DefinitionThree overlapping syndromes—essential iris atrophy, Chandler, and iris nevus (Cogan–Reese)—that share an abnormal corneal endothelial cell layer, which can grow across the anterior chamber angle. Secondary angle closure can result from contraction of this membrane.

Asymptomatic early. Later, the patient may note an irregular pupil or iris appearance, blurred vision, monocular diplopia, or pain if IOP increases or corneal edema develops. Usually unilateral and most common in patients 20 to 50 years of age. More common in women. Sporadic in presentation.

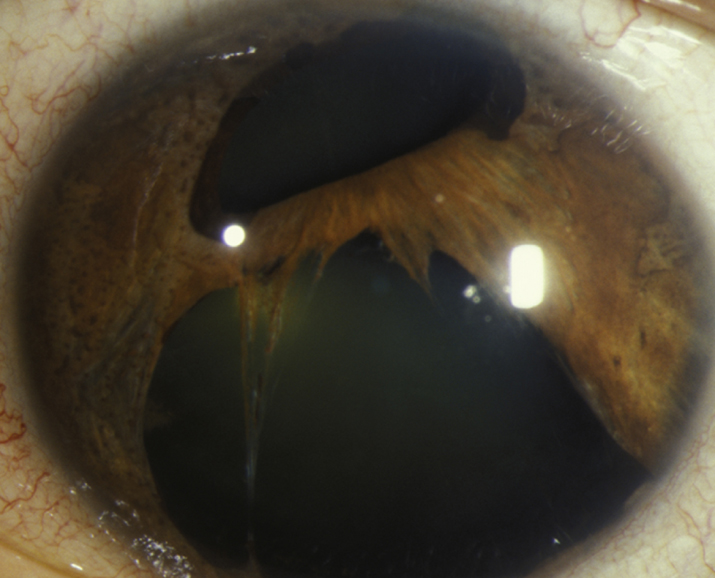

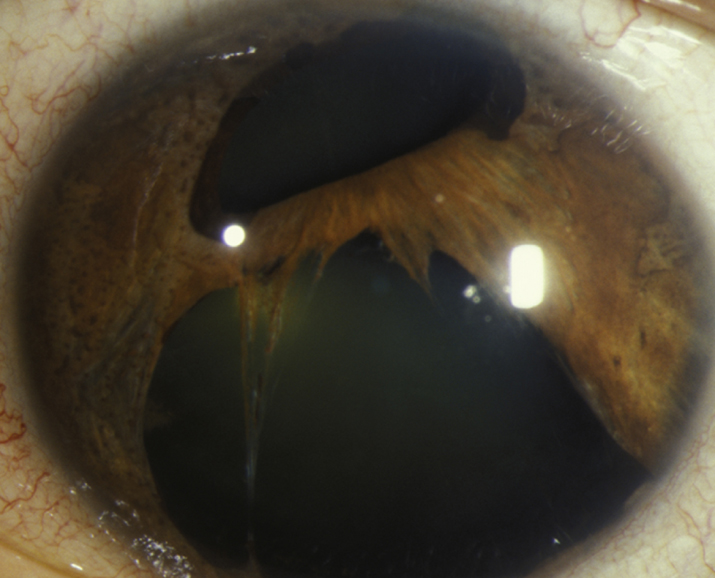

(See Figure 9.15.1.)

Critical

Corneal endothelial changes (fine, beaten-bronze appearance); microcystic corneal edema; localized, irregular, high PAS that often extend anterior to Schwalbe line; deep central anterior chamber; iris alterations as follows:

- Essential iris atrophy: Marked iris thinning leading to iris holes with displacement and distortion of the pupil (corectopia). Usually good prognosis.

- Chandler syndrome: Mild iris thinning and corectopia. The corneal and angle changes are most marked in this variant. Degree of findings is highly variable. Patients often have corneal edema even at normal IOP. Accounts for about 50% of ICE syndrome cases. Variable prognosis.

- Iris nevus/Cogan–Reese syndrome: Pigmented nodules (not true nevi) on the iris surface, variable iris atrophy. Similar changes may be seen in Chandler syndrome and essential iris atrophy, resulting from contraction of the membrane over the iris, constricting around small islands of iris tissue. Usually poor prognosis.

Other

Corneal edema, elevated IOP, optic nerve cupping, or visual field loss. Glaucoma is nearly always unilateral; occasional mild corneal changes may be seen in the fellow eye.

9-15.1 Essential iris atrophy.

No treatment is needed unless glaucoma or corneal edema is present, at which point one or more of the following treatments may be used:

- IOP-reducing medications. See 9.1, PRIMARY OPEN-ANGLE GLAUCOMA. The IOP may need to be reduced dramatically to eliminate corneal edema. This critical level may become lower as the patient ages.

- Hypertonic saline solutions (e.g., sodium chloride 5% drops q.i.d. and ointment q.h.s.) may reduce corneal edema.

- LT and laser PI are ineffective. Newer glaucoma surgical techniques and devices such as iStent are not indicated due to angle disorder. May consider filtering procedure (trabeculectomy) when medical therapy fails; however, there is higher rate of failure for glaucoma filtering surgery. Tube-shunt surgery preferred. If tube-shunt procedure is performed, place tube far into the anterior chamber to lessen the likelihood of occlusion with the endothelial membrane.

- Consider an endothelial transplant or full-thickness corneal transplant in cases of advanced chronic corneal edema in the presence of good IOP control.

Varies according to the IOP and optic nerve damage. If asymptomatic with healthy optic nerve, may see every 6 to 12 months. If glaucoma is present, then every 1 to 4 months, depending on the severity.