Painless floaters and decreased vision. Minimal photophobia or external inflammation. Most often bilateral and classically affects patients aged 15 to 40 years.

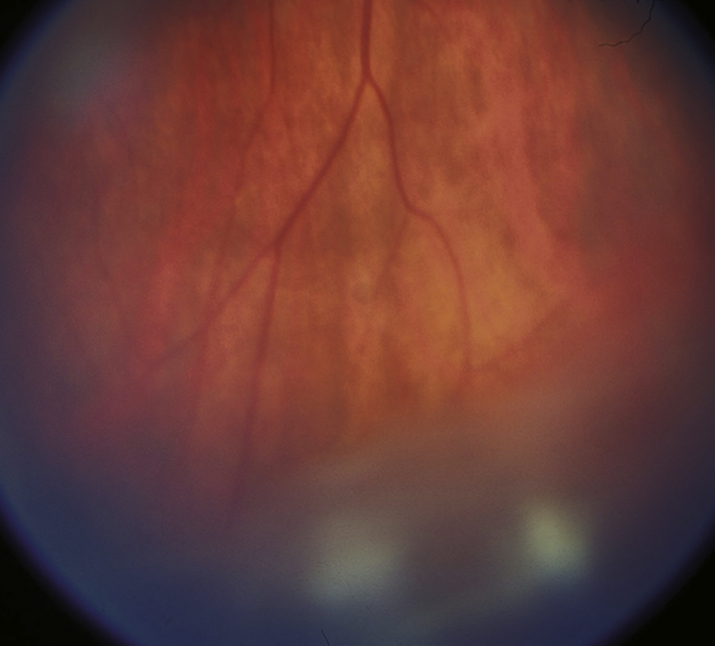

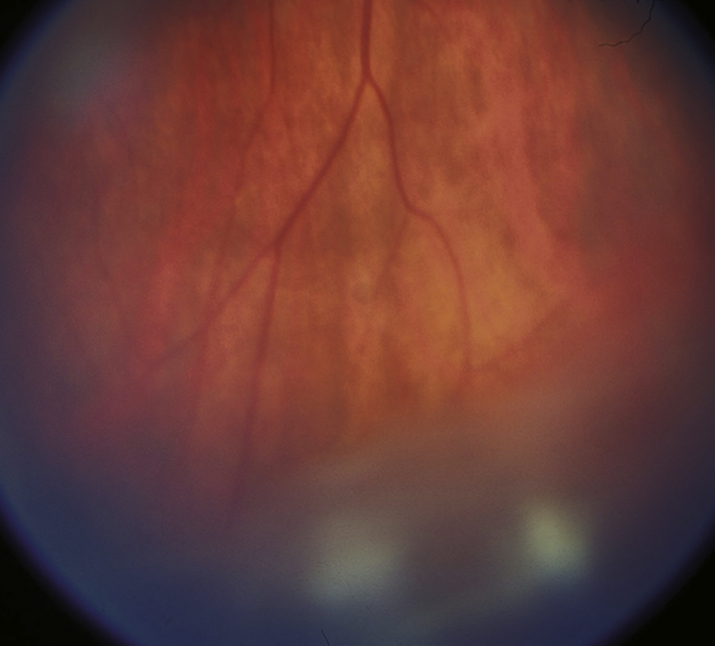

(See Figure 12.2.1.)

Critical

Vitreous cells and cellular aggregates floating predominantly in the inferior vitreous (snowballs). Younger patients may present with vitreous hemorrhage. White exudative material over the inferior ora serrata and pars plana (snowbank) is suggestive of pars planitis.

NOTE: NOTE: |

Snowbanking is typically in the inferior vitreous and can often be seen only with indirect ophthalmoscopy and scleral depression. |

Other

Peripheral retinal vascular sheathing, peripheral neovascularization, mild anterior chamber inflammation, CME, posterior subcapsular cataract, band keratopathy, secondary glaucoma, ERM, and exudative retinal detachment. Posterior synechiae in pars planitis are uncommon and, if present, usually occur early in the course of the disease. Choroidal neovascularization is rare.

12-2.1 Pars planitis/intermediate uveitis with snowballs.

Treat all vision-threatening complications (e.g., CME and vitritis) in symptomatic patients with active disease. Mild vitreous cell in the absence of symptoms, CME, or vision loss may be observed in cases of noninfectious intermediate uveitis.

- Topical prednisolone acetate 1% or difluprednate 0.05% q1–2h. Consider subtenon steroid (e.g., 0.5 to 1.0 mL injection of triamcinolone 40 mg/mL). May repeat the injections every 6 to 8 weeks until the vision and CME have stabilized. Slowly taper the frequency of injections. Subtenon steroid injections must be used with caution in patients with steroid-induced glaucoma. See Appendix 10, TECHNIQUE FOR RETROBULBAR/SUBTENON/SUBCONJUNCTIVAL INJECTIONS.

- If there is minimal improvement after three subtenon steroid injections 1 to 2 months apart, consider systemic steroids (e.g., prednisone 40 to 60 mg p.o. daily for 4 to 6 weeks), tapering gradually according to the patient’s response. High-dose systemic steroid therapy should last no longer than 2 to 3 months, followed by a taper to no more than 5 to 10 mg/d. Other options include sustained-release steroid implants (e.g., dexamethasone 0.7 mg intravitreal implant; fluocinolone acetonide 0.19 or 0.59 mg intravitreal implant) and immunomodulatory therapy (e.g., antimetabolites, calcineurin inhibitors, and anti-tumor necrosis factor agents), usually in conjunction with rheumatology.

- Transscleral cryotherapy to the area of snowbanking should be considered in patients who fail to respond to either oral or subtenon corticosteroids and who have neovascularization.

- Pars plana vitrectomy may be useful in cases refractory to systemic steroids or to treat vitreous opacification, tractional retinal detachment, ERM, and other complications. Additionally, vitreous biopsy through a pars plana vitrectomy may be indicated in cases of suspected masquerade syndromes, especially intraocular lymphoma.

NOTE: NOTE: |

- Some physicians delay steroid injections for several weeks to observe whether the IOP increases on topical steroids (steroid response). If a marked steroid response is found, depot injections should be avoided.

- Intravitreal preservative-free triamcinolone acetonide and the dexamethasone or fluocinolone acetonide implants are more effective for uveitic macular edema than periocular triamcinolone.

- Intravitreal anti-VEGF drugs (e.g., ranibizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept) are effective in the treatment of uveitic CME but only if the uveitis itself is suppressed.

- Oral acetazolamide 250 mg two to four times a day can reduce CME but is often not well tolerated due to nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, malaise, anorexia, or hypokalemia.

- Topical NSAIDs are usually not effective in patients with uveitic CME.

- Cataracts are a frequent complication of intermediate uveitis. If cataract extraction is performed, the patient should ideally be free of inflammation for 3 months preceding the operation. Consider starting the patient on oral prednisone 60 mg daily 2 to 5 days prior to surgery and tapering the prednisone over the next 1 to 4 weeks. Aggressive perioperative use of topical NSAIDS (e.g., ketorolac 0.5% q.i.d.) and topical steroids (e.g., prednisolone acetate 1% q2h or difluprednate 0.05% six times a day) starting 2 to 5 days preoperatively and continued for at least 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively may reduce the risk of pseudophakic CME and recurrent uveitis. Consider a combined pars plana vitrectomy at the time of cataract surgery if significant vitreous opacification is present.

|