THYROID EYE DISEASE

SYNONYMS: THYROID-RELATED ORBITOPATHY, GRAVES DISEASE

Early: Nonspecific complaints including foreign-body sensation, redness, tearing, photophobia, and morning puffiness of the eyelids. Early symptoms are often nonspecific and may mimic allergy, blepharoconjunctivitis, chronic conjunctivitis, etc. Upper eyelid retraction tends to develop early.

Late: Additional eyelid and orbital symptoms including lateral flare, prominent eyes, persistent eyelid swelling, chemosis, double vision, “pressure” behind the eyes, and decreased vision.

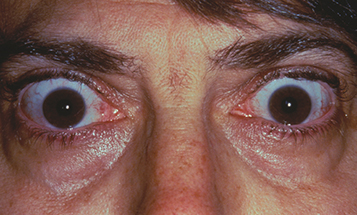

(See Figure 7.2.1.1.)

Retraction of the upper eyelids with lateral flare (highly specific) and eyelid lag on downward gaze (von Graefe sign), lagophthalmos. Lower eyelid retraction is a very nonspecific sign and often presents as a normal finding. Unilateral or bilateral axial proptosis with variable resistance to retropulsion. When extraocular muscles (EOMs) are involved, elevation and abduction are commonly restricted and there is resistance on forced duction testing. Although often bilateral, unilateral or asymmetric TED is also frequently seen. Thickening of the EOMs (inferior, medial, superior, and lateral, in order of frequency) without the involvement of the associated tendons may be noted on orbital imaging. Isolated enlargement of lateral rectus muscles is highly atypical of TED and requires further workup and possibly a biopsy. Isolated enlargement of the superior rectus/levator complex can occur in TED, but should be followed carefully for alternative causes, especially when upper eyelid retraction is not present.

Reduced blink rate, significantly elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) (especially in upgaze), injection of the blood vessels over the insertion sites of horizontal rectus muscles, superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis, superficial punctate keratopathy, or infiltrate or ulceration from exposure keratopathy, afferent pupillary defect, dyschromatopsia, optic nerve swelling/pallor, and rarely choroidal folds.

Hyperthyroidism is common (at least 80% of patients with TED). Symptoms include a rapid pulse, hot and dry skin, diffusely enlarged thyroid gland (goiter), weight loss, muscle wasting with proximal muscle weakness, hand tremor, pretibial dermopathy or myxedema, cardiac arrhythmias, and change in bowel habits. Some patients are hypothyroid (5% to 10%) or euthyroid (5% to 10%). Euthyroid patients should undergo thyroid function testing (TFT) every 6 to 12 months; a significant proportion will develop thyroid abnormalities within 2 years. TED does not necessarily follow the associated thyroid dysfunction and may occur months to years before or after the thyroid dysfunction. The clinical progression of TED also has only a minor correlation with control of the thyroid dysfunction. A family history of thyroid dysfunction is common.

Concomitant myasthenia gravis with fluctuating double vision and ptosis may occur in a minority of patients. Always ask about bulbar symptoms (e.g., dysphagia, dysphonia, difficulty with breathing, weakness in proximal muscles, etc.) and fatigue in patients with suspected myasthenia gravis. The presence of ptosis (rather than upper eyelid retraction) or an adduction deficit in a patient with thyroid dysfunction and diplopia/external ophthalmoplegia should raise the possibility of myasthenia gravis (see 10.11, Myasthenia Gravis).

Differential Diagnosis of Upper Eyelid Retraction

Previous eyelid surgery or trauma may produce eyelid retraction or eyelid lag.

Severe contralateral ptosis may produce eyelid retraction because of Hering law, especially if the nonptotic eye is amblyopic.

Oculomotor nerve palsy with aberrant regeneration: The upper eyelid may elevate with downward gaze, simulating eyelid lag (pseudo-von Graefe sign). Ocular motility may be limited, but the results of forced duction testing and orbital imaging are normal. Eyelid retraction is typically accentuated in adduction or in downgaze. See 10.6, Aberrant Regeneration of the Third Cranial Nerve.

Parinaud syndrome: Eyelid retraction and limitation of upward gaze may accompany convergence-retraction nystagmus and mildly dilated pupils that react poorly to light with an intact near response (light-near dissociation).

History: Duration of symptoms? Pain? Change in vision? Known history of cancer or thyroid dysfunction? Smoker? Last mammogram, chest x-ray (especially in smokers), prostate examination/PSA level?

Complete ocular examination to evaluate for exposure keratopathy (slit-lamp examination with fluorescein staining) and optic nerve compression (afferent pupillary defect, dyschromatopsia, optic nerve edema, automated perimetry, OCT). Extraocular motility (versions and ductions). Diplopia is measured with prisms or Maddox rod (see Appendix 3, Cover/Uncover and Alternate Cover Tests and 10.7, Isolated Fourth Cranial Nerve Palsy). Proptosis is measured with a Hertel exophthalmometer. Check for resistance to retropulsion. Check IOP in both primary and upgaze (increase in upgaze correlates with severity of inferior rectus muscle enlargement in TED). Dilated fundus examination with optic nerve assessment.

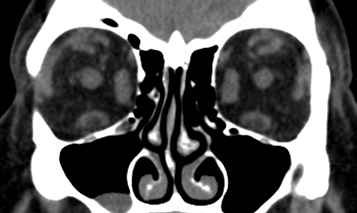

Imaging: CT of the orbit (axial and coronal views without contrast) is performed when the presentation is atypical (e.g., most cases of unilateral proptosis or any bilateral proptosis without upper eyelid retraction), or in the presence of severe congestive orbitopathy or optic neuropathy. CT in TED varies from patient to patient. In patients with restrictive strabismus and minimal proptosis (“myogenic variant”), imaging will show thickened EOMs without the involvement of the associated tendons and “apical crowding”—the loss of fat signal in the orbital apex because of enlarged EOMs (see Figure 7.2.1.2). In patients with full or nearly full extraocular motility, severe proptosis, and exposure keratopathy (“lipogenic variant”), increased fat volume with minimal muscle involvement is typical.

TFTs (T3, T4, and TSH). These may be normal. TSI and TPO may sometimes be ordered and can be followed over time, and recent evidence suggests a correlation with disease activity. An elevated TSI and TPO may help guide the clinician toward a diagnosis of TED in atypical cases and guide treatment (see below).

Serum vitamin D level. Recent studies have shown that a subnormal result increases the risk of progressive orbitopathy.

Workup for suspected myasthenia gravis is necessary in selected cases. See 10.11, Myasthenia Gravis.

Smoking cessation: All patients with TED who smoke must be explicitly told that continued tobacco use increases the risk of progression and the severity of orbitopathy. This conversation should be clearly documented in the medical record.

Consider teprotumumab (i.v. infusion of 10 mg/kg for the initial dose followed by an i.v. infusion of 20 mg/kg every 3 weeks for seven additional infusions).

Refer the patient to a medical internist or endocrinologist for management of systemic thyroid disease, if present. If TFTs are normal, the patient’s TFTs should be checked every 6 to 12 months. Not infrequently, a euthyroid patient with TED will have an elevated TSI and/or TPO.

Treat exposure keratopathy with artificial tears and lubrication or by taping eyelids closed at night (see 4.5, Exposure Keratopathy). Wearing swim goggles at night may be helpful. The use of topical cyclosporine or lifitegrast drops for the treatment of ocular surface inflammation in TED is still under investigation, but is a reasonable long-term treatment option if dry eye syndrome is present.

Treat eyelid edema with cold compresses in the morning and head elevation at night. This management may not be very effective. Avoid diuretics.

Indications for orbital decompression surgery include optic neuropathy, worsening or severe exposure keratopathy despite adequate treatment, globe luxation, uncontrollably high IOP, and morbid proptosis.

A stepwise approach is used for surgical treatment, starting with orbital decompression (if needed), followed by strabismus surgery (for significant strabismus, if present), followed by eyelid surgery. Alteration of this sequence may lead to unpredictable results. Note that only a minority of patients with TED will need to undergo the entire surgical algorithm.

Corticosteroids: During the acute inflammatory phase, prednisone 1 mg/kg p.o. daily, tapered over 4 to 6 weeks, is a reasonable temporizing measure to improve proptosis and diplopia in preparation for orbital decompression surgery. There is evidence that the use of a 12-week course of pulsed intravenous corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 500 mg i.v. weekly for 6 weeks, followed by 250 mg i.v. weekly for 6 weeks) followed by a course of oral corticosteroids may result in better long-term control of TED with fewer systemic side effects than oral corticosteroids and is a reasonable option to offer patients in the acute phase of TED. Other experts question the long-term efficacy of this regimen. Periorbital corticosteroid injections are also used by some experts, but may be inferior to oral corticosteroids. Chronic systemic corticosteroids for long-term management should be avoided because of the systemic side effects. If systemic corticosteroids are used, a detailed discussion of the potential short- and long-term risks should be documented. The patient should undergo a baseline dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry bone density scan and be started on vitamin D/calcium supplements and gastric prophylaxis with a proton pump inhibitor. Close follow-up with a primary care provider is also important for the management of blood sugar elevations and other side effects.

Orbital radiation: The use and efficacy of low-dose orbital radiation in the management of TED remain controversial. It may be used as a modality in the acute inflammatory phase of TED or to limit progression and provide long-term control. Radiation therapy appears to decrease the severity and progression of restrictive strabismus in patients with active TED; efficacy in managing other aspects of TED (including optic neuropathy) has not been proved definitively, but is advocated by some experts. Radiation therapy should be used with caution in patients with diabetes, as it may worsen diabetic retinopathy, and in vasculopaths, as it may increase the risk of radiation retinopathy or optic neuropathy, although neither of these risks have been proven definitively. All patients offered radiation therapy should be informed of the potential risks. If used, radiation is best performed according to strict protocols with carefully controlled dosage and shielding under the supervision of a radiation oncologist familiar with the technique. Typically, a total dose of 20 Gy is administered in 10 to 14 fractions over 2 weeks. Treatment may transiently exacerbate inflammatory changes and an oral prednisone taper may mitigate these symptoms. Improvement is often seen within a few weeks of treatment, but may take several months to attain the maximal effect.

Selenium supplementation: Data from Europe confirm that the use of selenium supplementation (an antioxidant) reduces the severity and progression of mild-to-moderate TED. It remains unclear whether this finding is applicable in the United States, where no dietary selenium deficiency (as is present in certain European countries) exists. It is reasonable to offer this therapy to women with mild-to-moderate, active TED at a dose of 100 μg p.o. b.i.d. for 6 months. Caution should be used in the use of selenium supplementation in men, especially with a family history of prostate cancer; some studies have suggested an increased risk of prostate cancer in males with high selenium levels, although this issue does not appear to have been settled conclusively.

Vitamin D supplementation: Recent evidence suggests that vitamin D deficiency may be a risk factor for TED. Vitamin D supplementation has been recommended with the hope of decreasing the risk of TED progression.

Biologics: Limited data are available on the use of biologic agents (e.g., rituximab, infliximab, adalimumab, etc.), with some studies showing efficacy and others finding none. With the exception of teprotumumab, their use as primary therapy in lieu of more conventional modalities is, at present, off-label and controversial. Furthermore, there appears to be little consensus as to the most effective, specific biologic target in TED. The use of teprotumumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibitor of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR), has been shown to be effective in the management of diplopia and exophthalmos from TED; its use for TED-associated optic neuropathy is under investigation. It is the only FDA-approved targeted therapy for patients with moderate to severe TED; the drug is effective in decreasing exophthalmos and diplopia. As with all biologics, teprotumumab has potential side effects which must be discussed with the patient in detail. A baseline hearing test with subsequent hearing testing as needed should be performed in all patients because of the potential for hearing loss and tinnitus from the therapy.

Visual loss from optic neuropathy: Treat immediately with prednisone 1 mg/kg/d with close monitoring. In cases of severe visual loss, admission for pulsed intravenous therapy may be indicated. Radiation therapy may be offered for mild-to-moderate optic neuropathy, with the understanding that there is typically a lag in the treatment effect. Posterior orbital decompression surgery (for mild-to-severe optic neuropathy), either medial or lateral, is essential and usually effective in rapidly reversing or stabilizing the optic neuropathy. Anterior orbital decompression is usually ineffective in treating TED optic neuropathy. Teprotumumab has also been shown to effectively manage optic neuropathy in TED based on small series of patients.

If thyroid ablation is necessary, thyroidectomy is much preferred to radioactive iodine in patients with TED.

Optic nerve compression requires immediate attention and close follow-up.

Patients with advanced exposure keratopathy and severe proptosis also require prompt attention and close follow-up.

Patients with minimal-to-no exposure problems and mild-to-moderate proptosis are re-evaluated every 3 to 6 months. Because of the potential risk of optic neuropathy, patients with restrictive strabismus may be followed more frequently.

Patients with fluctuating diplopia or ptosis should be evaluated for myasthenia gravis (see 10.11, myasthenia gravis).

All patients with TED are instructed to return immediately with any new visual problems, worsening diplopia, or significant ocular irritation. All smokers with TED must be reminded to discontinue smoking at every office visit, and appropriate referral to their primary physician for a smoking cessation program is indicated.

HeiselCJ, RidderingAL, AndrewsCA, KahanaA. Serum vitamin D deficiency is an independent risk factor for thyroid eye disease. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36(1):17–20.

SmithTJ, KahalyGJ, EzraDG, et al.Teprotumumab for thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1748–1761.

IDIOPATHIC ORBITAL INFLAMMATORY SYNDROME

SYNONYM: INFLAMMATORY ORBITAL PSEUDOTUMOR

May be acute, recurrent, or chronic. An explosive, painful onset is the hallmark of IOIS, but is present in only 65% of patients; the remainder may have a more insidious and relatively painless presentation. Pain, prominent red eye, “boggy” pink eyelid edema, double vision, or decreased vision. Children may have concomitant constitutional symptoms (fever, headache, vomiting, abdominal pain, and lethargy) and bilateral or sequential presentation, neither of which is typical in adults.

Proptosis and/or ocular motility restriction, usually unilateral, typically of explosive onset. On imaging studies, soft tissue anatomy is involved in varying degrees. The EOMs are thickened in cases of myositis; involvement of the tendon may occur, but is by no means essential or pathognomonic. The sclera (in posterior scleritis), Tenon capsule (in tenonitis), orbital fat, or lacrimal gland (in dacryoadenitis) may be involved. The paranasal sinuses are usually clear.

Boggy, pink eyelid erythema and edema, conjunctival injection and chemosis, lacrimal gland enlargement or a palpable orbital mass, decreased vision, uveitis, increased IOP, hyperopic shift (typically in posterior scleritis), optic nerve swelling or atrophy (uncommon), and chorioretinal folds.

Other noninfectious orbital inflammatory conditions: sarcoidosis, GPA, IgG4-related orbitopathy, amyloidosis, eosinophilic GPA, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, histiocytosis, etc.

Venolymphatic malformation (lymphangioma) with acute hemorrhage.

See 7.1, Orbital Disease, for general orbital workup.

History: Previous episodes? Any other systemic symptoms or diseases? History of cancer? Smoking? Last mammogram, chest x-ray, colonoscopy, prostate examination? History of breathing problems? A careful review of systems is warranted. Fever, night sweats, and weight loss?

Complete ocular examination, including color vision, extraocular motility, exophthalmometry, IOP, and dilated funduscopic evaluation.

Imaging: Orbital CT (axial, coronal, and parasagittal views) with contrast: may show a thickened posterior sclera (the “ring sign” of 360 degrees of scleral thickening), orbital fat or lacrimal gland involvement, or thickening of the EOMs (± their tendons). Bony erosion is very rare in IOIS and warrants further workup. Orbital MRI with contrast and fat suppression: May show EOM enlargement, infiltration of orbital fat, enlargement of the lacrimal gland, thickening of posterior Tenon/sclera, and enhancement along the optic nerve (perineuritis). In IOIS, the enhancement tends to “spill over” from an anatomic nidus into adjacent tissue (e.g., from EOM into surrounding orbital fat).

Blood tests may be obtained, but are often unremarkable: Westergren erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), CBC with differential, ANA, ACE, cANCA, pANCA, LDH, IgG4/IgG levels, SPEP, BUN/creatinine, fasting blood sugar, hemoglobin A1c, and interferon gamma–releasing assay (IGRA, QuantiFERON Gold) (Note: serologies should be obtained before instituting systemic corticosteroids). If sarcoidosis is suspected, consider chest CT, which is significantly more sensitive than chest x-ray. Mammography and prostate evaluation are warranted in specific or atypical cases.

If possible, perform an incisional biopsy of involved orbital tissue if easily accessible with minimal morbidity before instituting corticosteroid therapy (corticosteroid therapy may mask the true diagnosis). The lacrimal gland is often involved in IOIS and is relatively easy to access surgically; strong consideration should be given to biopsy all cases of suspected inflammatory dacryoadenitis. However, a biopsy of other orbital structures (EOM and orbital apex) is typically avoided in cases of classic IOIS because of the potential surgical risks; biopsy of these structures is reserved for atypical or recurrent cases. Always be suspicious of metastatic disease in any patient with a history of cancer.

Prednisone 1 to 1.2 mg/kg/d as an initial dose in adults and children, along with gastric prophylaxis (e.g., omeprazole 40 mg p.o. daily). All patients are warned about potential systemic side effects and are instructed to follow up with their primary physicians to monitor blood sugar and electrolytes (see 7.2.1, Thyroid Eye Disease for details on prescribing and managing systemic corticosteroids).

Low-dose radiation therapy may be used when the patient does not respond to systemic corticosteroids, when the disease recurs as corticosteroids are tapered, or when corticosteroids pose a significant risk to the patient. Radiation therapy should only be used once orbital biopsy, if anatomically and medically feasible, has excluded other etiologies.

Steroid-sparing agents (e.g., methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, etc.) in cases that do not respond to or recur with corticosteroid therapy. Biopsy of affected tissue, when feasible, is indicated to rule out malignancy.

Biologic therapy may be considered in cases that fail other modalities. The efficacy of specific biologic agents (e.g., CD20 depletion, tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α] antibody, etc.) in IOIS is not known. There is evidence that IOIS is a T-cell–driven process with elevated cytokines (including TNF-α); infliximab and adalimumab may be reasonable biologics to consider in recalcitrant or recurrent IOIS.

Re-evaluate in 1 to 2 days. Patients who respond dramatically to corticosteroids are maintained at the initial dose for 3 to 5 days, followed by 40 mg/d over 2 weeks, and an even slower taper below 20 mg/d, usually over several weeks. If the patient does not respond dramatically to appropriate corticosteroid doses, biopsy should be strongly considered. Recurrences of IOIS are not uncommon, especially at lower corticosteroid doses.