Red eye, moderate-to-severe ocular pain, photophobia, decreased vision, discharge, and acute contact lens intolerance.

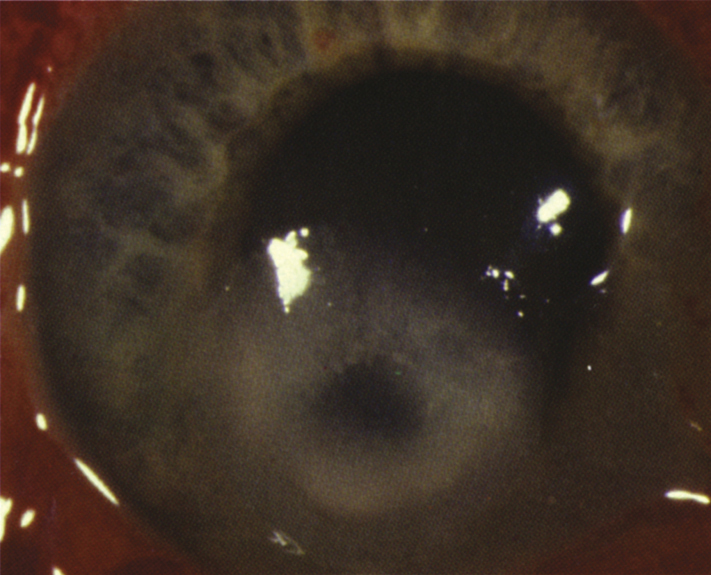

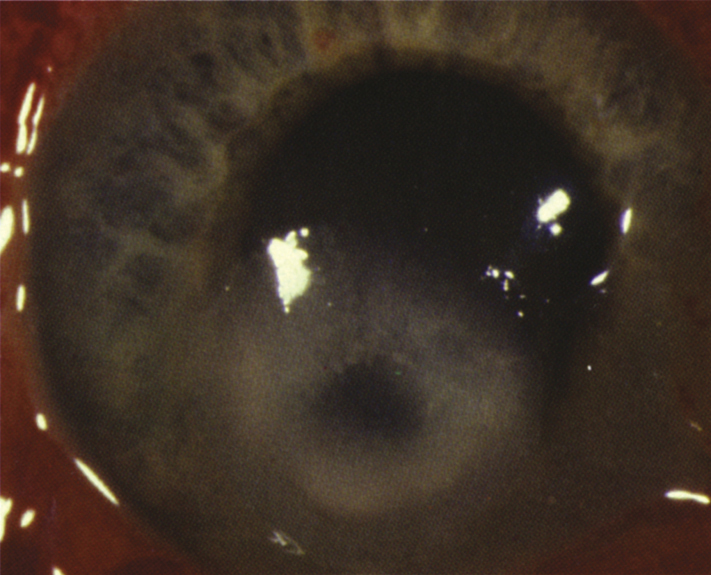

(See Figure 4.11.1.)

Critical

Focal white opacity (infiltrate) in the corneal stroma associated with an epithelial defect and underlying stromal thinning/tissue loss.

NOTE: NOTE: |

An examiner using a slit beam cannot see clearly through an infiltrate or ulcer to the iris, whereas stromal edema or mild anterior stromal scars are more transparent. |

Other

Epithelial defect, mucopurulent discharge, stromal edema, folds in Descemet membrane, anterior chamber reaction, endothelial fibrin/cell deposition with or without hypopyon formation (which, in the absence of globe perforation, usually represents sterile inflammation), conjunctival injection, upper eyelid edema. Posterior synechiae, hyphema, and increased IOP may occur in severe cases.

4-11.1 Bacterial keratitis.

Bacterial organisms are the most common cause of infectious keratitis. In general, corneal infections are assumed to be bacterial until proven otherwise by laboratory studies or until a therapeutic trial of topical antibiotics is unsuccessful. At Wills Eye, the most common causes of bacterial keratitis are Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Moraxella, and Serratia species. Clinical findings vary widely depending on the severity of disease and on the organism involved. The following clinical characteristics may be helpful in predicting the organism involved. However, clinical impression should never take the place of broad-spectrum initial treatment and appropriate laboratory evaluation. See Appendix 8, CORNEAL CULTURE PROCEDURE.

- Staphylococcal ulcers typically have a well-defined, gray-white stromal infiltrate that may enlarge to form a dense stromal abscess.

- Streptococcal infiltrates may be either very purulent or crystalline (see 4.14, CRYSTALLINE KERATOPATHY). Acute fulminant onset with severe anterior chamber reaction and hypopyon formation are common in the former, while the latter tends to have a more indolent course and occurs in patients often on chronic topical steroids (e.g., corneal transplant patients).

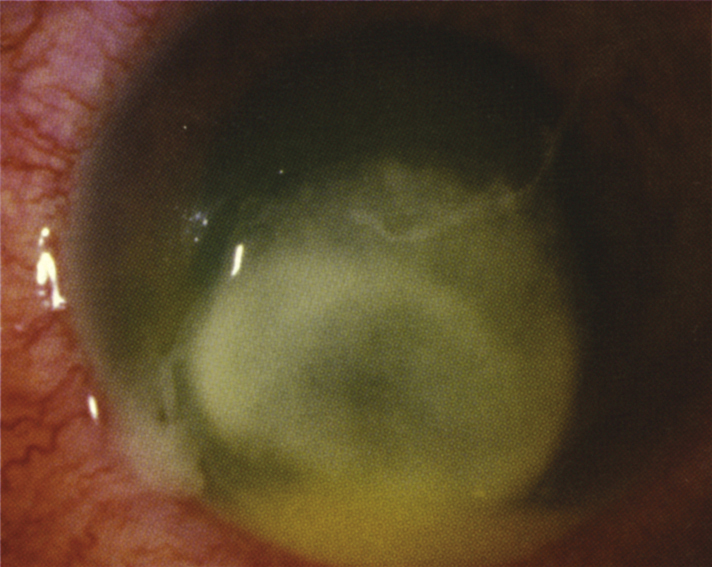

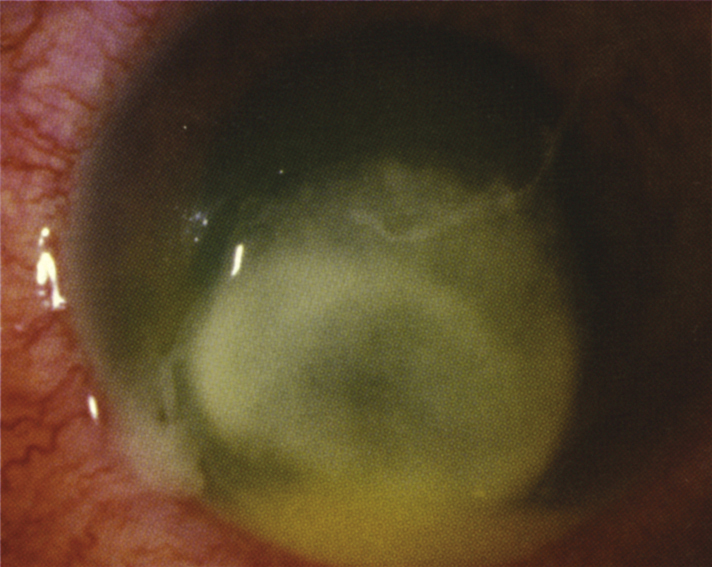

- Pseudomonas typically presents as a rapidly progressive, suppurative, necrotic infiltrate associated with a hypopyon and mucopurulent discharge, commonly seen in the setting of soft contact lens wear (see Figure 4.11.2).

- Moraxella may cause infectious keratitis in patients with preexisting ocular surface disease and in patients who are immunocompromised. Infiltrates are typically indolent, located in the inferior portion of the cornea, have a tendency to be full-thickness, and may rarely perforate.

4-11.2 Pseudomonas keratitis.

Ulcers and infiltrates are initially treated as bacterial unless there is a high index of suspicion of another form of infection. Initial therapy should be broad spectrum. Remember that bacterial coinfection may occasionally complicate fungal and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Mixed bacterial infections can also occur.

- Cycloplegic drop for comfort and to prevent synechiae formation (e.g., cyclopentolate 1% t.i.d.; atropine 1% b.i.d. to t.i.d. recommended if a hypopyon in present). The specific medication depends on severity of anterior chamber inflammation.

- Topical antibiotics according to the following algorithm:

Low Risk of Visual Loss

Small, nonstaining peripheral infiltrate with at most minimal anterior chamber reaction and no discharge:

- Noncontact lens wearer: Broad-spectrum topical antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolone [moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, besifloxacin, levofloxacin] or polymyxin B/trimethoprim drops q1–2h while awake).

- Contact lens wearer: Fluoroquinolone (e.g., moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, ciprofloxacin, besifloxacin, levofloxacin) drops q1–2h while awake ± polymyxin B/trimethoprim drops q1–2h while awake; can add tobramycin or ciprofloxacin ointment one to four times a day.

Borderline Risk of Visual Loss

Medium size (1 to 1.5 mm diameter) peripheral infiltrate, or any smaller infiltrate with an associated epithelial defect, mild anterior chamber reaction, or moderate discharge:

- Fluoroquinolone (e.g., moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, ciprofloxacin, besifloxacin, levofloxacin) q1h around the clock ± polymyxin B/trimethoprim q1h around the clock. Consider starting with a loading dose of q5min for five doses and then q30min until midnight then q1h.

NOTE: NOTE: |

Moxifloxacin and besifloxacin have slightly better gram-positive coverage. Gatifloxacin and ciprofloxacin have slightly better Pseudomonas and Serratia coverage. |

Vision Threatening

Our current practice at Wills Eye is to start fortified antibiotics for most ulcers larger than 1.5 to 2 mm, in the visual axis, or unresponsive to initial treatment. See Appendix 9, FORTIFIED TOPICAL ANTIBIOTICS/ANTIFUNGALS, for directions on making fortified antibiotics. If fortified antibiotics are not immediately available, start with a fluoroquinolone and polymyxin B/trimethoprim until fortified antibiotics can be obtained from a formulating pharmacy.

- Fortified tobramycin or gentamicin (15 mg/mL) q1h, alternating with fortified cefazolin (50 mg/mL) or vancomycin (25 mg/mL) q1h. This means that the patient will be placing a drop in the eye every one-half hour around the clock. Vancomycin drops should be reserved for resistant organisms, patients at risk for resistant organisms (e.g., due to hospital or antibiotic exposure, unresponsive to initial treatment), and for patients who are allergic to penicillin or cephalosporins. An increasing number of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections are now community acquired. If the ulcer is severe and Pseudomonas is suspected, consider starting fortified tobramycin every 30 minutes and fortified cefazolin q1h around the clock; in addition, consider fortified ceftazidime q1h or a fluoroquinolone q1h around the clock.

NOTE: NOTE: |

All patients with borderline risk of visual loss or severe vision-threatening ulcers are initially treated with loading doses of antibiotics using the following regimen: One drop every 5 minutes for five doses, then every 30 to 60 minutes around the clock. |

- In some cases, topical steroids are added after the bacterial organism and sensitivities are known, the infection is under control, and severe inflammation persists. Infectious keratitis may worsen significantly with topical steroids, especially when caused by fungus, atypical mycobacteria, Nocardia or Pseudomonas.

- Eyes with corneal thinning should be protected by a shield without a pressure patch (a patch is never placed over an eye thought to have an infection). The use of a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor (e.g., doxycycline 100 mg p.o. b.i.d.) and a collagen synthesis promoter such as systemic ascorbic acid (e.g., vitamin C 1 to 2 g daily) may help to suppress connective tissue breakdown and prevent the perforation of the cornea.

- No contact lens wear.

- Oral pain medication as needed.

- Oral fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin 500 mg p.o. b.i.d.; moxifloxacin 400 mg p.o. daily) penetrate the eye well. These may have added benefit for patients with scleral extension or for those with frank or impending perforation. Ciprofloxacin is preferred for Pseudomonas and Serratia.

- Systemic antibiotics are also necessary for Neisseria infections (e.g., ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously [i.v.] q12–24h if corneal involvement, or a single 1 g intramuscular [i.m.] dose if there is only conjunctival involvement) and for Haemophilus infections (e.g., oral amoxicillin/clavulanate [20 to 40 mg/kg/d in three divided doses]) because of occasional extraocular involvement such as otitis media, pneumonia, and meningitis.

- Admission to the hospital may be necessary if:

- Infection is sight threatening and/or impending perforation.

- Patient has difficulty administering the antibiotics at the prescribed frequency.

- High likelihood of noncompliance with drops or daily follow up.

- Suspected topical anesthetic abuse.

- Intravenous antibiotics are needed (e.g., gonococcal conjunctivitis with corneal involvement). Often employed in the presence of corneal perforation and/or scleral extension of infection.

- For atypical mycobacteria, consider prolonged treatment (q1h for 1 week, then gradually tapering) with one or more of the following topical agents: fluoroquinolone (e.g., moxifloxacin or gatifloxacin), fortified amikacin (15 mg/mL), clarithromycin (1% to 4%), or fortified tobramycin (15 mg/mL). Consider oral treatment with clarithromycin 500 mg b.i.d. Previous LASIK has been implicated as a risk factor for atypical mycobacteria infections.

NOTE: NOTE: |

Systemic fluoroquinolones were historically used for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, but are no longer recommended to treat gonococcal infections (especially in men who have sex with men, in areas of high endemic resistance, and in patients with a recent foreign travel history) due to increased resistance. Additionally, they are contraindicated in pregnant women and children. |