ORBITAL CELLULITIS

Red eye, pain, blurred vision, double vision, eyelid and/or periorbital swelling, nasal congestion/discharge, sinus headache/pressure/congestion, tooth pain, infra- and/or supraorbital pain, or hypesthesia.

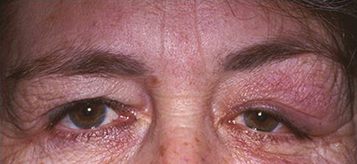

(See Figures 7.3.1.1 and 7.3.1.2.)

Eyelid edema, erythema, warmth, and tenderness. Conjunctival chemosis and injection, proptosis, and restricted extraocular motility with pain on attempted eye movement are usually present. Signs of optic neuropathy (e.g., afferent pupillary defect and dyschromatopsia) may be present in severe cases.

Decreased vision, retinal venous congestion, optic disc edema, purulent discharge, decreased periorbital sensation, and fever. CT scan usually shows adjacent sinusitis (typically at least an ethmoid sinusitis) and possibly a subperiosteal orbital collection.

See 7.1, Orbital Disease.

Direct extension from a paranasal sinus infection (especially ethmoiditis), focal periorbital infection (e.g., infected hordeolum, dacryoadenitis, dacryocystitis, and panophthalmitis), or dental infection.

Sequela of orbital trauma (e.g., orbital fracture, penetrating trauma, and retained intraorbital foreign body).

Sequela of other ocular surgery or intraocular infection (e.g., panophthalmitis) (less common).

Vascular extension (e.g., seeding from a systemic bacteremia or locally from facial cellulitis via venous anastomoses).

In cases of unsuspected retained foreign body, cellulitis may develop months after injury (see 3.22, Intraorbital Foreign Body). |

Adult: Staphylococcus species, Streptococcus species, and Bacteroides species.

Children: Haemophilus influenzae (rare in vaccinated children).

Immunocompromised patients (diabetes, chemotherapy, and HIV infection): Fungi including those that produce zygomycosis infections (e.g., Mucor) and Aspergillus.

See 7.1, Orbital Disease, for a nonspecific orbital workup.

History: Trauma or surgery? Ear, nose, throat, or systemic infection? Tooth pain or recent dental abscess? Stiff neck or mental status changes? Diabetes or an immunosuppressive illness? Use of immunosuppressive agents?

Complete ophthalmic examination to evaluate for orbital signs including afferent pupillary defect, restriction or pain with ocular motility, proptosis, increased resistance to retropulsion, elevated IOP, decreased color vision, decreased skin sensation, or an optic nerve or fundus abnormality.

Check vital signs, mental status, and neck flexibility. Check for preauricular or cervical lymphadenopathy. Evaluate nasal passages for signs of eschar/fungal involvement in diabetic, acidotic, or immunocompromised patients.

Imaging: CT scan of the orbits and paranasal sinuses (axial, coronal, and parasagittal views, with contrast if possible) to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out a retained foreign body, orbital or SPA, paranasal sinus disease, cavernous sinus thrombosis, or intracranial extension. If superior ophthalmic vein or cavernous sinus thrombosis are suspected clinically, MRI with contrast and fat suppression should be obtained.

Laboratory studies: CBC with differential and blood cultures.

Explore and debride any penetrating wound, if present, and obtain a Gram stain and culture of any drainage (e.g., blood and chocolate agars, Sabouraud dextrose agar, and thioglycolate broth). Obtain CT before wound exploration to rule out skull base foreign body.

Consult neurosurgery for suspected meningitis for management and possible lumbar puncture. If paranasal sinusitis is present, consider a consultation with otorhinolaryngology for possible surgical drainage. Consider an infectious disease consultation in atypical, severe, or unresponsive cases. If a dental source is suspected, oral maxillofacial surgery should be consulted urgently for assessment, since infections from this area tend to be aggressive, potentially vision threatening, and may spread into the cavernous sinus.

Zygomycosis is an orbital, nasal, and sinus disease occurring in diabetic or otherwise immunocompromised patients. Typically associated with severe pain and external ophthalmoplegia. Profound visual loss may rapidly occur. Metabolic acidosis may be present. Sino-orbital zygomycosis is rapidly progressive and life threatening. See 10.10, Cavernous Sinus and Associated Syndromes (Multiple Ocular Motor Nerve Palsies). |

Admit the patient to the hospital and consider consult with an infectious disease specialist and otorhinolaryngologist.

Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics to cover Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms are recommended for 48 to 72 hours, followed by oral medication for at least 1 week. The specific antibiotic agents vary.

In patients from the community with no recent history of hospitalization, nursing home stay, or institutional stay, we currently recommend ampicillin–sulbactam 3 g i.v. q6h for adults; 300 mg/kg per day in four divided doses for children, a maximum daily dose of 12 g ampicillin–sulbactam (8 g ampicillin component);

piperacillin–tazobactam 4.5 g i.v. q8h or 3.375 g q6h for adults; 240 mg of piperacillin component/kg/d in three divided doses for children, and a maximum daily dose of 18 g piperacillin.

In patients suspected of harboring hospital-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (HA-MRSA) or in those with suspected meningitis, add concurrent intravenous vancomycin at 15 to 20 mg/kg q8–12h for adults with normal renal function and 40 to 60 mg/kg/d in three or four divided doses for children, with a maximum daily dose of 2 g. For adults who are allergic to penicillin but can tolerate cephalosporins, use vancomycin as dosed above plus: Ceftriaxone 2 g i.v. daily and metronidazole 500 mg i.v. q8h (not to exceed 4 g/d).

For adults who are allergic to penicillin/cephalosporin, treat with a combination of a fluoroquinolone (for patients >17 years of age, moxifloxacin 400 mg i.v. daily or ciprofloxacin 400 mg i.v. q12h or levofloxacin 750 mg i.v. daily) and metronidazole 500 mg i.v. q8h.

Nasal decongestant spray as needed for up to 3 days. Nasal corticosteroid spray may also be added to quicken the resolution of sinusitis.

Erythromycin or bacitracin ointment q.i.d. for corneal exposure and chemosis if needed.

If the orbit is tight, an optic neuropathy is present, or the IOP is severely elevated, immediate canthotomy/cantholysis may be needed. See 3.20, Traumatic Retrobulbar Hemorrhage (Orbital Hemorrhage) for indications and technique.

The use of systemic corticosteroids in the management of orbital cellulitis remains controversial. If systemic corticosteroids are considered, it is probably safest to wait 24 to 48 hours until an adequate intravenous antibiotic load has been given (three to four doses). Studies of pediatric orbital cellulitis with or without abscess found that the concomitant use of systemic corticosteroids with antibiotics shortened the length of intravenous antibiotic therapy and hospital stay. Serial C-reactive protein (CRP) measurements may be helpful in determining a threshold for corticosteroid use (see Follow-Up below).

Re-evaluate at least twice daily in the hospital for the first 48 hours. Severe infections may require multiple daily examinations. Clinical improvement may take 24 to 36 hours.

Examine the retina and optic nerve for signs of posterior compression (e.g., chorioretinal folds), inflammation, or exudative retinal detachment.

If orbital cellulitis is clearly and consistently improving, then the regimen can be changed to oral antibiotics (depending on the culture and sensitivity results) to complete a 10- to 14-day course. We often use:

Amoxicillin/clavulanate: 25 to 45 mg/kg/d p.o. in two divided doses for children and a maximum daily dose of 90 mg/kg/d; 875 mg p.o. q12h for adults;

Cefpodoxime: 10 mg/kg/d p.o. in two divided doses for children and a maximum daily dose of 400 mg; 200 mg p.o. q12h for adults;

If CA-MRSA is suspected, recommended oral treatment regimens include doxycycline 100 mg p.o. q12h (not in pregnant or nursing women and not in children younger than 8 years), one to two tablets trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800 mg p.o. q12h, clindamycin 450 mg p.o. q6h, or linezolid 600 mg p.o. b.i.d. (only with approval from an infectious disease specialist, given current low resistance).

The patient is examined every few days as an outpatient until the condition resolves and instructed to return immediately with worsening signs or symptoms.

If clinical deterioration is noted after an adequate antibiotic load (three to four doses), a CT scan of the orbit and brain with contrast should be repeated to look for abscess formation (see 7.3.2, Subperiosteal Abscess). If an abscess is found, surgical drainage may be required. Because radiographic findings may lag behind the clinical examination, clinical deterioration may be the only indication for surgical drainage. Other conditions that should be considered when the patient is not improving include cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, resistant organism (HA-MRSA, CA-MRSA), aggressive organism (often from an undiagnosed odontogenic source), or a noninfectious etiology. |

SUBPERIOSTEAL ABSCESS

Similar to orbital cellulitis, though may be magnified in scale. Suspect an SPA if a patient with orbital cellulitis fails to improve or deteriorates after 48 to 72 hours of intravenous antibiotics.

Intraorbital abscess: Rare because the periorbita is an excellent barrier to intraorbital spread. May be seen following penetrating trauma, previous surgery, retained foreign body, extrascleral extension of endophthalmitis, extension of SPA, or from endogenous seeding. Treatment is surgical drainage and intravenous antibiotics. Drainage may be difficult because of several isolated loculations.

Cavernous sinus thrombosis: Rare in the era of antibiotics. Most commonly seen with zygomycosis (i.e., mucormycosis) (see 10.10, Cavernous Sinus and Associated Syndromes [Multiple Ocular Motor Nerve Palsies]). In bacterial cases, the patient is usually also septic and may be obtunded and hemodynamically unstable. Dental infections have a propensity for aggressive behavior and may spread along the midfacial and skull base venous plexuses into the cavernous sinus. MRI is more sensitive than CT in diagnosing the thrombus. Prognosis is guarded in all cases. Manage with hemodynamic support (possibly in an intensive care unit), broad-spectrum antibiotics, and surgical drainage if an infectious nidus is identified (e.g., paranasal sinuses, tooth abscess, and orbit). Anticoagulation can be considered to limit the propagation of the thrombosis into the central venous sinuses; anticoagulant therapy is typically managed by the neurology team.

See 7.3.1, Orbital Cellulitis, for workup. In addition:

Obtain CT with contrast, which allows for easier identification and extent of an abscess. In cases of suspected cavernous sinus thrombosis, discuss with the radiologist before CT, since special CT techniques and windows may help with diagnosis. MRI may also be indicated in cases of cavernous sinus thrombosis, skull base spread of infection and meningitis.

All orbital cellulitis patients who do not improve after 48 to 72 hours of intravenous antibiotic therapy should undergo repeat imaging. |

Microbes involved in SPA formation vary and are to a degree related to the age of the patient. The causative microbes influence response to intravenous antibiotics and the need for surgical drainage. See Table 7.3.2.1.

TABLE 7.3.2.1: Age and Subperiosteal Abscess

Age (y) Cultures Need to Drain <9 Sterile (58%) or single aerobe No in 93% 9 to 14 Mixed aerobe and anaerobe ± >14 Mixed, anaerobes in all Yes From Harris GJ. Subperiosteal abscess of the orbit: older children and adults require aggressive treatment. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17(6):395–397.

Leave an orbital drain in place for 24 to 48 hours to prevent abscess reformation.

Intracranial extension necessitates neurosurgical involvement.

Expect dramatic and rapid improvement after adequate drainage. Additional imaging, exploration, and drainage may be indicated if improvement does not occur rapidly.

Do not reimage immediately unless the patient is deteriorating postoperatively. Imaging usually lags behind clinical response by at least 48 to 72 hours.

ACUTE DACRYOADENITIS: INFECTION/INFLAMMATION OF THE LACRIMAL GLAND

Unilateral pain, redness, and swelling over the outer one-third of the upper eyelid, often with tearing or discharge. Typically occurs in children and young adults.

(See Figures 7.3.3.1 and 7.3.3.2.)

Erythema, swelling, and tenderness over the outer one-third of the upper eyelid. May be associated with hyperemia of the palpebral lobe of the lacrimal gland, S-shaped upper eyelid.

Ipsilateral preauricular lymphadenopathy, ipsilateral conjunctival chemosis temporally, fever, and elevated WBC.

Hordeolum: Tender eyelid nodule from the blocked gland. See 6.7, Chalazion/Hordeolum.

Preseptal cellulitis: Erythema and warmth of the eyelids and the surrounding soft tissue. See 6.9, Preseptal Cellulitis.

Orbital cellulitis: Proptosis and limitation of ocular motility often accompany eyelid erythema and swelling. See 7.3.1, Orbital Cellulitis.

IOIS involving the lacrimal gland: May have concomitant proptosis, downward displacement of the globe, or limitation of extraocular motility. Typically afebrile with a normal WBC. Does not respond to antibiotics but improves dramatically with systemic steroids. See 7.2.2, Idiopathic Orbital Inflammatory Syndrome.

Leaking dermoid cyst: Dermoid cysts often occur either superolaterally or superomedially. Leakage causes an intense and acute inflammatory reaction.

Rhabdomyosarcoma: Most common pediatric orbital malignancy. Rapid presentation, but pain and erythema occur in only a minority of cases. See 7.4.1, Orbital Tumors in Children.

Primary malignant lacrimal gland tumor or lacrimal gland metastasis: Commonly produces a displacement of the globe or proptosis. May present with an acute inflammatory clinical picture, but more often presents as a subacute process. Pain is common secondary to perineural spread along sensory nerves. Often palpable, evident on CT scan. See 7.6, Lacrimal Gland Mass/Chronic Dacryoadenitis.

Retained foreign body, with a secondary infectious or inflammatory process. The patient may not remember any history of penetrating trauma.

Inflammatory, noninfectious: By far the most common. A more indolent and painless course is seen in lymphoproliferation, sarcoidosis, IgG4-related disease, etc. More acute and painful presentation in IOIS.

Bacterial: Less common. Usually due to S. aureus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, or streptococci.

Viral: Seen in mumps, infectious mononucleosis, influenza, and varicella zoster. May result in severe dry eye due to lacrimal gland fibrosis. Usually bilateral.

The following is performed when an acute etiology is suspected. When the disease does not respond to medical therapy or another etiology is being considered, see 7.6, Lacrimal Gland Mass/Chronic Dacryoadenitis.

History: Acute or chronic? Fever? Discharge? Systemic infection or viral syndrome?

Complete ocular examination, particularly extraocular motility assessment.

Examine the parotid glands (often enlarged in mumps, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, lymphoma, and syphilis).

Perform a CT scan of the orbit (axial, coronal, and parasagittal views), preferably with contrast (see Figure 7.3.3.3). CT allows for better assessment than MRI of the adjacent bony detail, but MRI provides better detail of sensory nerves and skull base anatomy.

If the patient is febrile, a CBC with differential and blood cultures are obtained.

If the specific etiology is unclear, it is best to empirically treat the patient with systemic antibiotics (see bacterial etiology below) for 24 hours with careful clinical reassessment. The clinical response to antibiotics can guide further management and direct one toward a specific etiology.

For treatment, see 7.2.2, Idiopathic Orbital Inflammatory Syndrome. Most often corticosteroid therapy is used. However, preliminary evidence suggests a role for therapeutic debulking and local corticosteroid injection at the time of diagnostic biopsy in improving outcomes and decreasing recurrence.

Bacterial or infectious (but unidentified) etiology:

If moderate to severe, hospitalize and treat as per 7.3.1, Orbital Cellulitis.

Aspirin is contraindicated in young children with a viral syndrome because of the risk of Reye syndrome. |

Daily until improvement is confirmed. In patients who fail to respond to antibiotic therapy, judicious use of oral prednisone (see 7.2.2, Idiopathic Orbital Inflammatory Syndrome) is reasonable, as long as close follow-up is maintained. Inflammatory dacryoadenitis should respond to oral corticosteroid therapy within 48 hours. Watch for signs of orbital involvement, such as decreased extraocular motility or proptosis, which requires hospital admission for intravenous antibiotic therapy and close monitoring. See 7.6, Lacrimal Gland Mass/Chronic Dacryoadenitis.