- Primarily intraconal/optic nerve:

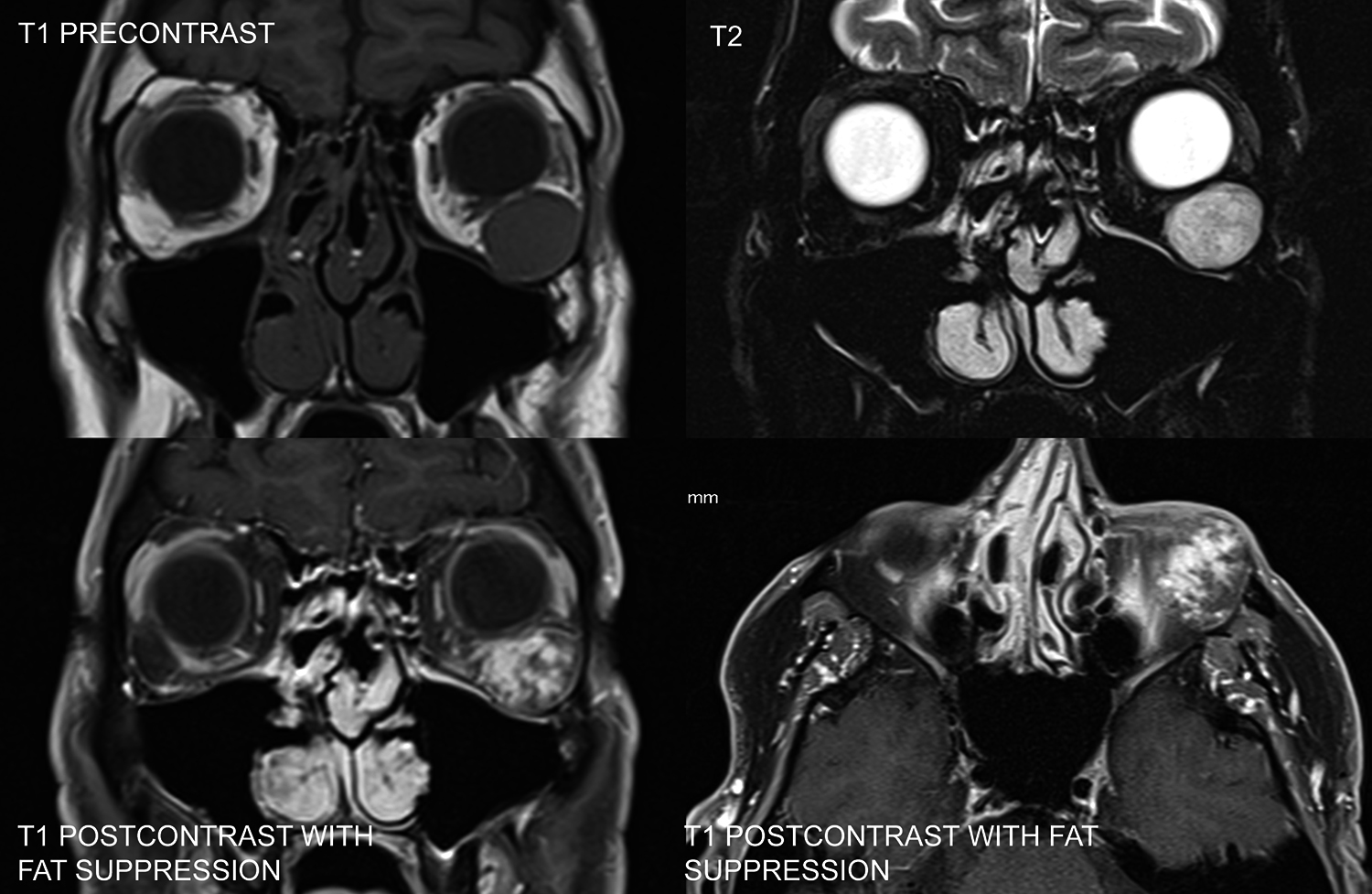

- Cavernous venous malformation (cavernous hemangioma): Most common benign orbital mass in adults. Middle-aged women most commonly affected, with a slow onset of orbital signs. Growth may accelerate during pregnancy (see Figure 7.4.2.1).

- Mesenchymal tumors: Orbital lesions with varying degrees of aggressive behavior. The largest group is now labeled solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) and includes fibrous histiocytoma and hemangiopericytoma. These lesions cannot be distinguished clinically or radiographically. May occur at any age. Immunohistochemical staining for STAT6 is usually diagnostic.

- Neurilemmoma (schwannoma): Progressive, painless proptosis. Rarely associated with neurofibromatosis type II. Malignant schwannoma has been reported but is rare.

- Neurofibroma: See 7.4.1, ORBITAL TUMORS IN CHILDREN.

- Meningioma: Optic nerve sheath meningioma (ONSM) typically occurs in middle-aged women with painless, slowly progressive visual loss, often with mild proptosis. An afferent pupillary defect may be present. Ophthalmoscopy can reveal optic nerve swelling, optic atrophy, or abnormal collateral vessels around the optic nerve head (optociliary shunts).

- Other optic nerve lesions: Optic nerve glioma, optic nerve sarcoid, malignant optic nerve glioma of adulthood (MOGA). The second most common lesion of the optic nerve (excluding optic neuritis) after ONSM is optic nerve sarcoid, which may be difficult to distinguish from ONSM clinically and radiologically. The ACE level may be normal in cases of isolated optic nerve sarcoid. MOGA is a rapidly progressive optic nerve lesion of the elderly akin to glioblastoma multiforme; it carries a poor prognosis and is often misdiagnosed as a “progressive NAION.”

- Lymphangioma: Usually discovered in childhood. See 7.4.1, ORBITAL TUMORS IN CHILDREN.

- Primarily extraconal:

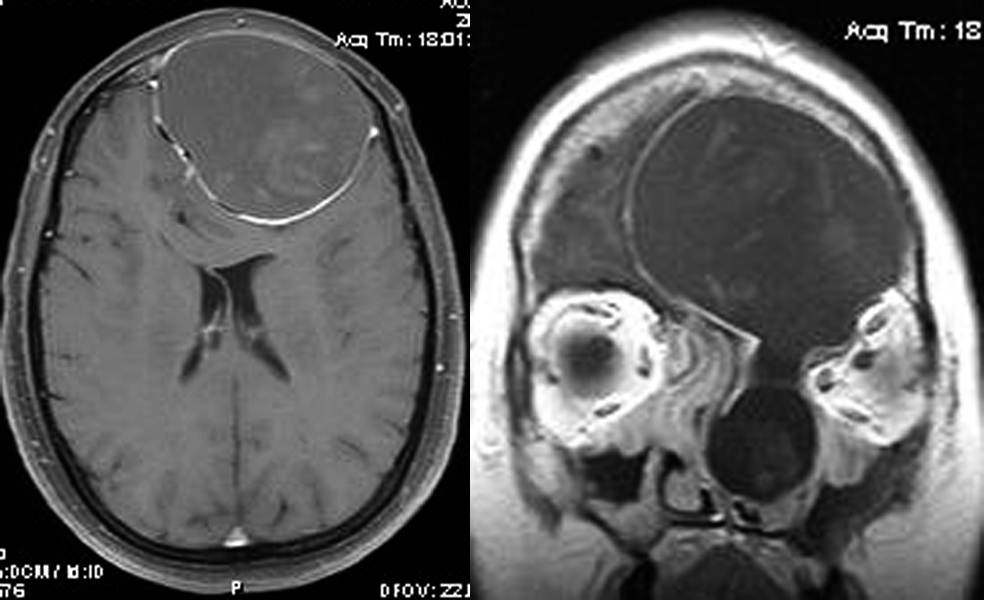

- Mucocele: Often presents with a frontal headache and a history of chronic sinusitis or sinus trauma. Usually located nasally or superonasally, emanating from the frontal and ethmoid sinuses. See Figure 7.4.2.2.

- Localized neurofibroma: Occurs in young- to middle-aged adults with the slow development of orbital signs. Eyelid infiltration results in an S-shaped upper eyelid. Some have neurofibromatosis type I, but most do not.

- SPA or spontaneous hematoma: See 7.3.2, SUBPERIOSTEAL ABSCESS.

- Dermoid cyst: See 7.4.1, ORBITAL TUMORS IN CHILDREN.

- Others: Tumors of the lacrimal gland (pleomorphic adenoma [well circumscribed], adenoid cystic carcinoma [ACC] [variably circumscribed with adjacent bone destruction]), sphenoid wing meningioma (commonly occurring in middle-aged females and a cause of compressive optic neuropathy), secondary tumors extending from the brain or paranasal sinuses, primary osseous tumors, and vascular lesions (e.g., varix and arteriovenous malformation including CCF).

- Intraconal or extraconal:

- Lymphoproliferative disease (lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoma): More commonly extraconal. About 50% are well circumscribed on imaging, and 50% are infiltrative. Ocular adnexal lymphoma is typically of the non-Hodgkin B-cell type (NHL), and about 75% to 85% follow an indolent course (extranodal marginal zone lymphoma [EMZL] or mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, grade I or II follicular cell lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [small cell lymphoma]). The remainder are aggressive lesions (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma, among others). May occur at any adult age; orbital NHL is rare in children. Slow onset and progression unless there is an aggressive subtype. Pain may occur in up to 25% of orbital NHL. Typically develops superiorly in the anterior aspect of the orbit, with about 50% occurring in the lacrimal gland. May be accompanied by a subconjunctival salmon-colored lesion. Most orbital NHL (especially if indolent subtype) occurs without evidence of systemic lymphoma (Stage IE). Orbital NHL may be confused with IOIS, especially when it presents more acutely with pain. Note that NHL frequently responds dramatically to systemic corticosteroids, as does IOIS.

- Metastases: Usually occurs in middle-aged to elderly people with a variable onset of orbital signs. Common primary sources include the breast (most common in women), lung (most common in men), and genitourinary tract (especially prostate). Twenty percent of orbital breast cancer metastases are bilateral and frequently involve extraocular muscles. Enophthalmos (not proptosis) may be seen with scirrhous breast carcinoma. Metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma has a propensity for bone and often involves the zygoma or greater sphenoid wing. Note that uveal metastases are far more common than orbital lesions by a 10 to 1 ratio.

- Others: Mesenchymal tumors and other malignancies.