Pain, photophobia, red eye; may be asymptomatic.

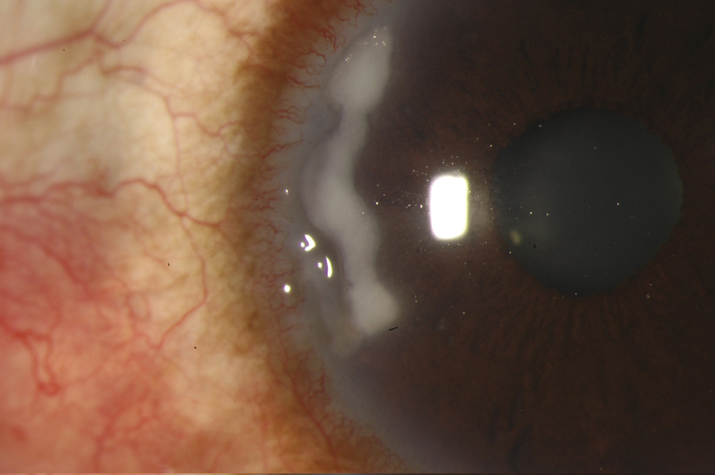

Peripheral corneal thinning (best seen with a narrow slit beam); may be associated with sterile infiltrate or ulcer.

Infectious infiltrate or ulcer. Lesions are often treated as infectious until cultures come back negative. See 4.11, BACTERIAL KERATITIS.

See sections on delle, staphylococcal hypersensitivity, dry eye syndrome, exposure and neurotrophic keratopathies, scleritis, vernal conjunctivitis, and ocular rosacea.

- 1.PUK associated systemic immune-mediated disease: Management is usually coordinated with an internist or rheumatologist.

- Ophthalmic antibiotic ointment (e.g., erythromycin ointment) or preservative-free artificial tear ointment q2h.

- Cycloplegic drop (e.g., cylopentolate 1% or atropine 1% b.i.d. to t.i.d.) when an anterior chamber reaction or pain is present.

- Consider doxycycline 100 mg p.o. b.i.d. for its metalloproteinase inhibition properties and ascorbic acid (vitamin C 1 to 2 g daily) as a collagen synthesis promoter.

- Systemic steroids (e.g., prednisone 60 to 100 mg p.o. daily; dosage is adjusted according to the response) and antiulcer prophylaxis (e.g., ranitidine 150 mg p.o. b.i.d. or pantoprazole 40 mg daily) are used for significant and progressive corneal thinning, but not for perforation.

- An immunosuppressive agent (e.g., methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, infliximab, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide) is often required, especially for GPA. This should be done in coordination with the patient’s internist or rheumatologist.

- Excision or recession of adjacent inflamed conjunctiva is occasionally helpful when the condition progresses despite treatment.

- Punctal occlusion if dry eye syndrome is present. Topical cyclosporine 0.05% to 2% b.i.d. to q.i.d. or lifitegrast 5% b.i.d. may also be helpful. See 4.3, DRY EYE SYNDROME.

- Consider cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive or corneal transplantation surgery for an impending or actual corneal perforation. A conjunctival flap or amniotic membrane graft can also be used for an impending corneal perforation.

- Patients with significant corneal thinning should wear their glasses (or protective glasses [e.g., polycarbonate lens]) during the day and an eye shield at night.

- Terrien marginal degeneration: Correct astigmatism with glasses or contact lenses if possible. Protective eyewear should be worn if significant thinning is present. Lamellar grafts can be performed if thinning is extreme.

- Mooren ulcer: Underlying systemic diseases must be ruled out before this diagnosis can be made. Topical steroids, topical cyclosporine 0.05% to 2%, limbal conjunctival excision, corneal gluing, and lamellar or penetrating keratoplasty may be beneficial. Systemic immunosuppression (e.g., oral steroids, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine) has been described.

- Pellucid marginal degeneration: See 4.24, KERATOCONUS.

- Furrow degeneration: No treatment is required.

NOTE: NOTE: |

Topical steroids should be used with caution in the presence of significant corneal thinning because of the risk of perforation. Gradually taper topical steroids if the patient is already taking them. Notably, corneal thinning due to relapsing polychondritis may improve with topical steroids (e.g., prednisolone acetate 1% q1–2h). |

Patients with severe disease are examined daily; those with milder conditions are checked less frequently. Watch carefully for signs of superinfection (e.g., increased pain, stromal infiltration, anterior chamber cells and flare, conjunctival injection), increased IOP, and progressive corneal thinning. Treatment is maintained until the epithelial defect over the ulcer heals and is then gradually tapered. As long as an epithelial defect is present, there is risk of progressive thinning and perforation.