AUTHORS: Sahar Mahani, MD and Craig L. Basman, MD, FACC, FSCAI

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a clinical syndrome that suggests limitation of coronary blood flow to the myocardium as a result of atherosclerotic lesions. Atherosclerosis can be defined as the narrowing of the artery due to plaque formation in the setting of lipid accumulation inside the arterial walls. It is silent in the early stages and characterized by exertional symptoms in later stages as described in the following text.

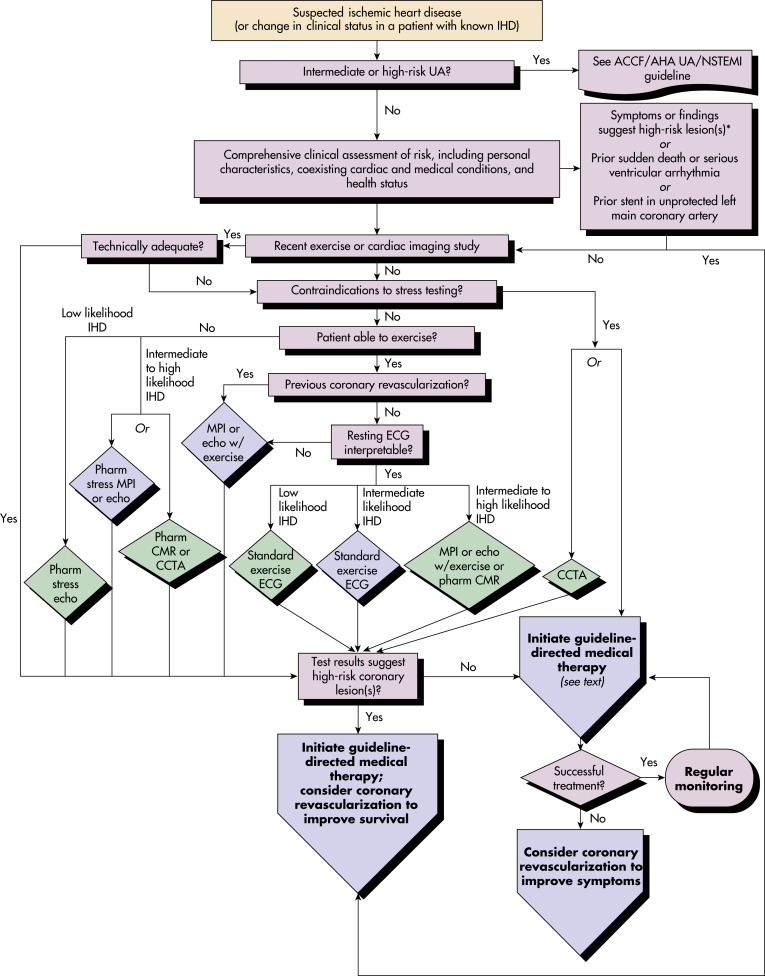

This topic addresses only stable CAD. Acute coronary syndromes (ACSs), angina pectoris, and myocardial infarction (MI) are addressed as separate topics elsewhere.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- For persons who are 40 yr old, the lifetime risk of developing CAD is 49% in men and 32% in women. The risk increases with age in both men and women; however, the incidence in women lags behind that seen in men by approximately 10 yr.

- The incidence in premenopausal women is relatively low, whereas the incidence increases significantly in postmenopausal women.

- The initial presentation in men is more likely to be that of an MI, whereas women often present initially with angina.

The 2017 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics update from the American Heart Association estimated that 16.5 million Americans ≥20 yr of age have CAD. There is a slight male predominance at 55%, with incidence increasing with age. CAD prevalence is 7.9% for men and 5.1% for women.1

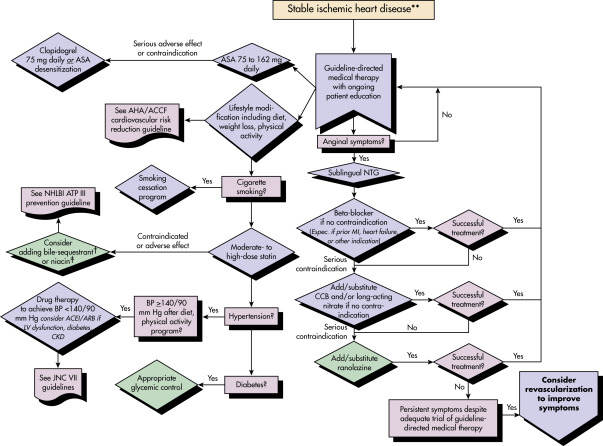

The most prevalent risk factors include tobacco use, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, family history, age, male sex, and peripheral vascular disease. Coronary plaque, especially noncalcified plaque, is more prevalent and extensive in HIV-infected men, independent of CAD risk factors.2,3

- Left anterior chest discomfort is often described as squeezing, heavy pressure, and burning. Associated symptoms include fatigue, dyspnea, weakness, lightheadedness, nausea, diaphoresis, altered mental status, and syncope.

- Discomfort that radiates to the neck, jaw, shoulder, and arm (left more than right) is common.

- Typical angina is exertional, resolves with rest after 3 to 5 min, and rarely lasts more than 30 min.

- Women and diabetes may not present with classic symptoms but may manifest more frequently with dyspnea or GI complaints.

- Discomfort is elicited by physical exertion, emotional stress, cold exposure, consumption of a large meal, and smoking.

- Early coronary disease is asymptomatic.

- Stigmata of atherosclerosis may include xanthelasma, tendon xanthomata, and evidence of peripheral vascular disease such as claudication and diminished peripheral pulses.

The process of atherosclerosis begins when the endothelium is damaged or dysfunctional by a variety of different pathways/disease states: Hypertension, hyperlipidemia, trauma, toxins from drugs or tobacco use, or endothelial dysfunction sometime thought to be related to genetics. When the endothelium is dysfunctional, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol circulating in the blood begins to accumulate within the intima. As the cholesterol accumulates within this plaque precursor, it begins to oxidize over time, which subsequently signals monocytes to migrate into the intima and convert to macrophages-this accumulation is known as a fatty streak. The macrophage cells enlarge and engulf cholesterol but can become overwhelmed and subsequently undergo apoptosis, leaving behind foam cells (the remnants of cholesterol-filled macrophages), as well as releasing inflammatory cytokines. Atherogenesis is further propagated by this resultant cellular necrosis within the forming plaque, promoting inflammatory mediator expression, intimal thickening, and migration of more macrophage cells.

Initially atheromatous plaques develop in an outward direction-positive remodeling, with enlargement of the external radius of the artery, thereby maintaining the inner luminal diameter and thus blood flow. Luminal obstruction and vascular calcification are both later stages of atherogenesis. As the process continues, a well-defined core of extracellular lipids form-the collection is, at this stage, called an atheroma or fibrous plaque. Signals from the apoptotic macrophages prompt smooth muscle cell migration from the media, accelerating plaque formation by multiple actions, including secretion of collagen and elastin forming a protein fibrous cap, deposition of calcium, and releasing signals for neovascularization. By this time in the formation of the atheroma, the internal elastin membrane has become dysfunctional, allowing the passage of smooth muscle cells and perforations of neovascularization. Due to the previously mentioned changes and thickening of the intimal layer, there can be luminal narrowing, which reduces flow and ultimately can lead to symptoms of ischemia. This process of atherosclerosis typically occurs over many years.4