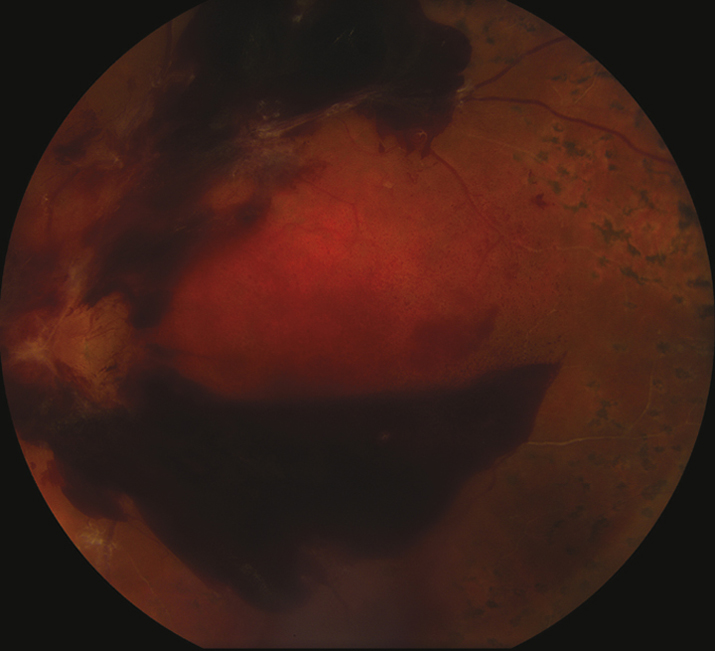

(See Figure 11.13.1.)

Critical

In severe VH, the red fundus reflex may be absent, and there may be limited or no view to the fundus. Red blood cells may be seen in the anterior vitreous (or anterior chamber). In mild VH, there may be a partially obscured view to the fundus. Chronic VH has a yellow ocher appearance from hemoglobin breakdown.

Other

A mild RAPD is possible in the setting of dense hemorrhage. Depending on the etiology, there may be other fundus abnormalities.