Pain, blurred vision, colored halos around lights, frontal headache, nausea, and vomiting.

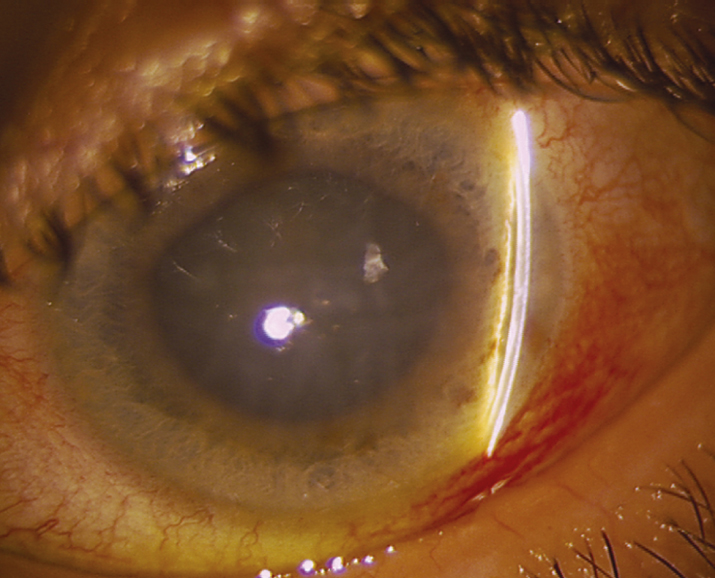

(See Figure 9.4.1.)

Critical

Closed angle in the involved eye, acutely increased IOP, and microcystic corneal edema. Narrow or occludable angle in the fellow eye if of primary etiology.

Other

Conjunctival injection; fixed, mid-dilated pupil.

9-4.1 Acute angle closure glaucoma with mid-dilated pupil, shallow anterior chamber, and corneal edema.

Depends on etiology of angle closure, severity, and duration of attack. Severe, permanent damage may occur within several hours. If visual acuity is hand motion or better, IOP reduction is usually urgent; therapeutic intervention should include all topical glaucoma medications, systemic (preferably intravenous) CAI, and in some cases intravenous osmotic agent (e.g., mannitol) as long as not contraindicated. Paracentesis with a 30-gauge needle on an open tuberculin syringe directed toward the 6 o’clock position will bring down the pressure immediately. See 9.14, NEOVASCULAR GLAUCOMA, 9.16, POSTOPERATIVE GLAUCOMA, and 9.17, AQUEOUS MISDIRECTION SYNDROME/MALIGNANT GLAUCOMA.

- Compression gonioscopy is essential to determine whether the trabecular blockage is reversible and may break an acute attack.

- Topical therapy with β-blocker ([e.g., timolol 0.5%] caution with asthma, COPD, and bradycardia), α2 agonist (e.g., brimonidine 0.1%), cholinergic agonist/miotic (pilocarpine 1%), prostaglandin analog (e.g., latanoprost 0.005%), and CAI (e.g., dorzolamide 2%) should be initiated immediately. In urgent cases, three rounds of these medications may be given, with each round being separated by 15 minutes.

- Topical steroid (e.g., prednisolone acetate 1%) may be useful in reducing corneal edema.

- Systemic CAI (e.g., acetazolamide 250 to 500 mg i.v. or two 250-mg tablets p.o. in one dose if unable to give i.v.) if reduction in IOP is urgent or if IOP is refractory to topical therapy. Do not use in sulfonamide-induced angle closure or sickle cell disease.

- Recheck the IOP in 1 hour. If IOP reduction is urgent or refractory to therapies listed above, repeat topical medications and give osmotic agent (e.g., mannitol 1 to 2 g/kg i.v. over 45 minutes [note: a 500 mL bag of mannitol 20% contains 100 g of mannitol]). Contraindicated in congestive heart failure, renal disease, and intracranial bleeding.

- When acute angle closure glaucoma is the result of:

- Phakic pupillary block or angle crowding: Historically, pilocarpine, 1% to 2%, every 15 minutes for two doses was recommended but has fallen out of favor by some physicians due to adverse effects such as headache, accommodative spasm, associated increased risk for uveitis and retinal detachment, and potential for miosis-induced angle closure.

- Aphakic or pseudophakic pupillary block or secondary closure of the angle: Do not use pilocarpine. Consider a mydriatic and a cycloplegic agent (e.g., cyclopentolate 1% to 2%, and phenylephrine 2.5% every 15 minutes for four doses) when laser or surgery cannot be performed because of corneal edema, inflammation, or both.

- Topiramate- or sulfonamide-induced secondary angle closure: Do not use CAIs in sulfonamide-induced angle closure. Immediately discontinue the inciting medication. Consider cycloplegia to induce posterior rotation of the ciliary body (e.g., atropine 1% b.i.d. or t.i.d.). Consider hospitalization and treatment with intravenous hyperosmotic agents and intravenous steroids (e.g., methylprednisolone 250 mg i.v. every 6 hours) for cases of markedly elevated IOP unresponsive to other treatments. Cases involving large ciliochoroidal or choroidal effusions may benefit from intravenous corticosteroids, as inflammation may play a role in their formation. Peripheral iridotomy (PI) or iridectomy and miotics are not indicated.

- In phacomorphic glaucoma, the lens should be removed as soon as the eye is quiet and the IOP controlled, if possible. See 9.12.4, PHACOMORPHIC GLAUCOMA.

- Address systemic problems such as pain and vomiting.

- For pupillary block (all forms) or primary angle crowding: If the IOP decreases significantly, definitive treatment with yttrium–aluminum–garnet (YAG) laser PI or surgical iridectomy is performed once the cornea is clear and the anterior chamber is quiet, typically 1 to 5 days after attack.

- Patients are discharged on a regimen of maintenance dose IOP-lowering drops and oral medications (described above), as well as topical steroids if inflamed. Close monitoring with IOP measurement each day is necessary immediately after an angle closure attack. Once the IOP has been reasonably reduced, follow-up frequency is guided by overall clinical response and stability. On occasion, topical steroids in addition to IOP-lowering medications are necessary for 4 to 7 days to increase the chance of successful iridotomy.

- For secondary angle closure: Treat the underlying problem. Consider argon laser gonioplasty to open the angle, particularly in plateau iris syndrome or nanophthalmos. Goniosynechiolysis can be performed for chronic angle closure of <6 months’ duration. Systemic steroids may be required to treat serous choroidal detachments secondary to inflammation.

NOTE: NOTE: |

Prior to initiation of systemic CAIs or osmotic agents, consider testing renal function. |

NOTE: NOTE: |

If the affected eye is too inflamed initially for laser PI, perform laser PI of the fellow eye first. An untreated fellow eye has a 40% to 80% chance of acute angle closure in 5 to 10 years. Repeated angle closure attacks with a patent PI may indicate plateau iris syndrome. See 9.13, PLATEAU IRIS. |

NOTE: NOTE: |

If IOP does not decrease after two courses of maximal medical therapy, a laser (YAG) PI should be considered if there is an adequate view of the iris. If IOP still does not decrease after more than one attempt at laser PI, then a laser iridoplasty, surgical PI, or cataract surgery is needed, depending on the etiology. A guarded filtration procedure should also be considered based on the severity of glaucoma and anticipated IOP control after definitive treatment. If IOP remains elevated and the angle remains closed despite a patent iridectomy, surgical treatment of chronic angle closure is indicated. |

After definitive treatment, patients are reevaluated in weeks to months initially and then less frequently. Visual fields and disc imaging are obtained for baseline purposes.

NOTE: NOTE: |

- Cardiovascular status and electrolyte balance must be considered when contemplating osmotic agents, CAIs, and β-blockers.

- The corneal appearance may worsen when the IOP decreases.

- Worsening vision or spontaneous arterial pulsations are signs of increasing urgency for pressure reduction.

- Since one-third to one-half of first-degree relatives may have occludable angles, patients should be counseled to alert relatives to the importance of screening.

- Angle closure glaucoma may be seen without an increased IOP. The diagnosis should be suspected in a patient who had episodes of pain and reduced acuity and is noted to have:

- An edematous, thickened cornea.

- Normal or markedly asymmetric pressure in both eyes.

- Shallow anterior chambers in both eyes.

- Occludable anterior chamber angle in the fellow eye.

|