Unilateral or bilateral ocular pain, photophobia, and decreased vision. May have an insidious onset, especially in older patients with chronic disease. Systemic findings may include shortness of breath, parotid enlargement, fever, arthralgias, and rarely neurologic symptoms including cranial nerve palsy. Most common in the 20- to 50-year age group. Most common in African Americans and Scandinavians.

WorkupThe following are the tests that are obtained when sarcoidosis is suspected clinically. See 12.1, ANTERIOR UVEITIS (IRITIS/IRIDOCYCLITIS) and 12.3, POSTERIOR UVEITIS, for other uveitis workup.

- Chest radiography: May reveal bilateral and symmetric hilar adenopathy and/or infiltrates indicative of pulmonary fibrosis, but may be normal in many patients and a negative result does not rule out sarcoidosis. Chest CT is more sensitive but more expensive. In cases of unilateral or atypical lung disease, consider malignancy.

- Serum ACE: Elevated in 60% to 90% of patients with active sarcoidosis. Similar to chest radiography, a normal level does not rule out sarcoidosis, and elevation is not specific. HIV, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, and leprosy may also present with elevated ACE. Patients with underlying lung disease (e.g., COPD) or patients on oral steroids and/or ACE inhibitors may have falsely low ACE levels. ACE levels in children are less helpful in diagnosis.

- Tissue biopsy: Definitive diagnosis requires demonstration of noncaseating granulomatous inflammation. Obtain biopsy of accessible affected lesions, including lymph nodes or edges of skin plaques or nodules. Sarcoid granulomas are not present in erythema nodosum and these lesions should not be sampled. An acid-fast stain and a methenamine–silver stain may be performed to rule out tuberculosis and fungal infection. A nondirected conjunctival biopsy in the absence of visible lesions has a low yield and is not recommended. Indurated areas of tattooed skin with concurrent uveitis may suggest tattoo-associated uveitis; skin biopsy may show noncaseating granulomas while the chest X-ray (CXR) is normal.

- PPD or IGRA: Useful for differentiating tuberculosis from sarcoidosis when pulmonary findings are present. Up to 50% of sarcoidosis patients are anergic and have no response to PPD or controls.

- Other: Some authors recommend serum and urine calcium levels, liver function tests, and a serum lysozyme. A positive result on one of these tests in the absence of chest radiographic or other findings is usually not helpful in diagnosis. A serum lysozyme may be useful in children, in whom ACE levels are often normal.

If laboratory and chest radiographic studies suggest sarcoidosis or in the setting of a negative workup but a high clinical suspicion of the disease, the following tests should be considered:

- Chest CT is more sensitive than CXR.

- Whole-body gallium scan is sensitive for sarcoidosis. A “panda sign” indicates involvement of lacrimal, parotid, and submandibular glands. A “lambda sign” indicates involvement of bilateral hilar and right paratracheal lymph nodes. A positive gallium scan and an elevated ACE level are 73% sensitive and 100% specific for sarcoidosis. Cost and inconvenience are drawbacks.

- Referral to a pulmonologist for pulmonary function tests and transbronchial lung biopsy.

- The risks of an invasive diagnostic test or radiation exposure must be weighed against the impact the results will have on treatment.

Refer patients to an internist or pulmonologist for systemic evaluation and medical management. Consider early referral to a uveitis specialist in complicated cases. A poor visual outcome has been reported with posterior uveitis, glaucoma, delay in definitive treatment, or presence of macula-threatening conditions such as CME.

- Anterior uveitis:

- Cycloplegic (e.g., cyclopentolate 1% t.i.d. or atropine 1% b.i.d.).

- Topical steroid (e.g., prednisolone acetate 1% q1–6h).

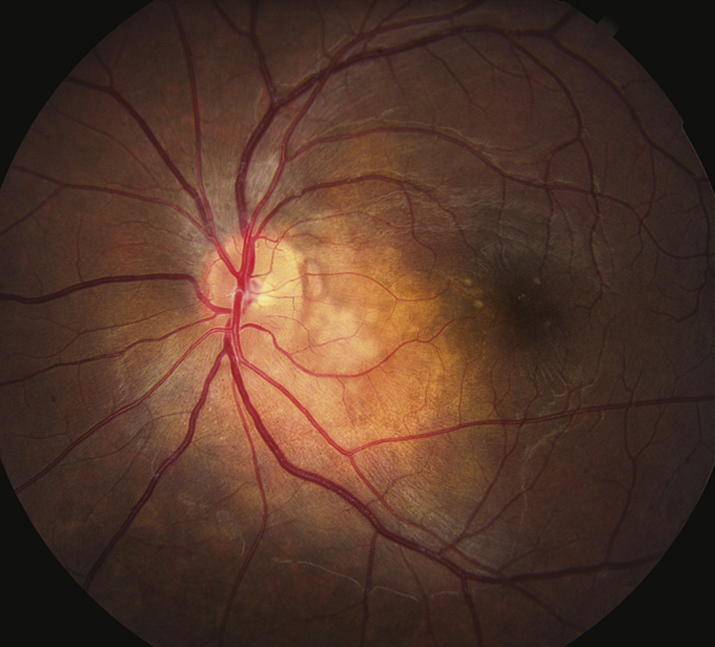

- Posterior uveitis:

- Supplement calcium with vitamin D (e.g., 600 mg with 400 iU) once or twice daily and consider a histamine type 2 receptor (H2) blocker (e.g., ranitidine 150 mg p.o. b.i.d.) or proton pump inhibitor (e.g., pantoprazole 40 mg daily).

- Periocular steroids (e.g., 0.5 to 1.0 mL injection of triamcinolone 40 mg/mL) may be considered instead of systemic steroids, especially in unilateral or asymmetric cases. Can repeat injection every 3 to 4 weeks. See Appendix 10, TECHNIQUE FOR RETROBULBAR/SUBTENON/SUBCONJUNCTIVAL INJECTIONS.

- Immunosuppressives (e.g., methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, and infliximab) have been used effectively as steroid-sparing agents. Decisions regarding therapy should be individualized given known side effect profiles of each regimen.

- CME: See 11.14, CYSTOID MACULAR EDEMA.

- Glaucoma: See 9.7, INFLAMMATORY OPEN ANGLE GLAUCOMA; 9.9, STEROID-RESPONSE GLAUCOMA; 9.4, ACUTE ANGLE CLOSURE GLAUCOMA; or 9.14, NEOVASCULAR GLAUCOMA, depending on the etiology of the glaucoma.

- Retinal neovascularization: May require panretinal photocoagulation.

- Orbital disease is managed with systemic steroids as described previously.

- Optic nerve granulomas require consultation with a neuro-ophthalmologist and treatment with systemic steroids.

- Pulmonary disease, facial nerve palsy, CNS disease, and renal disease require systemic steroids and management by an internist or neurologist.

NOTE: NOTE: |

Topical steroids alone are inadequate for the treatment of posterior uveitis. |