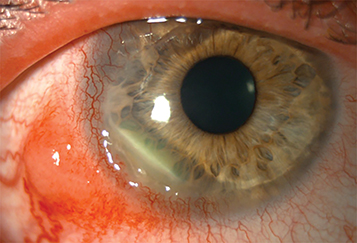

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK), idiopathic or related to systemic connective tissue disease: Rheumatoid arthritis, GPA, relapsing polychondritis, polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus, others. Peripheral (unilateral or bilateral) corneal thinning/ulcers may be associated with sterile inflammatory infiltrates. The sclera may be involved. May progress circumferentially to involve the entire peripheral cornea. Perforation may occur. This may be the first manifestation of systemic disease (see Figure 4.23.1).

Terrien marginal degeneration: Usually bilateral, often asymptomatic. Slowly progressive thinning of the peripheral cornea; typically superior; more often in men. The anterior chamber is quiet, and the eye is typically not injected although may be associated with inflammatory signs and symptoms secondary to epithelial breakdown and inflammatory or infectious infiltrates. A yellow line (lipid) may appear, with a fine pannus along the central edge of the thinning. The thinning may slowly spread circumferentially. Refractive changes, including irregular and against-the-rule astigmatism are often present. The epithelium usually remains intact, but perforation may occur with minor trauma.

Mooren ulcer: Unilateral or bilateral. Painful corneal thinning and ulceration with inflammation. Initially starts as a focal area in the peripheral cornea, nasally or temporally with involvement of the limbus; later extends circumferentially or centrally. Unlike PUK, Mooren ulcer usually does not involve the sclera. An epithelial defect, stromal infiltrate/thinning, and an undermined leading edge are typically present. Limbal blood vessels may grow into the ulcer, and perforation can occur. Often idiopathic (autoimmunity may play a key role); diagnosis of exclusion after ruling out the aforementioned systemic causes of PUK. Mooren-like ulcer has been associated with systemic hepatitis C virus infection. Bilateral cases are more resistant to treatment than unilateral cases.

Pellucid marginal degeneration: Painless, noninflammatory bilateral asymmetric corneal thinning of the inferior peripheral cornea (usually from the 4- to 8-o’clock positions). There is no anterior chamber reaction, conjunctival injection, lipid deposition, or vascularization. The epithelium is intact. Corneal protrusion may be seen above the area of thinning. The thinning may slowly progress.

Furrow degeneration: Painless corneal thinning just peripheral to an arcus senilis, typically in the elderly. Noninflammatory without vascularization. Perforation is rare. Usually nonprogressive and does not require treatment.

Delle: Painless oval corneal thinning resulting from corneal drying and stromal dehydration adjacent to an abnormal conjunctival or corneal elevation. The overlying epithelium may be compromised but is often intact. See 4.24, Delle.

Staphylococcal hypersensitivity/marginal keratitis: Peripheral, white corneal infiltrate(s) with limbal clearing that may have an epithelial defect and mild thinning. See 4.19, Staphylococcal Hypersensitivity.

Dry eye syndrome: Peripheral (or central) sterile corneal melts may result from severe cases of dry eye. See 4.3, Dry Eye Syndrome.

Exposure/neurotrophic keratopathy: In severe cases, a sterile oval ulcer may develop in the inferior interpalpebral portion of the cornea without signs of significant inflammation. May be associated with an eyelid abnormality, a fifth or seventh cranial nerve defect, or proptosis. The ulcer may become superinfected. See 4.5, Exposure Keratopathy and 4.6, Neurotrophic Keratopathy.

Sclerokeratitis: Corneal ulceration may be associated with scleritis. Scleral edema with or without nodules develops, scleral vessels become engorged, and the sclera may develop a blue hue. An underlying connective tissue disease, especially GPA, must be ruled out. See 5.7, Scleritis.

Ocular rosacea: Typically affects the inferior cornea in middle-aged patients. Erythema and telangiectasia of the eyelid margins, corneal neovascularization. See 5.9, Ocular Rosacea.

Others: Cataract surgery, inflammatory bowel disease, previous HSV or VZV infections, and leukemia can rarely cause peripheral corneal thinning/ulceration.