AUTHORS: Amanda Jones, MD and Anthony Sciscione, DO

A pituitary adenoma is a benign neoplasm of the anterior lobe of the pituitary. Pituitary adenomas may cause symptoms, either by excess secretion of hormones or by a local mass effect as the tumor impinges on other nearby structures (e.g., the optic chiasm, hypothalamus, or pituitary stalk). Pituitary adenomas are classified by their size, function, and features that characterize their appearance. Microadenomas are <10 mm in size, macroadenomas are ≥10 mm in size, and giant adenomas are ≥40 mm in size. Depending on the anterior pituitary cell type of origin of the tumor, a pituitary adenoma may be secretory or nonsecretory.

- Nonsecretory pituitary adenomas are those in which the neoplasm is a space-occupying lesion whose secretory products do not cause a specific disease state.

- Secretory pituitary adenomas (Table 1) can cause endocrine manifestations related to the hormone they are secreting.

TABLE 1 Types of Pituitary Adenomas Based on Hormones Secreted

| Adenoma Type | Hormones | Possible Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| Somatotroph adenoma | Growth hormone | Gigantism, acromegaly |

| Mammosomatotroph | Growth hormone + prolactin | Gigantism or acromegaly along with galactorrhea or amenorrhea |

| Corticotroph adenoma | Adrenocorticotropic hormone | Cushing disease |

| Lactotroph adenoma∗ | Prolactin | Women: Reproductive or sexual dysfunction, galactorrhea, amenorrhea, ovulatory disorders Men: Erectile dysfunction, decreased libido |

| Gonadotroph adenoma | Follicle-stimulating hormone or luteinizing hormone | Most are clinically silent and usually present due to mass effect |

| Thyrotroph adenoma | Thyroid-stimulating hormone | Hyperthyroidism |

| Plurihormonal | Growth hormone, prolactin, thyroid-stimulating hormone, various hormonal combinations | Most are clinically silent |

| Null cell adenoma | No hormones | No symptoms of hormonal excess, usually present due to mass effect |

∗Most common type of adenoma (∼40% of cases).

From Jankovic J et al: Bradley and Daroff’s neurology in clinical practice, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

Endocrine manifestations of secretory adenomas include:

- Acromegaly, a disease state characterized by a pituitary adenoma with somatotroph cell origin that secretes growth hormone (GH); notably, a significant majority of somatotroph adenomas are clinically silent

- Galactorrhea, which is the result of a prolactinoma with lactotroph cell origin that secretes prolactin (PRL)

- Cushing disease, a disease state of hypersecretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) due to corticotroph cell origin of the tumor

- Hyperthyroidism due to a thyrotropin-secreting pituitary adenoma, due to a thyrotroph cell origin which secretes primarily thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH); notably, thyrotroph adenomas may also present as nonsecretory sellar masses

| ||||||||

- Pituitary adenomas: Up to 15% of all intracranial neoplasms; 3% to 27% at autopsy series. The prevalence of pituitary adenomas has increased to 100 cases/100,000 over the past decades, likely as a result of enhanced awareness and improved diagnostic imaging and hormone assays. True prevalence is likely underestimated due to nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas going undiagnosed until they are large. There is a higher prevalence in females.

- Prolactinomas: Up to 20% in women with unexplained primary or secondary amenorrhea.

- GH-secreting pituitary adenoma: Prevalence of 3.3 to 13.7 cases/100,000. They account for 8% to 16% of pituitary tumors and are most common in men over age 50.

- Thyrotropin-secreting pituitary adenoma: 1% of pituitary adenomas with a slight female:male predominance of 1.7:1.

- Corticotropin-secreting pituitary adenomas: Female:male predominance of 8:1 but overall uncommon diagnosis, accounting for 2% to 6% of adenomas.

Most individuals remain asymptomatic.

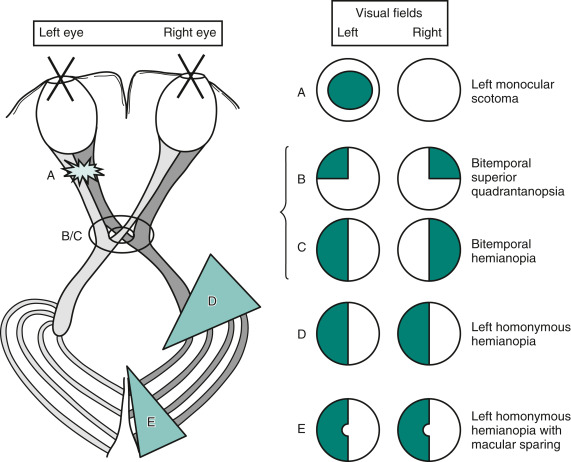

All sellar masses can cause visual defects by compression of the optic chiasm (bitemporal hemianopsia (Fig. E1) or headaches.

Lesions at Specific Sites Produce Characteristic Visual Field Defects. Conversely, the Defects Indicate the Lesion's Location and Give Hints to its Etiology and Expected Associated Findings. (A) Optic Nerve Lesions Typically Produce an Ipsilateral Scotoma. (B) Optic Chiasm Lesions from below, When Small (Smaller Ring), Cause a Superior Bitemporal Quadrantanopsia. (C) When Large (Larger Ring), Optic Chiasm Lesions Result in Bitemporal Hemianopia. (D) Cerebral Lesions that Disrupt the Optic Tract Produce Contralateral Homonymous Hemianopia. (E) Lesions that Interfere with the Occipital Cortex Also Yield Contralateral Homonymous Hemianopia, Sometimes with Macular Sparing. Although the Determination of Visual Fields Serves as a Highly Reliable Sign of Localized Neurologic Disease, Their Graphic Representation is One of Clinical Neurology’s Most Confusing Exercises. In the Standard Manner, These Sketches Portray Visual Field Defects as Solid or Crosshatched Areas from the Patient’s Perspective. for Example, the Sketch of the Left Homonymous Hemianopia (D) Portrays the Abnormal Areas on the Left Side of Each Circle-as When the Patient Looks at the Paper. The Sketch of Cerebral Optic Tract Pathways Portrays the Tracts as Though a Picture Had Been Taken of the Patient’s Brain from above. In Contrast, Cts and Mris Traditionally Show the Left Side of the Brain on the Right Side of the Image. Medical Illustrations Should Include a Notation to Orient the Reader.

From Kaufman DM et al: Kaufman’s clinical neurology for psychiatrists, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2023, Elsevier.

- Females:

- Galactorrhea

- Amenorrhea

- Oligomenorrhea with anovulation

- Infertility

- Estrogen deficiency and associated osteopenia

- Decreased vaginal lubrication

- Males:

- Large tumors more common as a result of delayed diagnosis

- Possible impotence, decreased libido, or hypogonadism

- Galactorrhea rare because males lack the estrogen-dependent breast growth and differentiation

- Usually large at the time of diagnosis

- Symptoms:

- Bitemporal hemianopsia as a result of compression of the optic chiasm

- Hypopituitarism from compression of the pituitary gland

- Hypogonadism in men and in premenopausal women

- Cranial nerve deficits caused by extension into the cavernous sinus

- Hydrocephalus from extension into the third ventricle, compressing the foramen of Monro

- Diabetes insipidus resulting from compression of the hypothalamus or pituitary stalk (a rare complication)