ORBITAL TUMORS IN CHILDREN

Proptosis or globe displacement.

See the specific etiologies for additional presenting signs. See Tables 7.4.1.1 and 7.4.1.2 for imaging characteristics.

TABLE 7.4.1.1: Childhood Orbital Lesions

| Well circumscribed | Dermoid cyst, rhabdomyosarcoma, optic nerve glioma, plexiform neurofibroma, and hemangioma of infancy |

| Diffuse and/or infiltrating | Lymphangioma, leukemia, IOIS, hemangioma of infancy, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, teratoma, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

TABLE 7.4.1.2: CT and MRI Characteristics of Pediatric Orbital Lesions

| MRI Features | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion | CT Characteristics | T1 Sequence | T2 Sequence |

| Dermoid or epidermoid cyst | A well-defined lesion that may mold to the bone of the orbital walls. On occasion, bony erosion is noted with the extension of the lesion intracranially or into the temporalis fossa (“dumbbell dermoid”). | Hypointense to fat, but usually hyperintense to vitreous. Only capsule enhances with gadolinium. Signal may increase if a large amount of viscous mucus (high protein-to-water ratio) is present within the lesion—an uncommon finding for most orbital masses and helpful in distinguishing this lesion from others | Iso- or hypointense to fat |

| Hemangioma of infancy | Irregular, contrast enhancing | Well defined, hypointense to fat, hyperintense to muscle | Hyperintense to fat and muscle |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | An irregular, well-defined lesion with possible bone destruction | Isointense to muscle | Hyperintense to muscle |

| Metastatic neuroblastoma | Poorly defined mass with bony destruction | — | — |

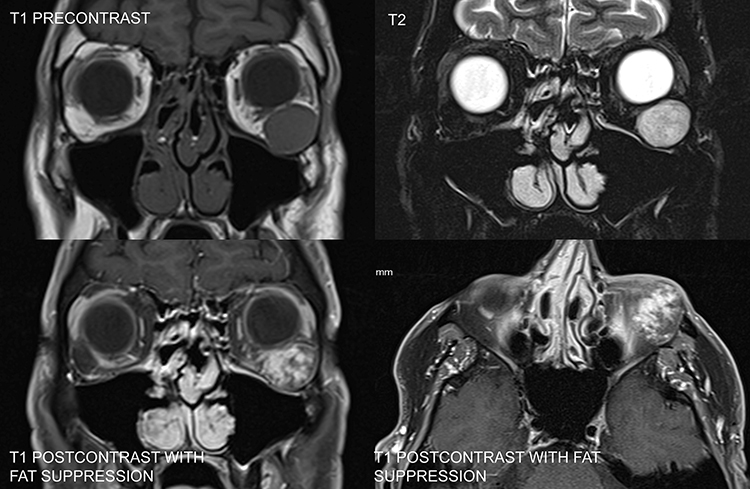

| Lymphangioma | Nonencapsulated irregular mass, “crabgrass of the orbit” | Cystic, possibly multiloculated, heterogeneous mass. Hypointense to fat, hyperintense to muscle, diffuse enhancement. May show signal of either acute or subacute hemorrhage (hyperintensity on T1) | Markedly hyperintense to fat and muscle |

| Optic nerve glioma | Fusiform enlargement of the optic nerve | Tubular or fusiform mass, hypointense to gray matter | Homogeneous hyperintensity |

| Plexiform neurofibroma | Diffuse, irregular soft tissue mass, possible defect in orbital roof | Iso- or slightly hyperintense to muscle | Hyperintense to fat and muscle |

| Leukemia (granulocytic sarcoma) | Irregular mass with occasional bony erosion | — | — |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Lytic defect, most commonly in superotemporal orbit or sphenoid wing | Isointense to muscle, good enhancement | — |

Orbital cellulitis from adjacent ethmoiditis: Most common cause of proptosis in children. It is of paramount importance to quickly rule out this etiology. See 7.3.1, Orbital Cellulitis.

Dermoid and epidermoid cysts: Manifest clinically from birth to young adulthood and enlarge slowly. Preseptal dermoid cysts may become symptomatic in childhood and are most commonly found in the temporal upper eyelid or brow, and less often in the medial upper eyelid. The palpable, smooth mass may be mobile or fixed to the periosteum. Posterior dermoids typically become symptomatic in adulthood and may cause proptosis or globe displacement. Dermoid cyst rupture may mimic orbital cellulitis. The B-scan US, when used, reveals a cystic lesion with good transmission of echoes. Because of the cystic configuration and specific signal properties, CT and MRI are usually diagnostic. See 14.3, Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Hemangioma of infancy (capillary hemangioma): Seen from birth to 2 years, generally show slow progressive growth over the first 6 to 9 months with slow involution thereafter. May be observed through the eyelid as a bluish mass or be accompanied by a red hemangioma of the skin (strawberry nevus, stork bite), which blanches with pressure (see Figure 7.4.1.1). Proptosis may be exacerbated by crying. It can enlarge over 6 to 12 months, but spontaneously regresses over the following several years. Not to be confused with the unrelated cavernous venous malformation (cavernous hemangioma) of the orbit, typically seen in adults.

Rhabdomyosarcoma: Average age of presentation is 8 to 10 years, but may occur from infancy to adulthood. May present with explosive proptosis, edema of the eyelids, a palpable eyelid lesion or subconjunctival mass, new-onset ptosis or strabismus, or a history of nosebleeds. Hallmarks are rapid onset and progression. Pain may occur in a minority of cases. Urgent biopsy and referral to a pediatric oncologist is warranted if suspected.

Metastatic neuroblastoma: Seen during the first few years of life (usually by the age of 5 years). Abrupt presentation with unilateral or bilateral proptosis, eyelid ecchymosis, and globe displacement. The child is usually systemically ill, and 80% to 90% of patients presenting with orbital involvement already have a known history of neuroblastoma. Note that metastatic neuroblastoma may also present as an isolated Horner syndrome in a child due to metastasis to the lung apex. Prognosis decreases with age.

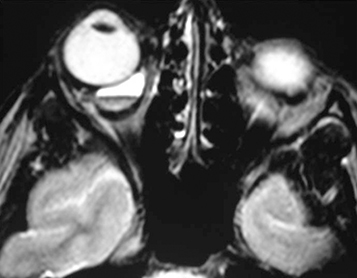

Venolymphatic malformation (lymphangioma): Usually seen in the first two decades of life with a slowly progressive course but may abruptly worsen if the tumor spontaneously bleeds. Proptosis may be intermittent and exacerbated by upper respiratory tract infections. Lymphangioma may present as an atraumatic eyelid ecchymosis. Concomitant conjunctival, eyelid, or oropharyngeal lymphangiomas may be noted (a conjunctival lesion appears as a multicystic mass). MRI is often diagnostic. The B-scan US, when used, often reveals cystic spaces. See Figure 7.4.1.2.

Optic nerve glioma (juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma): Usually first seen at the age of 2 to 6 years and is slowly progressive. The presentation includes painless axial proptosis with decreased visual acuity and a relative afferent pupillary defect. Optic nerve atrophy or swelling may be present. May be associated with neurofibromatosis (types I and II), in which case it may be bilateral. Prognosis decreases with chiasmal or hypothalamic involvement. See 13.11, Phakomatoses.

Plexiform neurofibroma: Seen in the first decade of life and is pathognomonic for neurofibromatosis type I. Ptosis, eyelid hypertrophy, S-shaped deformity of the upper eyelid, or pulsating proptosis (from the absence of the greater sphenoid wing) may be present. Facial asymmetry and a palpable anterior orbital mass may also be evident. See 13.11, Phakomatoses.

Leukemia (granulocytic sarcoma): Seen in the first decade of life with rapidly evolving unilateral or bilateral proptosis and, occasionally, swelling of the temporal fossa area due to a mass. Typically, granulocytic sarcoma precedes blood or bone marrow signs of leukemia (usually acute myelogenous leukemia) by several months. Any patient with a biopsy-proven granulocytic sarcoma of the orbit must be closely followed by an oncologist for leukemia development. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia can also produce unilateral or bilateral proptosis.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): May present in the orbit as a rapidly progressive mass with bony erosion on imaging. Three variants are encountered in the orbit: (1) multifocal, multisystem LCH (Letterer–Siwe disease) occurs in children <2 years old with an aggressive multisystem course and poor prognosis; (2) multifocal unisystem LCH (Hand–Schüller–Christian disease) occurs in children 2 to 10 years of age. The classic triad includes exophthalmos, lytic bone lesions, and diabetes insipidus from pituitary stalk infiltration; (3) unifocal LCH (eosinophilic granuloma) typically causes bony erosion in the superolateral orbit suggestive of malignancy. Occurs in older children and adults. Systemic progression occurs in only a minority of cases.

History: Determine the age of onset and the rate of progression. Does the proptosis vary (e.g., with crying or position)? Nosebleeds? Systemic illness? Fever? Weight loss? Recent upper respiratory infection? Purulent nasal discharge?

External examination: Look for an anterior orbital mass, a skin hemangioma, or a temporal fossa lesion. Measure any proptosis (Hertel exophthalmometer) or globe displacement. Refer to a pediatrician for abdominal examination to rule out mass or organomegaly.

Complete ocular examination, including visual acuity, pupillary assessment, color vision, IOP, refraction, and optic nerve evaluation. Check the conjunctival cul-de-sacs carefully.

Urgent imaging with either CT (axial, coronal, and parasagittal views) or MRI (with gadolinium-DTPA and fat suppression) of brain and orbits to rule out infection or neoplasia.

If paranasal sinus opacification is noted in the clinical setting of orbital inflammation, consider immediate systemic antibiotic therapy (see 7.3.1, Orbital Cellulitis).

In cases of acute onset and rapid progression with evidence of mass on imaging, an emergency incisional biopsy for frozen and permanent microscopic evaluation is indicated to rule out an aggressive malignancy (e.g., rhabdomyosarcoma).

Other tests as determined by the working diagnosis (usually performed in conjunction with a pediatric oncologist):

Rhabdomyosarcoma: Physical examination (look especially for enlarged lymph nodes), chest and bone radiographs, bone marrow aspiration, lumbar puncture, and liver function studies.

Neuroblastoma: Abdominal imaging (e.g., CT or MRI), urine for vanillylmandelic acid, radioiodinated metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy.

LCH: CBC with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum osmolarity, and skeletal survey.

Dermoid and epidermoid cysts: Complete surgical excision with the capsule intact. If the cyst ruptures, the contents can incite an acute inflammatory response.

Hemangioma of infancy: Observe if not causing visual obstruction, astigmatism, and amblyopia. All hemangiomas of infancy will eventually involute. In the presence of visual compromise (e.g., amblyopia and optic neuropathy), several treatment options exist:

Systemic β-blockers: While the exact mechanisms remain unclear, propranolol has become the preferred option in the treatment of refractory and rapidly proliferating infantile hemangiomas. Side effects of propranolol include hypoglycemia, hypotension, and bradycardia. Asthmatics and those with reactive airway disease are at risk for bronchospasm. Therefore, patients should be evaluated by a pediatrician pretreatment and monitored throughout the course of treatment. The initial dose of β-blocker is typically given in conjunction with cardiopulmonary monitoring. Note that not all lesions respond to this therapy.

Oral corticosteroids: Used less frequently since the introduction of β-blockers. The dose is 2 to 3 mg/kg, tapered over 6 weeks. IOP must be monitored, and patients should be placed on GI prophylaxis.

A local corticosteroid injection (e.g., betamethasone 6 mg/mL and triamcinolone 40 mg/mL) is seldom used. Care should be taken to avoid orbital hemorrhage and central retinal artery occlusion during injection. Skin atrophy and depigmentation are other potential complications. Note that periocular injection of triamcinolone is contraindicated by the manufacturer because of the potential risk of embolic infarction. See note in 6.7, Chalazion/Hordeolum.

Surgical excision: If the hemangioma is circumscribed and accessible, excision can be performed effectively and is often curative.

Interferon therapy: Usually reserved for large or systemic lesions that may be associated with a consumptive coagulopathy or high-output congestive heart failure (Kasabach–Merritt syndrome). There is a risk of spastic diplegia with this therapy. No longer used except in rare cases because of other viable alternatives, including propranolol.

Rhabdomyosarcoma: Managed by urgent biopsy and referral to a pediatric oncologist in most cases. Local radiation therapy and systemic chemotherapy are given once the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy and the patient has been appropriately staged. Significant orbital and ocular complications can occur even with prompt and aggressive management. Overall, the long-term prognosis for orbital rhabdomyosarcoma has greatly improved over the past 50 years due to advances in chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and exenteration is no longer the standard of care. Prognosis depends on the subtype of rhabdomyosarcoma, location of the lesion (orbital lesions have the best prognosis), and stage of the disease. Note that prognosis for orbital lesions worsens with spread to adjacent anatomy (paranasal sinuses or intracranial vault).

Venolymphatic malformation (lymphangioma): Most are managed by observation. Surgical debulking is performed for a significant cosmetic deformity, ocular dysfunction (e.g., strabismus and amblyopia), or compressive optic neuropathy from acute orbital hemorrhage, but may be difficult because of the infiltrative nature of the tumor. Incidence of hemorrhage into the lesion is increased after surgery. May recur after excision. Aspiration drainage of hemorrhagic cysts (“chocolate cysts”) may temporarily improve symptoms. Sclerosing therapy has become the most frequent management option for large, cystic lesions.

Optic nerve glioma: Controversial. Observation, surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy are used variably on a case-by-case basis.

Leukemia: Managed by a pediatric oncologist. Systemic chemotherapy for leukemia. Some physicians administer orbital radiation therapy alone in isolated orbital lesions (chloromas, granulocytic sarcomas) when systemic leukemia cannot be confirmed on bone marrow studies. However, patients need to be monitored closely for eventual systemic involvement.

Metastatic neuroblastoma: Managed by a pediatric oncologist in most cases. Local radiation and systemic chemotherapy.

Plexiform neurofibroma: Surgical excision is reserved for patients with significant symptoms or disfigurement. The lesions tend to be vascular, infiltrative, and recurrent.

LCH: Therapy depends on the extent of the disease. Multisystem involvement requires chemotherapy. With unifocal involvement (eosinophilic granuloma in adults), debulking and curettage are usually curative.

Tumors with rapid onset and progression require urgent attention, with appropriate and timely referral to a pediatric oncologist when necessary.

Tumors that progress more slowly may be managed less urgently.

ORBITAL TUMORS IN ADULTS

Prominent eye, double vision, and decreased vision, may be asymptomatic.

Proptosis, pain, displacement of the globe away from the location of the tumor, orbital mass on palpation, or mass found with neuroimaging. Specific tumors may cause enophthalmos secondary to orbital fibrosis.

A palpable mass, extraocular motility limitation, orbital inflammation, optic disc edema or atrophy, and choroidal folds may be present. See the individual etiologies for more specific findings. See Tables 7.4.2.1 and 7.4.2.2 for imaging characteristics.

TABLE 7.4.2.1: CT and MRI Characteristics of Selected Adult Orbital Lesions

| MRI Features | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion | CT Characteristics | T1 Sequence | T2 Sequence |

| Metastasis | Poorly defined mass conforming to orbital structure; possible bony erosion | Infiltrating mass; hypointense to fat, isointense to muscle; moderate-to-marked enhancement | Hyperintense to fat and muscle |

| Lymphoid tumors (Figure 7.6.1C) | Irregular mass molding to the shape of orbital bones or globe; bone destruction possible in aggressive lesions and HIV | Irregular mass; hypointense to fat, iso- or hyperintense to muscle; moderate-to-marked enhancement | Hyperintense to muscle |

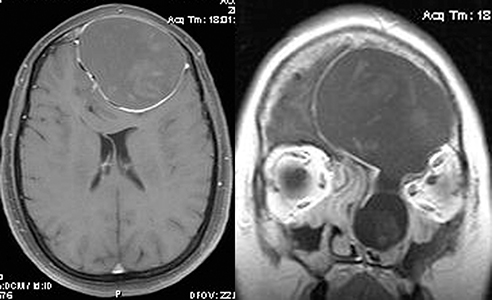

| Cavernous venous malformation (Figure 7.4.2.1.) | Encapsulated mass typically within the muscle cone | Iso- or hyperintense to muscle; delayed, heterogeneous, and diffuse enhancement | Hyperintense to muscle and fat |

| Optic nerve sheath meningioma | Calcification may be present. Enhancement with contrast | Three patterns may be seen: fusiform, tubular, and globular; marked enhancement of lesion with gadolinium with sparing of the optic nerve parenchyma | The typical cuff of CSF around the optic nerve may be effaced by the tumor |

| Mesenchymal tumors (e.g., SFT) | Well-defined mass anywhere in the orbit | Heterogeneous mass; hypointense to fat, hyper- or isointense to muscle; moderate diffuse or irregular enhancement. May have vascular flow voids | Variable |

| Neurilemmoma | Fusiform or ovoid mass often in the superior orbit | Iso- or hyperintense to muscle with variable enhancement | Variable intensity |

| Neurofibroma | Diffuse, irregular soft tissue mass; a possible defect in orbital roof | Iso- or slightly hyperintense to muscle | Hyperintense to fat and muscle |

TABLE 7.4.2.2: CT and MRI Characteristics of Select Adult Extraconal Orbital Lesions

| Mucocele (Figure 7.4.2.2) | Frontal or ethmoid sinus cyst that extends into orbit | Variable from hypo- to hyperintense, depending on the protein content/viscosity of the lesion | Hyperintense to fat |

| Localized neurofibroma | Well-defined mass in superior orbit | Well-circumscribed, heterogeneous; iso- or hyperintense to muscle | Hyperintense to fat and muscle |

Primarily intraconal/optic nerve:

Cavernous venous malformation (cavernous hemangioma): Most common benign orbital mass in adults. Middle-aged women most commonly affected, with a slow onset of orbital signs. Growth may accelerate during pregnancy (see Figure 7.4.2.1).

Mesenchymal tumors: Orbital lesions with varying degrees of aggressive behavior. The largest group is now labeled SFT and includes fibrous histiocytoma and hemangiopericytoma. These lesions cannot be accurately distinguished clinically or radiographically. May occur at any age. Immunohistochemical staining for STAT6 is usually diagnostic.

Neurilemmoma (schwannoma): Progressive, painless proptosis. Rarely associated with neurofibromatosis type II. Malignant schwannoma has been reported but is rare.

Neurofibroma: See 7.4.1, Orbital Tumors in Children.

Meningioma: Optic nerve sheath meningioma (ONSM) typically occurs in middle-aged women with painless, slowly progressive visual loss, often with mild proptosis. An afferent pupillary defect may be present. Ophthalmoscopy can reveal optic nerve swelling, optic atrophy, or abnormal collateral vessels around the optic nerve head (optociliary shunts).

Other optic nerve lesions: Optic nerve glioma, optic nerve sarcoid, malignant optic nerve glioma of adulthood (MOGA). The second most common lesion of the optic nerve (excluding optic neuritis) after ONSM is optic nerve sarcoid, which may be difficult to distinguish from ONSM clinically and radiologically. The ACE level may be normal in cases of isolated optic nerve sarcoid. MOGA is a rapidly progressive optic nerve lesion of the elderly akin to World Health Organization grade IV glioblastoma multiforme; it carries a poor prognosis and is often misdiagnosed as a “progressive NAION.”

Venolymphatic malformation (lymphangioma): Usually discovered in childhood. See 7.4.1, Orbital Tumors in Children.

Mucocele: Often presents with a frontal headache and a history of chronic sinusitis or sinus trauma. Usually located nasally or superonasally, emanating from the frontal and ethmoid sinuses. See Figure 7.4.2.2.

Localized neurofibroma: Occurs in young to middle-aged adults with the slow development of orbital signs. Eyelid infiltration results in an S-shaped upper eyelid. Some have neurofibromatosis type I, but most do not.

SPA or spontaneous hematoma: See 7.3.2, Subperiosteal Abscess.

Dermoid cyst: See 7.4.1, Orbital Tumors in Children.

Others: Tumors of the lacrimal gland (pleomorphic adenoma [well circumscribed], adenoid cystic carcinoma [ACC] [variably circumscribed with adjacent bone destruction]), sphenoid wing meningioma (commonly occurring in middle-aged females and a cause of compressive optic neuropathy), secondary tumors extending from the brain or paranasal sinuses, primary osseous tumors, and vascular lesions (e.g., varix and arteriovenous malformation including CCF).

Lymphoproliferative disease (lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoma): More commonly extraconal. About 50% are well circumscribed on imaging, and 50% are infiltrative. Ocular adnexal lymphoma is typically of the non-Hodgkin B-cell type (NHL), and about 75% to 85% follow an indolent course (extranodal marginal zone lymphoma [EMZL] or mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT] lymphoma, grade I or II follicular cell lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [small cell lymphoma]). The remainder are aggressive lesions (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma, among others). May occur at any adult age; orbital NHL is rare in children. Slow onset and progression unless there is an aggressive subtype. Pain may occur in up to 25% of orbital NHL. Typically develops superiorly in the anterior aspect of the orbit, with about 50% occurring in the lacrimal gland. May be accompanied by a subconjunctival salmon-colored lesion. Most orbital NHL (especially if indolent subtype) occurs without evidence of systemic lymphoma (Stage IE). Orbital NHL may be confused with IOIS, especially when it presents more acutely with pain. Note that NHL frequently responds dramatically to systemic corticosteroids, as does IOIS.

Metastases: Usually occurs in middle-aged to elderly people with a variable onset of orbital signs. Common primary sources include the breast (most common in women), lung (most common in men), and genitourinary tract (especially prostate). Twenty percent of orbital breast cancer metastases are bilateral and frequently involve EOMs. Enophthalmos (not proptosis) may be seen with scirrhous breast carcinoma. Metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma has a propensity for bone and often involves the zygoma or greater sphenoid wing. Note that uveal metastases are far more common than orbital lesions by a 10 to 1 ratio.

History: Determine the age of onset and rate of progression. Headache or chronic sinusitis? History of cancer? Trauma (e.g., mucocele, hematocele, orbital foreign body, or ruptured dermoid)? Classic lymphoma B symptoms including fever, night sweats, or unintentional weight loss.

Complete ocular examination, particularly visual acuity, pupillary response, ocular motility, dyschromatopsia testing, an estimate of globe displacement and proptosis (Hertel exophthalmometer), IOP, optic nerve evaluation, and automated perimetry of each eye if concerned about an optic neuropathy. Examine conjunctival surface and cul-de-sacs carefully for salmon patches if lymphoma is suspected.

CT (axial, coronal, and parasagittal views) of the orbit and brain or orbital MRI with fat suppression/gadolinium, depending on suspected etiology and age. See 14.2, Computed Tomography and 14.3, Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Orbital US with color Doppler imaging as needed to define the vascularity of the lesion. Conventional B-scan US has a limited role in the diagnosis of orbital pathology because of the availability and resolution of CT and MRI, but may provide some data on anterior orbital lesions.

When a metastasis is suspected and the primary tumor is unknown, the following should be performed:

Incisional biopsy to confirm the diagnosis, with estrogen receptor assay if breast adenocarcinoma is suspected.

Breast examination and palpation of axillary lymph nodes by the primary physician.

Medical workup (e.g., chest imaging, mammogram, prostate examination, PSA testing, and colonoscopy).

If the patient has a known history of metastatic cancer and is either a poor surgical candidate or has an orbital lesion that is difficult to access, empiric therapy for the orbital metastasis is a reasonable option.

If lymphoproliferative disease (lymphoma or lymphoid hyperplasia) is suspected, a biopsy for definitive diagnosis is indicated. Include adequate fixed tissue (for permanent sectioning and immunohistochemistry) and fresh tissue (for flow cytometry). If lymphoproliferative disease is confirmed, the systemic workup is almost identical for polyclonal (lymphoid hyperplasia) and monoclonal (lymphoma) lesions (e.g., CBC with differential, SPEP, LDH, and whole-body imaging [CT/MRI or positron emission tomography/CT]). Based on recent data, bone marrow biopsy is indicated in all cases of orbital lymphoma, even indolent subtypes. Close surveillance with serial clinical examination and systemic imaging is indicated over several years in all patients with lymphoproliferative disease, regardless of clonality. A significant percentage of patients initially diagnosed with orbital lymphoid hyperplasia will eventually develop systemic lymphoma.

Metastatic disease: Systemic chemotherapy as required for the primary malignancy. Radiation therapy is often used for palliation of the orbital mass; high-dose radiation therapy may result in ocular and optic nerve damage. Hormonal therapy may be indicated in certain cases (e.g., breast and prostate adenocarcinoma).

Well-circumscribed lesions: Complete surgical excision is performed when there is compromised visual function, diplopia, rapid growth, or high suspicion of malignancy. Excision for cosmesis can be offered if the patient is willing to accept the surgical risks. An asymptomatic patient can be followed every 6 to 12 months with serial examinations and imaging (and if remains stable, with decreasing frequencies). Progression of symptoms and rapidly increasing size on serial imaging are indications for exploration and biopsy/excision.

Mucocele: Systemic antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin/sulbactam 3 g i.v. q6h) followed by surgical drainage of the mucocele, usually by transnasal endoscopic technique. Orbitotomy for excision is usually unnecessary and contraindicated in most cases as disruption of the mucocele’s mucosal lining may lead to recurrent, loculated lesions.

Lymphoid tumors: Lymphoid hyperplasia and indolent lymphoma without systemic involvement are treated almost identically. With few exceptions, orbital lymphoproliferations respond dramatically to relatively low doses of radiation (∼24 Gy); ocular and optic nerve complications are therefore less common than with other malignancies. Systemic lymphoma or localized aggressive lymphoma are treated with chemotherapy and in many cases with biologics (e.g., rituximab). The vast majority of orbital lymphoma is of B-cell origin and 50% to 60% are EMZL. In older individuals with few symptoms and indolent lesions, more conservative measures may be indicated, including observation alone or brief courses of corticosteroids. To date, there is no clear role for the use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of orbital lymphoproliferative disease except possibly in certain geographic locations. There is also no clear evidence that orbital EMZL is in any way related to Helicobacter pylori-associated gastric EMZL. Remember that the specific subtype of NHL (and therefore level of aggressiveness) and stage of the disease define the ultimate treatment.

ONSM: The diagnosis is usually based on slow progression and typical MRI findings. MRI with gadolinium is the preferred imaging modality. CT is occasionally helpful in demonstrating intralesional calcifications. Empiric stereotactic radiation therapy is usually indicated when the tumor is growing and causing significant visual loss. Otherwise, the patient may be followed every 3 to 6 months with serial clinical examinations and imaging studies as needed. Recent studies have shown the significant efficacy of stereotactic radiotherapy in decreasing tumor growth and in visual preservation. Stereotactic radiotherapy is not equivalent to gamma knife therapy (“radiosurgery”). Empiric stereotactic radiotherapy (i.e., without confirmatory biopsy) is a reasonable treatment option, but is reserved for typical cases of ONSM. Atypical or rapidly progressive lesions still require biopsy.

Localized neurofibroma: Surgical removal is performed for symptomatic and enlarging tumors. Excision may be difficult and incomplete in infiltrating neurofibromas.

Neurilemmoma: Same as for cavernous venous malformation (see above).

Mesenchymal tumors (usually SFT): Complete excision when possible. The lesion may be fixed to the surrounding normal anatomy and abut critical structures. In such cases, debulking is reasonable, with long-term follow-up and serial imaging to rule out aggressive recurrence or potential malignant transformation. SFT is notoriously difficult to prognosticate. Some lesions will behave in an indolent fashion, while others may present with aggressive recurrence, regional extraorbital extension, or systemic spread.

In cases of isolated lesions that can be completely excised (e.g., cavernous venous malformation), routine ophthalmologic follow-up is all that is necessary.

Other etiologies require long-term follow-up at variable intervals.

See 7.6, Lacrimal Gland Mass/Chronic Dacryoadenitis, especially if the mass is in the outer one-third of the upper eyelid, and see 7.4.1, Orbital Tumors in Children. |

OlsenTG, HolmF, MikkelsenLH, et al.Orbital lymphoma: an international multicenter retrospective study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;199:44–57.

RoseGE, GoreSK, PlowmanNP. Cranio-orbital resection does not appear to improve survival of patients with lacrimal gland carcinoma. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35:77–84.