Critical

- Cells and flare in the anterior chamber (see Tables 12.1.1 and 12.1.2) and ciliary flush.

Keratic Precipitates

- Fine KP: Herpes simplex or varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis (FHIC).

- Small, nongranulomatous KP (NGKP): HLA-B27-associated, trauma, masquerade syndromes, JIA, Posner–Schlossman syndrome (glaucomatocyclitic crisis), drug-induced. Granulomatous uveitides such as sarcoidosis can present with NGKP; the reverse rarely occurs.

- Granulomatous KP (large, greasy, “mutton-fat”; mostly on the inferior cornea): Sarcoidosis, syphilis, tuberculosis (TB), JIA-associated, sympathetic ophthalmia, lens-induced, Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) syndrome, and others.

- CMV uveitis often has characteristic “coin-shaped” KP not found in other herpetic uveitides.

- The location of KP can be helpful diagnostically.

- Diffuse KP are characteristic of FHIC and herpetic uveitides.

- KP underneath areas of stroma opacification suggest herpes simplex or, less often, varicella zoster keratouveitis.

- Granulomatous KP in an inferior peripheral crescent underneath areas of stromal haze (often with fine, deep stromal vascularization) are highly suggestive of sarcoidosis.

- Granulomatous KP in Arlt triangle (apex near central cornea, base at inferior limbus) are nonspecific.

- “Crenated” KP are translucent and discrete, usually medium-large lesions characteristic of regressed granulomatous anterior uveitis.

Other

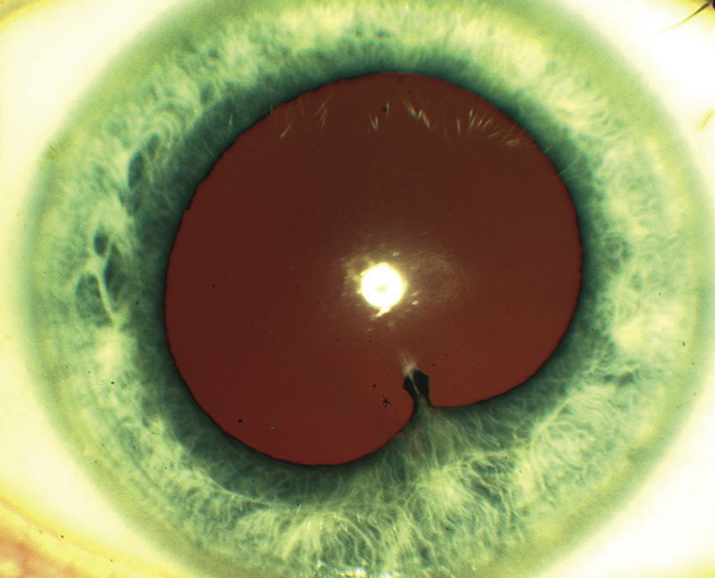

Low intraocular pressure (IOP) more commonly seen (secondary to ciliary body hyposecretion), elevated IOP can occur (e.g., herpetic, lens-induced, FHIC, Posner–Schlossman syndrome), fibrin (e.g., HLA-B27 or endophthalmitis), hypopyon (e.g., HLA-B27, Behçet disease, infectious endophthalmitis, rifabutin-induced, tumor), iris nodules (e.g., sarcoidosis, syphilis, TB), iris atrophy (e.g., herpetic, oral fourth-generation fluoroquinolones), iris heterochromia (e.g., FHIC), iris synechiae (especially HLA-B27, sarcoidosis), band keratopathy (especially JIA in younger patients, any chronic uveitis in older patients), uveitis in a “quiet eye” (consider JIA, FHIC, and masquerade syndromes), and CME (see Figure 12.1.1).