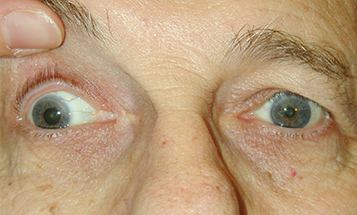

(See Figures 10.5.1 and 10.5.2. See Video: Third Cranial Nerve Palsy.)

Figure 10.5.2: Isolated right third cranial nerve palsy: Primary gaze showing right exotropia and dilated pupil.

An exotropia or hypotropia. Aberrant regeneration. See 10.6, Aberrant Regeneration of the Third Cranial Nerve.

Myasthenia gravis: Diurnal variation of symptoms and signs, pupil never involved, increased eyelid droop after sustained upgaze.

Thyroid eye disease: Eyelid lag, eyelid retraction, injection over the rectus muscles, proptosis, positive forced duction testing. See 7.2.1, Thyroid Eye Disease.

Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO): Bilateral, slowly progressive ptosis and motility limitation. Pupil spared, often no diplopia. See 10.12, Chronic Progressive External Ophthalmoplegia.

Idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome: Pain and proptosis common. See 7.2.2, Idiopathic Orbital Inflammatory Syndrome.

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO): Unilateral or bilateral adduction deficit with horizontal nystagmus of opposite abducting eye. No ptosis. See 10.13, Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia.

Skew deviation: Supranuclear brainstem lesion producing asymmetric, mainly vertical ocular deviation not consistent with single cranial nerve defect. See Differential Diagnosis in 10.7, Isolated Fourth Cranial Nerve Palsy.

Parinaud syndrome/dorsal midbrain lesion: Bilateral mid-dilated pupils that react poorly to light but constrict normally with convergence (not tonic). Associated with eyelid retraction (Collier sign), supranuclear upgaze paralysis, and convergence retraction nystagmus. No ptosis.

GCA: Extraocular muscle ischemia due to involvement of the long posterior ciliary arteries. Any extraocular muscle may be affected, resulting in potentially complex horizontal and vertical motility deficits. Pupil typically not involved. Age ≥55 years. See 10.17, Arteritic Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (Giant Cell Arteritis).

More common: Aneurysm, particularly posterior communicating artery aneurysm.

Less common: Tumor, trauma, congenital, uncal herniation, cavernous sinus mass lesion, pituitary apoplexy, orbital disease, varicella zoster virus, ischemia (e.g., diabetic), GCA, and leukemia. In children, ophthalmoplegic migraine.

Pupil-sparing: Ischemic microvascular disease; rarely cavernous sinus syndrome or GCA.

Relative pupil-sparing: Ischemic microvascular disease; less likely compressive.

Aberrant regeneration present: Trauma, aneurysm, tumor, congenital. Not microvascular. See 10.6, Aberrant Regeneration of the Third Cranial Nerve.

History: Onset and duration of diplopia? Recent trauma? Pertinent medical history (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, known cancer or central nervous system [CNS] mass, recent infections). If ≥55 years old, ask specifically about GCA symptoms.

Complete ocular examination: Check for pupillary involvement, the directions of motility restriction (in both eyes), ptosis, a visual field defect (visual fields by confrontation), proptosis, resistance to retropulsion, orbicularis muscle weakness, and eyelid fatigue with sustained upgaze. Look carefully for signs of aberrant regeneration. See 10.6, Aberrant Regeneration of the Third Cranial Nerve.

Neurologic examination: Carefully assess the other cranial nerves on both sides.

Immediate CNS imaging to rule out mass/aneurysm is indicated for all third cranial nerve palsies whether pupil-involving or pupil-sparing. One possible exception is a patient with complete sparing of the pupil and complete involvement of the other muscles (i.e., complete ptosis and complete paresis of extraocular muscles innervated by the third cranial nerve).

Cerebral angiography is indicated for all patients >10 years of age with pupil-involving third cranial nerve palsies and whose imaging study is not definitively negative or reveals findings suggestive of an aneurysm.

Ice test, rest test, or edrophonium chloride test when myasthenia gravis is suspected.

For suspected ischemic disease: Check blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, and hemoglobin A1c.

Immediate erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and platelet count if GCA is suspected. See 10.17, Arteritic Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (Giant Cell Arteritis).

If the third cranial nerve palsy is causing symptomatic diplopia, an occlusion patch or prism may be placed over the involved eye. Patching is usually not performed in children <11 years of age because of the risk of amblyopia. Children should be monitored closely for the development of amblyopia in the deviated eye.

Strabismus surgery may be considered for persistent significant misalignment.

Follow-up intervals vary depending on underlying disorder and stability of examination findings. Comanagement with medicine, neurosurgery, and/or neurology may be necessary.

If secondary to ischemia, function should return within 3 months. Refer to internist for management of vasculopathic disease risk factors.

If pupil-involving and imaging/angiography are negative, an LP should be considered.