- Chapter 9 Systems Development Life Cycle: Nursing Informatics and Organizational Decision-Making

- Chapter 10 Administrative Information Systems

- Chapter 11 The Human-Technology Interface

- Chapter 12 Electronic Security

- Chapter 13 Achieving Excellence by Managing Workflow and Initiating Quality Projects

Nursing informatics (NI) and information technology (IT) have invaded nursing, and some nurses are happy with the capabilities afforded by this specialty. Others, however, remain convinced that the changes wrought by IT are nothing more than a nuisance. In the past, nursing administrators have found the implementation of technology tools to be an expensive venture with minimal rewards. This disappointment is likely related to their lack of knowledge about NI, which caused nursing administrators to listen to vendors or other colleagues; in essence, it was decision-making based on limited and biased information. There were at least two reasons for the experience of limited rewards. First, nurses were rarely included in the testing and implementation of products designed for nurses and nursing tasks and workflows. Second, the new products they purchased had to interface with old, legacy systems that were not at all compatible or that seemed compatible until the glitches arose. These glitches caused frustration for clinicians and administrators alike. They purchased tools that should have made the nurses happy, but instead all they did was grumble.

The good news is that approaches have changed as a result of the difficult lessons learned from the early forays into technology tools. Nursing personnel are involved at both the agency and the vendor levels in the decision-making process and development of new systems and products charged with enhancing the practice of nursing. Older legacy systems are being replaced with newer systems that have more capacity to interface with other systems. Nurses and administrators have become more astute in the realm of NI, but there is still a long way to go. Chapter 9, Systems Development Life Cycle: Nursing Informatics and Organizational Decision-Making, introduces the systems development life cycle, which is used to make important and appropriate organizational decisions for technology adoption.

Administrators need information systems that facilitate their administrative role, and they particularly need systems that provide financial, risk management, quality assurance, human resources, payroll, patient registration, acuity, communication, and scheduling functions. The administrator must be open to learning about all the tools available. One of the most important tasks that an administrator can oversee and engage in is data mining, or the extraction of data and information from big data, which are sizable data sets that have been collected and warehoused. Data mining helps to identify patterns in aggregate data; gain insights; and, ultimately, discover and generate knowledge applicable to nursing science. To take advantage of these benefits, nursing administrators must become astute informaticists-knowledge workers who harness the information and knowledge at their fingertips to facilitate the practice of their clinicians, improve patient care, and advance the science of nursing.

Clinical information systems (CISs) have traditionally been designed for use by one unit or department within an institution. However, because clinicians working in other areas of the organization need access to this information, these data and information are generally used by more than one area. New initiatives continue to arise with the integration and enhancement of the electronic health record, which places institutions in the position of striving to manage their CISs through the electronic health record. Currently, there are many CISs, including nursing, laboratory, pharmacy, monitoring, and order entry plus additional ancillary systems, to meet the individual institution's needs. Chapter 10, Administrative Information Systems, provides an overview of administrative information systems and helps the reader to understand the powerful data aggregation and data mining tools afforded by these systems.

Chapter 11, The Human-Technology Interface, discusses the need to significantly improve quality and safety outcomes in the United States. Through the use of IT, the designs for human-technology interfaces can be radically improved so that the technology better fits both human and task requirements. A number of useful tools are currently available for the analysis, design, and evaluation phases of development life cycles and should be used routinely by informatics professionals to ensure that technology better fits both task and user requirements. In this chapter, the authors stress that the focus on interface improvement using these tools has dramatically improved patient safety in a specific area of health care: anesthesiology. With increased attention from informatics professionals and engineers, the same kinds of improvements are being made in other areas. The human-technology interface is a crucial area if the theories, architectures, and tools provided by the building block sciences are to be implemented.

Each organization must determine who can access and use its information systems and provide robust tools for securing information in a networked environment. Chapter 12, Electronic Security, addresses the important safeguards for protecting information. As new technologies designed to improve interprofessional collaboration and enhance patient care are adopted, barriers to implementation and resistance by practitioners to change are frequently encountered. Chapter 13, Achieving Excellence by Managing Workflow and Initiating Quality Projects, provides insights into clinical workflow analysis and advice on improving efficiency and effectiveness while reviewing what we have learned as we tried to achieve meaningful use of caring technologies. The Patient Room ‘Next' (PRN) initiative is reviewed. Any new technology implementation will affect work processes and disrupt workflow. Attention must be paid to this effect, and strategies must be implemented to minimize negative effects. Quality improvement projects are focused on improving work processes and patient safety after technologies have been implemented. Quality improvement projects employ many of the same strategies and metrics used in workflow analyses.

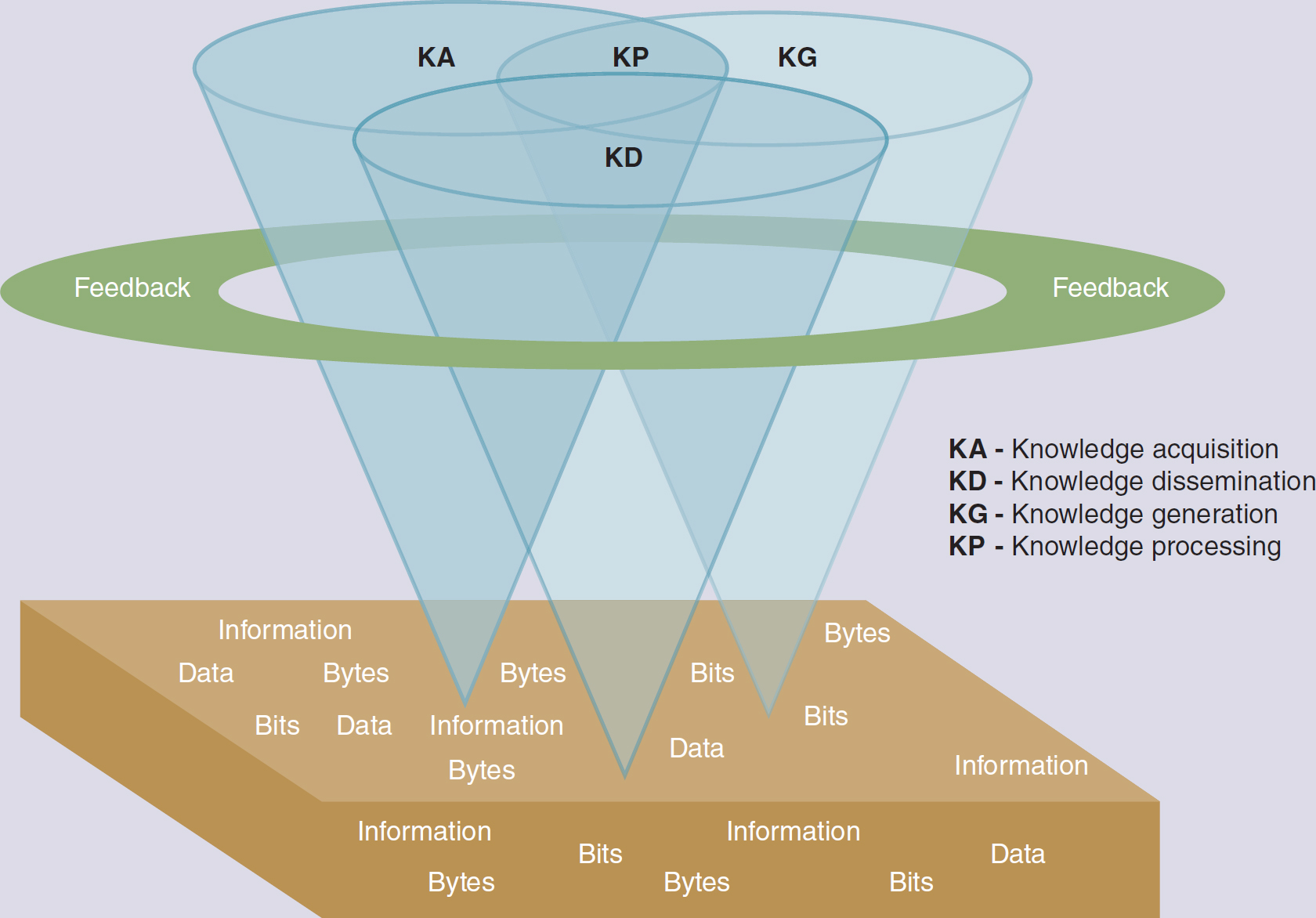

Pause to reflect on the Foundation of Knowledge model (Figure III-1) and its relationship to both personal and organizational knowledge management. Consider that organizational decision-making must be driven by appropriate information and knowledge developed in the organization and applied with wisdom. Equally important to adopting technology within an organization is the consideration of the knowledge base and knowledge capabilities of the individuals within that organization. Administrators must use the system development life cycle wisely and must carefully consider organizational workflow as they adopt NI technology for meaningful use.

Figure III-1 Foundation of Knowledge Model

An illustration depicts the structure of the Foundation of Knowledge model.

The model features a three-dimensional illustration of three entwined, inverted cones labeled K A, K G, and K D. The three labeled cones converge to create a new cone labeled K P. Encircling these cones is a feedback loop. The entire composition is situated on a platform featuring repeated words such as information, data, bytes, and bits. K A indicates knowledge acquisition; K D indicates knowledge dissemination; K G indicates knowledge generation; and K P denotes knowledge processing.

The reader of this section is challenged to ask the following questions: (1) How can I apply the knowledge gained from my practice setting to benefit my patients and enhance my practice? (2) How can I help my colleagues and patients understand and use the current technology that is available? and (3) How can I use my wisdom to create the theories, tools, and knowledge of the future?