Diabetic Retinopathy Disease Severity Scale

- No apparent retinopathy.

- Mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR): Microaneurysms only.

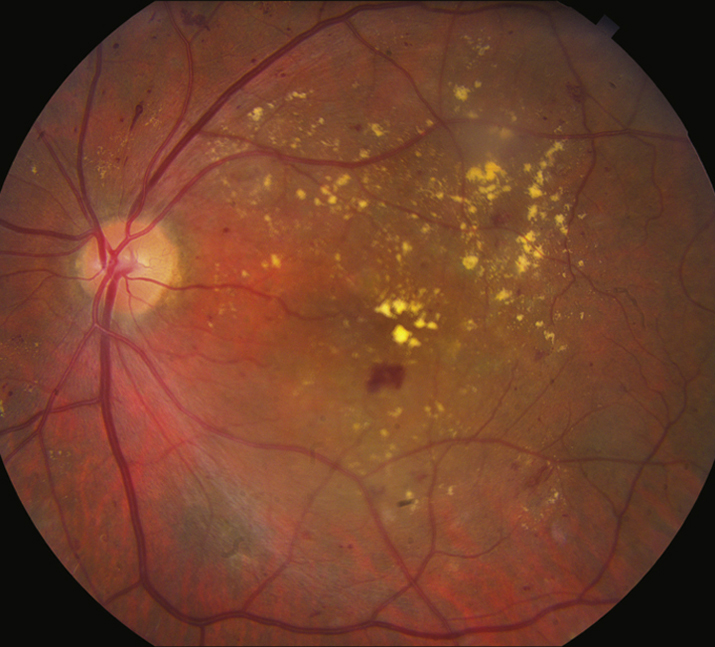

- Moderate NPDR: More than mild NPDR, but less than severe NPDR (see Figure 11.12.1). May have CWSs and venous beading.

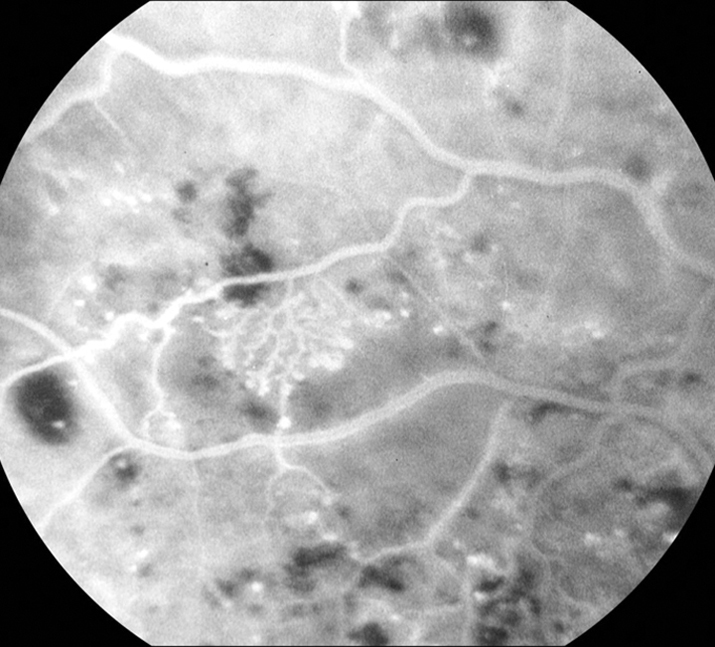

- Severe NPDR: Any of the following in the absence of PDR: Diffuse (traditionally >20) intraretinal hemorrhages in all four quadrants, two quadrants of venous beading, or one quadrant of prominent intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (see Figure 11.12.2).

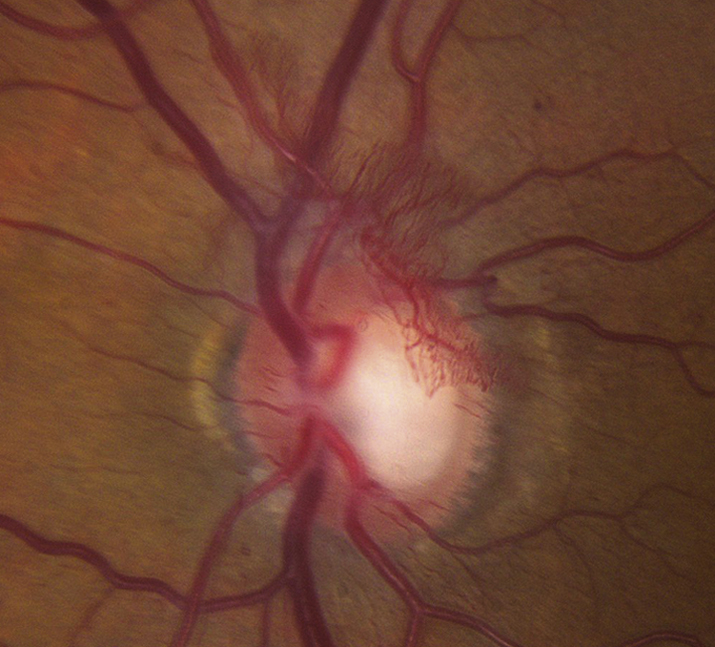

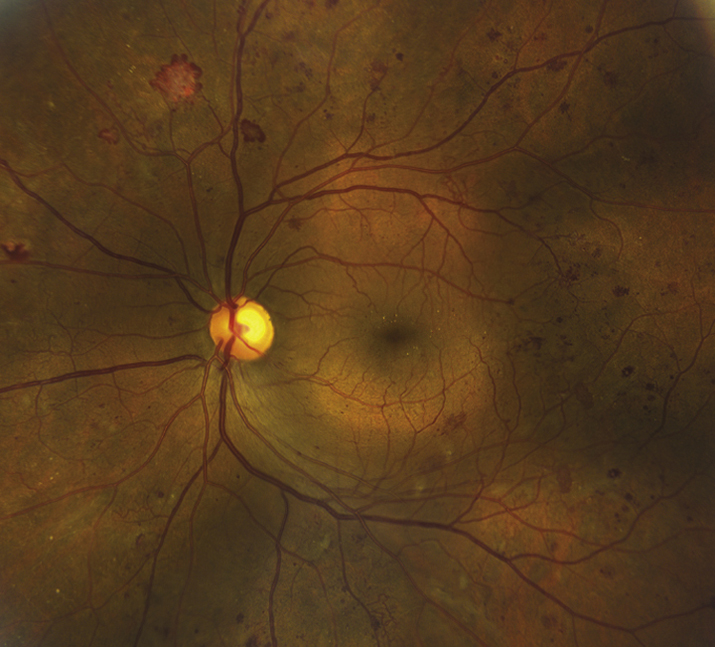

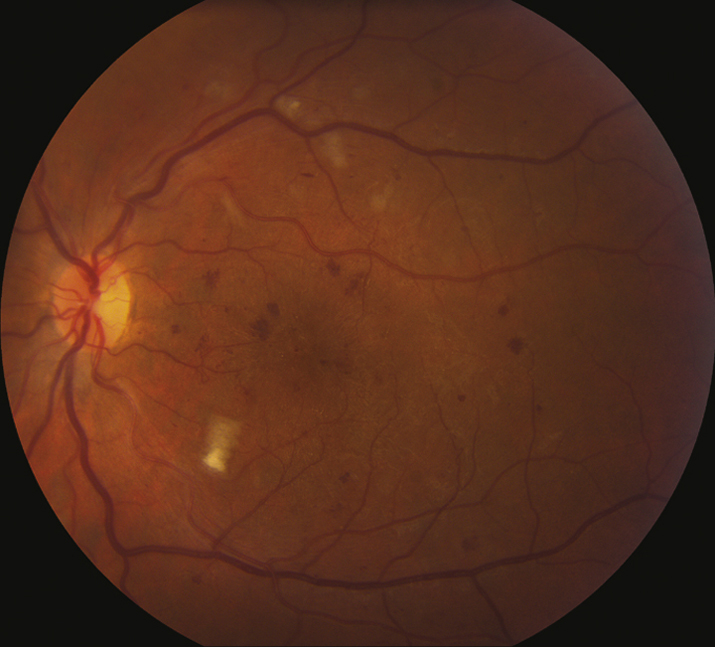

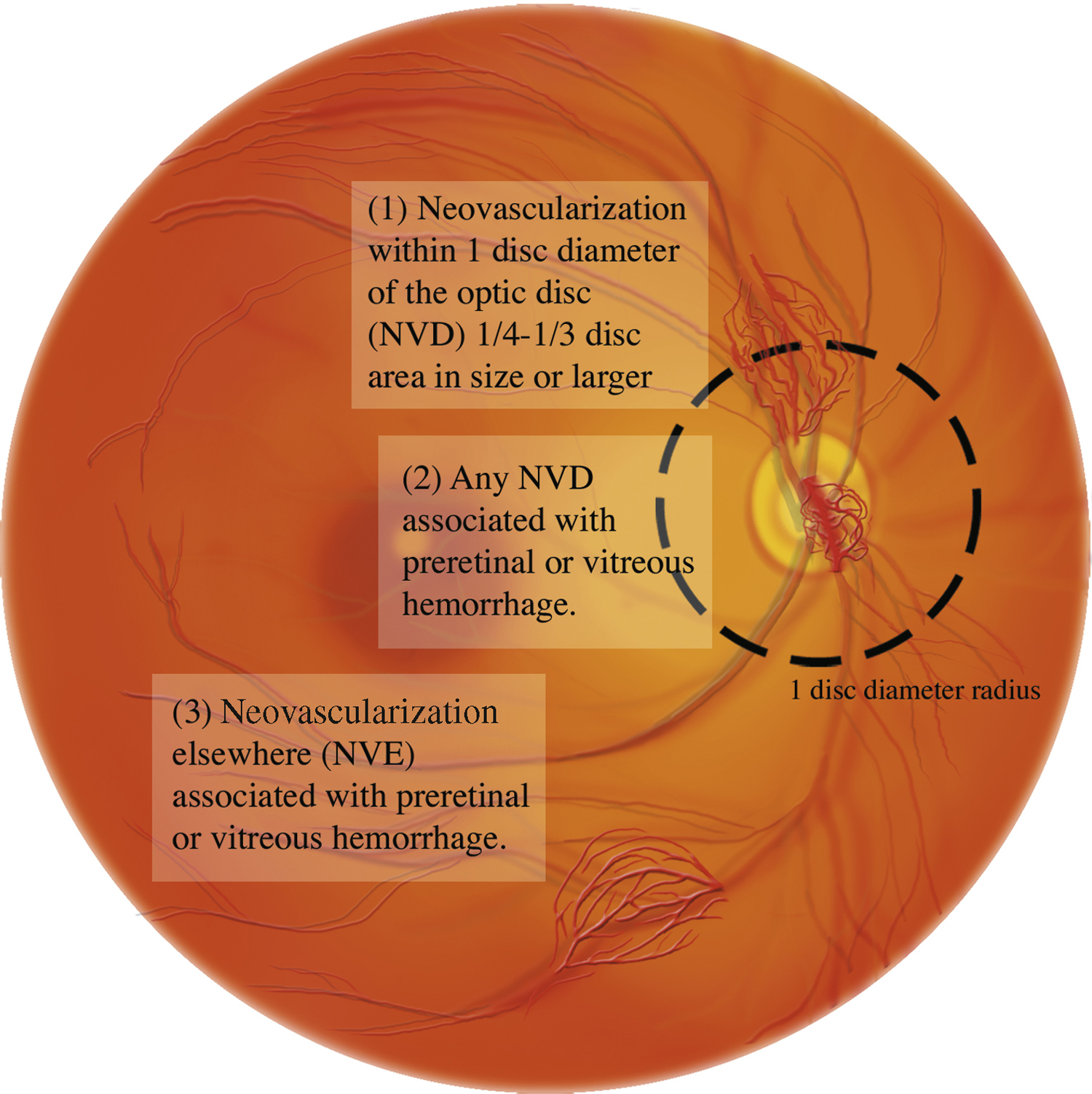

- PDR: Neovascularization of one or more of the following: iris, angle, optic disc, or elsewhere in retina; or vitreous/preretinal hemorrhage (see Figures 11.12.3 and 11.12.4).

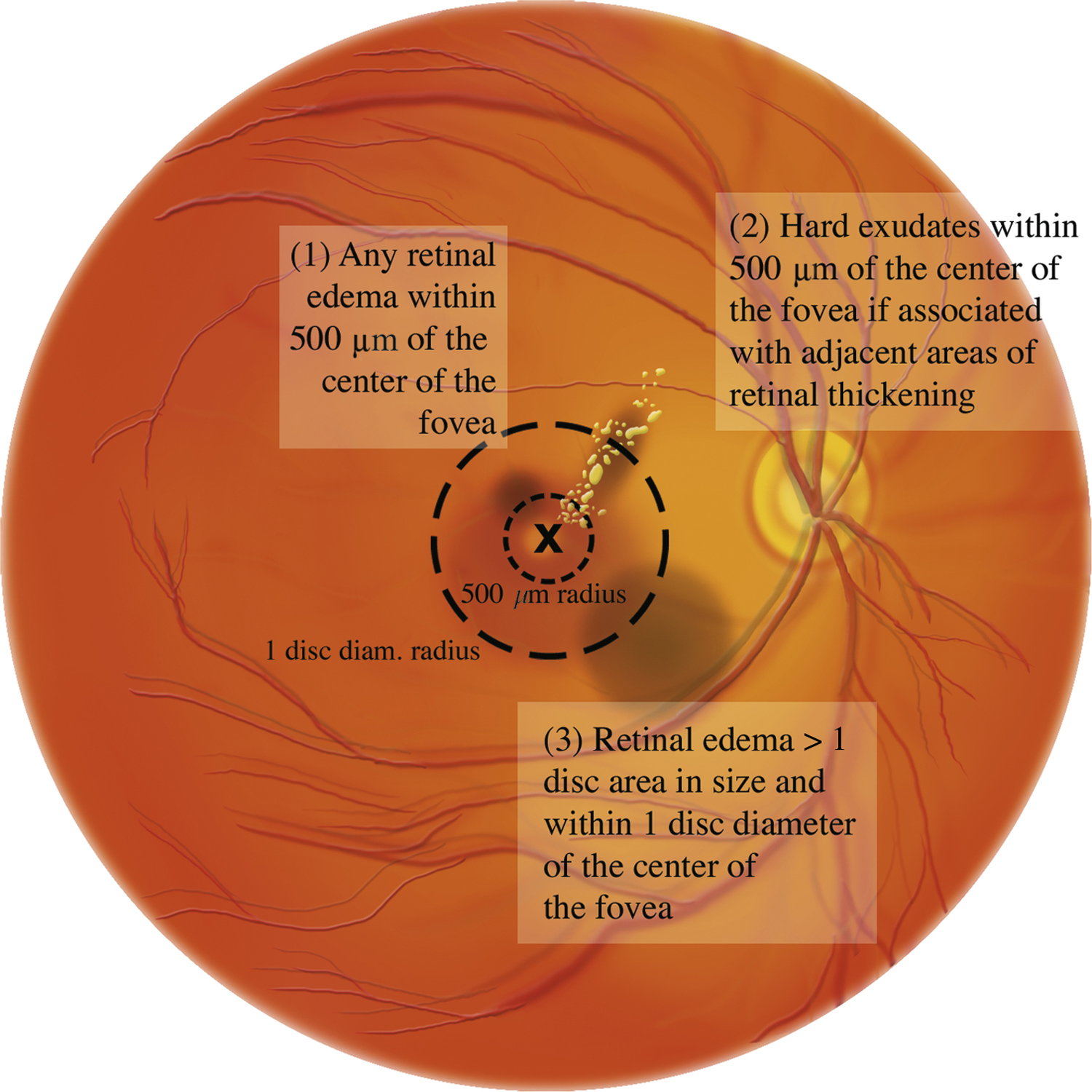

- Diabetic macular edema (DME): May be present in any of the stages listed above. DME affecting or threatening the fovea is an indication for treatment (see Figures 11.12.5 and 11.12.6).

Differential Diagnosis for Nonproliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

- CRVO: Optic disc swelling, veins are more dilated and tortuous, hard exudates and microaneurysms usually not found, hemorrhages are nearly always in the NFL (“splinter hemorrhages”). CRVO is generally unilateral and of more sudden onset. See 11.8, CENTRAL RETINAL VEIN OCCLUSION.

- BRVO: Hemorrhages are distributed along a vein and do not cross the horizontal raphe (midline). See 11.9, BRANCH RETINAL VEIN OCCLUSION.

- OIS: Hemorrhages mostly in the midperiphery and larger; exudates are absent. Usually accompanied by pain; mild anterior chamber reaction; corneal edema; episcleral vascular congestion; a mid-dilated, poorly reactive pupil; iris neovascularization. See 11.11, OCULAR ISCHEMIC SYNDROME/CAROTID OCCLUSIVE DISEASE.

- Hypertensive retinopathy: Hemorrhages fewer and typically flame-shaped, microaneurysms rare, and arteriolar narrowing present often with arteriovenous crossing changes (“AV nicking”). See 11.10, HYPERTENSIVE RETINOPATHY.

- Radiation retinopathy: Usually develops within a few years of radiation. Microaneurysms are rarely present. See 11.5, COTTON–WOOL SPOT.

Differential Diagnosis for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

- Neovascular complications of CRAO, CRVO, or BRVO: See specific sections.

- Sickle cell retinopathy: Peripheral retinal neovascularization. “Sea fans” of neovascularization present. See 11.20, SICKLE CELL RETINOPATHY (INCLUDING SICKLE CELL DISEASE, ANEMIA, AND TRAIT).

- Embolization from intravenous drug abuse (talc retinopathy): Peripheral retinal neovascularization in patient with history of intravenous drug abuse. Typically see talc particles in retinal vessels. See 11.33, CRYSTALLINE RETINOPATHY.

- Sarcoidosis: May have uveitis, exudates around veins (“candle-wax drippings”), NVE, or systemic findings. See 12.6, SARCOIDOSIS.

- Other inflammatory syndromes (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus).

- OIS: See 11.11, OCULAR ISCHEMIC SYNDROME/CAROTID OCCLUSIVE DISEASE.

- Radiation retinopathy: See above.

- Hypercoagulable states (e.g., antiphospholipid syndrome).