Painless loss of vision, usually unilateral.

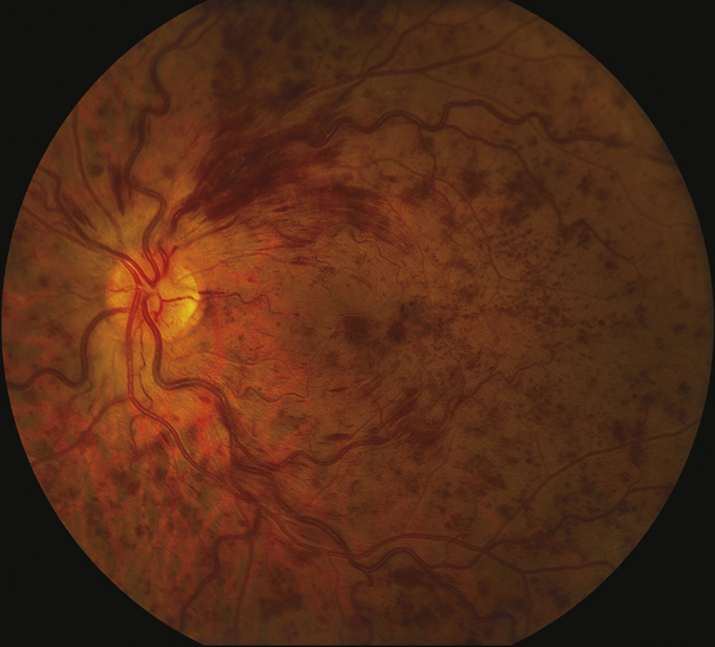

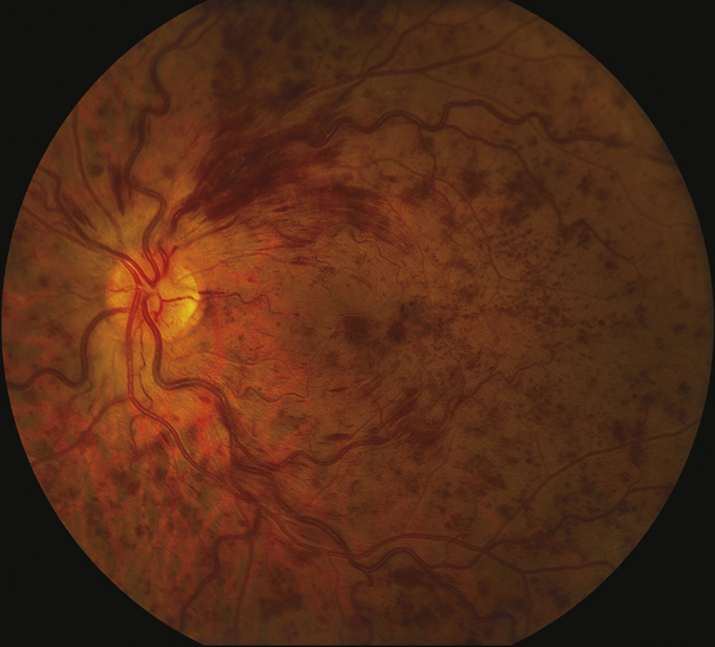

(See Figure 11.8.1.)

Critical

Diffuse retinal hemorrhages in all four quadrants of the retina; dilated, tortuous retinal veins.

Other

CWSs; disc edema and hemorrhages; macular edema (ME); optociliary collateral vessels on the disc (later finding); NVD, NVI, NVA, and NVE.

11-8.1 Central retinal vein occlusion with dilated, tortuous vasculature, diffuse retinal hemorrhages in all four quadrants, and macular edema.

Brown DM, Campochiaro PA, Singh RP, et al. Ranibizumab for macular edema following central retinal vein occlusion: six-month primary end point results of a phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1124-1133.Haller JA, Bandello F, Belfort R Jr, et al. Randomized sham-controlled trial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with macular edema due to retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1134-1146.Ip MS, Scott IU, VanVeldhuisen PC, et al. A randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of intravitreal triamcinolone with observation to treat vision loss associated with macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion: the Standard Care vs Corticosteroid for Retinal Vein Occlusion (SCORE) study report 5. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(9):1101-1114.Boyer D, Heier J, Brown DM, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor Trap-Eye for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion: six-month results of the Phase III COPERNICUS Study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1024-1032.