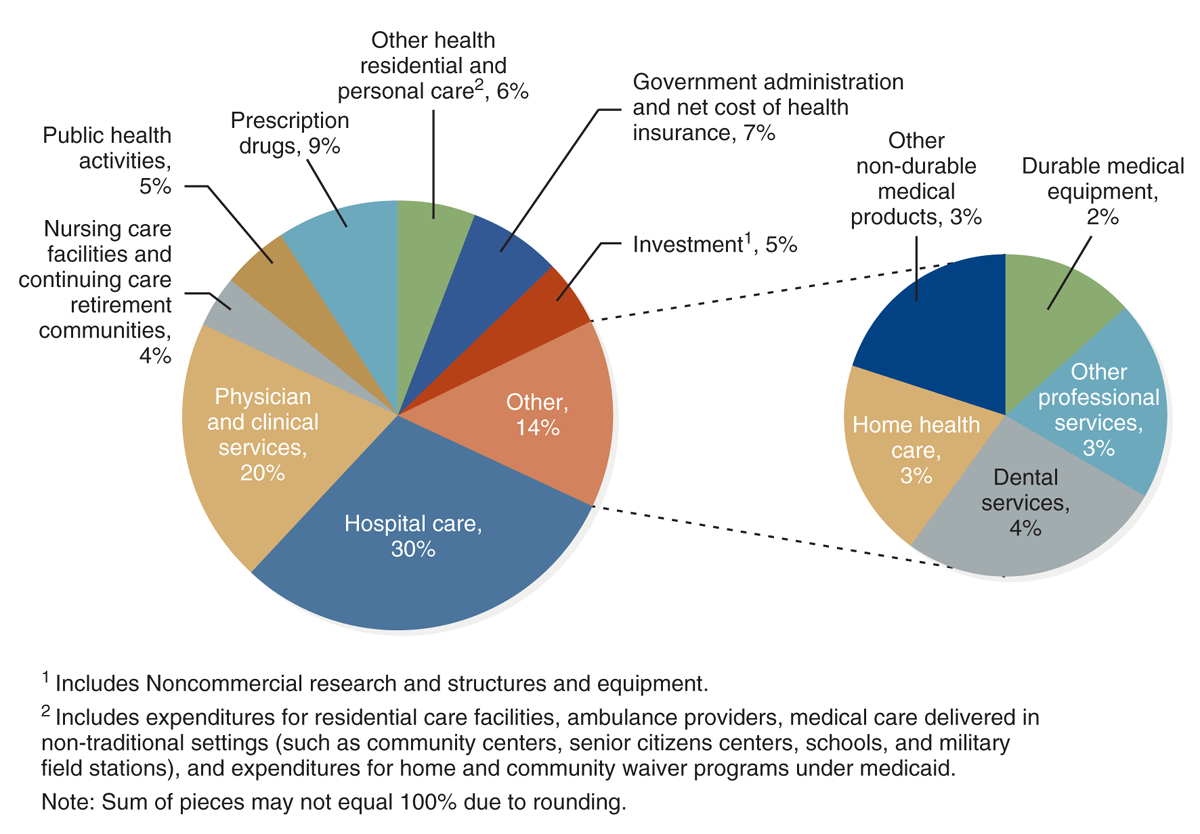

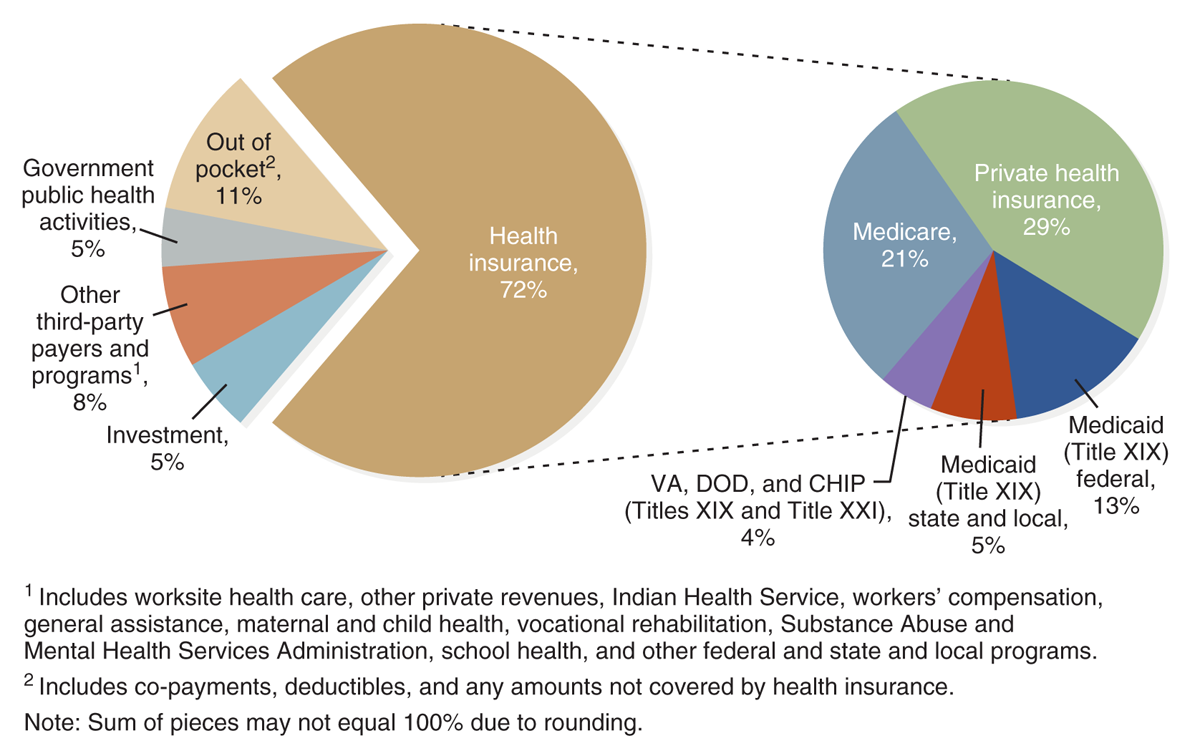

Reimbursement issues impact the status of health care and coverage of these expenses. Figure 8-3 describes the nation's healthcare dollar, describing CMS reimbursement as it is the major payer at the federal level-how much Medicare and Medicaid spent on different categories of services and Figure 8-4 describes CMS payments for services. These expenditures are changing, and they are increasing.

Figure 8-3 The nation's health dollar, calendar year 2021, where it went.

Two pie charts depict the distribution of the nation's health spending in 2022.

The left pie chart depicts overall spending: Hospital Care: 30 percent. Physician and Clinical Services: 20 percent. Prescription Drugs: 9 percent. Government Administration and Net cost of Health Insurance: 7 percent. Other Health Residential and Personal Care, superscript 2: 6 percent. Investment, superscript 1: 5 percent, Public Health Activities: 5 percent. Nursing Care Facilities and Continuing Care Retirement Communities: 4 percent. Other: 14 percent. The right pie chart breaks down Dental Services: 4 percent. Other: Home Health Care: 3 percent. Other Professional Services: 3 percent. Other Non-Durable Medical Products: 3 percent. Durable Medical Equipment: 2 percent. Text for superscript 1 reads, Includes non-commercial research and structures and equipment. Includes expenditures for residential care facilities, ambulance providers, medical care delivered in non-traditional settings, such as community centers, senior citizens centers, schools, and military field stations, and expenditures for Home and Community Waiver programs under Medicaid. Sum of pieces may not equal 100 percent due to rounding. Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group (NHS). (2021). https://www.cms.gov/files/document/nations-health-dollar-where-it-came-where-it-went.pdf

Figure 8-4 Medicare benefit payments by type of service.

Two pie charts illustrate the sources of the 4.5 trillion dollars for the health sector for the calendar year 2022.

The left pie chart depicts the overall distribution: Health Insurance: 72 percent. Out of Pocket, superscript 2: 11 percent. Other Third Party Payers and Programs, superscript 1: 8 percent. Investment: 5 percent. Government Public Health Activities: 5 percent. The right pie chart breaks down Health Insurance: Private Health Insurance is 29 percent, Medicare 21 percent, Medicaid, Federal, 13 percent, Medicaid, State and Local, 5 percent, and V A, D O D, and CHIP 4 percent. Text for superscript 1 reads, Includes worksite health care, other private revenues, Indian Health Service, workers' compensation, general assistance, maternal and child health, vocational rehabilitation, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, school health, and other federal and state and local programs. Superscript 2 reads, includes co-payments, deductibles, and any amounts not covered by health insurance. Note: Sum of pieces may not equal 100 percent due to rounding. Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group (NHS). (2021). https://www.cms.gov/files/document/nations-health-dollar-where-it-came-where-it-went.pdf

The Individual Healthcare Organization and Its Financial Needs (Micro View)

The hospital budget is used by hospitals to manage their financial issues-to plan, monitor expenses and revenue, and then adjust to ensure financial stability. The budget is prepared for a specific period, usually a year. In addition, a longer-term strategic plan, covering several years is prepared, although this plan must be adjusted over time because of changes in the HCO's financial status and other factors that affect the HCO and its services. The budget describes expected expenses, such as staff salaries and benefits, equipment, supplies, utilities, pharmaceutical needs, facility maintenance, dietary needs, administrative services, clinical care, HIT, QI, staff education, legal fees, the HCO's insurance coverage, parking and security, and so on, and includes any major expenses outside of operating expenses, such as expansion or renovation. This budget also includes projected revenue or money coming into the organization.

It is very important for nursing management to participate in the budget process because the budget has a major impact on nurses and nursing care. Reimbursement and other aspects of healthcare finance affect nursing care and relate to the following questions:

- Are there enough nursing staff to meet needs? Impact on pay and staff benefits?

- Are there sufficient and effective support services for nurses so that they are free to provide care rather than spend time on nonpatient duties?

- Are the most up-to-date supplies and equipment available? (For example, as we experienced with COVID-19, having PPE for staff is critical as well as enough respirators for patients.)

- Is there an efficient computerized documentation system?

- Is orientation sufficient for new staff?

- Does the nursing staff receive the ongoing training it needs?

- Are nurse managers provided with effective training and education?

All of these are critical questions and of interest to nursing staff. Nursing leaders in an organization should be actively involved in cost-containment decisions because these decisions affect answers to these questions. Nurses should also work collaboratively with interprofessional leaders and staff recognizing that financial decisions are not limited to one specific profession or service. This, however, requires that nurses understand and consider financial issues objectively. More content on health economics is needed in nursing education programs to develop competencies not only for graduate students but also for prelicensure students (Platt et al., 2015). The AACN Essentials include recognition of the need for baccalaureate degree programs to incorporate knowledge of financial and payment models offering content on reimbursement and healthcare costs in the domain focused on systems-based practice (AACN, 2021). Nurse managers and administrators have the most responsibility for financial decisions; however, for staff nurses to actively engage and be effective in the organization, they, too, need to have some understanding of this area and provide input when needed. Nurses are not usually directly involved in the development of budgets unless they are in a management position; however, it is important for nurses to understand what a budget is and why it is important. Nurse managers need to ask their nursing staff for input when unit budgets are developed and then share budget outcomes with staff, asking for suggestions when there is need to resolve budget issues. The nursing department administrator should consult with department nurse managers as budgets are developed and monitored.

The hospital board of directors approves the final HCO budget, which combines budgets from the HCO units, departments, and other components. After a budget is approved and implemented, it is important that budgetary data are monitored on a regular basis, and this information should be shared with the organization's managers throughout the year. This monitoring is done to better ensure that budget goals are met and facilitate early recognition of budget issues that may require adjustment in the budget and in the workplace.

Reimbursement: Who Pays for Health Care?

Reimbursement is a critical, complex topic in health care. It represents the third perspective on healthcare financial issues. Nursing students may wonder why this topic is relevant to them or even to nurses in general. Basically, reimbursement pays the patient's bill for services provided, and this payment, in turn, covers the costs of care, such as staff salaries and benefits, drugs, medical supplies, physician fees, facility maintenance and upgrades, equipment, general supplies, and much more. These monies then provide healthcare providers with funds to pay their own bills and cover their services. So, for example, reimbursement dollars eventually become the dollars that pay staff salaries and benefits in hospitals, clinics, physician practices, home healthcare agencies, and so on.

Hospitals that do not have enough income to pay their bills are said to be operating in the red, and this is not a good position for a hospital. Many hospitals experience this problem, but how far in the red can make the difference between modernizing or filling staff positions or not doing so-even if the hospital stays open for business. Some hospitals in this country have closed, and the United States also experienced closings because of COVID-19. This may have been due to a combination of long-term financial weakness and then the pandemic exacerbated the financial problems (Stuart, 2020). Particularly hard hit are hospitals in rural areas and small hospitals that are not able to compete for patients. Their closing may have a major impact on access to care in some communities resulting in some patients not having access to a local hospital for needed services or even for emergency services. In some communities where local small hospitals may have limited services, people may have to travel long distances for services such as obstetric care or specialized care for children (pediatrics, neonatal care for newborns), mental health services, oncology (diagnosis and treatment), complex surgical procedures, and other specialized services.

The United States is experiencing a crisis in its safety net hospitals. The government defines safety net hospitals as hospitals that provide a significant amount of care to vulnerable populations, Medicaid patients, and the uninsured (HHS, AHRQ, 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was even greater need for this support to vulnerable populations (Pugh, 2020; Morse, 2020). Often, these hospitals are teaching hospitals and AHCs. This does not mean these hospitals do not or could not serve patients with sufficient reimbursement; however, it is typically the case that many of their patients cannot meet reimbursement requirements for services. In some cases, potential patients with insurance do not want to go to these hospitals, reducing access to effective reimbursement funds. Patients with limited or no reimbursement also tend to have more complex care needs due to several factors, such as low income, medical vulnerability, complex social needs, limited preventive care, and many experience other SDOH, as discussed in other chapters. Some of these patients have chronic medical conditions that have not been adequately treated. Other complications include socioeconomic problems, language issues impacting health literacy, and immigrant status that may impact access to services and finances, all of which contribute to the need for complex healthcare treatment and support. The safety net hospital system struggles to operate effectively to meet the complex medical and social services for vulnerable populations, but they need sufficient reimbursement for services to cover their operating costs. These systems require changes to meet the needs of often complex patients, provide quality care, and remain financially stable (Dickson et al., 2022)

It is important for nurses to understand basic information about reimbursement. Patients today frequently worry about payment for care. Questions that arise are: Do patients have insurance coverage? How much of their care will be covered by insurance and how much of it will be out-of-pocket that they must pay? Will they get the treatment they need from the providers they prefer? Experiencing an illness is difficult for any patient and the patient's family, and to add worry about payment for services increases stress and can have an impact on a patient's health as well as the patient's response to the health problem and outcomes. This stress can affect whether patients can follow treatment recommendations. Can the patient afford needed medications, or do the costs compromise the patient's ability to buy food or pay rent? Can the patient afford to take a bus or taxi to a doctor's appointment? Can the patient afford to take time off from work for an appointment? None of this is simple, and these factors have a major impact on health outcomes.

The Third-Party Payer System

The U.S. healthcare delivery system is mostly funded through a third-party payer system (insurance) that is primarily employer based, with healthcare services paid by someone other (insurer) than the patient and services provided mostly in private sector HCOs, but also in some public or government HCOs. This means if your employer does not offer an insurance benefit, you must purchase your own insurance, apply for Medicaid or Medicare if you are eligible, or go without insurance. Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), this has become more complicated, and it is a law that continues to experience conflict about its provisions and changes. Examples of private third-party payers are UnitedHealth Group, Humana, and others. Medicare and Medicaid are government programs but also third-party payers, but they are not employers. With third-party payers, the patient pays for part of the care, but the payment for most patient care goes through another party, the insurer (the third-party payer). Typically, the patient or enrollee in the insurance policy is covered as part of a group, most likely through the enrollee's employer healthcare policies and offered as an employee benefit. Some employers allow employees to choose from several policy plan options of varying cost with identified covered services.

Fee-for-service is the most common reimbursement model in the United States. In this model, physicians or other providers, such as hospitals, bill separately for each patient encounter or service that they provide rather than receiving a salary or a set payment per patient enrolled. The third-party payer pays the bills, but the enrollee usually has some payment responsibilities that vary from one policy to another. This is a complex area, and nurses, as consumers of health care and as healthcare providers, need to understand the basics. Enrollees (patients) may pay any or all of the following:

- Deductible: The deductible is the part of the bill that the patient must pay before the insurer pays the bill for services. If the patient reaches the total amount of the deductible allowed per year, the patient pays no additional deductible for that year.

- Copayment and coinsurance: The copayment is the fixed amount that a patient may be required to pay per service (physician visit, lab test, prescription, and so on), and this amount can vary among insurance policies. For example, for a physician visit, the patient may pay a small amount at the time of the visit or be billed by the physician for this patient fee. The insurer pays the rest of the bill at the request of the provider.

Both the deductible and the copayment represent the patient's annual out-of-pocket expenses, in addition to the annual fee or premium that the employee pays for the coverage. These expenses have been steadily increasing for consumers, some years more than others, and these costs are expected to increase. Employers also pay a portion of the annual insurance fee. Fees vary from policy to policy and from one employer to another. There is no requirement in the United States that every employer provide healthcare insurance coverage-there is also no universal healthcare coverage in the United States. The ACA did increase the number of employers who offer insurance to employees and assist in covering more people; however, some of this may change in the future if the law is repealed, new legislation is passed, or changes are made to the ACA.

Annual limits are also important as they define the maximum amount that enrollees must pay per year if health services are required; after that level is reached, they no longer must contribute to the payment for that year. For example, suppose the employee or enrollee has bills exceeding $5,000, and the annual limit is $5,000. After paying $5,000, this enrollee or patient would not have to pay any more for care that year; the patient is 100% covered for care for the remainder of that year.

Some employees may include their families in their employer insurance coverage if this is part of the employer benefit. The ACA now requires insurers to allow families to include uninsured adult children up to age 26 on their insurance, even if the adult child is no longer dependent on the parents. Typically, employees pay more per year for family insurance, and there may be different requirements for the family (for example, a higher annual out-of-pocket limit) than for individual employee coverage.

Another critical reimbursement element is preexisting conditions. A preexisting condition is a medical condition that a person developed before the person applied for a particular health insurance policy. In the past this type of condition could affect the person's (enrollee or employee) ability to get coverage or how much the enrollee must pay for it. What is considered a preexisting condition? Differences in how policies answer this question have long been a problem; however, this has changed, and legally, insurers cannot apply a preexisting condition requirement to insurers as a reason to deny insurance coverage or charge more for coverage.

Government Reimbursement of Healthcare Services

State and federal governments cover a large portion of the healthcare costs in the United States for government employees. This does not represent universal health coverage; it just covers government employees. The United States is one of the few industrialized countries that does not have universal coverage.

There are several types of government-sponsored reimbursement, which do not require government employment but do apply to certain populations. The largest programs are Medicare and Medicaid, which are managed by the CMS as part of the HHS. In 1965, Title XVIII, an amendment to the Social Security Act, established Medicare. Medicare is the federal health insurance program for people aged 65 and older, persons with disabilities, and people with end-stage renal disease. As of March 2023, Medicare had 65,748,297 beneficiaries, and this number increases each year (HHS, CMS, 2023a). The need for Medicare coverage is growing because of the increase in the population older than age 65. There are several parts to Medicare: Part A covers hospital services; Part B covers physician and outpatient care; Part C, referred to as Medicare Advantage, offers Medicare-approved private insurance plans that cover Part A and B services, but Medicare enrollees may choose one of these plans-the plans may charge different fees; and Part D provides coverage for prescriptions. Medicare beneficiaries must pay a portion of costs for Part B and prescriptions (Part D). Medicare does not pay for long-term care but does cover some skilled nursing and home health care for specific conditions.

The CMS sets standards and monitors Medicare services and payment. Medicare covers many patients in acute care today. It is a very important part of the U.S. healthcare delivery system that supports older citizens and other specified populations; however, there is concern about financing this program in the future because of the increase in the number of citizens who will be 65 and older, and this will increase costs. The CMS is also concerned about quality care, as discussed in other chapters in this text.

Medicaid, established in 1965 by Title XIX of the Social Security Act, is the federal/state program for certain categories of low-income people. Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) cover health- and long-term care services for more than 93,815,749 Americans, including the aged, the blind, disabled persons, and people who are eligible to receive federally assisted income maintenance payments (HHS, CMS, 2023b). The number of people enrolled in Medicaid is increasing, and this has been influenced by the ACA, as more people are now eligible for Medicaid due to changes in the program made by the ACA to increase insurance coverage for many. The Medicaid program is funded by both federal funds and state funds, but each state sets its own guidelines and administers the state's Medicaid program. The federal poverty guidelines establish the annual income level for poverty as defined by the federal government and are important in identifying people who meet coverage criteria for Medicaid reimbursement.

Covered Medicaid services include inpatient care (excluding psychiatric or behavioral health); outpatient care with certain stipulations; laboratory and radiology services; care provided by certified pediatric and family nurse practitioners when licensed to practice under state law; nursing facility services (long-term care) for beneficiaries aged 21 and older; early and periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment for children younger than age 21; family planning services and supplies; physician services; medical and surgical care; dental services; home health care for beneficiaries who are entitled to nursing facility services under the state's Medicaid plan; certified nurse-midwifery services; pregnancy-related services and services for other conditions that might complicate pregnancy; and 60 days' postpartum pregnancy-related services.

A second group of persons eligible for Medicaid is the medically needy. These are persons who have too much money (which may be in savings) to be eligible categorically for Medicaid but who require extensive care that would consume all their resources. Each state must include the following populations in this group: pregnant women through a 60-day postpartum period; children younger than the age of 18; certain newborns for one year; and certain protected blind persons. States may add others to this list. The federal government requires that each state cover, at a minimum, persons who qualify for Aid to Families with Dependent Children, all needy children younger than age 21, persons who qualify for old-age assistance, persons who qualify for Aid to the Blind, persons who are permanently or totally disabled, and those older than 65 who are on welfare.

Federal and state governments also reimburse care through the following organizations and methods:

- Military health care: In this system, the government not only pays for the care for all in military service but also is the care provider through military hospitals and other healthcare services. The military also covers care of dependents whose care may or may not be provided at a military facility but instead may be provided in the private sector and paid through military insurance.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: The VA provides services to veterans at VA facilities and covers the cost of these services. VA hospitals are found across the country and provide acute care; ambulatory care; and pharmaceutical, rehabilitation, and specialty services. In some cases, the VA provides care at long-term care facilities. The VA does not cover healthcare services for families of veterans.

- Federal Employees Health Benefit Program: Federal law mandates federal employee health insurance; employees may be located anywhere. Enrollees, who must be federal employees, choose from a variety of healthcare insurance plans as part of the Federal Employees Health Benefit Program. This is only a reimbursement or insurance program; it does not provide healthcare services. Enrollees receive this care through the private healthcare system.

- State insurance programs: States offer health insurance to their state employees. Typically, the state government is the largest employer in a state, and, therefore, the state's largest insurer. State employees choose from a variety of plans and contribute to the coverage in the same way that nonstate employees pay into their employer health programs and receive their care through the private healthcare system.

The Uninsured and the Underinsured

A large part of the population in the United States is uninsured or underinsured (that is, they do not have enough insurance coverage to pay for their needs). The National Health Interview Survey reported the following based on data from 2019 interviews (HHS, CDC, 2023).

- In 2019, 33.2 million (10.3%) persons of all ages were uninsured at the time of interview. In the second half of 2019, 35.7 million persons of all ages (11.0%) were uninsured-significantly higher than the first six months of 2019 (30.7 million, 9.5%).

- In 2019, among adults aged 18-64, 14.7% were uninsured at the time of interview, 20.4% had public coverage, and 66.8% had private health insurance coverage.

- Among children aged 0-17 years, 5.1% were uninsured, 41.4% had public coverage, and 55.2% had private health insurance coverage.

- Among adults aged 18-64, men (16.3%) were more likely than women (13.1%) to be uninsured.

- Among adults aged 18-64, Hispanic adults (29.7%) were more likely than non-Hispanic Black (14.7%), non-Hispanic White (10.5%), and non-Hispanic Asian (7.5%) to be uninsured.

- Among adults aged 18-64, 4.4% (8.7 million) were covered by private health insurance plans obtained through the Health Insurance Marketplace or state-based exchanges.

- Data such as the number of uninsured are always a few years behind the current year with current data found at the U.S. Census Bureau website. Data change as more Americans move in and out of the health insurance pool. In 2022, the HHS reported that national uninsured had reached an all-time low, and this significant result is described in the key findings (HHS, 2022): The nation's uninsured rate declined significantly in 2021 and early 2022, reaching an all-time low of 8.0 percent for U.S. residents of all ages in the first quarter (January-March) of 2022, based on new data from the National Health Interview Survey, compared to the prior low of 9.0 percent in 2016.

- Approximately 5.2 million people-including 4.1 million adults ages 18-64 and 1 million children ages 0-17-have gained health coverage since 2020. These gains in health insurance coverage are concurrent with the implementation of the American Rescue Plan's enhanced Marketplace subsidies, the continuous enrollment provision in Medicaid, several recent state Medicaid expansions, and substantial enrollment outreach by the Biden-Harris Administration in 2021-2022.