Objectives ⬇

- Describe nursing education in relation to the Foundation of Knowledge model.

- Explore knowledge acquisition and sharing.

- Assess technology tools and delivery modalities used in nursing education and continuing education.

- Compare and contrast knowledge assessment methods.

Key Terms ⬆ ⬇

Introduction: Nursing Education and the Foundation of Knowledge Model ⬆ ⬇

Nursing informatics facilitates the integration of information, data, and knowledge to support nurses, patients, and other providers in their particular settings and decision-making roles. The Foundation of Knowledge model specifically prompts nurses to extend their theoretical and metaphorical knowledge into practical, holistic determinations based on a variety of factors and contexts. Because competencies in informatics include but are not limited to information literacy, computer literacy, and the ability to use strategies and system applications to manage data, knowledge, and information, the ability of nursing students to use computer-mediated communication skills is essential to their success in the nursing field and as a means to improve patient safety.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused an immediate rise of telecommunications and virtual technology use in health care. At the same time, education programs were also increasing their use of virtual or online teaching strategies to meet the needs of their learners, and nursing was no exception. Now, going far beyond the simple applications of word processing software or spreadsheets, technology applications have evolved greatly, taking advantage of modern capabilities to provide nursing and related healthcare students with simulations, complex multimedia, virtual reality-assisted clinical scenarios, and a host of information- and literature-gathering internet tools.

Knowledge Acquisition and Sharing ⬆ ⬇

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a paradigm shift with the shutdowns causing the loss of clinical access and face-to-face meetings. Those who only wanted to test the waters of virtual teaching and learning prior to the pandemic were now diving in to help their students continue their educational programs. Web-enhanced courses were developed that included online chats, forum discussions, instant messaging, blogging, and use of email, all of which ask the student to engage, digest, use, and disseminate information in new ways (Figure 19-1). In addition, mannequin-based or virtual simulations replaced 25% to 50% of some clinical experiences. How nursing students learned and were career readied had changed. Karim (2021) reported that “[p]rior to the pandemic, nursing students were required to spend at least 75% of their clinical time providing direct care to patients in hospitals” (para. 12). Many Boards of Registered Nursing reviewed their regulations and permitted 25% to 50% of the clinical hours to be completed using simulated experiences.

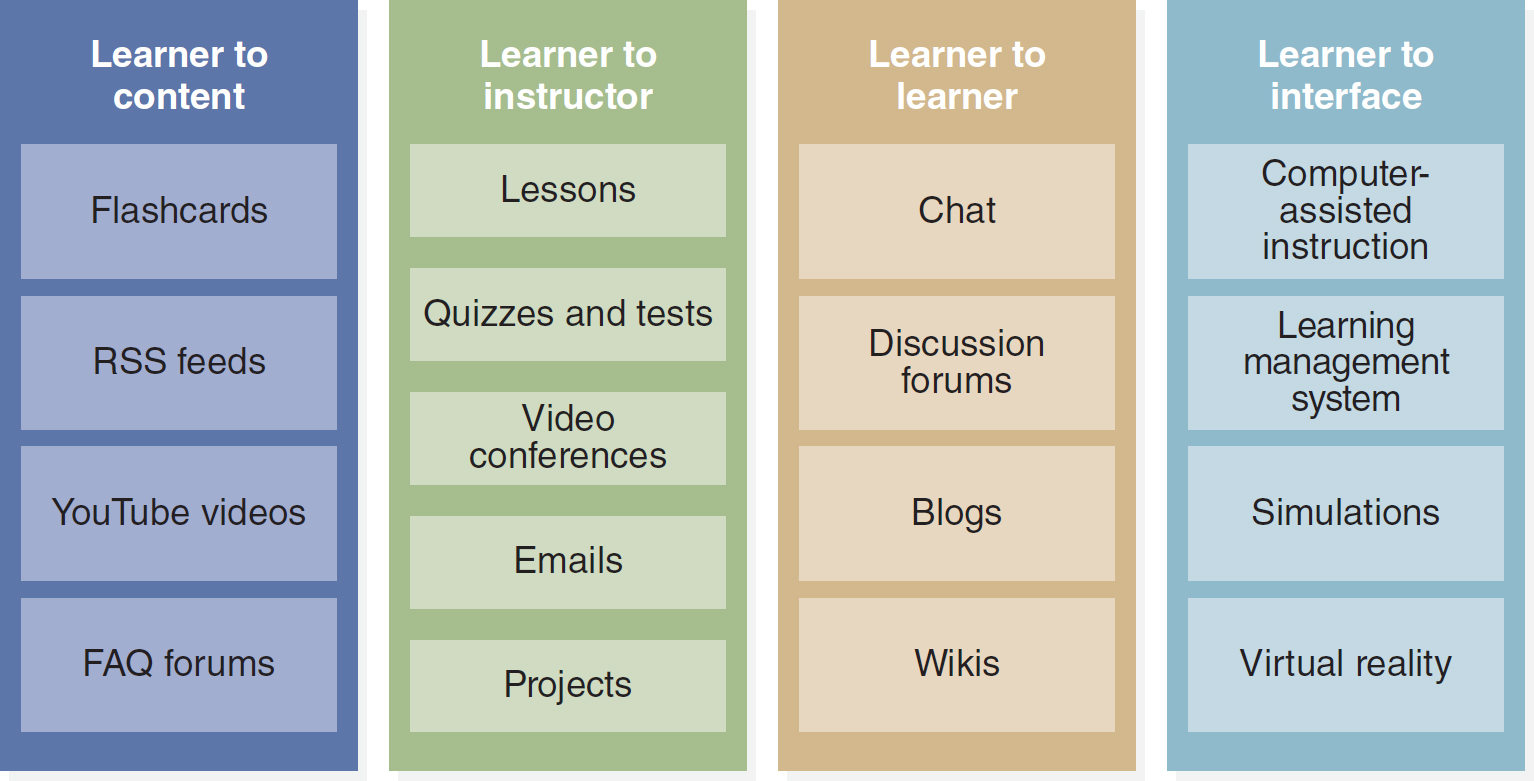

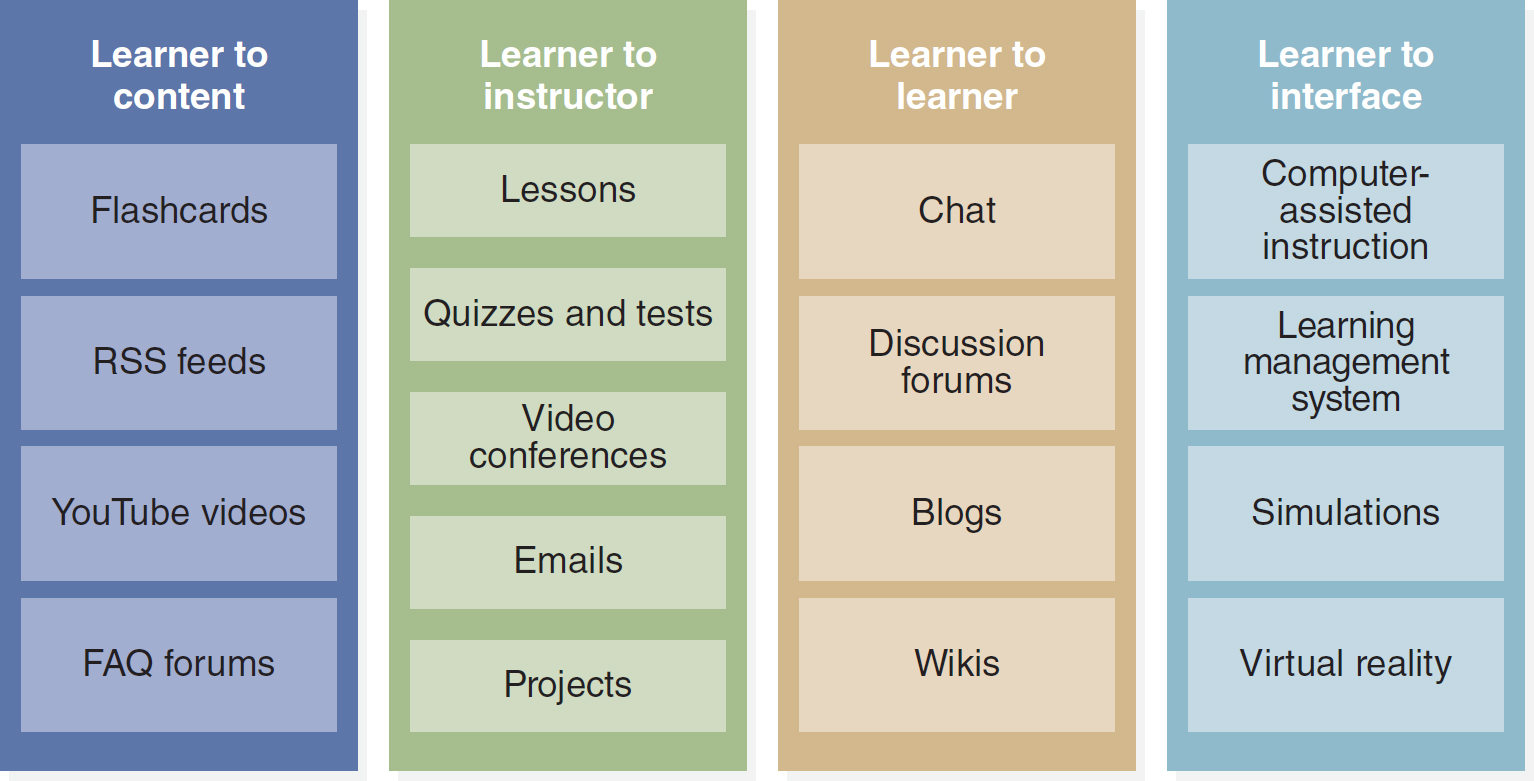

Figure 19-1 Types of Interactions in Web-Based Courses

Four boxes list the different types of interactions in various web-based courses.

The interactions are as follows. Learner to content: Flashcards; R S S feeds; YouTube videos; F A Q forums. Learner to instructor: Lessons; Quizzes and tests; Video conferences; Emails; Projects. Learner to learner: Chat; Discussion forums; Blogs; Wikis. Learner to interface: Computer-assisted instruction; Learning management system; Simulations; Virtual reality.

Data from: Juliano, R. (2014). Best practices guide to converting face to face courses to a distance learning format: Educational technology. www.manula.com/manuals/rachael-juliano/best-practices-guide-to-converting-face-to-face-courses-to-a-distance-learning-format/1/en/topic/educational-technology.

Evolution of Learning Management Systems ⬆ ⬇

Twenty-first-century nursing informatics emphasizes technology usability, functionality, and accessibility in education and practice. Consequently, the need to learn nursing skills presented endless potential for software development. Recall that software comprises the instructions that direct a computer's hardware to work, whereas hardware consists of physical computer components, such as a mouse, keyboard, and monitor. Software essentially translates commands into computer language to allow the hardware to perform its functions. Applications software refers to the various programs individuals use to communicate with others, work, play games, or watch multimedia on a computer.

When evaluating software or hardware for purchase, careful assessment of the products and services will help an educator, administrator, or student make the best choices. The most important thing when evaluating software is to understand how well the software's functionality matches the learning goals and objectives. Although many programs are available for assisting a nurse educator who is evaluating software for particular learning purposes, the main criteria are content (Is the information accurate? Is it relevant?), format (How is information visually presented? Is it in frames? Does it come with graphics?), documentation style (What is the tone? Is it scholarly and applicable?), and strategies (Is the software useful for all students, including students with disabilities and remedial and accelerated students?) (Edwards & Drury, 2000). In addition, consider diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

Hardware decisions depend on the way a computer system will be used in addition to considerations related to cost, ease of use, and durability. Systems purchased for personal use may differ dramatically from those purchased for online learning, virtual simulation, or smart classrooms. Remember that you must always consider the level of security that is needed. Because the technology inherent to workstations, servers, and computers, in general, tends to change rapidly, discussing large-system decisions with an information technology expert is likely to yield a better-informed decision. Other hardware considerations arise from the use of virtual simulation, including the realities and, specifically, virtual reality (VR). What type of head mounted-display (HMD) and controllers will be needed, and if entering the VR environment in non-VR, does this affect the type of computer the learner will need? Education innovators realized the need for additional functionality. Integrated learning systems have evolved from tracking, content management, and more individualized instruction or primarily the administration of the course and content, providing convenience for instructors and learners. The learners typically had only one learning management system (LMS) to learn. The LMS was used throughout the program, and the faculty and learners became proficient in its use. The next evolutions that are still in progress are the transition to a learner-centered approach and the integration of adaptive learning. Learning should be tailored to the learner, thus allowing them to have control over their learning, such as how they engage with the content and the pacing of learning. This means that the content must be available in a variety of formats to meet the learning style of each learner as well as providing teacher support and additional content delivery methods for clarity if they do not reach mastery. The LMS with integrated adaptive learning will not only track mastery but also be able to help the student achieve it. The faculty member must be able to offer any necessary support to each learner while monitoring the progress and needs of all the students in the course or learning episode.

Delivery Modalities ⬆ ⬇

Nursing educators are discovering that today's learners may not always respond in the same ways that the educators did during their own tenure as learners. Technology-savvy learners from the millennial age demand instant information delivered in an entertaining fashion, an expectation built on extensive exposure to email, text messaging, online chatting, and the internet (Ridley, 2007). In addition, many nursing departments are facing an increase in student enrollment and a corresponding growth in faculty. Although new nursing faculty members bring significant clinical experience to their academic positions, also apparent for some is an underlying tension and unfamiliarity with technological advances, outcomes-based accreditation initiatives, and teaching itself. Schools of nursing are scrambling to provide professional development for busy nursing faculty members and introduce them to best practices in teaching (Shaffer et al., 2006).

Learning is a multispatial function, and in the age of technology innovation, instructional delivery can inhabit many forms in both physical and virtual spaces. Spaces in academia are no longer defined by a class or its content but instead by the learning the class is trying to promote. To this end, learning spaces should support multiple modes of learning and delivery, including reflection, discussion, and experience, and facilitate face-to-face and online interaction within and beyond classrooms. Truly innovative delivery must support the learning activities whether in face-to-face classroom interaction, online engagement, virtual simulation, the realities, or a blended hybrid of technology and traditional classroom teaching.

Face-to-Face Delivery

Ridley (2007) suggested that although it is the most widely used teaching method among nurse educators, traditional face-to-face lecture yields only a 5% information retention rate over a 24-hour period, a rate that compares unfavorably with demonstration (30%), discussion groups (50%), practice activities (75%), and peer teaching (90%) (as cited in Sousa, 1995).

In addition, the inability of physical space to keep pace with the evolution of learning models inhibits the benefits gained from face-to-face interaction between teacher and student. For example, collaborative learning grinds to a halt when class is held in a room with chairs bolted to the floor, facing a lectern (Oblinger, 2005); this kind of spatial arrangement prohibits a sense of classroom community by inhibiting easy peer interaction, reducing students' ability to see one another, and concentrating all attention on the professor.

Conversely, in a collaborative learning environment, the professor guides conversation and sets up discussion, acting less as the classroom authority and more as a facilitator, helping students maintain focus, gently guiding discussion, and ultimately empowering students to push knowledge boundaries in a safe and secure atmosphere of peer support. This inductive, epistemological approach promotes active, critical thinking skills and assists students in learning not just facts but also how to learn. As future healthcare professionals determined to rely on quantification and rationale, nursing students will benefit from face-to-face classroom interaction that hones their ability to manufacture new personal truths through interaction with people and ideas in ways that cannot always be measured and counted.

Ridley (2007) suggested that such interactive, cooperative learning strategies might include gaming, role-playing, and problem-based learning. Because games are nonthreatening and fun, they promote critical thinking and teamwork by pushing students to work together in groups to find answers and achieve success. Role-playing is similar in that it allows students to try on real-life scenarios by filling either scripted or ad-libbed roles (e.g., doctor, nurse, patient, or clinician) without the fear or pressure of putting another's life at risk while trying to determine the best course of action or find a solution for a fictitious patient's health issue.

Problem-based learning, a well-accepted form of interactive learning, takes assignments out of a contextual vacuum and applies real-life scenarios to problems or challenges. Students work in groups to solve the dilemma presented by real patient cases and build on prior knowledge, using higher-level thinking skills and progressive inquiry to resolve the problem (Ridley, 2007). This process enhances the student's critical skills for acquiring and maintaining knowledge in practice.

Online Delivery

E-learning, online learning, and web-based education have caused a significant shift in learner-teacher relationships in nursing education. According to Oblinger (2005), not only are learning spaces no longer physical or formal, especially on campuses with wireless capabilities, but nursing students also expect to make use of wide ranges of cutting-edge technology during their academic tenure, exchanging the traditional “sage on the stage” for a technologically savvy “guide on the side” (Leasure et al., 2000) who gives up the role of gatekeeper and instead promotes and facilitates dialogue as central to teaching and learning (Aquino-Russell et al., 2007).

Learner centered and no longer limited to the domain of the classroom, laboratory, or even a patient's bedside, online learning allows educators to translate theory into practice by creating a virtual classroom space that promotes collaboration, engagement, discussion, and analysis. Studies show that web-based courses not only continue to gain in popularity but also enhance learning in ways that encourage learners to share personal experiences and support. Researchers cite many factors that make online learning laudable, with accessibility and convenience being two of the most frequently cited issues (Aquino-Russell et al., 2007).

The asynchronous and time-independent elements of web-based courses respond to the huge need for flexible class times among today's growing population of nontraditional learners. In addition, web-based and place-independent learning allows anyone with access, anywhere in the world, to participate. Exposure to online learning during healthcare professional education programs will facilitate continuing professional education during the practice tenure. Related to this issue is the democratizing effect of online learning such that all students have the same opportunity to participate without judgment. Web-based classes provide an easily accessible permanent record, a convenience for both teachers and learners (Aquino-Russell et al., 2007).

One of the challenges and criticisms of online education has been that the instructor does not know whether the student enrolled in the class is actually the person who takes the test or writes the paper. But the same can be said for instructors in face-to-face classes regarding who actually completes papers and out-of-class assignments. The only sure thing is that if students test in a classroom with the instructor, the instructor knows that they are the ones taking the test. Thus, verification of students' identity is critical to ensure that credit is given to the student who completed the work or took the test, especially in an online testing environment. Learner identity verification tools continue to evolve. Some critics believe that as with other technologies, students can find work-arounds. To meet the federal regulations and secure the testing environment, many believe that instructors should use one or more identity verification tools combined with a method for live proctoring. It is imperative that nurse informaticists and information technology experts work with educators and administrators to determine the technology tools necessary to accomplish student identity verification, based on their specific infrastructure and needs.

It is important to use tools that facilitate learning, such as introducing social media into nursing education. X (formerly Twitter; https://twitter.com/home) can be used to focus and hone student perspectives. Each posting, or tweet, cannot exceed 280 characters. As learners critically think about what they want to add to the discussion, they must act as wordsmiths to express their views succinctly and concisely given the character limitation. Other social media that can be used in education include the following sites:

- Diigo (www.diigo.com), a social bookmarking tool to collect, tag, and share online sources (Meyer, 2015)

- Feedly (https://feedly.com/i/welcome), an online feed aggregator to notify the subscriber of new content on blogs and websites of interest (Meyer, 2015)

- Flickr (www.flickr.com), for photo sharing

- Instagram (www.instagram.com), for customizing and sharing photos and videos (Meyer, 2015)

- Pinterest (www.pinterest.com), a social bookmarking tool used to prime discussions (Meyer, 2015)

- Pixton (www.pixton.com), to create comics or cartoons

- Prezi (https://prezi.com), to create zooming presentations

- Scoop.it (www.scoop.it), an online content curation tool used to collect web resources, comment on them, and publish the source and commentary (Meyer, 2015)

- SlideShare (www.slideshare.net), a community for sharing presentations

- YouTube (www.youtube.com), to watch and share videos

- VoiceThread (https://voicethread.com), to share images, videos, documents, and commentary (Meyer, 2015)

- Wordle (www.wordle.net), to create word clouds from text

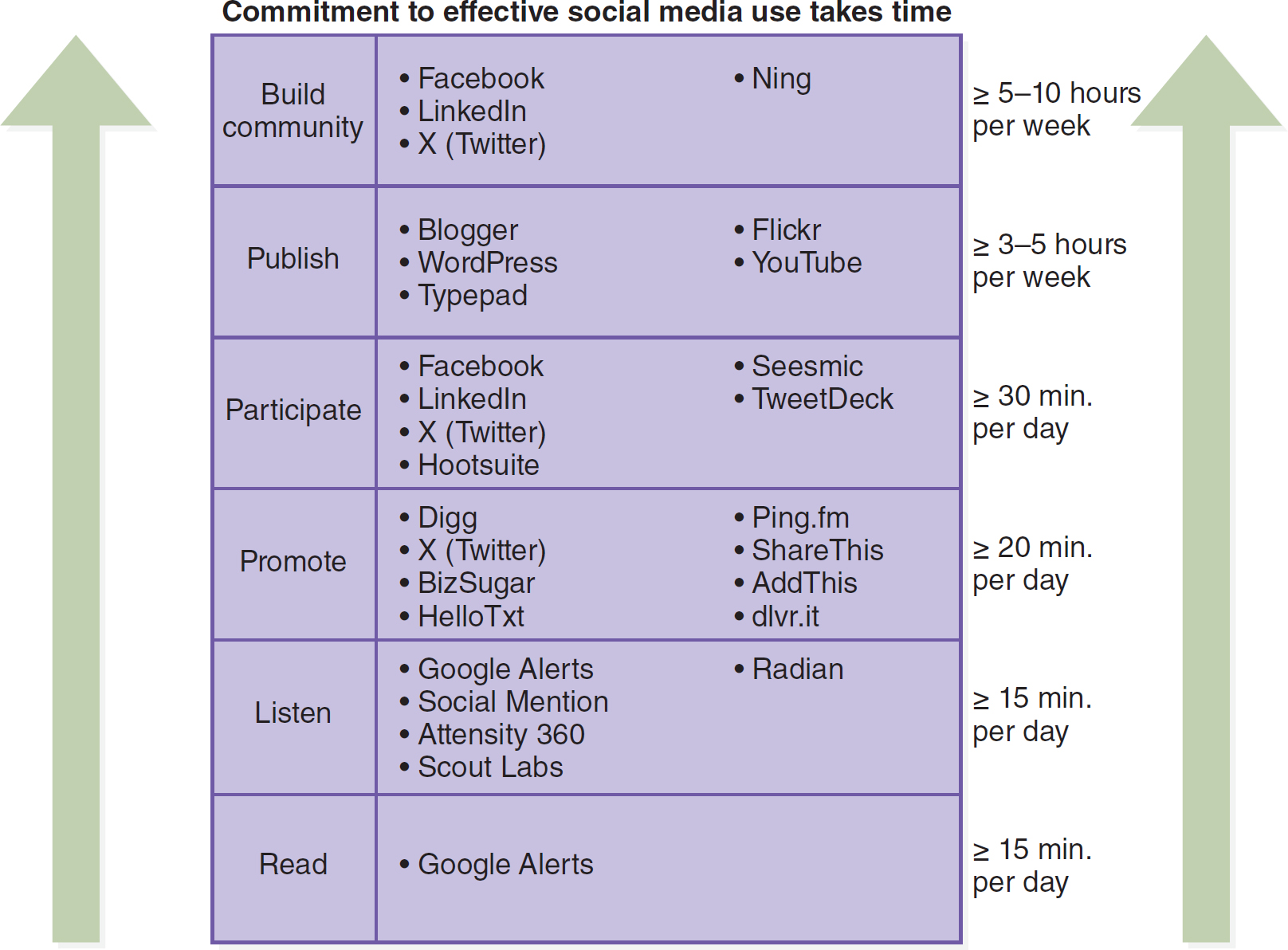

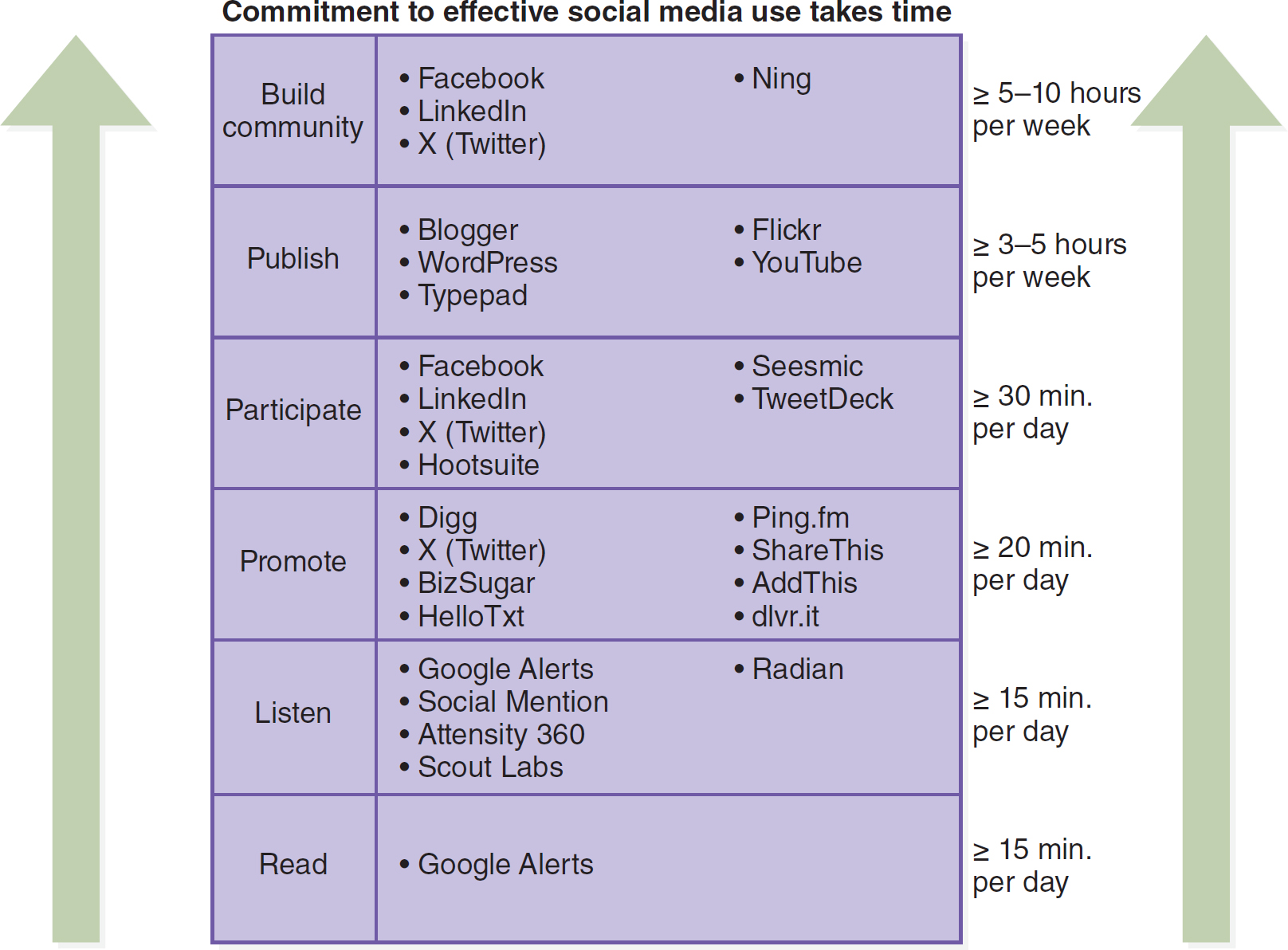

Students can use these sites to facilitate their presentations and for team collaboration. The use of social media not only exposes the students to their use but also promotes the development of skills that will support professional collaboration as students enter the practice arena. Meyer (2015) reported that using social media in education helps students put concepts in context, maintains currency in course content, and fosters a sense of community. Figure 19-2 demonstrates the purposes and time required for proper use of social media.

Figure 19-2 Social Media Time Estimates

A tabular illustration underscores the necessity of dedicating time for the effective use of social media.

The illustration features a table with an upward arrow on either side. The table is titled Commitment to effective social media use takes time. The row entries are as follows. Row 1. Build community: Facebook; LinkedIn; X, Twitter; Ning. More than 5 to 10 hours per week. Row 2. Publish: Blogger; WordPress; Typepad; Flickr; YouTube. More than 3 to 5 hours per week. Row 3. Participate: Facebook; LinkedIn; X, Twitter; Hootsuite; Seesmic; TweetDec. More than 30 minutes per day. Row 4. Promote: Digg; X, Twitter; BizSugar; HelloTxt; Ping.fm; ShareThis; AddThis; dlvr.it. More than 20 minutes per day. Row 5. Listen: Google Alerts; Social Mention; Attensity 360; Scout Lab; Radian. More than 15 minutes per day. Row 6. Read: Google Alerts. More than 15 minutes per day.

Data from: Holly A. (2016). Find 10 tips that help you take time to be social. The Social Observer. www.thesocialobserver.com/take-time-to-be-social.

| Educational Applications for Blockchains and Distributed Ledger Technology |

|---|

| As you read about these applications, envision how this technology could work, and think about other educational uses for it. |

| Decrease Fake Diplomas |

|---|

| There are more than 200,000 fake diplomas sold by fake diploma mills every year in the U. S., and recently there were arrests surrounding more than 7,600 fake nursing diplomas issued from Florida schools alone (Bernstein, 2023). The verification process is personnel intensive, and some have suggested that blockchain technology can be used to store these credentials. Learning Machine “has collaborated with the MIT Media Lab to launch Blockcerts-an open infrastructure for creating, issuing, viewing and verifying blockchain-based certificates” (Vander Ark, 2018, para. 4). The issue of diploma fraud and fake diplomas could be eliminated with the use of blockchains because Blockcerts would facilitate verification of blockchain educational credentials (McArthur, 2018). According to Coca (2021), if all institutions would put blockchain in place to protect against fake information, the number of diploma mills and fake universities would decrease. |

| File Storage and Security |

|---|

| Educational entities must protect their student information from being corrupted, altered, or lost. Distributed ledger technology (DLT) cloud storage could offer a safer and less expensive alternative to traditional options (Vander Ark, 2018; Yedigaryan, 2019). |

| Library Holdings |

|---|

| DLT could facilitate a library's expansion of its “services by building an enhanced metadata archive, developing a protocol for supporting community-based collections, and facilitating more effective management of digital rights” (Vander Ark, 2018, para. 34). |

| Credits or Credentials From Multiple Educational Entities |

|---|

| Blockchains or DLT could track and maintain credits received over time from multiple educational entities. This technology would provide authentic, verifiable, accurate records of student credentials and competencies (McArthur, 2018).

|

Hybrid or Blended Delivery

Traditional courses are more frequently being offered as online virtual classes (i.e., distance education)-learning that occurs other than in the traditional classroom and consequently requires special course design, planning, techniques, and communication. A hybrid of this delivery mode includes learning in which traditional classroom time is enhanced or broken up with online components, thereby creating a class in which blended learning occurs. Forms of hybrid learning include web-enhanced learning, such as asking students to blog responses to a reading or class discussion, and learning that takes place in and makes use of smart classrooms (e.g., teaching in a wired room equipped with classroom learning technologies).

Smart classrooms, also known as digital and multimedia classrooms, integrate computer and audiovisual technologies by providing a ceiling-mounted projector with an access point at the front of the room, an instructor podium or workstation, sound, and network access. An enhanced smart classroom also provides networked student workstations instead of traditional desks, allowing students to follow along online and perform network or web searches, chat, blog, or a myriad of other activities as directed by the professor. For example, at the Penn State College of Nursing, users can access announcements, course materials, faculty information, websites, and other tools through the electronic course management system, which enables the nursing faculty to extend learning beyond the physical classroom walls.

Competency-Based Learning

More robust LMSs are particularly well suited to support competency-based learning. Nursing competencies have been well defined by professional and accrediting organizations, such as Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN); American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), through its Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform (TIGER) initiative and the essentials of nursing education delineated for undergraduate and graduate study; and Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), through its promotion of informatics competencies.

Database technologies within LMSs offer the ability to track competency achievement, as Pijl-Zieber et al. (2014) explained: “Such technologies could be shared, at least to some degree, between nursing student and nursing instructor, much like clinical evaluation tools are shared on paper, to jointly track skills, knowledge, abilities, critical thinking, clinical reflection, and developing competence” (p. 677).

Technology Tools Supporting Education ⬆ ⬇

Certain social trends emerging from the morass of both traditional and innovative technology tools include the use of technologies attempting to meet the needs of members of the Net Generation, or the millennials (i.e., those born between 1981 and 1996). These students have grown up inside a wired world of instant access and online everything, and they are connected, digital, experiential, and social learners. Through the use of software, hardware, drivers, dedicated servers, plug-ins, and internet connections, students can chat, collaborate, play games, or interact electronically with a peer in some way, all with little to no learning curve or effort. Because visual media are now the vernacular of this highly digital culture, such tools might take the shape of interactive tutorials, a created city within a virtual reality landscape, high-fidelity simulations, serious games, or even a multimedia action maze that prompts users to choose different outcomes within a scenario. Generation Z (Gen Z) learners are those born between 1997 and 2012. Schrader (2022) believed that their learning must be flexible so that they can self-pace and be highly collaborative in nature. These learners want their reality to be seamless from the real world through any of the virtual reality experiences.

Members of Gen Z are entering nursing schools and the workplace. This generation is currently the most racially and ethnically diverse of all the other generations, and they are very comfortable with technology, especially when using the internet and wireless devices to obtain information when they need it. The number of technologies and devices they use could cause them to mainly interact virtually; their expert use of sophisticated digital tools could result in immature social skills and the inability to make and maintain relationships, placing them at risk for isolation and related issues of anxiety, loneliness, and depression. Stillman (2019) stated that “about half of Generation Z spend 10 hours or more each day online. . . . [The] favorite social media sites of Generation Z include Instagram, YouTube, and Snapchat” (para. 2). Gen Z will be a 2.56 billion population by 2020. When Gen Z grows up, they'll make up 40% of U.S. consumers. In view of the size of the Gen Z population, all educational institutions must consider and adjust to their learning needs (Morgan, 2020; Todorov, 2023).

Regardless of the particular tool employed, technology can perform only as well as the pedagogy that drives it. Therefore, the faculty and learners must be considered and supported in order to sustain the nursing programs.

Tutorials

The modern tutorial mimics lectures by guiding users through a series of objectives or tasks, which they are usually allowed to complete at their own pace (Edwards & Drury, 2000). Generally, tutorials stand alone as autonomous multimedia that may use animation, text, graphics, sound, questions, and various kinds of interactivity to engage and intrigue the user. They tend to promote active learning by prompting users to answer sets of questions, follow clickable hypertext, or complete quizzes. For example, users might be asked to fill in worksheets after reviewing anatomy concepts, take a quiz, post an answer to a question, or click through a scenario by choosing the best course of action in a mock clinical situation.

Some tutorials, such as those used by medical students at the Morgan Stanley Children's Hospital of New York, are designed to be brief (10 minutes), interactive, very focused, and immediately relevant. In this case, medical students bustling through a busy clinical rotation who accessed the tutorials actually raised examination grades (Pusic et al., 2007).

Because most students benefit from being able to contextualize a lesson's framework and purpose, the most effective tutorials provide users with understandable navigation, such as a table of contents at its beginning, or additional navigational aids, such as icons, buttons, or text, that indicate where and how they need to progress (Dewald, 1999). Effective tutorials surpass the simple presentation of information in a web-based format; instead, they address certain pedagogical and student-centered needs by identifying and considering specific factors, such as instructional content, the educator's purpose and teaching goal, the initiative's overall purpose, the potential need for special conceptual input, the learners' ultimate objectives in completing the tutorial, and the standards that determine what qualifies as successful completion of the tutorial (DeSantis, 2002).

Although most tutorials are created to stand alone, some of them may also benefit and supplement face-to-face instruction, such as the interactive information skills tutorial developed at the Institute for Health and Social Care Research in Salford, United Kingdom. This tutorial divides a traditional lecture series into chunks and incorporates questions into the text that would normally arise during the session and provides hyperlinks to the answers. This organization allows users to browse to different parts of the tutorial, open a database in a new window to perform a practice search, and access other features (Grant & Brettle, 2006). In all their iterations, tutorials urge students to hone and develop effective critical thinking skills. Short tutorials may also be created on an organization's intranet to educate practicing professionals on a new policy, procedure, organizational initiative, or healthcare technology. Since the tutorial is electronic, access and time spent on the tutorial can easily be tracked.

Case Scenarios

Professional organizations are increasingly recommending performance-based assessments of students in professional degree programs, and enacting case scenarios provides an opportunity for students to practice procedural responses and improve patient safety. The case scenario, a form of problem-based learning, has evolved and is now available through simulation software and virtual reality programming. This kind of learning assessment, in which students must respond within context to a perceived situation rather than a theoretical or fact-based question, allows educators to gauge procedural knowledge and determine how well a student executes a skill or applies concepts and principles to specific situations (Garavalia et al., 2008). For example, in a clinical context, a student could explain a specific procedure, but such knowledge is declarative rather than procedural; therefore, for some evaluators, it is not as valuable. Conditional knowledge is also often reflected in procedural knowledge that demonstrates a student's ability to know when and why action is or is not taken and how. As more programs move toward interprofessional education, case scenarios are a great way for students to hone collaboration skills and gain an understanding of the roles of other professionals.

Portfolios

Portfolios in healthcare professional education have grown in popularity as useful tools for documenting students' exposure to educational experiences. A portfolio allows a student to document a variety of unquantifiable skills, such as creativity, communication, and critical thinking. Further, portfolios can reflect achievement of goals, self-evaluation, and professional development and provide a way for returning students to log and document past work or life experiences in a creative but structured way without taking a standardized test. The usefulness of a portfolio for an undergraduate depends on a structured system of organization, such as an identification page with a resume, a table of contents, and separate and clearly marked sections. In this way, portfolios can monitor program outcomes, positively influence employment and graduate school admission, and provide a clear snapshot of a student's strengths and abilities. See Box 19-1 for an overview of electronic portfolios and specific information on developing a professional portfolio.

| Box 19-1 What Is an Electronic Portfolio? |

|---|

| Glenn Johnson JeffSwain

Today's information technology infrastructure allows users to easily build web-based collections that include evidence of their knowledge and skills. Users can upload artifacts that represent evidence of their learning experiences, inside and outside of the classroom. Electronic portfolios (e-portfolios) may also contain a blog element where students reflect on their total experience and demonstrate growth in their areas of study.

E-portfolios can be built using a range of technologies. Some individuals use PowerPoint presentations to capture and present evidence. Web-based e-portfolios are built using common web publishing tools to create web pages, such as Web 2.0, Web 3.0, or open source tools; the web pages are then published on the internet. Web 3.0 and an increasing number of institutional e-portfolio systems have emerged to transform how students, educators, and institutions can log on and then upload, enter, and share information or evidence related to their experiences. Students and educators can interact, collaborate, and share learning accomplishments. Examples of e-portfolio systems include the following:

|

|

| Why Create an E-Portfolio? |

|---|

| Although academic institutions may use e-portfolios for assessment of student learning, for the individual, e-portfolios are all about opportunity. Such opportunities might include supporting a working relationship with a mentor, networking with other professionals, or representing certain qualities and characteristics to prospective employers. The e-portfolio allows students to track, monitor, and assess their learning to gain significant insights throughout their program of study. In all of these cases, going through the process of developing an e-portfolio requires critical examination of which qualities make individuals who they are and why these qualities are important to them and their profession. It is important for all professionals to have a foundational understanding of where they are in their career trajectory and how this fits with their long-term professional goals.

Practically speaking, e-portfolios are efficient. When introducing oneself in an email message, a self-starting individual who has taken the initiative to develop and publish an e-portfolio can add this line to the message: “Here is a link to my e-portfolio.” The recipient can click on this link, which automatically opens that individual's e-portfolio in a web browser. Metaphorically, the senders of such messages have just walked into the recipient's office with information that illustrates who they are, what they know, what they can do, and what they value as important; they have just walked in with what could be a multimedia showcase of their qualities. The internet is a very powerful communication medium, and individuals with professional e-portfolios are simply taking advantage of this fact.

|

| E-Portfolios in Higher Education |

|---|

| As an instructional strategy, portfolios have been around for a long time. Instructionally, portfolios, whether electronic or paper based, require students to demonstrate or provide evidence that they have attained specific learning outcomes. For instance, in the arts, portfolios have been used to demonstrate the depth and breadth of the work of an artist. Although performance-based programs of study are more likely to be familiar with the concept of the portfolio as a demonstration of what a student knows and can do, other areas of study have also begun to adopt this method of assessment.

Portfolios can be particularly helpful in areas where higher-level thinking and analysis are essential. For instance, being a good healthcare professional encompasses much more than simply being able to get high scores on examinations. Professionals need to be able to collect information, analyze the information presented and relate it to past experience, apply related knowledge, and evaluate various options and, from all this, present a diagnosis and a plan of action. In short, healthcare professionals need to be able to think critically and make informed decisions. In learning to become a healthcare professional, portfolios can be used to capture, support, and improve this type of thinking as it develops.

Like the artist, the healthcare professional student can connect, share, and present cases and findings and include with this evidence the reflective commentary that serves to unveil how they arrived at a decision, which information or experiences were vital, and how their action plan evolved. However, given the vast variety of evidence that individuals might potentially use to represent themselves, what should one select, and how should this be shared?

|

| E-Portfolios for Professional Development |

|---|

| Using an e-portfolio to support professional networking involves a predetermined and focused purpose. This purpose may be to foster better communication between oneself and a mentor, or it may be to establish how what a professional is doing fits with the goals of the institution for which the individual works or would like to work. A professional e-portfolio is evidence based and uses this evidence to make a case that highlights the individual's capacity not only to perform but also to grow and develop professionally within their chosen field. |

| The E-Portfolio Process |

|---|

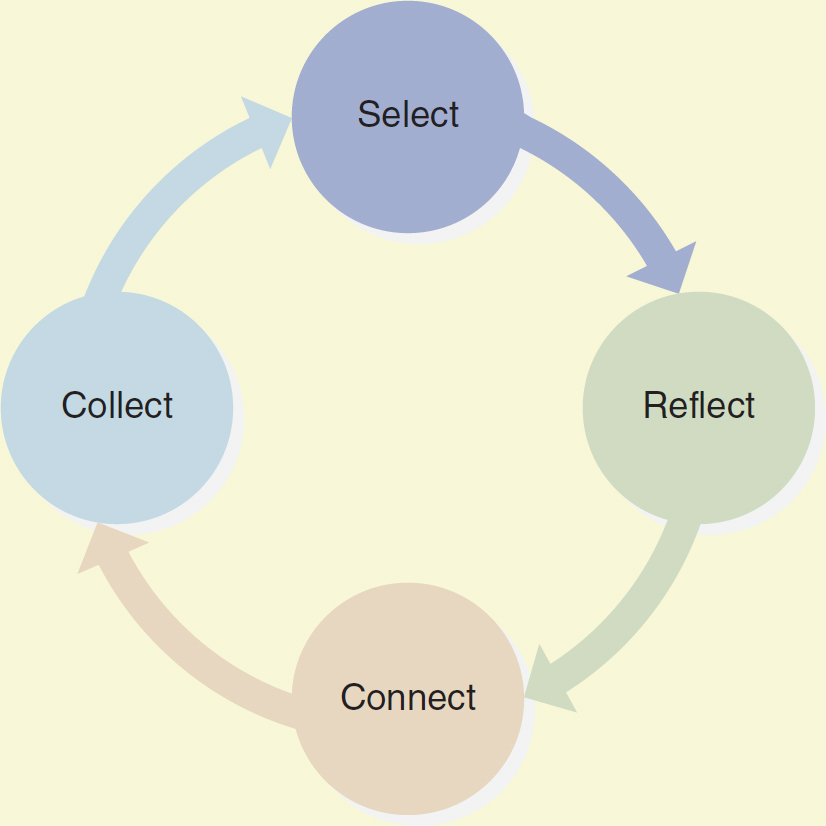

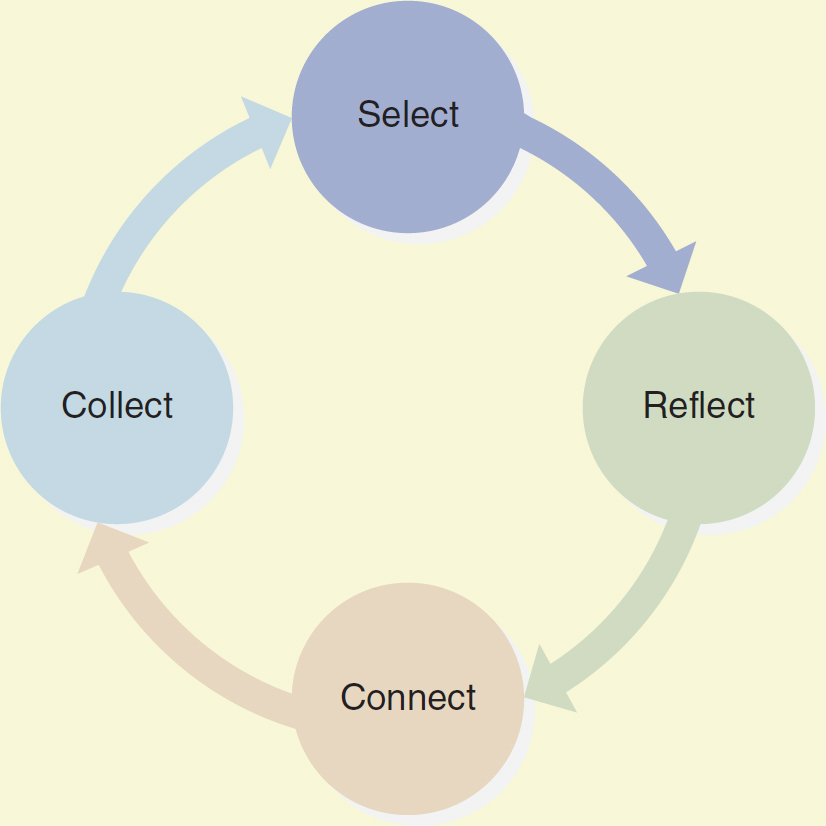

| The four steps involved in developing an e-portfolio are recursive in nature, meaning that during the process, one can backtrack to fill in missing pieces or reevaluate earlier decisions that were made. The four steps are (1) collect, (2) select, (3) reflect, and (4) connect. See Figure 19-3 for an image of the portfolio creation process.

Figure 19-3 Portfolio Creation Process

A cyclic diagram depicts the stages of the portfolio creation process: collect, select, reflect, and connect.

Collect

Evidence should demonstrate what a person knows and can do or the values that they hold as being important. When it comes to developing e-portfolios, it is important to think of evidence in very broad terms. This evidence might include the results of what someone has learned in courses taken as a student, especially in terms of demonstrating a new skill or knowledge of a subject. More importantly, evidence can come from experiences that take place outside of the classroom. For instance, someone may have been involved in an internship or clinical observation where they had the opportunity to connect what was learned in the classroom with how this information is applied in a real-world setting. Such an experience not only is valuable but also represents the individual's understanding of how this knowledge can be applied; thus, it enhances others' perceptions of the depth of what the person knows.

Resumes are evidence documents. They are very important, and every professional should have an updated copy available. However, resumes simply list an individual's experiences or accomplishments. By comparison, e-portfolios go beyond the resume to emphasize personal attributes that are very important in the specific profession. These attributes include, but are not limited to, interpersonal skills, leadership skills, appreciation of diversity, ability to work in a team, and self-sufficiency. These attributes are difficult, if not impossible, to demonstrate in a resume. When reflective commentary accompanies evidence of an individual's involvement, these attributes and values can become the highlights of an e-portfolio.

Select

Everyone has their own unique pool of evidence from which to pull, and over time this evidence pool can become quite large. What will someone choose to feature and why? Putting together a professional e-portfolio requires that several intertwining questions related to purpose and audience be addressed.

What is the purpose? What is it that someone is attempting to gain by putting an e-portfolio together? Is the purpose related to personal development (i.e., feedback and advice about the professional direction that is being taken)? Is the purpose to connect with colleagues? An individual may, for example, be interested in using their e-portfolio to find a job or gain admission into a graduate program.

Although an e-portfolio can link to everything that a person has accomplished, this may not be the best strategy. Instead, it is essential that an individual consider the audience and establish a plan that enables them to select the most appropriate pieces of evidence for their particular purpose and audience. A helpful way to start is to select the top five pieces of evidence that support the plan. Next, the individual should consider why they selected these pieces of evidence. What is it about each piece of evidence that makes it representative of who the individual is and what they know, can do, and value as important?

Reflect

Reflection and reflective commentary take an e-portfolio to the next level. This component may take the form of a single reflective statement, or it may be attached to the evidence throughout the e-portfolio. Reflective comments should open up a window into why an individual thinks this evidence is important, the ways in which the individual values what they learned, or why the individual thinks it is important for the larger profession. For instance, the individual may present an experience where they were challenged to provide assistance. Describing this experience would be important; however, the reflective comments can extend this description, enabling the individual to talk about the alternatives considered as the basis for how they made a decision to provide the specific type of assistance and the manner in which it was provided. By itself, a description of this experience is good. With reflective comments, readers have a much more thorough perception of and insight into an individual's professional thinking. This is where having a blog element as part of an e-portfolio becomes extremely powerful.

Unlike static web pages, a blog page is a space designed to be interactive. The blog owner posts commentary, thoughts, and experiences for others to read and respond to. Regular entries on a blog give others a reason to return to one's e-portfolio site repeatedly. It is an opportunity to share one's perspective on topics of interest and is critical to the chosen field. A blog is a place where conversation happens. It provides a nice counterbalance to the static web pages, such as a resume and project pieces.

Most blogging platforms allow users to select from a range of templates, which include a blogging element along with static web pages. Platforms such as WordPress, Moveable Type, and Google are free for at least the basic service, which enables the user to create a dynamic e-portfolio without having to build web pages. Most platforms allow entries to be in both text and multimedia format, so the blog becomes the perfect place for personal expression. A blog is quickly becoming a standard part of an e-portfolio.

Connect (Connections) and Feedback

The connection and feedback step is important to validate the assertions people make about what they know, understand, or value. Individuals may choose to receive feedback from those who are close to them and then from there reach out to others, who may provide different perspectives. For instance, if healthcare professionals were thinking about using their e-portfolio to apply for a position, they might want to start by getting feedback from friends and family. They might also share their e-portfolio with a mentor or faculty member, which raises the bar by getting professionally grounded feedback before sharing their e-portfolio with a prospective employer.

|

| Challenges and Issues: Privacy and Security |

|---|

| The ease and popularity of web-based social networking and professional e-portfolio tools also raise several challenges and issues for users. Never before has information for individuals been so accessible, nor has such personal information been so readily made public. For this reason, issues related to privacy and security need to be addressed. What might be appropriate socially can be deadly in a professional context. |

| E-Portfolio Process: Summary Comments |

|---|

| In summary, one might think about the process of developing a professional e-portfolio as boiling down to the telling of a rather simple story, albeit a story that has three parts: looking back, looking around, and looking ahead. Readers should think of their own evidence pool as they answer these questions: |

- Looking back: What have you done? In which activities and with which organizations have you been involved? Where have you been? With whom have you worked? How did this help get you where you are today?

- Looking around: In what are you currently involved? Why are you doing this? What are you getting out of it?

- Looking ahead: Where would you like to be in 2 years? Where would you like to be in 5 years? Why do you feel this way? What makes you think your goals are realistic?

|

Simulations

Simulations have been widely used within healthcare circles, but they experienced a recent upsurge due to the pandemic and the widespread availability of high-quality simulation equipment and software along with a reduction in the cost of this technology. Ranked by fidelity, or the level of realism the equipment provides, simulation may take various forms, from mannequin-based to computer-based simulation in which software is used to simulate a subject or situation (e.g., an interactive tutorial featuring a nurse-patient situation) to full-scale simulation in which all the elements of a healthcare situation are recreated using real physiology, people, and interaction to, as closely as possible, resemble a real-life environment. These immersive virtual simulations make the learners suspend reality and feel like they are really in the situation. Simulation scenarios aid nursing instructors in assessing competency achievement. For a more comprehensive discussion of simulation as a teaching and learning tool, please see Chapter 20, Simulation, Game Mechanics, Virtual Worlds, and the Realities in Nursing Education.

Virtual Reality

In traditional virtual reality (VR), the user receives multiple sensory inputs either mediated or generated by a computer through nasal stimulation as smells or scents, visual stimulation (i.e., glasses, goggles, and screens), audio input (i.e., earphones, microphones, and synthesizers), and touch (i.e., gloves and bodysuits). A form of simulation training that was once considered a science fiction technology of the future is the increasing use of virtual reality healthcare training.

Because virtual worlds foster unintentional learning through gamelike technology in which students discover and create knowledge to accomplish something rather than experiencing traditional outcome-based learning, their experiences may result in greater comprehension and deeper knowledge. In a virtual clinical scenario, for example, a simulated, immersive environment presents invaluable learning opportunities for the student who is assuming the role of healthcare provider. Faculty can monitor the interaction and interrupt as necessary to leverage those teachable moments and assess the learner's thought process and proposed next actions to apply specific skills within a clinical setting. Scott (2018) stated that VR “is being incorporated into college classrooms all over the country. Making sure they [the classrooms] are ready for deployment is just as important as the lessons being taught” (para. 1). This surge occurred prior to the pandemic and then the pandemic helped to continue its use. Because so much of the data nurses rely on are complex and because so many patients' cues are lacking in concrete language or responses, the animated, immersive, three-dimensional environment of virtual worlds allows students to practice skills, try new ideas, and learn from their mistakes while receiving feedback from educators within a globally networked classroom environment. Virtual reality tools are a great way to implement competency-based education. Some students may struggle to participate in virtual communities for various reasons. Increasing comfort with multidisciplinary learning among students and educators improves patient safety and encourages the refinement of best practices. Chapter 20, Simulation, Game Mechanics, Virtual Worlds, and the Realities in Nursing Education, provides a more comprehensive discussion of this technology.

Internet-Based Tools ⬆ ⬇

The consensus in nursing education suggests that any technology that allows users to interact and engage with materials and one another is useful. More specifically, the Foundation of Knowledge model qualifies this observation with the caveat that technology must display user-friendly capabilities to provide benefits to its users, thereby allowing students not just to find information and one another online but also to engage, challenge, and institute their discoveries. Providing nursing students with easy-to-use, free internet tools for reaching the first step in this process (i.e., gaining access to materials and peers) has been addressed by the proliferation of communication technologies available to any user with an internet connection. Beyond the gadgetry, with the development of new strategies, practices, applications, and resources in technology comes the need for instructional strategies that not only appeal to this newer generation of students but also enhance learning. Such strategies, when coupled with easily accessible and highly functional tools, encourage nursing students to see beyond the right answer and seek out information that encourages them in developing approaches to issues and resolutions for problems. According to Hughes (2022), “Make sure that your strategies are agile, customizable, and ready for the momentum of Generation Z” (para. 33).

Digital Books (eBooks)

There is an unmistakable trend toward the development and use of digital books. It is clear that the ability to create eBooks that use the interactional capabilities brings more to the learning experience than just replicating a print-based text as an eBook. Affordability is one key advantage of eBooks. The possibility also exists of embedding content into the eBook, which could provide a link to a multimedia video or a website. The good news is that the quality of eTextbooks is greatly improving. It is a trend worth following in the future, especially because “Gen Z might not be picking up a novel, but they are reading content on the internet, and they're finding themselves represented in formats like manga” (Jensen, 2019, para. 22). These learners are used to collaborating and interacting digitally and are looking for the same in their learning episodes.

Webcasts and Webinars

A webcast is a broadcast of a presentation delivered by way of the web. Webcasts offer great potential for helping students and faculty to engage with both information and one another globally by tapping into students' multiple intelligences to enable them to access what they need. Because of the growing ease of producing streaming video and subsequently delivering it via larger bandwidth, webcasts have grown in popularity and are especially favored by programs that feature distance education components. Although some institutions create their own webcast delivery system, most users rely on a few standard providers, which in turn present the webcast online. Although these presentations are often delivered live, which allows audience members to participate in the broadcast, many instructors use webcasts as an access point for prerecorded archives of lectures and presentations by experts whom their students would not otherwise have the opportunity to see or hear. Studies show that students enthusiastically embrace webcast technology by accessing archived presentations more repeatedly than traditionally filmed sessions of guest lecturers; this dynamic level of engagement aids learners in better grasping the subject matter, especially when they are prebriefed and understand the learning outcomes before they view the webcast.

A webinar is a web-based seminar that uses web conferencing software, which allows educators to share their computer screen and files and interact with their students. Some webinar services allow for interactive sessions in which the audience can engage with the presenter. According to Waas (2019), “interacting with the hosts leads to higher engagement and longer total time spent on the webinar” (para. 11). Webinars are typically delivered live but can be recorded. In this geographically dispersed online world of learners, webinars provide another avenue for sharing and collaborating.

There is a key difference between webcasts and webinars. Webcasts present material to the audience with limited or no interactivity. By comparison, webinars are generally live, interactive, educational sessions. Both of these venues provide access to the educator and, depending on the level of interactivity, to other learners.

Searching

One of the most common and proliferative search tools in technology today is the wiki. Wikis are websites or hypertext document collections that allow users to edit and add content in an open-ended forum. The appeal of (and objection to) wikis resides in their ability to let anyone with an interest and an internet connection participate in a once-exclusive community of knowledge creators and seekers. As an environment that encourages practice and learning, wikis support learning communities in which learners collaborate online or virtually. Higher education has evolved from a place of straightforward knowledge transmission to a place where one strives to become a member of an expert community, and wikis promise to create opportunities for individuals to participate in this community in heretofore untapped ways.

The most objectionable aspects of wikis are their lack of organizing principle (many are organized alphabetically) and the ability for anyone to edit entries, the latter of which creates new intellectual property rights challenges. Wikipedia, for example, is the best-known wiki project on the web; it is an online encyclopedia of sorts whose open access policy regarding its content keeps educators and professionals wary of inaccurate information to be found there. Wikipedia works well as an initial source of information on a topic or as a quick overview reference, but we must educate our learners that it should not be relied on as a sole source of information. For more information on the appropriate use of Wikipedia, see this online tutorial: https://libguides.cmich.edu/web_research/wikipedia.

Instant Messaging

Instant messaging, one of many collaborative web chat tools available to any user with a computer and internet access, continues to establish itself as a working, useful tool for informatics learning by providing instant access to and communication among people, information, and technology. Although some instant message (IM) services provide voice and video messages, all instant messaging (IM'ing) clients provide text in real time, which allows users to interact in the form of an on-screen conversation through a technology that is free, already quite popular with users, and web based; does not require additional hardware or software; and has a very low learning curve for those few to whom it is unfamiliar. Beyond having a real-time conversation, IM'ing an individual allows the user to share links, pictures, and files. When learners are logged on, this kind of easy accessibility allows them to collaborate, seek real-time help from professors or librarians, and engage others working on the same learning content.

Chats and Online Discussions (Blogs)

Real-time chats occur all over the internet, at every hour of every day. The best-known chat tools are instant messenger clients, but chatting also refers to real-time discussion venues in which users meet in virtual chat rooms to engage in conversations by posting messages. Chat rooms provide a comfortable, recognizable way of communicating for Net Generation students used to surfing the web and interacting online. In a chat, students can meet, discuss, and engage one another over any topic. Chats take various forms, the most complex of which involve highly evolved virtual communities in which users step into various rooms where they interact with other individuals who are in the room at the same time. Initially, the exclusive purview of gamers or hard-core programmers who created private online communities, chat rooms now exist for a wide variety of topics and interests.

Web logs, also known as blogs, have emerged as low-investment and easy-to-use writing tools. Their very setup and appearance enhance health professionals' communication, writing, reading, information-gathering, and collaboration skills. Blogs are a kind of online journal created by individuals who then invite comments from visitors to that web space. Compared to technically complex online projects, such as tutorials and various multimedia, blogs are immediate, free to set up and access with an internet connection, and easily negotiable by even the technically ambivalent. They are especially useful for study groups interested in reflecting on material and evaluating ideas in a collective, collaborative way, since blogs present a built-in discussion area to the user. Blogs are a great way for students and professionals to reflect on and share clinical experiences and questions with one another. It is important, however, to be mindful of protecting private health information and to share within the confines of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidelines.

Electronic Mailing Lists

One low-investment information-gathering tool for use by nursing professionals is membership in an electronic mailing list. These electronic discussion groups use email to communicate and promote communication and collaboration with others interested in a particular field of study since they have very few requirements for participating, usually just a free subscription and email capability. Such lists are available on any subject, but most lists share common features, such as the need to subscribe and then log on to participate. The moderators of an electronic mailing list have specific instructions on how to post messages and set subscription controls. Posting information means that when a user replies to a topic thread, they generally have sent information to every member of the list. Like other technologies, the capabilities of electronic mailing lists continue to change and expand and provide ongoing viability for use in nursing education.

Portals

Like electronic mailing lists in the way they deliver specific information to one's email, a portal organizes information from web pages into simple menus so that users can choose what content they want to view and how to view it. For example, WebMD is one of the most popular and best-known portals, which allows users to create accounts, bookmark their favorite information, and sign up for email notifications. Portals, like most web technologies, require an internet connection and a free subscription, which allows the user to log on.

Podcasts: Audiopods and Videopods or Videocasts

A podcast is an audio recording linked to the web that is then downloaded to an MP3 or MP4 player, a smartphone, or a computer through which the listener can then access the recording or video. An outgrowth of the Apple iPod market, podcasts are developed and delivered by way of the internet and require minimal investment-namely, a microphone, an internet connection, and (often free) editing software.

Beyond possibilities for global accessibility to whatever information the user may record, podcasts allow for automatic updates in the form of a really simple syndication (RSS) (also known as a resource description framework [RDF] site summary) feed, which lets subscribers receive an automatic notification whenever a podcast is updated. Refer to Box 19-2 for more information.

| Box 19-2 Podcasts |

|---|

| Jackie Ritzko

A basic web search using the search term “free nursing podcast” produced over 1 million hits on one search engine. But what does this information mean in the context of nursing informatics? The implication is that there are many resources on the internet that involve podcasts with a nursing focus. How these sites might be of use to a professional in the nursing field is the focus of this feature. Before any discussion of the educational uses of a technology tool can take place, however, there needs to be an understanding of the hardware, software, training, and support that are required to use the tool as well as the history of the development of the tool.

Podcast is a term coined from the words iPod and broadcast. iPod is the name given to a family of portable MP3 players from Apple. MP3 is a common file format for electronic audio files. Audio files-in particular, MP3 files-can contain verbal speech, music, or a combination of both. MP3 files can be listened to using an MP3 player. MP3 players can be portable devices, such as the iPod, or simply software that is installed and used on a computer, tablet, or smartphone. Thus, a podcast is simply an MP3 file that can be played on an MP3 player. Broadcast, in its simplest usage, refers to the ability to send out. In terms of podcasts, broadcasting is the ability to share MP3 files in such a way that the files are delivered to the user, through a subscription, whenever new versions are available. This ability to share and access the most up-to-date resources is a great advantage, especially for the educational community.

The discussion now turns to the function of podcasts, ranging from the more basic to the more advanced functions: finding, listening to, creating, and sharing podcasts. Finding podcasts at a minimal level requires only an internet connection and a web browser. As noted earlier, a basic web search for the term “free nursing podcast” produced many sites. Performing a basic web search, however, may provide a user with only limited search capabilities. An MP3 aggregator is a program that can facilitate the process of finding, subscribing to, and downloading podcasts. One popular aggregator is Apple's iTunes, which is a free program available as a download at www.apple.com/itunes. Although iTunes is widely used, it is not the only program of this type. A program such as iTunes gives the user the ability to search for podcasts based on many criteria, including category, author, or title. The iTunes program provides access to audio downloads that may be either songs or podcasts. In both cases, users may find downloads that are free and those that require payment.

Because podcasts are largely MP3 audio files (Advanced Audio Coding [AAC] is a newer format but is not as widely used), an MP3 player is needed to listen to a podcast. As noted, listening to a podcast can be done on a smartphone, a computer with an MP3 player, or a portable MP3 player. Podcasts can be downloaded in two ways: manually or by subscribing to a podcast. In the case of a subscription, once a new track is added to the podcast, iTunes automatically delivers it to a computer. Continuing to use iTunes as an example, once a podcast is found, it can also be manually downloaded from iTunes to a computer. Once on the computer, it can be listened to or transferred to a portable device or accessed via a tablet or smartphone.

Users may also choose to produce or record podcasts. Typically, as with most technology solutions, hardware and software requirements must be met to create podcasts. The hardware for recording a podcast can vary. In a stationary setup, a microphone can be connected to a desktop or laptop computer. Stand-alone audio recorders can also record podcasts, and some MP3 players contain built-in recorders. Free recording software is available for most computer platforms.

Sometimes a podcast is created for the sole use of the creator. More often, however, a podcast is created with the intention of it being shared with and listened to by others. Podcasts can be stored on web servers for distribution and shared via tools such as iTunes. Within iTunes, for example, educational institutions are able to host podcasts in the area known as iTunes U.

Podcasts have many uses in education in general and in nursing education in particular. Informal learning can take place when a nursing student listens to nursing podcasts. Listening to or creating podcasts may be a formal class assignment, which provides new ways to interact with course material.

Short discussions of what is new in the field may appear as podcasts on the internet, in particular on news and research sites. Learners may rely on the portability of MP3 players to take learning with them on the road. Commuters, walkers, and joggers are often seen listening to MP3 players. Because creating podcasts is relatively easy and inexpensive, such presentations can be produced by students as review files for common terms or used as ways for students to self-assess their ability to discuss topics. The uses of podcasts from an educational perspective are limitless.

Bringing the discussion of podcasts back to the Foundation of Knowledge model, for each task or process in the model, one can see how podcasts fit with that concept. Podcasts can be used to acquire new knowledge from sources on the web. Listening to podcasts provides learners with another tool for learning in addition to readings and lectures, thereby addressing a wider audience whose members have varying learning styles. Because podcast creation is simple and inexpensive, podcasts are an ideal way to generate and disseminate knowledge.

|

Audiopods

Audiopod is a term used to describe a traditional, or audio-based, podcast. Participating in podcasting can exercise not just basic technology skills but also writing, editing, and speaking skills. An excellent exercise for learners could be in the creation of the audiopod, using critical thinking to write the script and deliver the information. The technology itself allows global access to information by faculty, teachers, and learners anywhere, anytime. Both faculty and students can create audiopods with little difficulty to share additional class materials, updates, and even entire lectures.

Videopods or Videocasts

Like an audiopod in setup and accessibility, a videopod is a podcast that provides video in addition to audio functionality. Faculty might use videopods to demonstrate concepts and skills or even interview experts in the field and assess student progress.

Multimedia

As technologically savvy students continue to demand accessible, interactive learning tools to keep them engaged, an increasing number of LMSs are incorporating or interfacing with multimedia tools that permit videos or other media to be embedded so that interactive exercises can be generated using the media. They interface with applications such as those that will upload a video and generate a script from the video so that both can be embedded into the LMS for the learners to view. The term multimedia refers to a computer-based technology that incorporates traditional forms of communication to create a seamless and interactive learning environment, such as interactive tutorials, streaming video, and problem-solving programs. With the new user-friendly advances in multimedia creation, faculty members are able to add such innovations as simulations and virtual reality to their healthcare training, providing a way for students to learn procedural skills, such as insertion of needles and physical assessment, without any risks to an actual patient.

Research suggests that the seeing, hearing, doing, and interacting afforded by multimedia facilitates learning retention, with multimedia being at least as effective as traditional instruction but offering the benefit of greater learner satisfaction. As always, the faculty must design or lead the development using appropriate pedagogy as they intentionally combine the text, graphics, video, animation, and sound of their multimedia product. Some schools of nursing have instructional designers and multimedia developers on staff to assist nursing faculty with the development of multimedia to support learning.

Beyond providing a flexible method of delivery for instructional information, multimedia promise to accommodate different learning styles and motivate students by requiring them to analyze evidence in ways that require higher-order thinking and problem-solving skills.

Box 19-3 provides an overview of the capabilities of smartphones and their use in education.

| Box 19-3 Smartphones and Other Smart Devices in Nursing Education |

|---|

| Smartphones are another tool for the educational arena. As Yu (2012) stated, “Smart phone technology, with its pervasive acceptance and powerful functionality, is inevitably changing peoples' behaviors” (para. 6). According to Georgiev (2023), the following are the current statistics concerning smartphone usage: Worldwide 2.71 billion people use smartphones, 81% of Americans own a smartphone, more than 285 million people in the United States with 94% of people aged 18 to 29 and 98% of Gen Zs. Nursing educators' use of a technology, such as smartphones, not only affects the learning episode but also influences how students are prepared to embrace and use technologies appropriately. They want their students to remain competitive in a highly technologically dependent world. Nursing is a data- and information-driven profession, and nurses must rely on technology to provide the data and information necessary to provide safe and high-quality care to their patients.

If students have smartphones, nursing educators can share text; graphics, such as PowerPoint presentations; podcasts; and other audio and video media with them prior to the learning episode. When all students have access to the same information, the dialogue and topical discussion centered on that information are enhanced. Nursing educators can use smartphones to distribute announcements, reminders, and even pertinent notes that the students need. Students can also be polled using these devices. Smartphones can even replace huge textbooks with electronic files. Smart devices and their calendars and messaging features help both educators and students organize their lives and keep their hectic schedules straight. The use of smart technology can facilitate interactions around the world. Students can consult with other students and experts from anywhere on the globe. As this brief list of applications suggests, educators continually think of ways in which to incorporate smartphones into their learning episodes.

In conclusion, we would like to leave you thinking about a money-saving alternative for many schools. Instead of requiring a laptop computer, what if your school required every student to have a smartphone? Could we replace the expensive computer labs on our campuses while better connecting our online and blended students to their educational milieu?

|

Promoting Active and Collaborative Learning ⬆ ⬇

Because of the shift within the teaching-learning context from the individual seeking answers to the group trying to construct new knowledge from available information, the most effective learning solutions require new digital communication skills, new paradigms, new pedagogies, and new practices. A collaborative, student-centered approach uses the best tenets of inductive teaching by imposing more responsibility on students for their own learning than is assumed in the traditional lecture-based deductive approach. These constructivist methods are built on the widely accepted principle that students are constantly constructing their own realities rather than simply absorbing versions presented by their teachers. Collaborative methods often involve students' discussion of questions and in-class problem-solving, with much of the work (in and out of class) done by students in groups rather than individually (Felder & Prince, 2007).

Johnson and Johnson (1990) identified five significant elements for successful collaborative learning that are still pertinent today:

- Face-to-face interaction between students, allowing them to build on one another's strengths

- Mutual learning goals, which in turn prompt students to exhibit positive interdependence rather than individualized competition

- Equal participation in the work process and personal accountability for the work one contributes

- Regular debriefing sessions as a group after meetings or presentations, during which time feedback is shared and observations are analyzed

- Use of cooperative group process skills learned in the classroom

Although collaborative learning relies heavily on student investment and participation, institutions must ultimately create the best physical, electronic, and immersive settings in which collaboration is encouraged. Creating these settings can be achieved with a sound educational and technological infrastructure, reliance on proven working models, adaptable physical spaces, and even pedagogical support in the form of preceptors or mentors.

Especially useful for nursing students is the collaborative fieldwork model in which two or more students share a clinical setting and the same fieldwork educator. In this model, learning happens in a reciprocal fashion, with students constructing knowledge by watching each other and exchanging ideas. The most effective fieldwork experiences are highly structured with clear outlines of responsibilities, duties, and expectations to ensure that the experience matches the learner's expectations. The sharing of perspectives and viewpoints results in the generation of new knowledge and the restructuring or reorganization of existing knowledge. All activities performed by students, such as conducting evaluations, are done jointly so that peers provide each other with objective feedback, which eventually leads to increased self-confidence (Costa, 2007).

Libraries have also begun to recognize their role in students' success with and predisposition toward collaborative learning by creating redesigned spaces that reflect students' need to huddle in small groups; sit closely together without barriers; chat about their work; and view digital information without physical hindrances, such as carrels or work stalls. A leader in this movement has been Indiana State University, whose information commons features completely overhauled furniture, software, monitors, processing power, and wireless access to the university's network. Students can now collect as a group at kidney-shaped tables; better see the information loaded on the flat-screen monitors; make use of brainstorming, design, and planning software; and discuss their work in a chat-friendly zone. Some faculty members have even scheduled classes at the learning stations, and students, including those in nursing, have responded enthusiastically to the evolved space (Gabbard et al., 2007).

In addition to adaptable physical spaces that encourage discussion and group work, students require a supportive infrastructure that provides the essential elements for successful research and scholarship. These elements include professional development support in the form of workshops that help students acquire or refresh skill sets; presentation opportunities; and hardware, software, and resource support. One such example involves the participation by nursing students at the University of Texas Medical Branch School of Nursing in the Scholarly Talk About Research Series (STARS), in which students and faculty give presentations of their work before presenting those materials at professional conferences (Froman et al., 2003), thereby eliciting collegial feedback, collaborative troubleshooting, and shared research ideas. Imagine how powerful such a process would be in a cross-discipline healthcare education school.

Simply adopting a collaborative, inductive method of learning, however, will not necessarily lead to better learning and more satisfied students. As with any form of instruction, collaborative teaching methods need skilled and careful implementation. Because students can be resistant to instruction that makes them more responsible for their own learning, those who attempt to implement an inductive learning method should adhere to best practices, such as providing adequate scaffolding, which is extensive support and guidance when students are first introduced to the method and gradual withdrawal of that support as students gain more experience and confidence in its use (Felder & Prince, 2007).

Nursing preceptors and mentors, for example, can provide this kind of scaffolded support as clinically active role models (Armitage & Burnard, 1991) and problem-solving advocates and collaborators (Gagen & Bowie, 2005). As individuals who are primarily concerned with the teaching and learning aspects of the relationship, preceptors help students learn by acting as clinical practitioner role models from whom the students can copy appropriate skills and behaviors. Kramer (1974) introduced the concept of nurse preceptor to address the theory and practice gap, which is the difference between what is taught in class and what actually happens in nursing practice. Preceptors enhance clinical competence through direct role modeling, which is especially valuable in a field where competence and clinical ability are paramount (Armitage & Burnard, 1991). Mentors, who are similar to preceptors, provide equally valuable assistance to nursing students in the form of a facilitator. Mentors are most often used in nursing and education to support new professionals who are trying to fulfill the rigors of a new position while negotiating the stress inherent to a new environment (Gagen & Bowie, 2005). According to Jokelainen et al. (2011), “student mentoring in nursing clinical placements integrates environmental, collegial, pedagogical and clinical attributes” (para. 6). Mentors tend to address student needs through open conversation, student advocacy, feedback on student progress, facilitation, teaching, and general support (Neary, 2000). Artificial intelligence (AI) agents are also available to students to support them throughout their educational programming.