Typically bilateral, progressive corneal disorders without inflammation or corneal neovascularization. No relationship to environmental or systemic factors. Most are autosomal dominant disorders except for macular dystrophy, type 3 lattice dystrophy, and congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy which are autosomal recessive.

EPITHELIAL AND SUBEPITHELIAL DYSTROPHIES

Epithelial Basement Membrane Dystrophy (Map–Dot–Fingerprint Dystrophy)

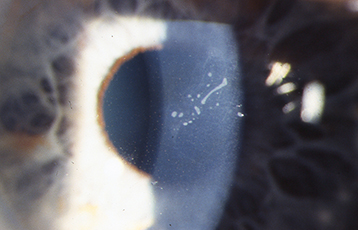

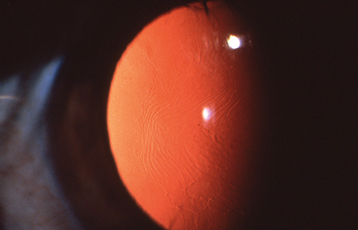

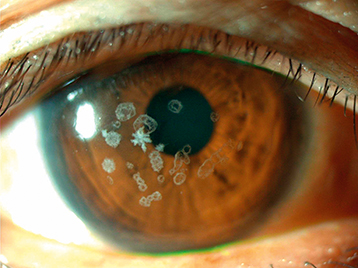

Most common anterior dystrophy. Diffuse gray patches (maps), creamy-white cysts (dots), or fine refractile lines (fingerprints) in the corneal epithelium, best seen with retroillumination or a broad slit-lamp beam angled from the side (see Figures 4.26.1 and 4.26.2). Spontaneous painful corneal erosions may develop, particularly on opening the eyes after sleep. May cause decreased vision, monocular diplopia, and shadow images. See 4.2, Recurrent Corneal Erosion, for treatment.

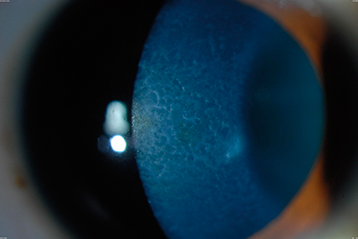

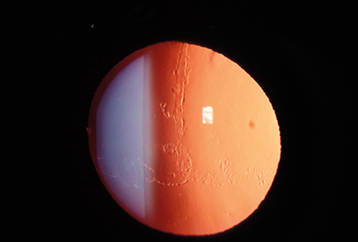

Rare, epithelial dystrophy that is seen in the first years of life, but is usually asymptomatic until middle age. Retroillumination shows discrete, tiny epithelial vesicles involving the whole cornea but can be segmental (see Figure 4.26.3). Although treatment is usually not required, bandage soft contact lenses or superficial keratectomy may be beneficial if significant photophobia is present or if visual acuity is severely affected.

Figure 4.26.3: Meesmann corneal dystrophy demonstrating multiple tiny discrete vesicles in direct illumination.

Epithelial–Stromal TGFBI Dystrophies: Reis–Bücklers and Thiel–Behnke

Appears early in life. Subepithelial, gray reticular opacities are seen primarily in the central cornea (see Figure 4.26.4). Painful episodes from recurrent erosions are relatively common and require treatment. Corneal transplantation surgery may be necessary to improve vision, but the dystrophy often recurs in the graft. Excimer laser PTK or superficial lamellar keratectomy may be adequate treatment in many cases.

CORNEAL STROMAL DYSTROPHIES

When these conditions cause reduced vision, patients usually benefit from a corneal transplant (lamellar or penetrating) or excimer laser PTK.

Type 1 (most common): Refractile branching lines, white subepithelial dots, and scarring of the corneal stroma centrally, best seen with retroillumination. Recurrent erosions are common (see 4.2, Recurrent Corneal Erosion). The corneal periphery is typically clear (see Figure 4.26.5). Tends to recur within 5 years after excimer laser PTK or corneal transplantation.

Type 2 (Meretoja syndrome): Associated with systemic amyloidosis, mask-like facies, ear abnormalities, cranial and peripheral nerve palsies, and dry and lax skin.

Types 3 and 4: Symptoms delayed until fifth to seventh decades.

Classic granular dystrophy. White anterior stromal deposits in the central cornea, separated by discrete clear intervening spaces (“bread-crumb-like” opacities) (see Figure 4.26.6). The corneal periphery is spared. Appears in the first decade of life but rarely becomes symptomatic before adulthood. Recurrent erosions can occur. Also may recur after excimer laser PTK or corneal transplantation within 5 years.

Also known as combined granular-lattice dystrophy or Avellino dystrophy. Similar to granular dystrophy type I but with significant amyloid deposition consistent with lattice dystrophy.

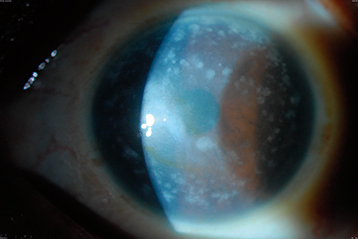

Gray-white stromal opacities with ill-defined edges extending from limbus to limbus with cloudy intervening spaces (see Figure 4.26.7). Can involve the full thickness of the stroma, more superficial centrally and deeper peripherally. Corneas tend to be flatter and thinner than normal. Causes late decreased vision more commonly than recurrent erosions. May recur many years after corneal transplantation. Autosomal recessive.

Fine, yellow-white anterior stromal crystals located in the central cornea are seen in half of the patients (see Figure 4.26.8). Corneas later develop full-thickness central haze and a dense arcus senilis. Workup includes fasting serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels due to association with systemic lipid abnormalities. Can compromise vision enough to require excimer laser PTK or corneal transplantation. See 4.15, Crystalline Keratopathy.

DESCEMET MEMBRANE AND ENDOTHELIAL DYSTROPHIES

See 4.27, Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy.

Posterior Polymorphous Corneal Dystrophy

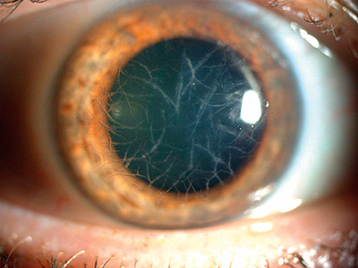

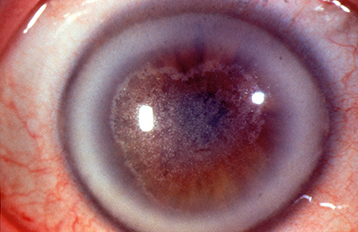

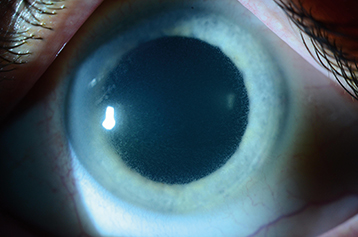

Changes at the level of Descemet membrane, including vesicles arranged in a linear or grouped pattern, diffuse blotchy gray haze, or broad bands with irregular, scalloped edges (see Figure 4.26.9). Iris abnormalities, including iridocorneal adhesions and corectopia (a decentered pupil), may be present and are occasionally associated with corneal edema. Glaucoma may occur. See 8.14, Developmental Anterior Segment and Lens Anomalies/Dysgenesis, for differential diagnosis. Treatment includes management of corneal edema and corneal transplantation for severe cases.

Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy

Bilateral corneal edema (often asymmetric), normal corneal diameter, normal IOP, and no cornea guttae. Present at birth, nonprogressive, associated with nystagmus. Pain or photophobia uncommon. Rare. Autosomal recessive. (See 8.14, Congenital/Infantile Glaucoma, for differential diagnosis.)

Some patients may benefit from a corneal transplant (endothelial or penetrating keratoplasty).