Lesions can range from focal to multifocal, unilateral or bilateral, and can be retinal, chorioretinal, or choroidal in location.

Associated vitreous cell, macular edema, retinal vasculitis.

Diagnostic Categories

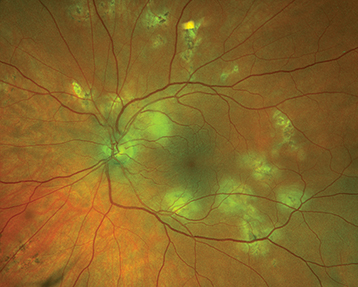

APMPPE: Acute visual loss in young adults, often after a viral illness. Multiple, creamy yellow-white or gray, plaque-like subretinal lesions in both eyes (see Figure 12.8.1). Lesions block early and stain late on IVFA. Usually spontaneously improves over weeks to months without treatment. May be associated with a cerebral vasculitis (consider MRA if the patient has a headache or other neurologic symptoms), in which case, systemic steroids are indicated.

MEWDS: Typically unilateral photopsias and visual loss, often after a viral illness and usually in young women. May have a shimmering scotoma. Uncommonly bilateral, sequential, or recurrent. Characterized by multiple, faint, small white lesions deep in the retina or at the level of the RPE with foveal granularity and occasionally vitreous cells. Fluorescein angiography may show a classic perifoveal “wreath-like” pattern. There is often an enlarged blind spot on formal visual field testing. Vision typically returns to normal within 6 to 8 weeks without treatment.

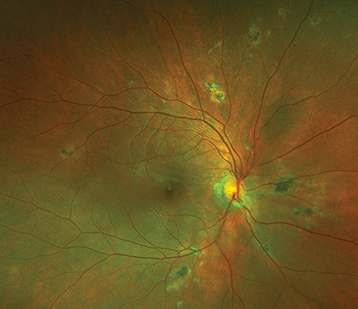

Birdshot chorioretinopathy: Usually middle-aged patients with multiple bilateral, oval, creamy-yellow spots deep to the retina, approximately 1 mm in diameter, scattered throughout the fundus but most prominent in the nasal quadrants (see Figure 12.8.2). A mild-to-moderate vitritis is typically present. Retinal vasculitis, CME, and optic nerve edema may be present. ICGA shows characteristic hypofluorescent spots. IVFA often shows retinal phlebitis and CME. Positive HLA-A29 in 95% to 100% of patients. Early systemic immunosuppression is often recommended.

MFC: Visual loss in young myopic women more often than men, typically bilateral. Multiple, small, round, and pale inflammatory lesions are located at the level of the pigment epithelium and choriocapillaris. Vitritis is a characteristic feature (unlike presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome). The lesions can occur in the macula and midperiphery and frequently respond to oral or periocular steroids, but typically recur with tapering. Immunosuppressive therapy is often necessary. CNV occurs in about one-third of patients, so patients should return for urgent evaluation if they have decreased vision or metamorphopsia (see Figure 12.8.3).

PIC: Blurred vision, paracentral scotoma, and/or photopsias, usually in young myopic women. Multiple, small round yellow-white spots predominantly in posterior pole with minimal intraocular inflammation. Typically bilateral. Lesions become well-demarcated atrophic scars within weeks. CNV may develop in up to 40% of patients (see Figure 12.8.4). Systemic immunosuppression is usually indicated.

Serpiginous choroiditis: Typically bilateral, recurrent chorioretinitis characterized by acute lesions (yellow-white subretinal patches with indistinct margins) bordering old atrophic scars. The chorioretinal changes usually extend from the optic disc outward; however, one-third may begin in the macula. Patients are typically aged 30 to 60 years. CNV may develop. Systemic immunosuppression is usually indicated. Must be distinguished from the “serpiginous” pattern of tuberculous chorioretinitis (see Figure 12.8.5).

Sarcoidosis: Pleomorphic uveitis. Posterior manifestations include focal or multifocal chorioretinal lesions that are initially creamy-appearing choroidal granulomas that progress to atrophic punched-out appearing lesions.

Syphilis: Pleomorphic uveitis. Must be ruled out in the setting of suspected MEWDS, APMPPE.

Toxoplasmosis: Classically an area of white retinitis adjacent to a prior chorioretinal scar (reactivation) but can be multifocal and bilateral.

TB: Pleomorphic uveitis. Must be ruled out in the setting of suspected serpiginous choroiditis as tuberculous serpinous-like choroiditis may present similarly.

Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome: Multifocal peripheral punched-out chorioretinal scars, peripapillary atrophy. Frequently complicated by CNV. Vitreous cells are absent. See 11.24, Ocular Histoplasmosis.